There is limited information available about the attributes of older adults with serious and persistent psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and chronic depression

(1). There are only a few studies that have focused on the prediction of dwelling status in older schizophrenic patients with regard to symptoms and cognitive status

(2,

3).

We hypothesized that patients within the schizophrenia spectrum disorder who were living in a supervised setting would demonstrate more severe symptoms and greater cognitive impairment than those living independently. While these hypotheses would seem intuitively obvious, the study also attempted to compare the relative impact of these variables by examining the magnitude of their effect sizes.

Method

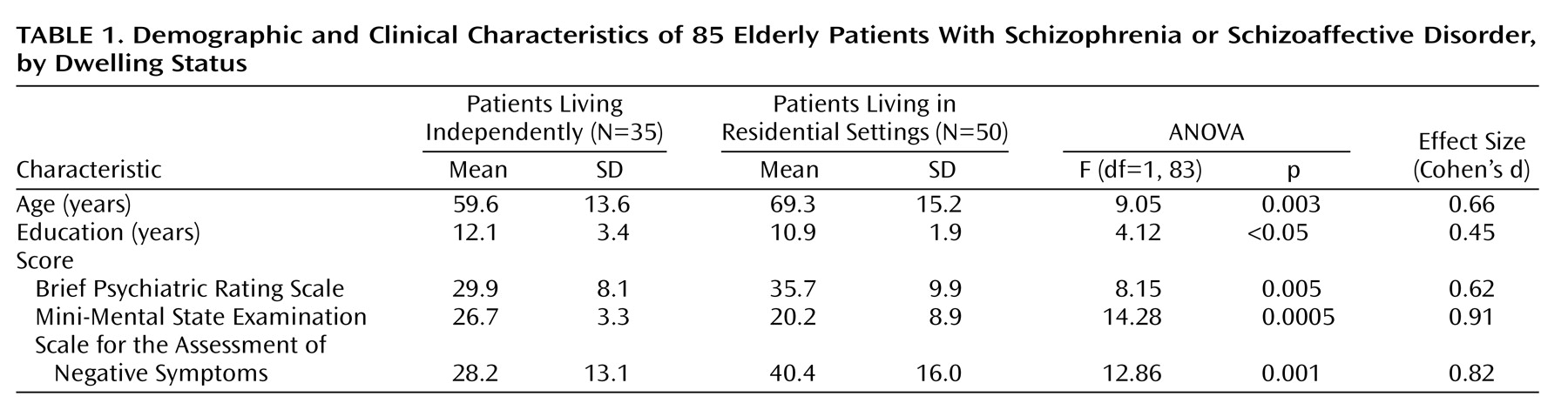

This study is part of a consortium for research on older people with schizophrenia, a multisite effort to study older patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. The study group consisted of 85 patients (29 men and 56 women) with a medical chart diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were residing in group homes, family-care homes, nursing homes, and independent living settings. These patients were followed in a continuing day-treatment program, an outpatient clinic, or in a skilled nursing facility. The patients with mental retardation, severe head injury, or seizure disorder were excluded. The subjects were at least 55 years of age (mean=65.3, SD=15.2). A total of 38.8% were single, 23.5% were widowed, 24.7% were divorced, 8.2% were married, and 4.7% were separated. Their mean educational level was 11.39 years (SD=2.69); the majority were disabled (77.6%). The mean age at onset of illness was 30.3 years (SD=14.2). The prevalence of alcohol (4.9%) and drug (4.7%) abuse was low.

The institutional review board of Olean General Hospital approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the subjects or the authorized representatives of those who lacked capacity. The patients were dichotomized into two groups on the basis of dwelling status: those who were living independently and those who were living in residential settings (group homes, family-care homes, or nursing homes). Group homes are run by a state-certified agency for patients with chronic mental illness. Family-care homes are privately owned and provide meals, lodging, and medication supervision for patients. The state pays the family (like a surrogate family) to look after individuals with chronic mental illness.

The two groups were compared with regard to scores on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

(4), the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)

(5), the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)

(6), the Geriatric Depression Scale

(7) (administered by the same trained rater), level of education in years, and age. Statistical analysis was conducted by using SPSS (SPSS, Chicago). The data were analyzed with a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) by using dwelling status as the independent variable. The magnitude of the effects was quantified by Cohen’s d

(8,

9).

Discussion

The differences between the two groups in scores for negative symptoms and on the MMSE were prominently demonstrated by a robust effect size. Auslander et al.

(3) used a younger cohort of patients, with a mean age of 55, who were predominantly male (64.4%) and mostly veterans, while ours was a community group, was older (with a mean age 65 years), and was composed of 65.9% women. The patients with prominent negative symptoms or a low cognitive level performed poorly with regard to their activities of daily living as well as the instrumental activities of daily living, resulting in the need for supervision.

In this study, the mean MMSE scores were 27 and 20 for those living independently and for those living in a supervised setting, respectively. This was consistent with our a priori hypothesis. The MMSE score is a relatively crude measure of cognition compared to the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale

(10), which was used by Auslander et al.

(3); both studies revealing consistent findings with regard to cognition. MMSE scores may be used to help in the discharge planning of hospitalized patients with regard to living arrangements. There was a 6-point difference between the two groups in our study, with a mean BPRS score of 30 for those living independently and 36 in those in supervised living. Individuals with a higher level of positive symptoms were less likely to live independently. The educational status of the subjects was also a correlate of the dwelling status in this study. Those living independently had an average of 12.1 years of education, while those living in a supervised setting had an average of 10.9 years of education.

These data reveal that MMSE scores and levels of negative symptoms may be used to determine the nature of the dwelling the patient should have after hospital discharge. Future research should attempt to articulate the ranges of cognitive function that are compatible with different residential placements.