The interplay of fatigue and depression in chronic illness is a topic that pervades much of medicine. However, the literature is rather limited when it comes to understanding the separate effects of illness severity and mood on the patient’s experience of fatigue. We wondered about the relationship among these constructs in patients with obstructive sleep apnea.

Affecting up to 9% of middle-aged adults (with higher percentages in the elderly), obstructive sleep apnea is a potentially devastating illness that involves chronic sleep loss and associated hypoxia

(1–

4).

During the night, patients with obstructive sleep apnea experience multiple episodes in which the airway collapses and breathing stops—over 100 events per hour in severe cases—resulting in repeated arousals.

Patients with obstructive sleep apnea frequently complain of both fatigue and sleepiness. Although these terms are sometimes used interchangeably and are both associated with diminished quality of life and curtailment of daytime activities, there are conceptual differences. Sleepiness, or the propensity to fall asleep, is believed to reflect a physiological need for sleep and is objectively quantifiable with a daytime test such as the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test

(5) or the Multiple Sleep Latency Test

(6). On these tests, patients with obstructive sleep apnea consistently score in the “very sleepy” range. For example, on the Multiple Sleep Latency Test, healthy adults show mean time to sleep onset of 10–20 minutes. Adults with times of 5–6 minutes are considered “very (pathologically) sleepy.” Fatigue, on the other hand, is a terribly common but poorly understood complaint in obstructive sleep apnea

(7) and many other chronic illnesses

(8–

37). Fatigue encompasses physical and psychological factors as well as social and cultural influences. The conceptual borders of fatigue are ill defined and shade into areas such as tiredness, decreased strength, lack of energy, lethargy, and difficulty with concentration. Like pain, fatigue is a symptom that is nearly always assessed by self-report. For this investigation we relied on the fatigue-inertia subscale of the Profile of Mood States (POMS), which defines fatigue as “a mood of weariness, inertia, and low energy level”

(38).

Fatigue is also a common component of mood disorders and is one of the diagnostic symptoms of major depression. There is a substantial body of research that examines the interplay of fatigue and mood in chronic illnesses. One might assume that fatigue and mood would worsen in tandem as disease severity progresses. However, findings are conflicting, even when disease severity is taken into account.

We found 31 studies that directly addressed the relationship between fatigue and depressive symptoms in illnesses such as cancer, heart disease, and rheumatological disorders. Nearly all of these studies reported a significant positive relationship between fatigue and depression

(8–

12,

14–

22,

24–

33,

35,

37,

39). One-third found significant relationships between fatigue and illness severity

(11,

13,

15,

17,

19,

23,

30,

32,

34,

39), whereas several did not

(21,

23,

25,

31,

33,

35,

36). Only three studies reported a significant association between depression and illness severity

(13,

23,

39). Four studies reported that the fatigue-depressive symptom relationship remained significant after illness severity was controlled

(10,

17,

22,

26).

Most studies of the relationship between fatigue and depressive symptoms in patients with obstructive sleep apnea focus on the change in mood symptoms after treatment. While several authors have reported improvement in both fatigue and depressive symptoms

(39,

40), findings are less clear when a placebo-controlled design is employed

(40).

In summary, while the bulk of the evidence suggests that fatigue and depressive symptoms are positively associated, there are relatively few studies that have examined the relationship between fatigue and depressive symptoms after having controlled for disease severity. Therefore, it is difficult to tease out the separate effects of physical illness and mood on the experience of fatigue. Some of the disparity in findings may be due, in part, to the variety of fatigue and depression measures used. Additional reasons for discrepancies include the fact that most studies did not control for illness severity variables and because relationships between fatigue and depressive symptoms may vary depending on the illness being studied.

We hypothesized that depressive symptoms would account for a significant portion of the fatigue experienced by patients with obstructive sleep apnea—beyond that explained by sleep disruption and hypoxia. Much of the previous research into mood and sleep disturbance has focused on patients with diagnosed affective disorders. However, there is a growing interest in the quality of life impact of depressive symptoms that fall below the threshold of a diagnosable disorder. For this reason, we looked at the relationship between depressive symptoms and fatigue by using a continuous measure of depressive symptoms in a nonpsychiatric group of patients with obstructive sleep apnea.

Method

Sixty patients with obstructive sleep apnea were recruited by advertising and word of mouth to participate in our research on sympathetic nervous system physiology in obstructive sleep apnea. To qualify, participants had to be 100%–150% of ideal body weight per Metropolitan Life Insurance tables

(41). Although obstructive sleep apnea is more common among the obese, participants >150% of ideal body weight were excluded because of the possibility of confounding by other conditions associated with obesity. Potential participants were also excluded if they had major medical illnesses other than obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension. The protocol was approved by the University of California, San Diego, Human Subjects Committee. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Participants had their sleep monitored for an entire night in the General Clinical Research Center with a standard regimen of polysomnography: central and occipital EEG, bilateral electro-oculogram, submental and bilateral tibialis electromyogram, nasal/oral airflow (using a thermistor), and thoracic and abdominal excursions with Respitrace respiratory inductive plethysmography. Oxygen saturation was monitored by using a pulse oximeter (Biox 3740, Datex-Ohmeda, Louisville, Colo.) and was analyzed by using computer software (Profox Associates, Inc., Escondido, Calif.). The oxygen saturation variable selected as indicative of obstructive sleep apnea severity was percent of time that oxygen saturation was <90%.

Sleep recordings were scored according to the criteria of Rechtschaffen and Kales

(42). Apneas were defined as decrements in airflow of ≥90% from baseline for ≥10 seconds. Hypopneas were defined as decrements in airflow of ≥50% but <90% from baseline for ≥10 seconds

(43). The majority of subjects had solely obstructive type events; only a few subjects showed evidence of central apneas. Potential participants who showed predominant central apneas (>50% of total apneas) were excluded. The number of apneas and hypopneas per hour were calculated to obtain the respiratory disturbance index. Obstructive sleep apnea was defined as a score on the respiratory disturbance index ≥15.

Participants completed the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D Scale)

(44), the POMS

(38), and Medical Outcomes Study surveys

(45). The CES-D Scale is a frequently used 20-item self-report scale that has been shown to be reliable and valid for assessing depressive symptoms

(44). In a variety of populations, a large percentage of subjects with a score ≥16 have been shown to meet diagnostic criteria for dysthymia or major depression

(46,

47). When used with medically ill patients, depression rating scales are sometimes influenced by illness symptoms. For example, mood-related observations in patients with obstructive sleep apnea could be confounded by fatigue or sleepiness. However, the CES-D Scale primarily taps cognitive/affective aspects of depression and has been shown to be useful in chronically ill groups experiencing fatigue (e.g., HIV, cancer)

(48,

49), including obstructive sleep apnea patients

(50,

51).

The POMS is a well-established, factor-analytically derived measure of psychological distress for which high levels of reliability and validity have been documented

(38). The POMS consists of 65 adjectives rated on a 0–4 scale that can be consolidated into six subscales: fatigue-inertia, depression-dejection, vigor-activity, tension-anxiety, anger-hostility, and confusion-bewilderment. The POMS has been used in a variety of chronically ill and well populations

(38,

52–

58), including obstructive sleep apnea patients

(40,

59,

60). We were particularly interested in the fatigue-inertia subscale. This subscale measures weariness, inertia, and low energy level—states commonly experienced by patients with obstructive sleep apnea—and has been validated as a separate factor in several studies. Norms have been published for a variety of patient and nonpatient groups

(38).

Data were analyzed by using SPSS 10.0 software (1999) hierarchical linear regression with POMS fatigue subscale score as the dependent variable: step 1, forced entry of obstructive sleep apnea severity variables (score on the respiratory disturbance index, the percent of time oxygen saturation was <90% ); step 2, forced entry of CES-D Scale score. Because depression and fatigue overlap, the analysis was rerun after excluding three fatigue-related CES-D Scale items (item 7: “…everything I did was an effort”; item 11: “…sleep was restless”; and item 20: “…could not get going)

(44). Findings were similar, so results using the full CES-D Scale are reported.

We also analyzed the data by using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) approach. A cutoff score of 16 on the CES-D was used to dichotomize the patient group into those with high (i.e., ≥16) versus low (i.e., <16) scores. In addition, we used median values to split the patient group into high versus low respiratory disturbance index (median=40) groups and high versus low percent of time oxygen saturation was <90% (median=10%) groups. ANCOVA was then conducted to see if the high versus low groups for CES-D Scale score, respiratory disturbance index, and oxygen saturation differed in terms of POMS fatigue subscale score. All tests were two-tailed. We also reran the analyses substituting the energy/fatigue subscale of the Medical Outcomes Study surveys

(45) for the POMS fatigue subscale and the POMS depression subscale for the CES-D Scale.

Results

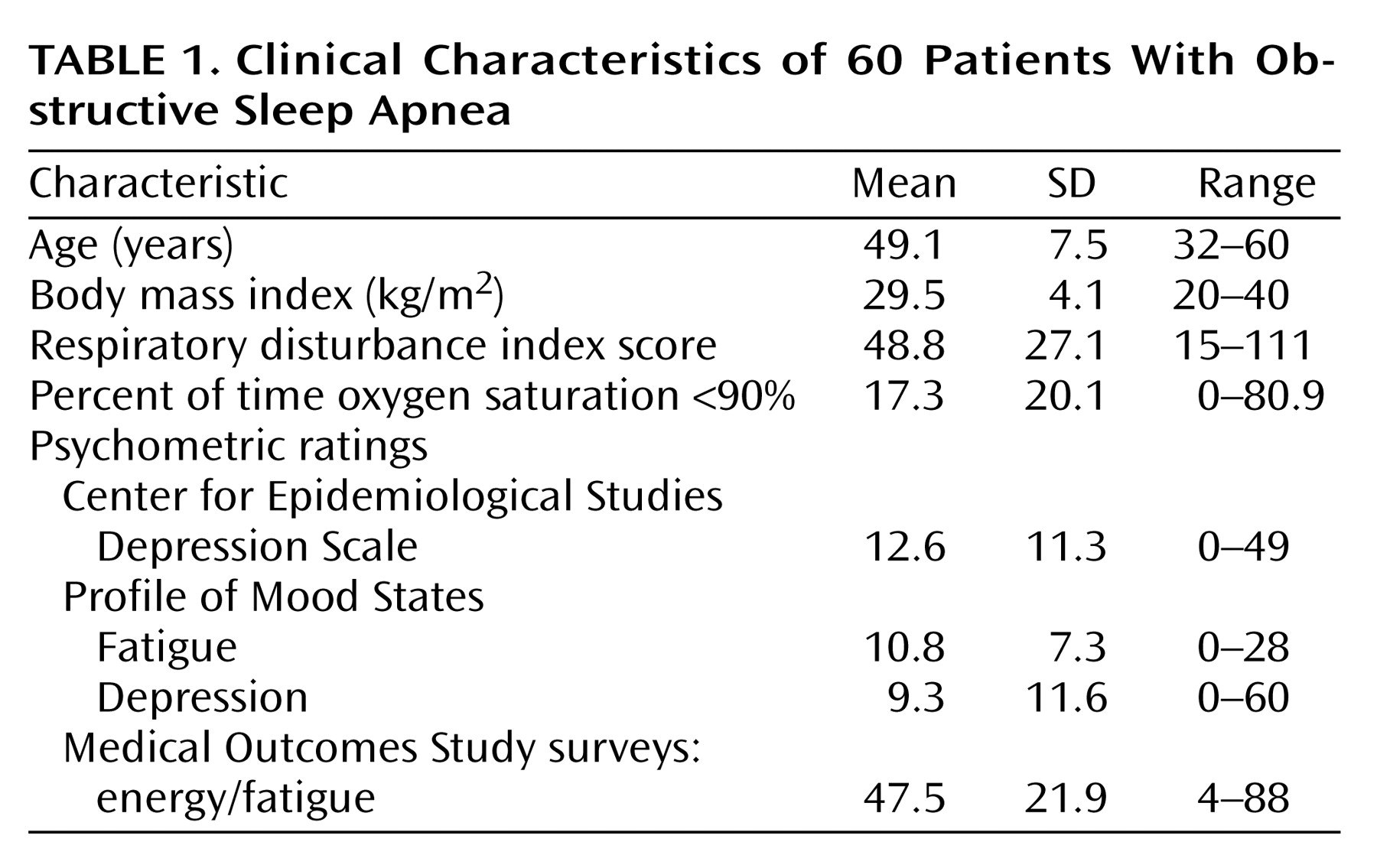

Subjects included 51 men and nine women (five African American, one Asian, 40 Caucasian, 12 Hispanic, two “other” ethnicities) whose average age was 49.1 years. Other clinical characteristics of the patient group are presented in

Table 1. One-third of the subjects had a CES-D Scale score ≥16.

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for POMS fatigue subscale score versus obstructive sleep apnea severity variables and CES-D Scale score. Score on the respiratory disturbance index (r=0.11, df=58, p<0.42) and the percent of time oxygen saturation was <90% (r=0.20, df=58, p=0.12) were not significantly correlated with POMS fatigue subscale scores, but CES-D Scale score was (r=0.68, df=58, p<0.001).

We analyzed these data by using multiple statistical approaches to ascertain how robust these findings are. Specifically, we examined the additive effect of depressive symptoms on fatigue after we controlled for obstructive sleep apnea severity by using both multiple regression and ANCOVA. We also tested the models by using different fatigue and depressive symptom measures. As the following paragraphs make clear, the findings are substantially the same—depressive symptoms far outweigh obstructive sleep apnea severity in accounting for fatigue.

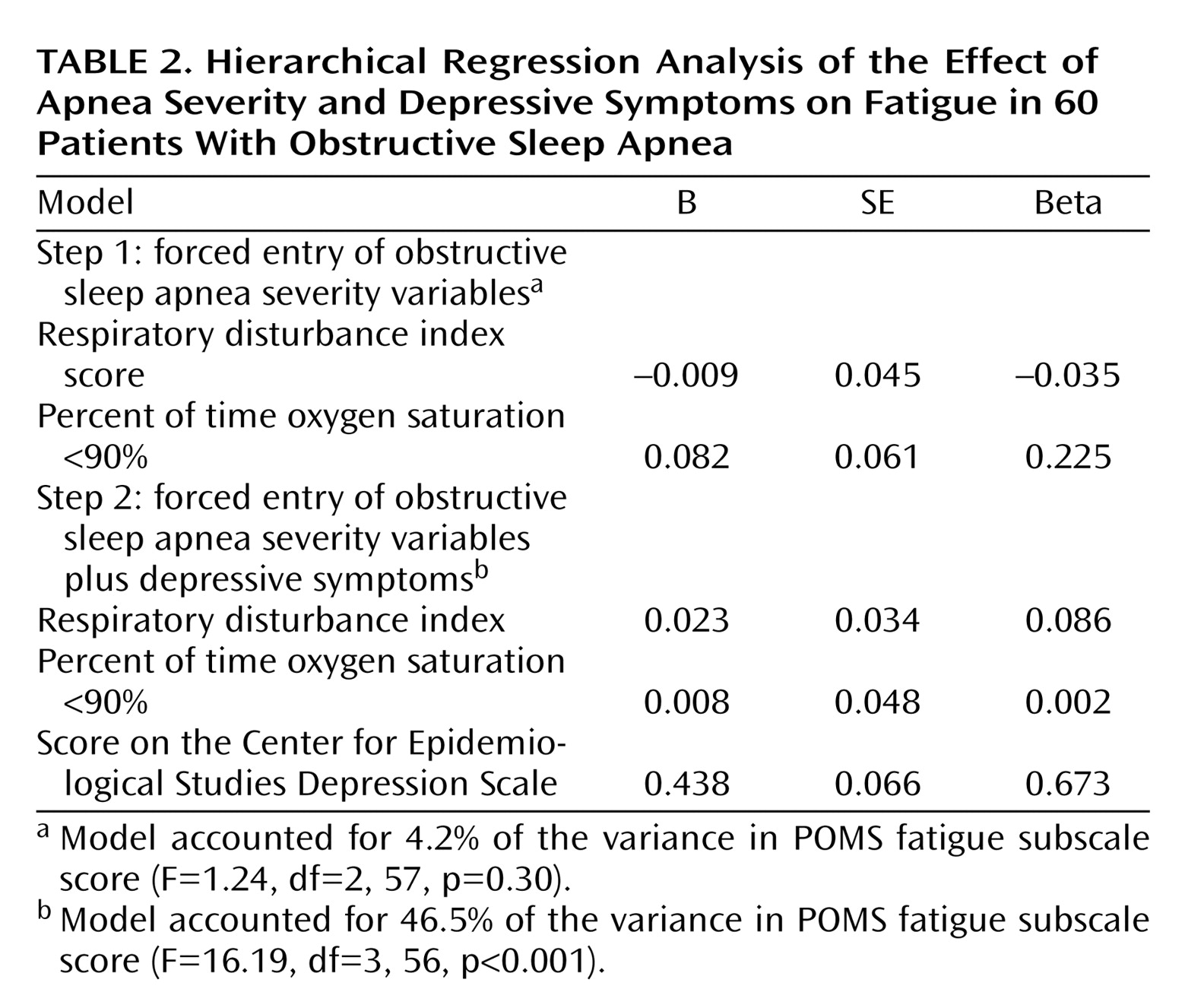

Results of the hierarchical linear regression analysis were significant (

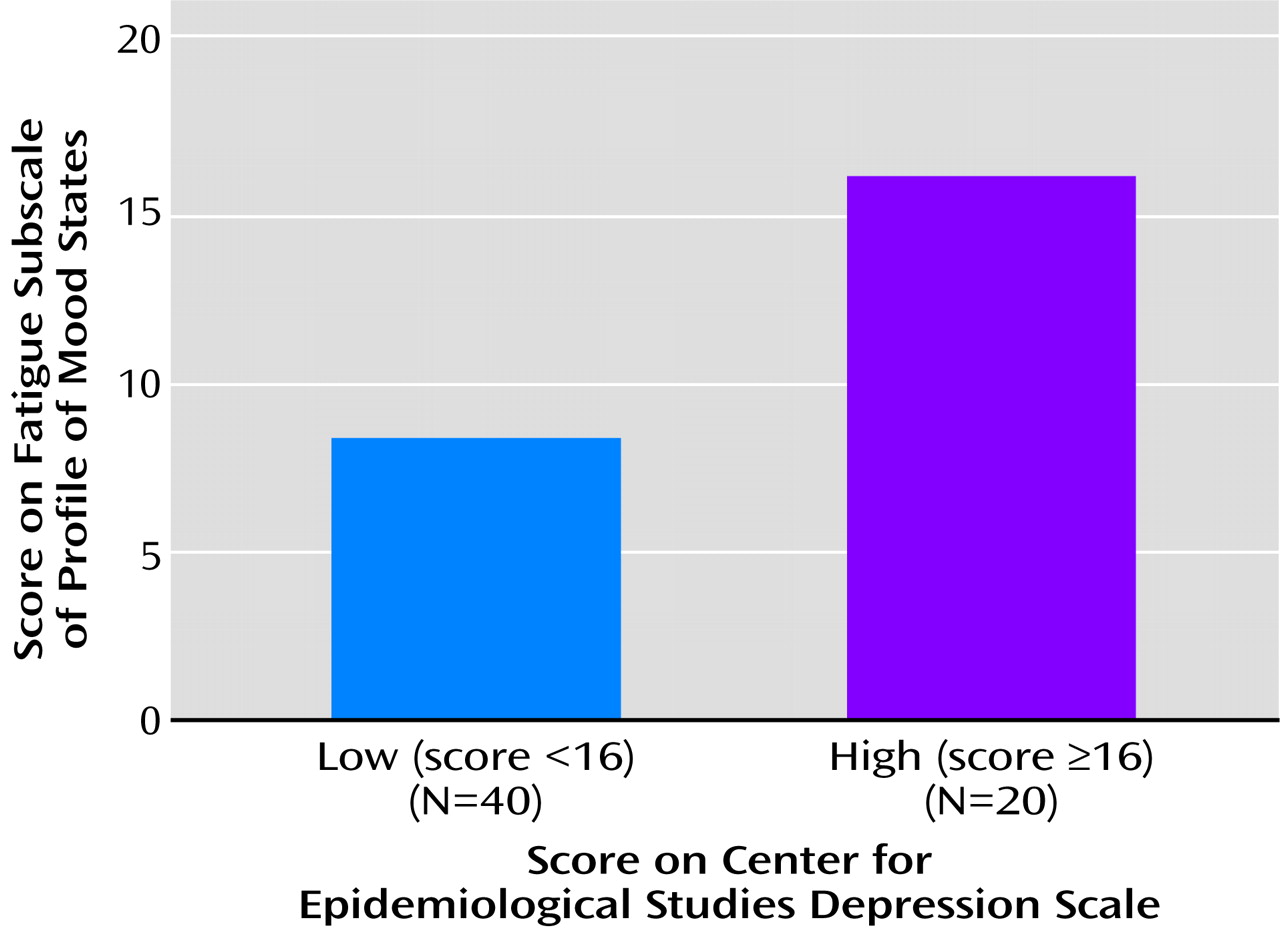

Table 2). While score on the respiratory disturbance index and the percent of time oxygen saturation was <90% together accounted for 4.2% of the variance in POMS fatigue subscale score, the CES-D Scale score accounted for an additional 42.3%. In the ANCOVA, after the apnea severity variables were controlled, significantly more fatigue was seen in patients in the high CES-D Scale score group (mean=16.2, SD=6.4) than in the low CES-D Scale score group (mean=8.4, SD=6.3) (

Figure 1). Analyses of variance that compared the high versus low groups for either respiratory disturbance index score or the percent of time oxygen saturation was <90% were not significant in predicting POMS fatigue subscale scores.

We reran the hierarchical model using the POMS depression subscale in place of the CES-D and the energy/fatigue subscale from the Medical Outcomes Study surveys in place of the POMS fatigue subscale. Results remained essentially the same.

Discussion

Whether a result of chronic medical illness or disturbance of mood, fatigue can have a devastating impact on quality of life. The sleep literature cites fatigue as a common sequela of obstructive sleep apnea. In obstructive sleep apnea patients with depressive symptoms, it has been unclear to what degree the obstructive sleep apnea severity and mood disturbance contribute to the fatigue experienced. We hypothesized that depressive symptoms would account for a significant amount of the fatigue reported in obstructive sleep apnea patients after apnea severity was controlled. Our findings strongly support this hypothesis.

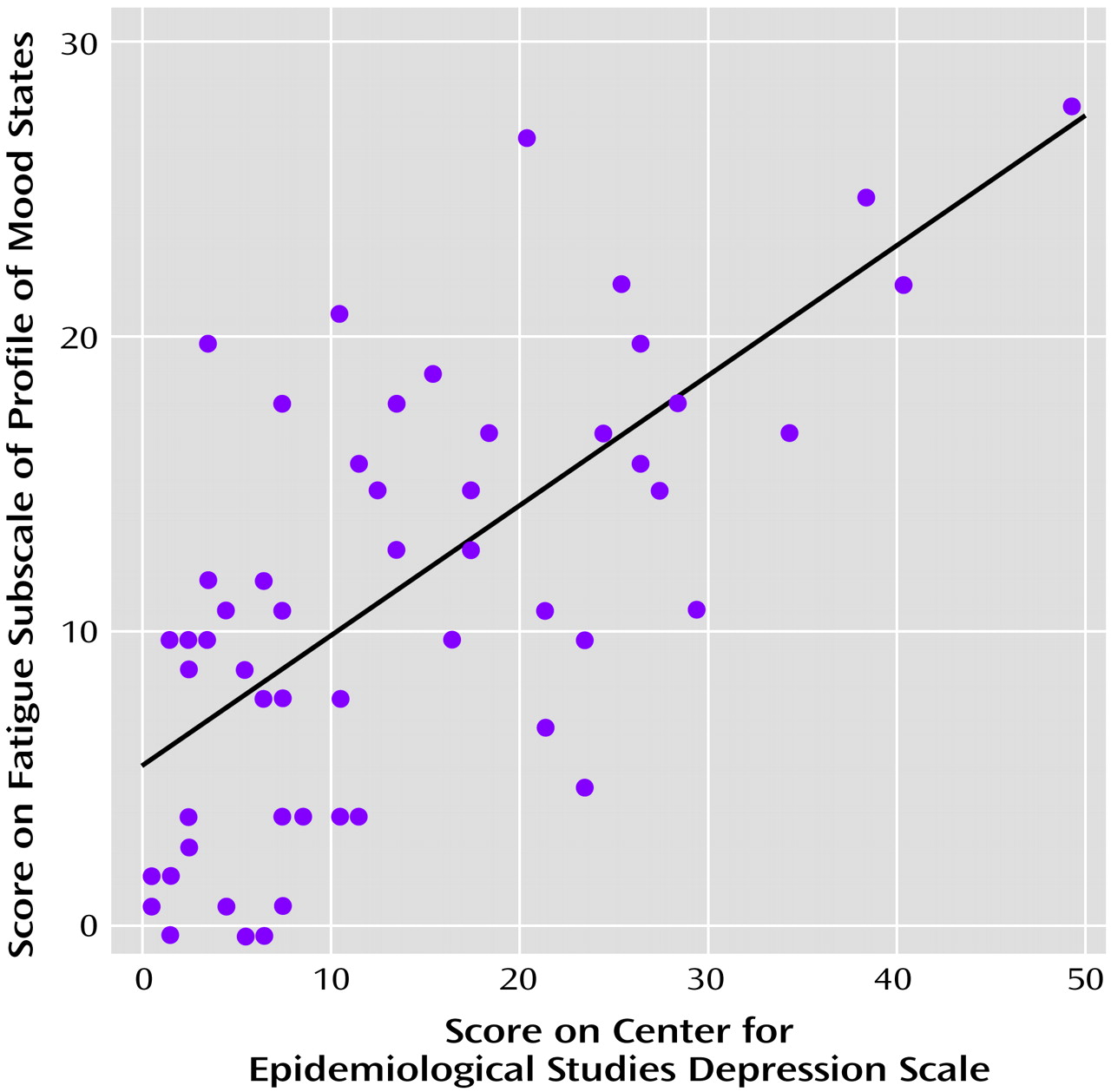

Simple correlations revealed that depressive symptoms, but not obstructive sleep apnea severity, were significantly associated with self-reported fatigue. However, we took a conservative approach and included the obstructive sleep apnea severity variables in the analyses before testing the relationship between the CES-D Scale and POMS fatigue subscale scores. Results revealed that depressive symptoms accounted for 10 times the amount of variance in fatigue in obstructive sleep apnea patients as did apnea severity (as measured by respiratory disturbance index score and the percent of time oxygen saturation was <90%). To determine if these relationships were consistent across the spectrum of depressive symptoms, we plotted CES-D Scale scores against POMS fatigue, revealing a fairly steady positive dose-response relationship for depressive symptoms (

Figure 2). Furthermore, after controlling for obstructive sleep apnea severity, patients likely to have a mood disorder (CES-D Scale score ≥16) reported twice as much fatigue as patients reporting fewer depressive symptoms (

Figure 1). These relationships proved to be remarkably robust—the same pattern of findings emerged when substituting other measures of fatigue and depressive symptoms. Results held even after eliminating fatigue-related items on the CES-D Scale, so they cannot be explained by symptom overlap.

Limitations

Our subject population came primarily from advertisements and may not be representative of the type of patients seen in the sleep disorders clinic. Nevertheless, the severity of obstructive sleep apnea was equivalent to that seen in the clinic. The ethnic distribution of our patient group was representative of the population in San Diego County. However, because data on ethnicity in obstructive sleep apnea are limited, we cannot be certain that our patient group reflects the ethnic distribution of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population.

We relied on subject self-reports to gauge fatigue and depressive symptoms, and such instruments are often influenced by response bias. However, we reran the analyses after controlling for scores on the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale, a common measure of response bias

(61). The Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale did not contribute significantly to the regression or ANCOVA models (p=0.833 and p=0.283, respectively), and interpretation of findings did not change when it was included.

Because our design was cross-sectional, we cannot determine direction of causality between depressive symptoms and fatigue. It is possible that fatigue causes depressive symptoms. However, obstructive sleep apnea severity was not directly related to fatigue. Therefore, if fatigue causes depression, our findings suggest it would be the result of factors other than obstructive sleep apnea severity.

While we relied on the CES-D Scale, the structured clinical interview is the gold standard for assessing depressive symptoms. However, we were less interested in determining the presence of a diagnosable mood disorder than in assessing the mood-fatigue relationship across a spectrum of depressive symptoms. The CES-D Scale is one of the more reliable and valid instruments for this purpose. Findings were essentially the same when substituting the POMS depression scale.

Conclusions

These results suggest that it is depressive symptoms rather than respiratory disturbance or oxygen saturation levels that account for the fatigue experienced by patients with obstructive sleep apnea. This mood-fatigue relationship is consistent across a wide range of depressive symptoms. We conclude that depressive symptoms must be considered in studies of fatigue in obstructive sleep apnea. From a clinical perspective, the assessment and treatment of mood disorders—not just the disordered breathing itself—might have major potential to reduce the fatigue experienced in obstructive sleep apnea. These findings also demonstrate the importance of considering subthreshold levels of depressive symptoms in patients living with chronic illness.