Limitations and Strengths

Data in Danish registers are collected systematically and uniformly and without the purpose of being used for specific research. Use of such data may reduce the risk of differential misclassification bias. On the other hand, the selection of variables that can be included in the analysis is largely dependent on the availability of data in source registers, making some variables of interest, e.g., previous suicide attempts, absent in this study. Also, information on psychiatric illness not leading to hospitalization was not included in the register before the year 1995, which might result in an underestimate of mental illness in the analyses presented here. Nevertheless, because this study used data retrieved from Danish longitudinal registers, it is, to our knowledge, the largest case-control study in suicide research in terms of both the number of suicides and the number of variables included in the analysis. The large number of suicides yielded good statistical power for the study of relatively uncommon risk factors, and the large number of variables allowed estimation of the relative importance of a range of factors associated with suicide.

Findings and Explanations

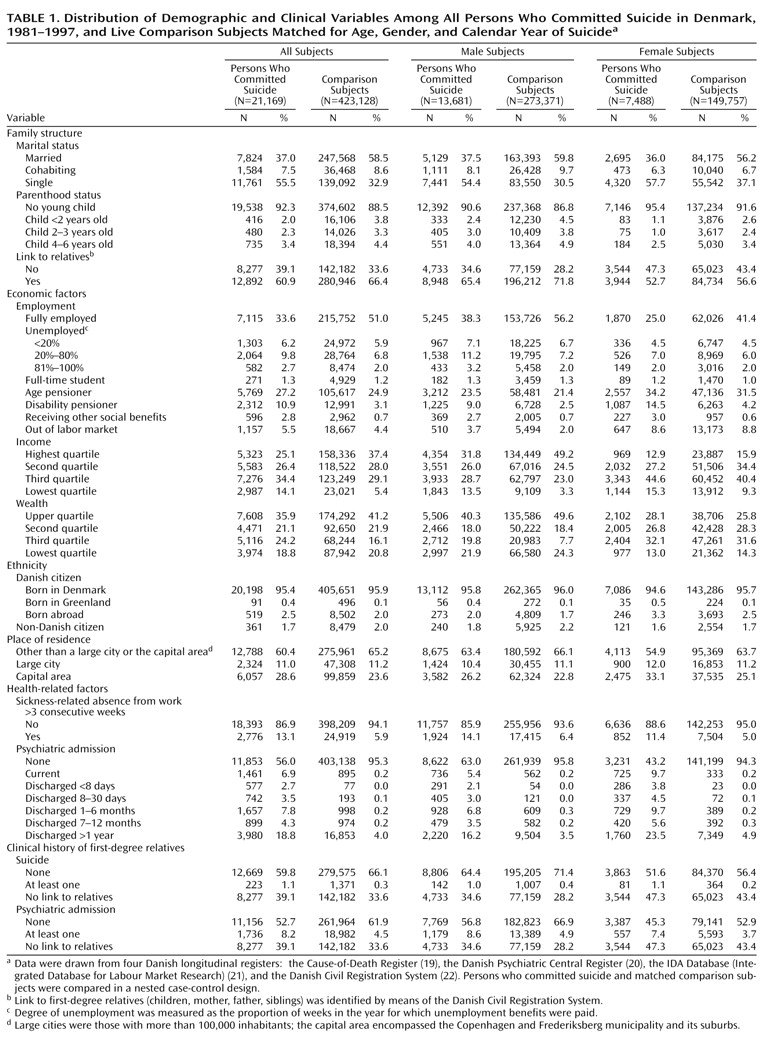

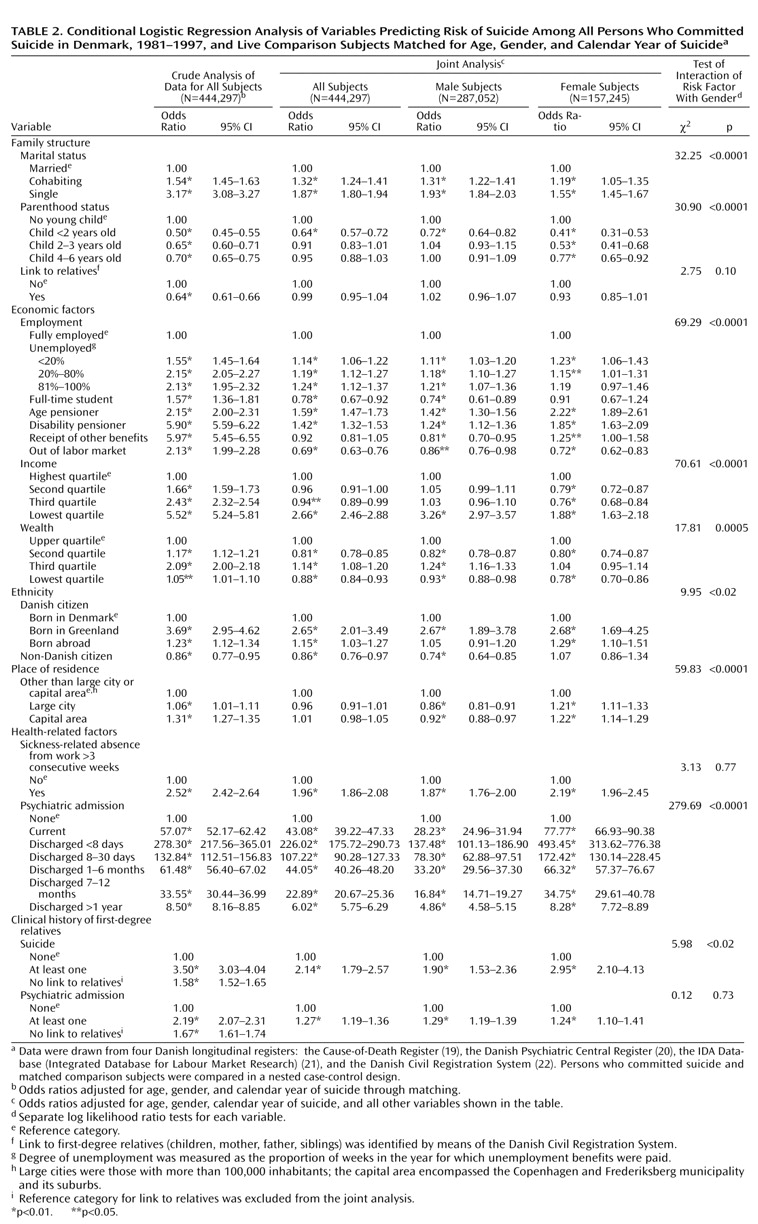

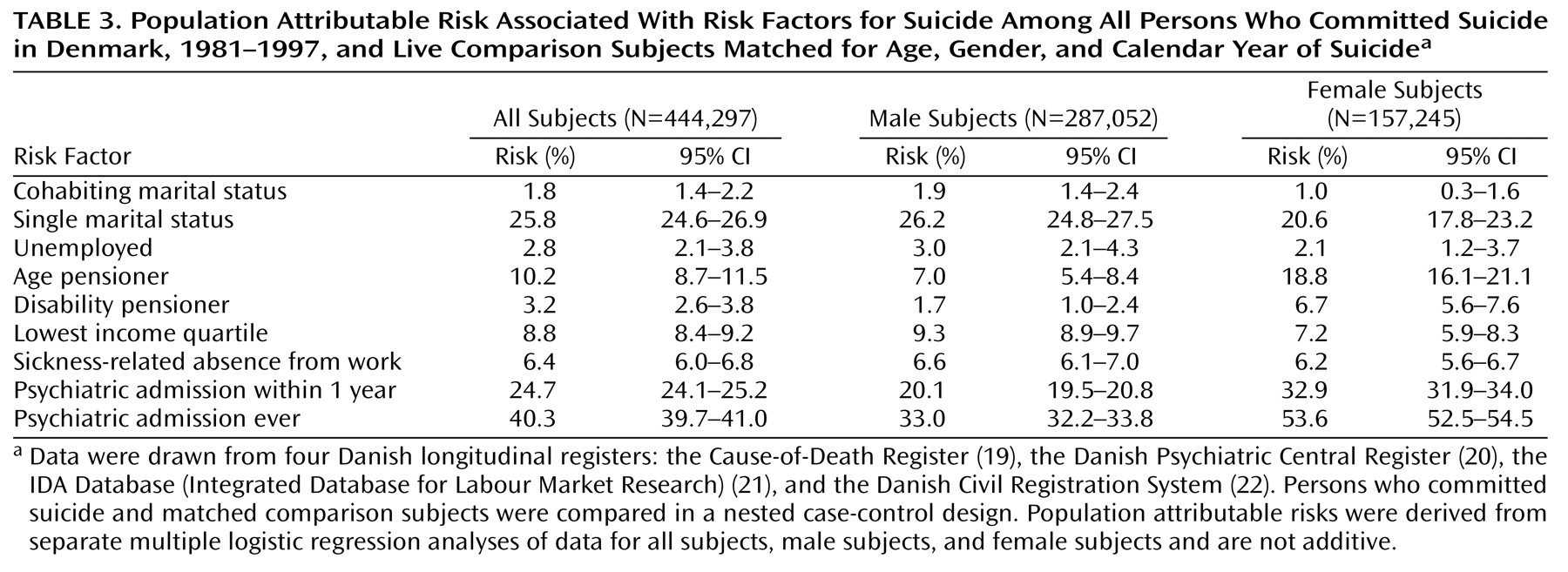

This study demonstrates that a history of hospitalization for psychiatric disorder was the strongest risk factor for suicide in terms of both effect size and attributable risk in the general population in Denmark and that this risk factor increased suicide risk significantly more in female than in male subjects. These findings are highly consistent with our previous reports

(11,

12) and also in line with the literature

(9,

27,

28), although our estimates of suicide risk are likely to be low. Also, the finding of a high risk of suicide for people with disability or a sickness-related absence from work is concordant with other reports

(6,

8). The obvious decrease in the odds ratios associated with disability and sickness-related absence from work in the joint analysis, compared with the crude analysis, might be explained by the strong association between these two variables and mental illness.

The findings regarding the effect of labor market status, income, and wealth on suicide (with adjustment only for age and gender) are compatible with other reports

(4,

5). However, the fact that the odds ratios for these variables decreased markedly or even reversed with further adjustment for other factors suggests that the effects of socioeconomic factors on suicide tend to be overestimated when the distribution of psychiatric disorders is not taken into account. Our results showing that economic stressors such as unemployment and low income increase suicide risk more in male than in female subjects are in line with the results of our previous study

(12) and support the hypothesis that men respond more strongly to poor economic conditions than women do

(29).

As for family structure, previous studies have reported that single people are more likely to commit suicide

(2,

3), but our study further shows a significantly higher risk of suicide for cohabiting people even though cohabitation is almost equivalent to an officially certified marriage relationship in the eyes of most people in Denmark. Moreover, consistent with a few studies reporting that same-gender sexual orientation is associated with suicidality

(30,

31), our results clearly show an elevated suicide risk for homosexuals, although this effect was likely to be underestimated because data were available only for those choosing to officially register as partners and only for the period after 1994. Taken together, our results suggest that a traditional family structure may be associated with lower suicide risk, although we cannot determine if the lower risk results from a protective effect of marriage, e.g., in the face of setbacks or difficulties, or from a marriage selection effect

(32). In addition, our findings of gender differences in relation to the effects of marital status and parenthood on suicide risk support the hypothesis first suggested by Durkheim

(17) that the protective effect of marriage for women is largely an effect of being a parent. This hypothesis is also concordant with the so-called attachment effect suggested by Adam

(16). In our study, being a parent of a young child, rather than being married per se, appeared to explain the apparent protective effect of marriage for women, whereas marriage appeared to be a protective factor in its own right for men

(33).

With regard to demographic factors, this study shows that living in urban areas, in the context of other factors, increased suicide risk in female subjects but reduced the risk in male subjects. This difference might be explained by aspects of living in a big city that affect men and women differently, e.g., better job opportunities may be more likely to benefit men, whereas women may be more vulnerable in a competitive environment than their male counterparts. The high risk of suicide for Danish citizens born in Greenland may be explained by the Greenlandic cultural tradition of seeing suicide as an acceptable solution for problems rather than as a mortal sin

(34). The finding of a high risk of suicide for foreign-born Danes is consistent with a Swedish study by Johansson et al.

(6), but this effect was prominent only for female subjects, after other factors were adjusted. Meanwhile, this study showed that male non-Danish citizens had a lower risk of suicide, perhaps due to racial differences in suicide risk

(35) and/or cultural differences in attitudes toward suicidal behavior. Denmark has relatively few immigrants, with female immigrants often coming from Western European and other Nordic countries where suicide rates in women are generally high, and male immigrants, especially those with a non-Danish citizenship, coming from a broader spectrum of countries. The fact that a relatively large proportion of male immigrants come from Islamic countries where suicide rates traditionally are low may also contribute to our findings. Another explanation may be that female immigrants to Denmark often come for the purpose of marriage rather than work or business, and thus they may have fewer contacts with other people, may be more isolated from the society, may be less independent, and may experience more stressors, compared to male immigrants.

The familial clustering of suicidal behaviors and psychiatric disorders has been demonstrated in studies of both adolescent and adult suicide victims and attempters

(14,

36,

37). Our study further shows that the two familial factors raise the risk of suicide even after the effects of the person’s own psychiatric admission status and other factors are adjusted, although this finding may apply only to relatively young subjects because older people in this study rarely had registered links to their relatives. Since people with a psychiatric disorder are more likely to commit suicide

(28), one could argue that liability for suicidal behavior is familially transmitted as a trait dependent on psychiatric disorder. However, our findings suggest that it is less likely that family clustering of suicidal behavior is due only to familial transmission of mental illness. We address this issue elsewhere

(38). In addition, the slightly stronger influence of family suicide history in women might be explained by gender differences in reactions toward bereavement

(39).

Research and Clinical Implications

The socioeconomic environment in Denmark is similar to that in other Scandinavian countries and would probably also be comparable to that in most Western European countries. However, it may be difficult to generalize the findings of this study to other countries with different social, economic, or cultural conditions. Nevertheless, this large record linkage study has demonstrated the joint effect of a wide range of factors on suicide risk. The results suggest several factors that may be targeted in suicide prevention programs; at the same time they suggest that the effects may differ in various segments of population, e.g., by gender.

We believe, as also suggested by others

(11,

40), that mental illness should be a focus for preventive interventions and assessment of these interventions. General strategies with the potential of reducing suicide rates include providing psychiatric professionals and general practitioners with better training in the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders, as well as continuing psychiatric patients’ care beyond the point of clinical recovery. Also, broader approaches such as reducing unemployment and improving social cohesion might have some, although probably limited, effect on suicide rates.