Data Set

Among several thousand citations, we located 551 candidate articles, which provided 111 class A trials (81 monotherapy trials, 30 combination therapy trials; the findings from the combination trials are not presented because of space limitations, but the results are available from the first author on request). Monotherapy trials provided 95 independent analyses, including 48 for treatment of acute mania, 16 for acute depression, and 31 for prophylaxis.

Several classic trials were excluded because of a lack of study group statistics (e.g., references

25 and

26) or a lack of separation of bipolar disorder subjects from subjects with other disorders (e.g., reference

27). Several earlier reports were superseded by later extensions of the same dataset (e.g., references

28 and

29). Two prophylaxis trials were included, although they focused on subsets of bipolar disorder patients, such as those with rapid cycling

(30) or with comorbid borderline personality disorder

(31). One trial of treatment for acute mania was excluded because it lasted for only one day

(32).

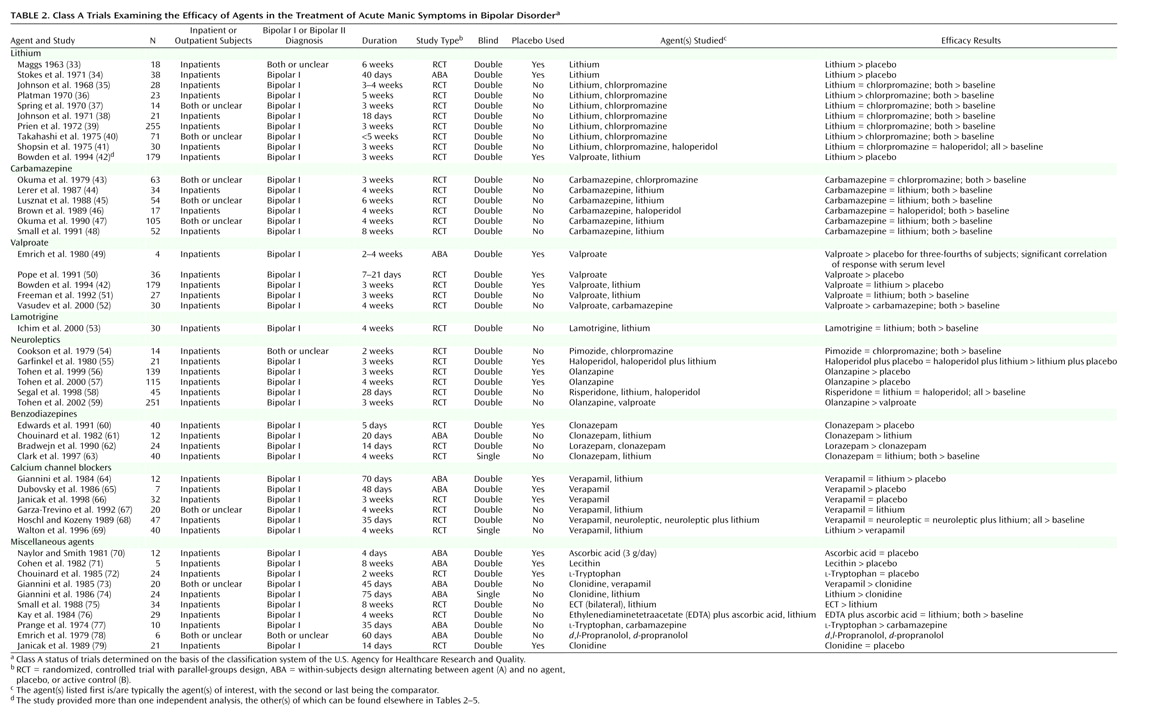

The trial characteristics and results are summarized in

Table 2,

Table 3, and

Table 4. For treatment of acute mania, at least one positive placebo-controlled trial supported the efficacy of lithium, valproate, haloperidol, olanzapine, clonazepam, verapamil, or lecithin. In addition, evidence from at least one active control trial supported the efficacy of carbamazepine, lamotrigine, pimozide, risperidone, lorazepam, ECT, ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA) plus ascorbic acid,

l-tryptophan, and

d,

l-propranolol.

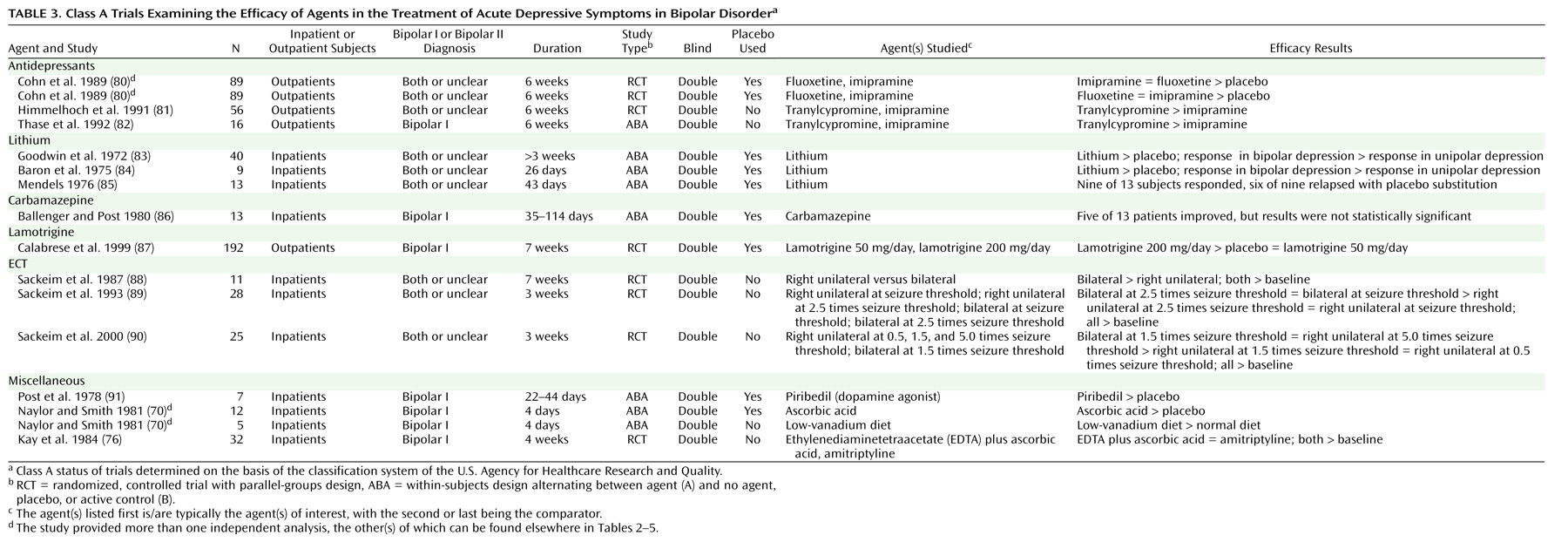

In acute depression, at least one positive placebo-controlled trial supported the efficacy of fluoxetine, imipramine, lithium, lamotrigine, piribedil, and ascorbic acid. Evidence from at least one active control trial supported the efficacy additionally of tranylcypromine, ECT, a low-vanadium diet, and EDTA plus ascorbic acid.

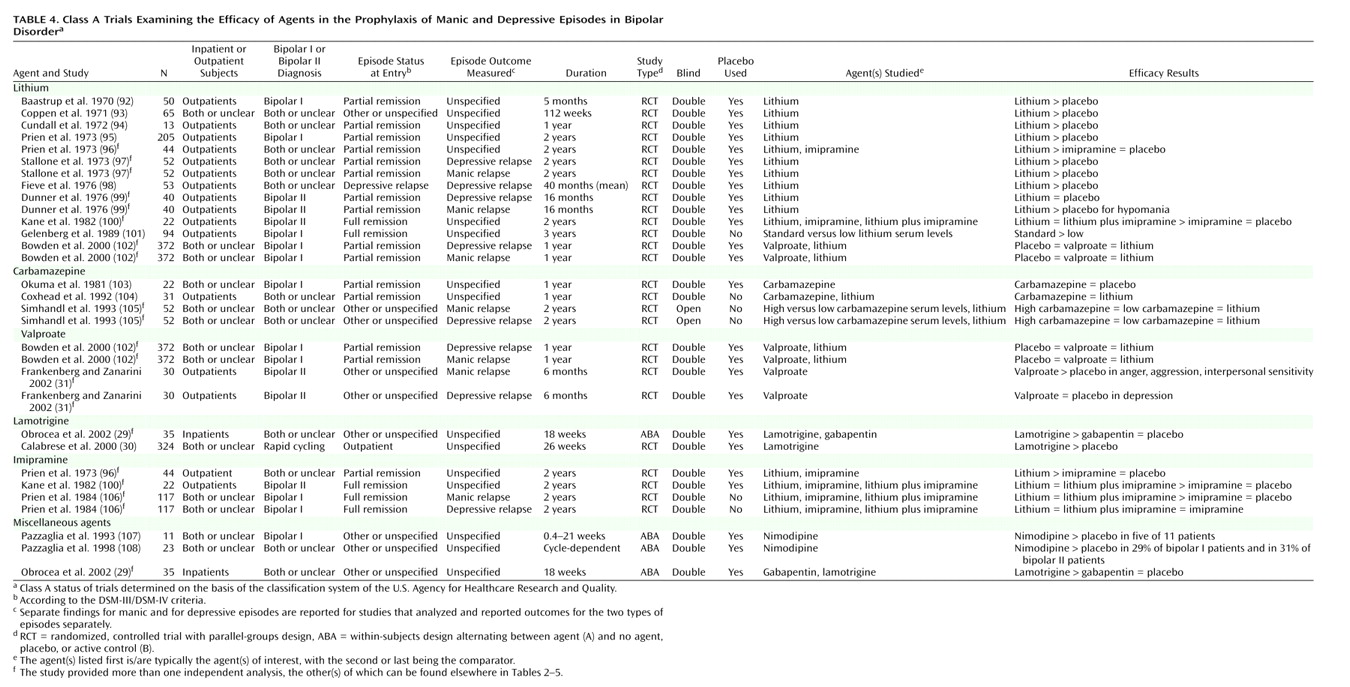

At least one positive placebo-controlled trial supported the prophylactic efficacy of lithium, valproate, and lamotrigine, with one trial indicating a trend toward significant effects of carbamazepine versus placebo

(103). No additional agents were supported by evidence from active control trials. However, one trial showed equivalence among low- and high-dose carbamazepine and lithium for prophylaxis of both mania and depression

(105), and one trial showed equivalence between carbamazepine and lithium

(104). These are not ranked as positive trials because they did not meet the a priori criteria of both including data indicating improvement over baseline and exceeding effects of comparator(s).

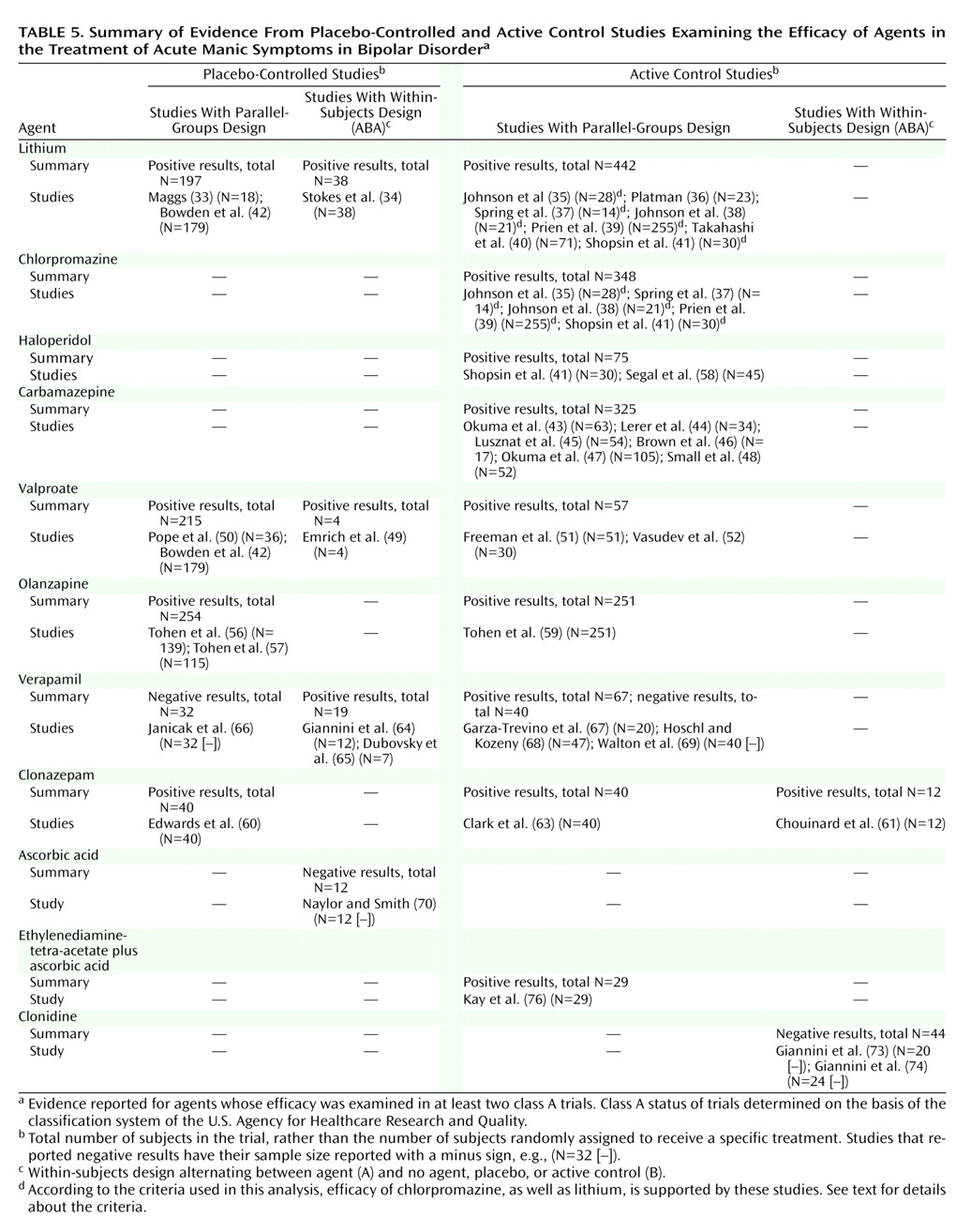

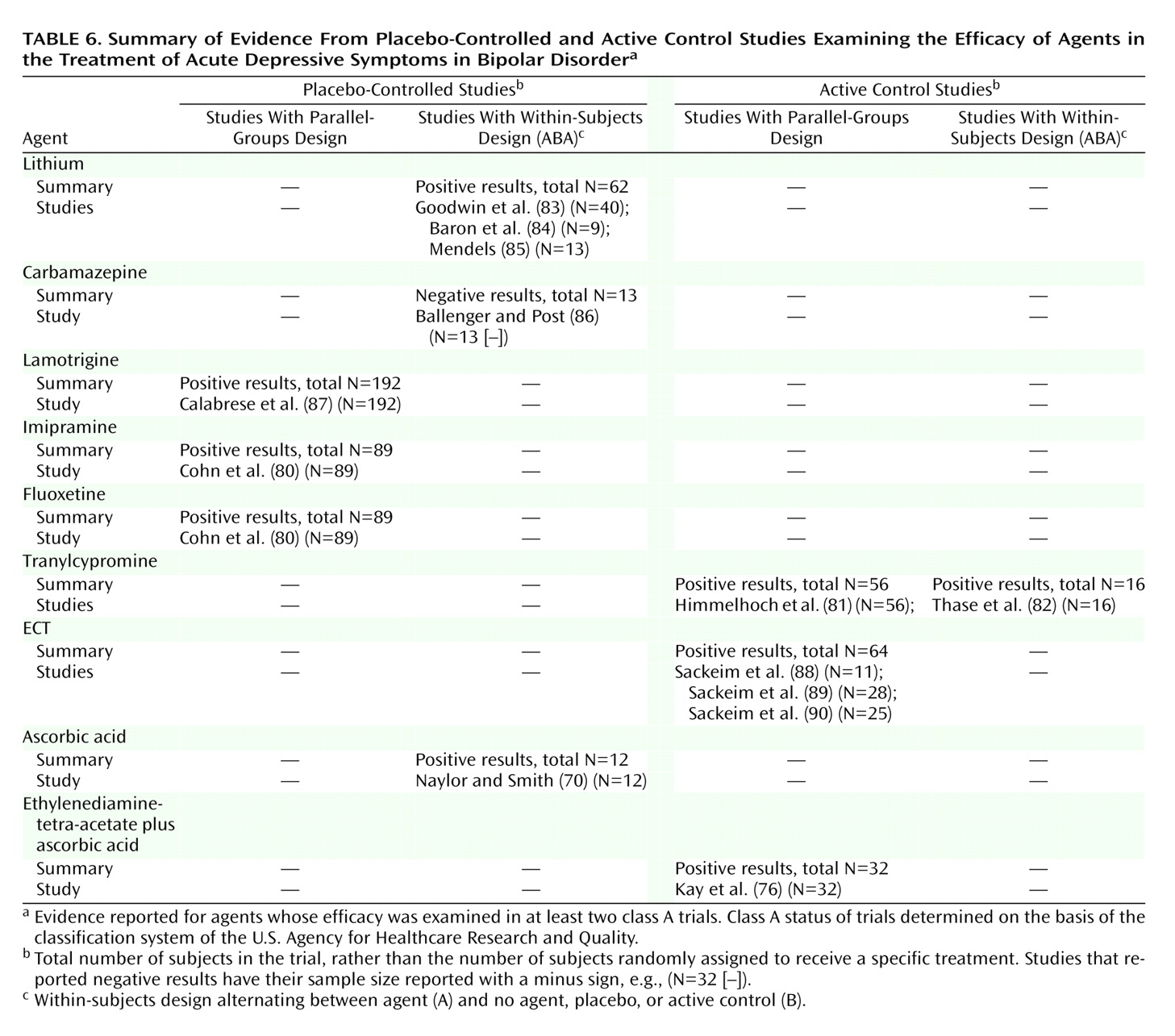

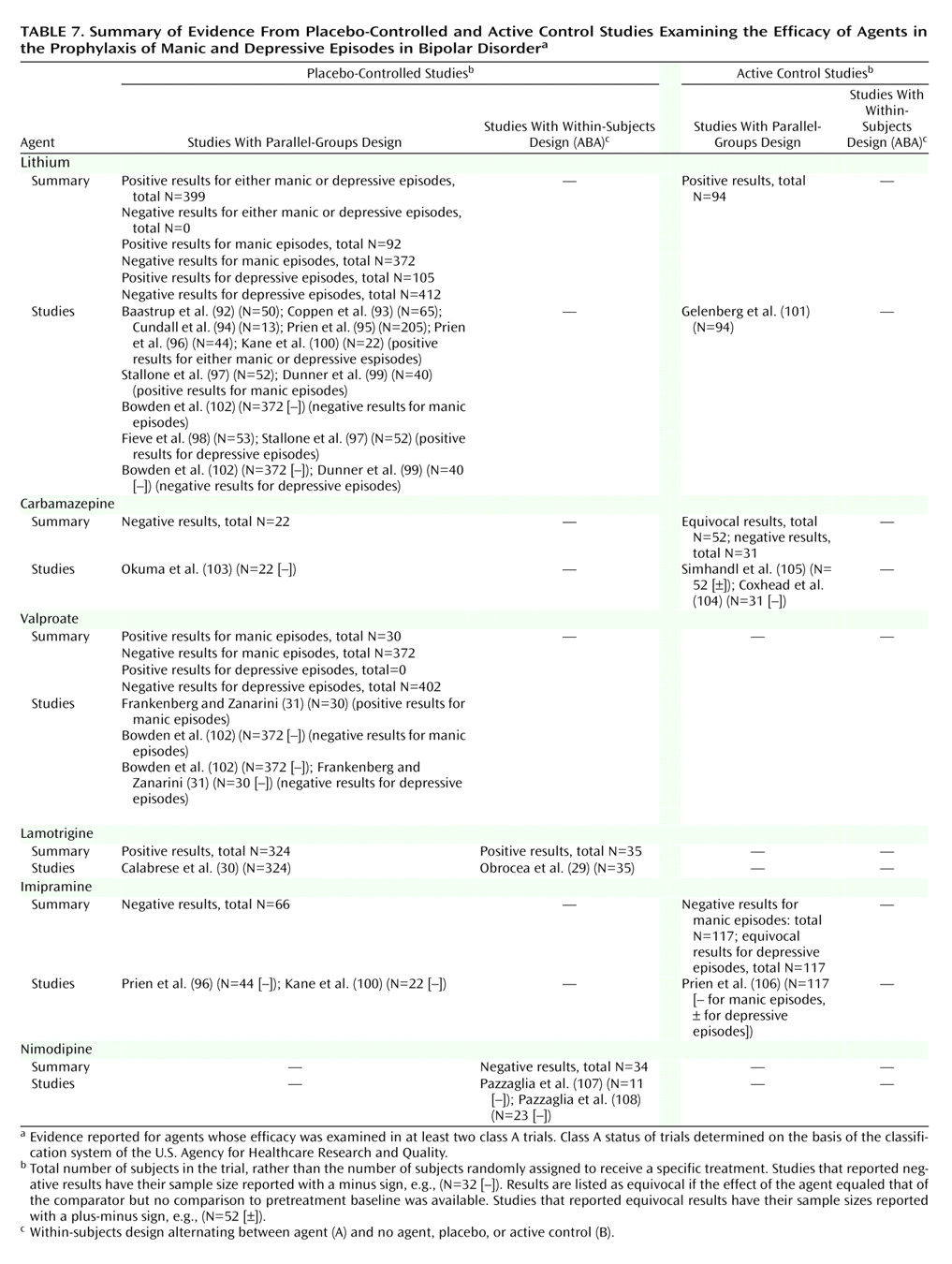

Candidate Mood Stabilizers According to the “Two-by-Two” Definition

Data for agents that had at least two class A trials (positive or negative), as shown in

Table 2,

Table 3, and

Table 4, and that were therefore candidates for mood stabilizer status, are summarized in

Table 5,

Table 6, and

Table 7. These tables are organized with the highest quality trials (placebo-controlled, parallel-groups trials) listed in the leftmost column, other placebo-controlled (ABA) trials in the next column to the right, and active control trials following rightward.

The trial quality threshold can be conceptually “moved” to the left to raise the evidence threshold or to the right to relax the requirement in a post hoc categorical sensitivity analysis. Although this categorical analysis does not formally distinguish the weight of evidence on the basis of sample size (as a meta-analysis would indirectly do), interpretation of the findings can be tempered by inspection of such considerations, as noted below. Further, no notation is made as to whether a trial was adequately powered for specific comparisons. In most trials the authors did not comment on power, although the authors who did comment sometimes noted insufficient power (e.g., in a study of lithium versus placebo for prophylaxis

[100]); nevertheless, by convention such trials are listed, as are those for which no comment on power is available.

For acute mania, lithium, valproate, and olanzapine unequivocally meet the definition criteria. They continue to meet the criteria if the threshold is raised to include only parallel-groups, placebo-controlled trials. Verapamil presents an equivocal case, which can easily be detected with this data array method. Its antimanic efficacy is supported by two positive placebo-controlled trials; however, the total number of subjects in these two trials, 19, is less than the 32 treated in a higher-quality negative trial. If the criterion is relaxed to include also active control trials, carbamazepine and clonazepam are included, and the evidence for verapamil is strengthened somewhat. Note also that chlorpromazine, the comparator for lithium in early trials, is also included by virtue of its being equal to lithium and better than baseline in five trials summarized in

Table 2 (35,

37–

39,

41), although it is inferior to lithium but still better than baseline in two trials

(36,

40). Haloperidol is also included by virtue of one placebo-controlled trial

(55) and one active control trial

(41).

For acute depression, only lithium is supported by placebo-controlled trials; however, none of these trials had a parallel-groups design. Relaxing the criterion to allow active control trials allows tranylcypromine and ECT to be included.

For prophylaxis, lithium and lamotrigine are each supported by at least two placebo-controlled trials, with the two lamotrigine trials providing analyses without regard to relapse polarity. Lithium is supported by five trials analyzing relapse to either episode, plus two trials reporting relapse specifically to mania and two reporting relapse specifically to depression; one trial, although underpowered for lithium

(100), provided negative data for each polarity, and one trial

(97) also provided negative data for depression prophylaxis. Evidence for a prophylactic role for valproate is equivocal, with primary analyses negative for mania and depression in the large trial of Bowden and co-workers

(102), plus another trial that included subjects with comorbid personality disorder and that reported positive results for manic-like symptoms and negative results for depressive symptoms using measures relevant to, but not specific for, manic and depressive episodes

(31).

Lithium also meets the higher threshold requiring parallel-groups, placebo-controlled evidence for manic

(97,

99) and depressive

(97,

98) episode prophylaxis, while lamotrigine does not

(29). Relaxing the criterion to admit active control trials allows inclusion of three equivocal trials for carbamazepine that showed equivalence to lithium but no evidence for improvement over baseline.

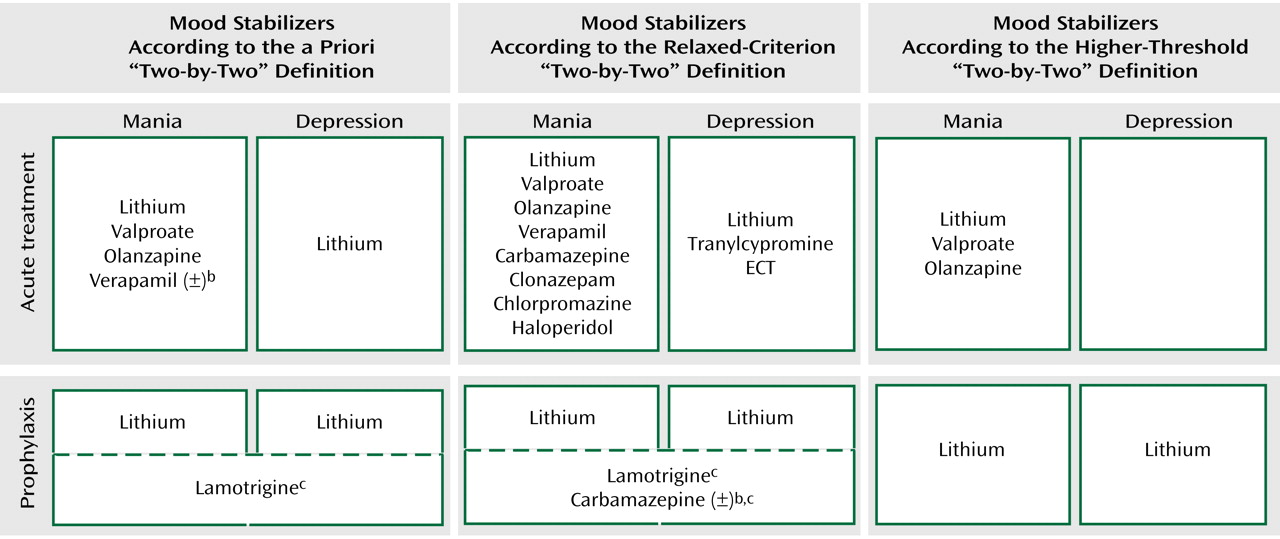

Figure 1 combines data from the foregoing tables for each of the four mood stabilizer uses according to the a priori definition and the sensitivity analyses. Only lithium fulfills the a priori definition. Relaxing the criterion to allow active control trials as evidence does not change this result. Raising the threshold to require at least two

parallel-groups, placebo-controlled trials results in no single agent fulfilling the definition.

Looser Definition of Mood Stabilizer

The looser definition of mood stabilizer noted in the introduction—an agent with efficacy in decreasing the frequency or severity of any type of episode in bipolar disorder while not worsening the frequency or severity of other types of episodes—is actually difficult to evaluate in the clinical trials literature. While many agents have efficacy in at least one use (

Figure 1), few trials measured the outcomes of both manic and depressive symptoms concurrently, and lack of evidence of a negative effect does not mean no negative effect.

Two acute mania trials showed improvement in both manic and depressive symptoms, as noted earlier

(48,

59), so it is unlikely that these agents worsen either type of episode, at least in the short term. Comparing data across controlled trials, no trials reported that the agent of interest had worse performance than placebo or that the outcome of treatment was worse than baseline. One therefore must rely on noncontrolled trial data to draw conclusions about an agent’s negative effects on course. This approach is clearly needed in the case of antidepressants

(109), although the degree of risk from these agents versus other factors

(110) and the specific agents of risk remain controversial

(111). Thus, the looser definition of mood stabilizer is surprisingly difficult to address with class A data.