Antipsychotic medications are effective for preventing relapse in patients with schizophrenia who have recovered from psychotic episodes

(1). This important effect has led to the recommendation that antipsychotic medications be continued indefinitely for patients who have had multiple episodes of schizophrenia. However, long-term therapy with antipsychotics may also be associated with a range of side effects, including acute extrapyramidal side effects, tardive dyskinesia, weight gain, and sedation. These side effects can interfere with long-term adherence to maintenance drug therapy and may have direct effects on adjustment to community life

(2).

The introduction of second-generation antipsychotics has led to a reevaluation of the risks and benefits of these drugs compared with older drugs for long-term maintenance therapy. There are indications that second-generation agents are at least as effective as first-generation antipsychotics in maintenance therapy. Csernansky et al.

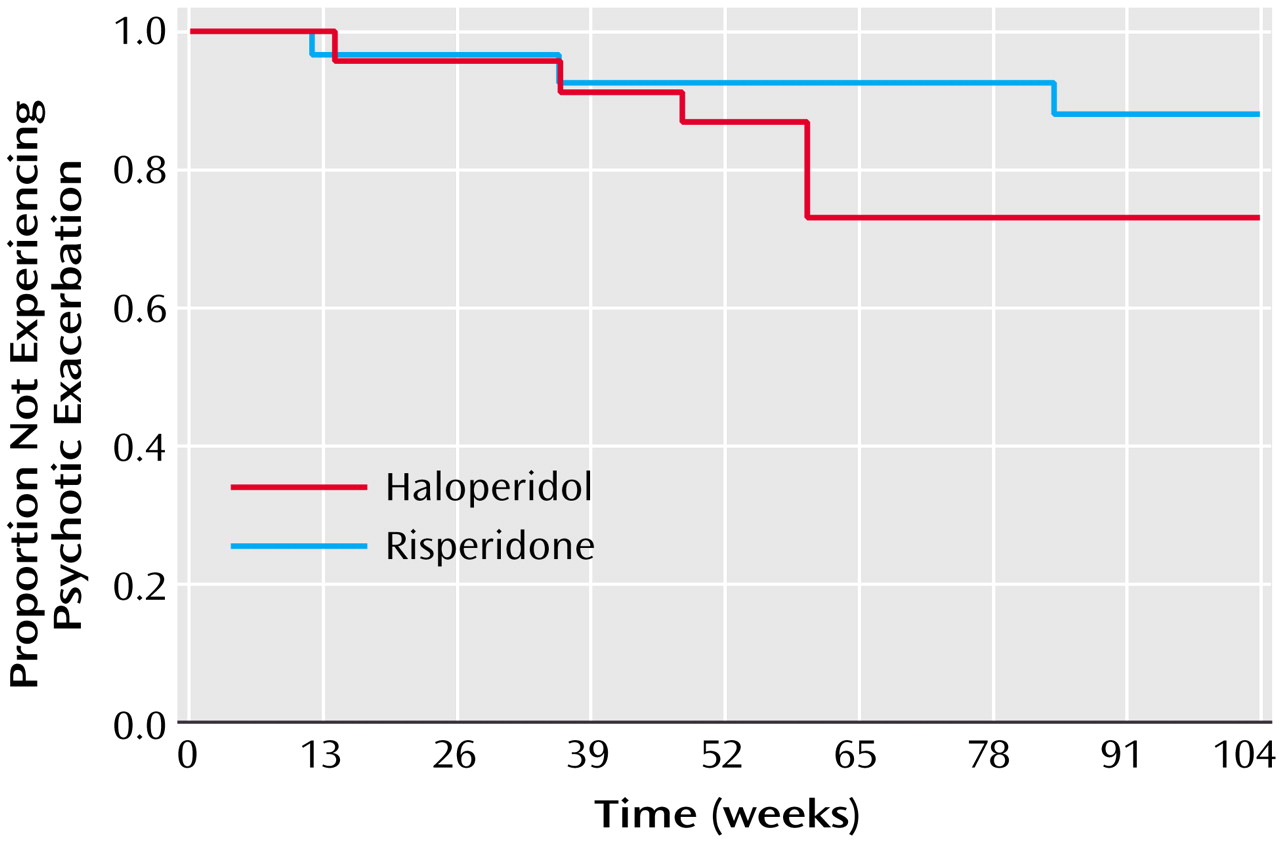

(3) randomly assigned stable outpatients to flexible doses of haloperidol or risperidone. Relapse rates computed by Kaplan-Meier estimates were 60% for haloperidol and 34% for risperidone (p<0.001). Patients who received risperidone also demonstrated greater reductions in psychotic symptoms and extrapyramidal side effects. In this study, the mean dose of haloperidol was 11.7 mg/day (SD=5.0) (compared with mean=4.9 mg/day, SD=1.9, for risperidone). This relatively high dose of haloperidol may be a limitation of this study. In a meta-analysis of studies comparing first- and second-generation antipsychotics, Geddes and coworkers

(4) reported that higher doses of haloperidol may give an advantage to the second-generation drug. In their report, when the dose of haloperidol was greater than 12 mg/day, there was an advantage to the second-generation antipsychotic, but there was no advantage below this dose. Studies that are long-term extensions of acute studies differ from true maintenance studies in that subjects are only entered into the maintenance phase when they are identified as responders to an acute trial. Nevertheless, long-term extension studies with olanzapine

(5) have provided some evidence that this second-generation drug is effective in preventing psychotic relapse. Uncontrolled studies with risperidone have also supported its effectiveness in long-term maintenance

(6). All of these studies have also demonstrated that second-generation agents are associated with fewer extrapyramidal side effects than conventional agents but varying amounts of weight gain, orthostatic hypotension, and hyperprolactinemia.

Method

Study Subjects

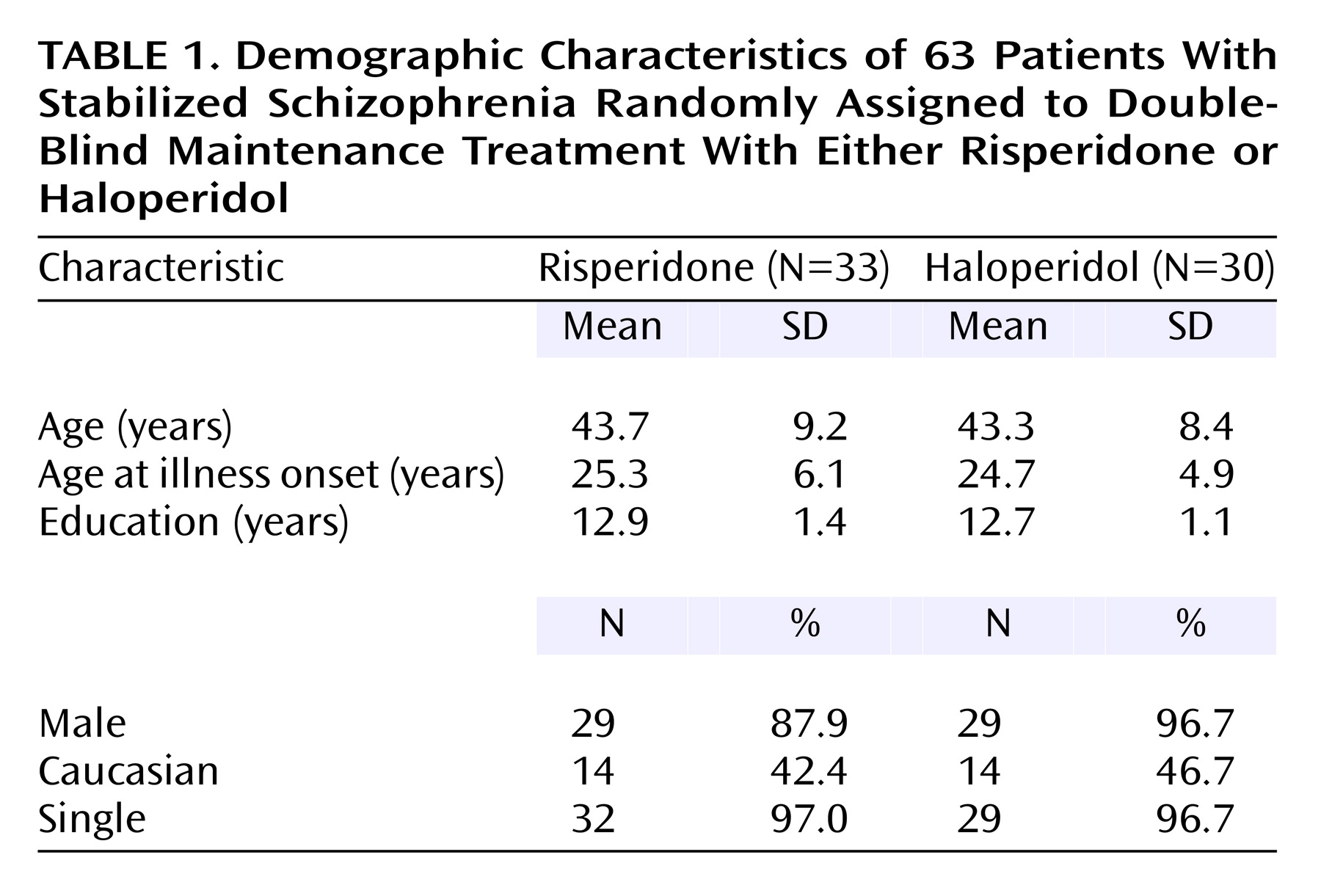

Subjects were 63 patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia according to DSM-IV criteria. The clinical diagnosis by a research psychiatrist was verified with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Psychotic Disorders. All subjects were 18–60 years of age; had at least two documented episodes of acute schizophrenic illness or at least 2 years of continuing psychotic symptoms; had been outpatients for at least 1 month; and were considered candidates for maintenance therapy with an antipsychotic. Subjects were outpatients from the West Los Angeles Health Care Center of the Veterans Administration (VA) Greater Los Angeles Health Care System, the VA Long Beach Medical Center, or the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Hospital.

Prior to study participation, all subjects provided written informed consent. Competence to give consent was assessed by using a previously described method for confirming that subjects understood the most important elements of the study

(8).

Pretreatment Stabilization Period

After patients agreed to participate in the study and gave informed consent, they entered a 2-month pretreatment stabilization period. During this time, subjects underwent a battery of assessments that included the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV and a Psychiatric Social History Schedule. If patients were found to meet the aforementioned criteria for study participation, their current medication was changed to haloperidol administered at a dose equivalent to that of their current neuroleptic. During the 2 weeks just before randomization, patients received 8 mg of haloperidol daily. At this dose, patients underwent their baseline assessments, which included scales that measured clinical psychopathology, side effects, social adjustment, and subjective response. We selected 8 mg for the stabilization period for two reasons. First, it was a dose that most patients would tolerate. Second, most patients would experience a decrease in side effects at the time of randomization, since their drug dose would be decreased or they would be changed to a different agent.

Drug Treatment Conditions

At the time of randomization, patients discontinued their open-label haloperidol and began double-blind treatment with risperidone or haloperidol. The initial dose of drug was 2 mg t.i.d. for the first week and then 6 mg h.s. of haloperidol or risperidone. Subjects were seen at least weekly by a study psychiatrist during the first month of the study and monthly during the remaining months. Patients continued receiving their original fixed dose for as long as they remained stable. When patients experienced a psychotic exacerbation, the dose of study drug was increased by 2 or 4 mg up to a total daily dose of 16 mg (of haloperidol or risperidone). Psychotic exacerbation was defined as a worsening of 4 points or more on the sum of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) cluster scores for thought disturbance and hostile-suspiciousness or an increase of three or more on either one of these clusters. In addition, at least one item needed to have a score of 4 or greater. After patients recovered from exacerbations, the research psychiatrist had the option of readjusting the drug dose. If patients experienced three exacerbations or if continuing in the study was not in the patient’s best interest, they were discontinued from the drug component of the study. This occurred when it was the opinion of the patient and the clinician that the patient had previously responded better to another agent. When patients were dropped from the drug component, they were permitted to continue in their psychosocial condition (although for the data analysis of this report, they were considered as having left the trial). Patients who experienced extrapyramidal or other side effects had their dose lowered to 4 mg and subsequently a single 2-mg pill at bedtime. Whenever possible, antiparkinsonian medications—both anticholinergic agents and propranolol—were reduced and then discontinued.

Psychosocial Treatment Conditions

The psychosocial conditions have been described in detail in another publication from this study

(7). Briefly, all subjects participated in a series of skills training modules on medication management, symptom self-management, social problem solving, and successful living during the first 15 months following randomization

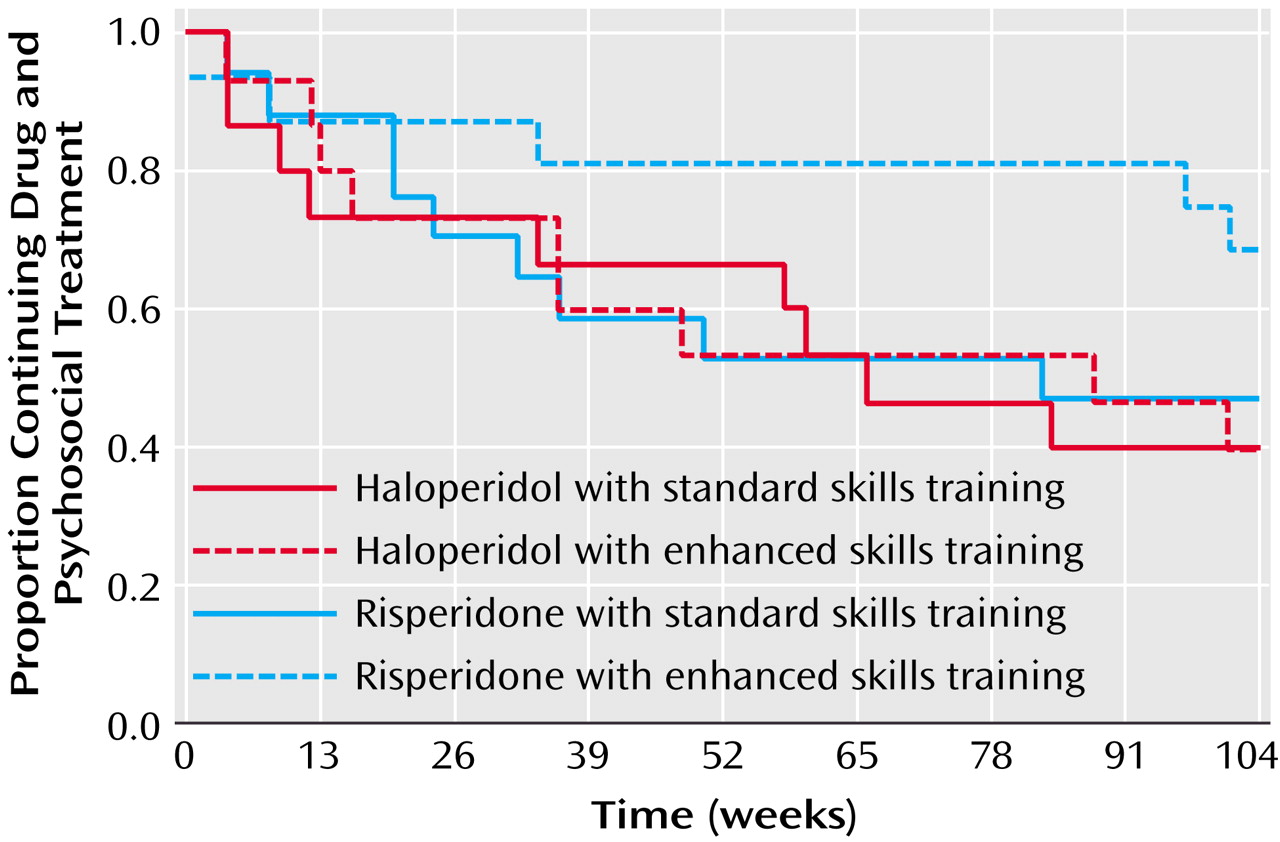

(9). One-half of the study subjects were randomly assigned to additional In Vivo Amplified Skills Training, a behaviorally oriented, manualized intervention that supported the clinic-based skills training by providing opportunities and encouragement for utilizing skills in the community. Examples of In Vivo Amplified Skills Training activities included visiting a pharmacy to find remedies for dry skin or dry mouth, learning to use public transportation to make medical appointments, or getting a library card and learning to use the library.

Assessment of Clinical Outcomes

Clinical psychopathology was rated with the BPRS

(10) and the Schedule for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)

(11). Subjective response was rated with the SCL-90-R

(12). Side effects were rated with the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale

(13), the Barnes Akathisia Scale

(14), and the Modified Simpson-Angus Rating Scale

(15). The primary measures of social functioning were the Social Adjustment Scale II

(16) and the Quality of Life Scale

(17). All assessments were conducted at pretreatment, 9 months, 15 months, and 24 months.

Participant Flow

The 63 patients who were randomly assigned to a treatment condition were derived from a group of 110 patients who were considered eligible for participation. Of the 47 who were not randomly assigned, 10 could not be adequately stabilized, eight were unable to tolerate haloperidol during the stabilization phase, five left the medical center against medical advice, seven withdrew consent, seven did not return for appointments and could not be located, three were noncompliant with study procedures, three left the Los Angeles/Long Beach area, two refused group treatments, and two abused street drugs during the stabilization period. Of the 63 patients randomly assigned to a treatment condition, 29 completed the 2 years of the trial. We compared patients who eventually completed and those who eventually left the study. We found no differences in demographic characteristics (age, education level, duration of illness, ethnicity) or clinical dimensions (BPRS scores). We also used proportional hazards regression with time-dependent covariates to see if the risk of dropout was related to psychopathology; separate models were used to evaluate baseline, last available measurement, and drug as predictors of dropout. Again, we found no effects.

Data Analysis

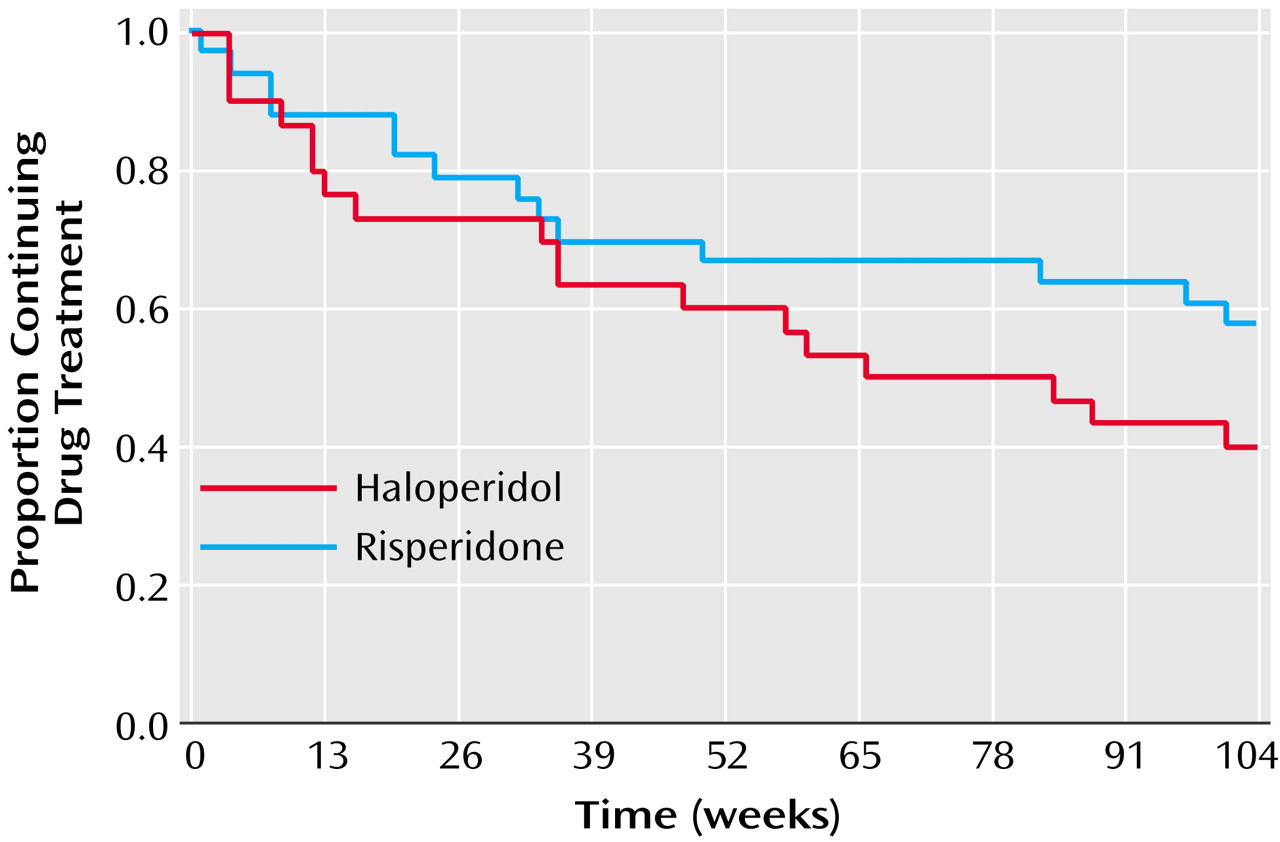

The analysis of continuous variables was done by using general linear mixed model analyses of covariance with repeated measures at measurement points up to 2 years. Design effects were medication group and time (and their interaction), with baseline score used as a covariate and change from baseline as the dependent variable. Use of the change score produces the same statistical results in the covariance model as would be obtained with use of posttreatment scores but permits testing of within-group changes in the same analysis as testing of between-group differences. In the absence of medication group-by-time interactions, main effects of medication treatments are presented. Survival analysis of time to dropout, exacerbation, and composite criteria was done by using the Kaplan-Meier method. Significance was set at the p=0.05 level. The mixed model analysis of variance method used here is a univariate design that does not offer multivariate significance tests (experimentwise adjustment) across several dependent measures. The results reported below are presented without adjustment of p values for multiple comparisons.

Discussion

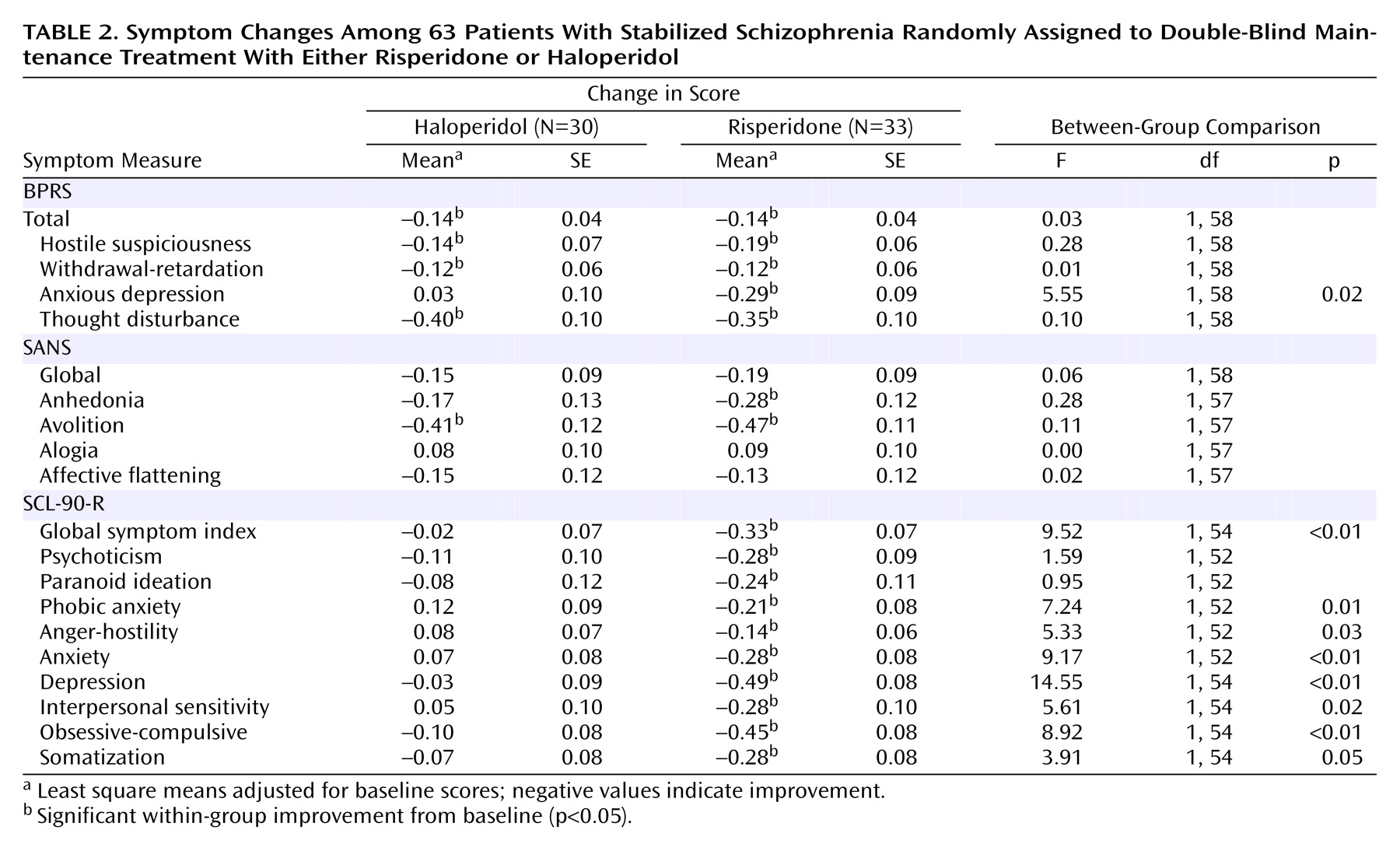

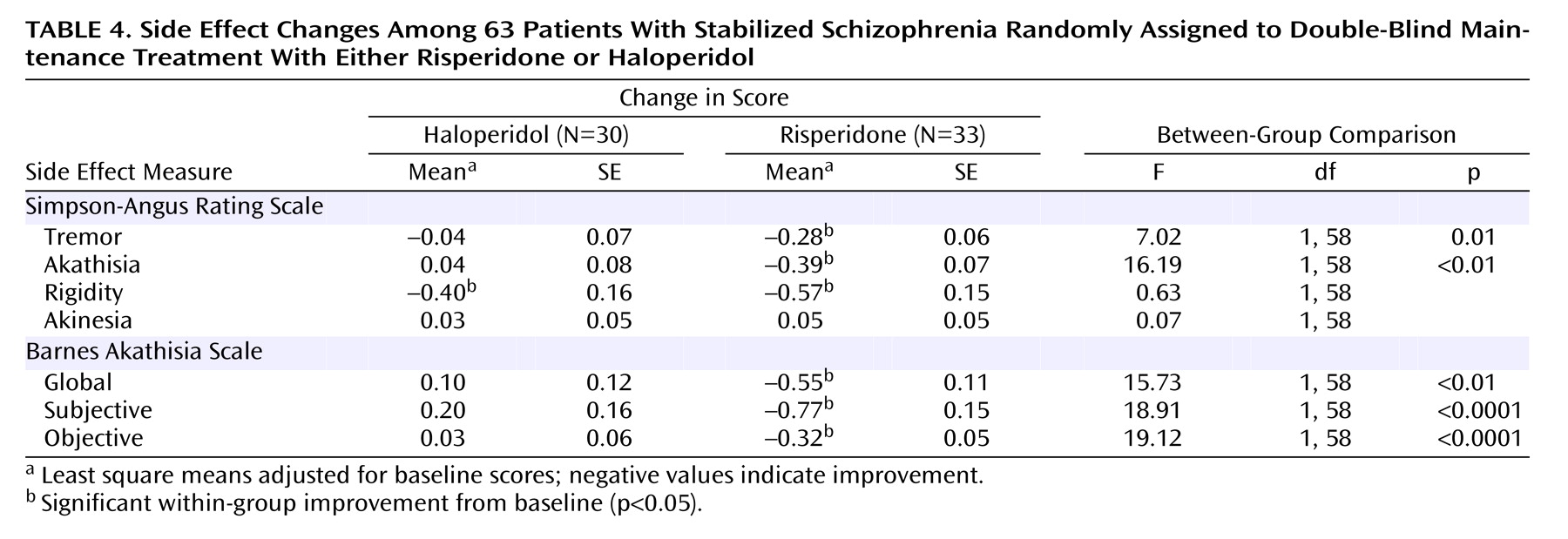

This study is among the first to compare a second-generation antipsychotic with a low dose of a conventional agent during maintenance therapy for schizophrenia. The findings indicate that both agents were effective in preventing relapse and minimizing positive and negative symptoms. The important differences between the agents were in items that measured mood and anxiety such as the anxious-depression cluster of the BPRS and multiple subscales on the SCL-90-R. These items favored risperidone. In addition, risperidone was associated with less tremor and akathisia.

The finding that risperidone was associated with less depression and anxiety is consistent with results from other reports that compared newer and older antipsychotics. An 8-week study that compared multiple fixed doses of risperidone and haloperidol

(19) found that the largest differences between older and new agents were in items that measured mood and anxiety. A 29-week study that compared clozapine and haloperidol also found that the largest difference between the two drugs was in the same BPRS cluster measuring anxious depression

(20). A prior study from our group

(21) found that higher doses of fluphenazine decanoate were associated with similar increases on items from the SCL-90-R and in akathisia. We interpreted those findings as indicating that higher doses were associated with more extrapyramidal side effects which, in turn, led to an antipsychotic-induced dysphoria that was manifest in anxiety and depression. Given the high scores in rating scales measuring tremor and akathisia in patients receiving haloperidol, the findings from this study are consistent with the interpretation that the advantage of risperidone in mood and anxiety is associated with its advantage in extrapyramidal side effects.

Other studies have suggested that second-generation antipsychotics have intrinsic mood elevating or antidepressant activities. For example, short-term studies with clozapine

(22), risperidone

(23), and olanzapine

(24) have found that the second-generation agent was associated with less depression than a conventional agent. Although data analytical methods have suggested that the advantages of the newer agent in mood are not related to extrapyramidal side effects

(19,

25), these post hoc methods have limitations in that the subjective discomforts that may occur with very mild extrapyramidal side effects are difficult to measure. In our view, the difference in extrapyramidal side effects liability between the two agents remains a reasonable explanation of the findings in our study.

We did not find advantages in negative symptoms as measured by the SANS in patients receiving risperidone. This is inconsistent with short-term studies that have found significant advantages in negative symptoms for risperidone over haloperidol

(23,

26). However, a meta-analysis of short-term studies that compared selected second-generation antipsychotics and haloperidol

(27) found that the effect sizes were very small for the advantages of risperidone and olanzapine when compared with haloperidol. It is conceivable that the effect sizes were too small to be detected in this study. Another possibility is that the advantages in negative symptoms seen in short-term studies are actually advantages in secondary negative symptoms rather than core negative symptoms. That is, patients who receive older antipsychotics are more likely to have forms of akinesia that may be manifest in decreased spontaneous movements and diminished speech. This difference would be recorded as higher scores on the SANS. This difference would be less likely to occur in long-term studies when doses of the older antipsychotic were lower. This interpretation is supported by studies that focused on clozapine. A short-term study that compared clozapine to chlorpromazine

(22) found an advantage for clozapine in BPRS items that appeared to monitor negative symptoms. However, studies that compared clozapine and haloperidol over 6 months

(20) and 1 year

(3) did not find significant differences in negative symptoms. A report by Kopelowicz and co-workers

(28) suggests that olanzapine has advantages for secondary negative symptoms but not primary negative symptoms. On the other hand, the relapse prevention study comparing risperidone and haloperidol

(3) found a statistically significant advantage for risperidone.

The doses we administered to patients may have affected the study results. At the time this study was initiated, 6 mg of risperidone was recommended for acute and chronic treatment. Prescribing practices of clinicians suggest that 4 mg/day is probably a more appropriate dose for acute treatment as well as maintenance. On the average, patients assigned to haloperidol received less than 5 mg/day. We are unaware of other studies that have monitored relapse prevention at this dose. Patients in the study by Csernansky et al.

(3) received a mean dose of haloperidol of 11.7 mg/day, and an extension study of responders to olanzapine and haloperidol

(5) administered haloperidol at a dose of 13.5 mg/day. Our comparison of a lower dose of haloperidol and 6 mg of risperidone may have given risperidone a small advantage. However, it is notable that even when patients received a low dose of haloperidol and aggressive treatment with antiparkinsonian agents—as they did in this study—there was still an advantage for risperidone in measures of extrapyramidal side effects.

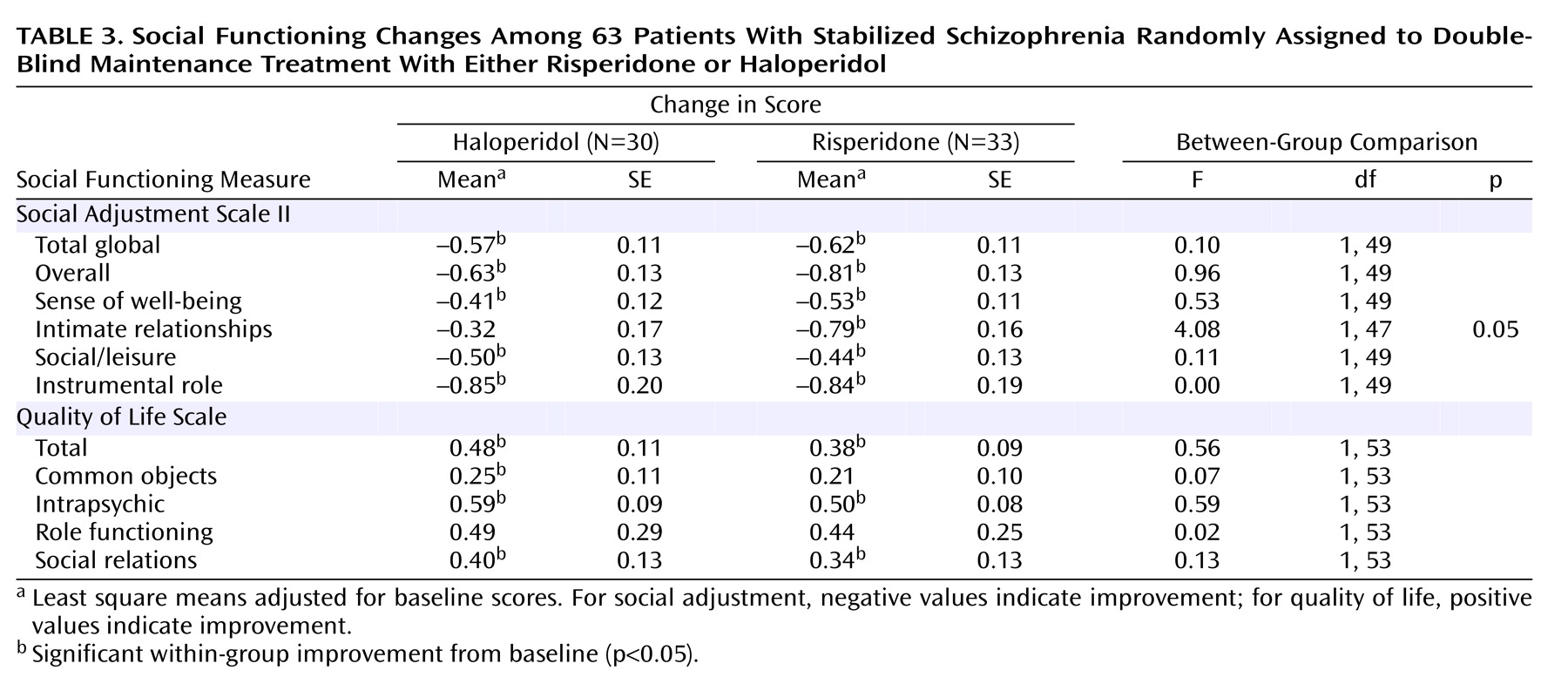

We also found that patients in both study conditions—risperidone at doses of about 6 mg/day and haloperidol at 5 mg/day—demonstrated symptom improvements along with improvements in social adjustment. The latter improvements may have resulted from the behavioral skills training that was received by all of the study patients and which was previously shown to improve social adjustment

(29). The improvement associated with haloperidol treatment may have been due to the reduction of the daily haloperidol dose from 8 mg to 5 mg. Although dosage comparisons have been carried out with long-acting antipsychotics during maintenance therapy, there is relatively little information available regarding the most effective dose of haloperidol for stabilized patients. Our results suggest that 5 mg may be somewhat more effective than higher doses.

We also found evidence suggesting an interaction between pharmacological treatment and participation in psychosocial treatment. When we evaluated dropout for any reason using survival analysis, patients who received risperidone and clinic-based skills training with In Vivo Amplified Skills Training, our experimental psychosocial condition, demonstrated the best survivals. Given the milder side effect profile of risperidone and our finding of less anxiety and depression with this second-generation antipsychotic, it is possible that this subjective advantage led patients to derive greater benefit from In Vivo Amplified Skills Training. Other possible effects would be advantages in primary or secondary negative symptoms or neurocognition with risperidone. These results resemble findings from a study by Rosenheck et al.

(30) in which patients who received clozapine were more likely to participate in psychosocial treatments.

It is important to note that the possible advantages of combining risperidone with In Vivo Amplified Skills Training were related to remaining in the study. We did not find a significant advantage in social outcomes associated with the combination. However, as noted in a prior publication from this study

(7), patients who received In Vivo Amplified Skills Training demonstrated greater improvements in social adjustment than patients who received standard skills training only.

There were a number of limitations to this study. The study group size limited our power to test a number of important questions in maintenance treatment. For example, a larger study group size may have revealed significant differences in the risk of relapse or the patients remaining in their drug condition. In addition, the study had a substantial dropout rate, which further limited the patients we could evaluate at the end of 2 years. However, our dropout rate was similar to that of other long-term trials in schizophrenia

(3). In addition, the study did not evaluate the overall side effect burden associated with the study conditions. For example, we did not systematically monitor important side effects such as weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and the risk of diabetes.

In summary, our results indicated that risperidone, a second-generation antipsychotic, and haloperidol, a conventional antipsychotic, led to similar improvements in positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia as well as low rates of relapse. However, patients who received risperidone experienced greater improvements in anxiety and depression as measured by clinician and self-ratings. These advantages of risperidone are likely to be important if they facilitate participation in psychosocial treatment, as they appeared to in this study.