Measures

During each interview wave, we assessed the occurrence over the last year of 14 individual symptoms that represented the disaggregated nine A criteria for major depression in DSM-III-R (e.g., two items for criterion A4 to assess separately insomnia and hypersomnia). For each reported symptom, interviewers probed to ensure that it was due neither to physical illness nor to medication. The respondents and interviewers then aggregated symptoms reported for the last year into co-occurring syndromes. If depressive syndromes occurred, the respondents were asked when each one occurred and the months of its onset and offset. To be eligible for the occurrence of a new depressive episode, the respondent had to report being basically symptom free and “back to his/her normal self” for at least 2 weeks. The diagnosis of major depression was made by a computer algorithm incorporating the DSM-III-R criteria, except criterion B2 (which excludes “uncomplicated bereavement”). In 375 twins interviewed twice by different interviewers with a mean interinterview interval of 30 days (SD=9), the interinterview reliability of the diagnosis of major depression in the last year was good: the kappa

(20) value was 0.68, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.57–0.80, and the tetrachoric correlation coefficient was 0.92, with a 95% CI of 0.86–0.98.

Neuroticism was measured by using the 12-item scale from the shortened Eysenck Personality Questionnaire

(21). Three representative items for this scale were 1) “Are you the type of person whose feelings are easily hurt?”; 2) “Are you the type of person who is rather nervous?”; and 3) “Are you the type of person who is a worrier?” In this study, we took the levels of neuroticism reported from wave 1 of both the female-female and the male-male and male-female samples. Our interviews assessed the occurrence, to the nearest month, of 11 “personal” stressful life events (events occurring primarily to the informant): “assault” (assault, rape, or mugging), “divorce/separation” (divorce, marital separation, broken engagement, or breakup of other romantic relationship), “major financial problem,” “serious housing problems,” “serious illness or injury,” “job loss” (laid off from a job or fired), “legal problems” (trouble with police or other legal trouble), “loss of confidant” (separation from other loved one or close friend other than a spouse or partner), “serious marital problems,” (involving a marital or marriage-like intimate, cohabiting relationship), “robbed,” and “serious difficulties at work.” We also assessed four classes of network events, meaning events that occurred primarily to, or in interaction with, an individual in the respondent’s social network. Network was here defined as spouse, child, parent, sibling, other close relative, or “someone else close to you.” These event classes consisted of 1) “getting along with”—serious trouble getting along with an individual in the network, 2) “crisis”—a serious personal crisis of someone in the network, 3) “death”—death of an individual in the network, and 4) “illness”—serious illness of someone in the network.

Each reported stressful life event in waves 3 and 4 of the female-female sample and wave 2 of the male-male and male-female sample was rated by the interviewer on the level of long-term contextual threat. “Long-term” was defined as persisting at least 10–14 days after the event. Following the practice of Brown, we instructed our interviewers to rate “what most people would be expected to feel about an event in a particular set of circumstances and biography, taking no account either of what the respondent says about his or her reaction or about any psychiatric or physical symptoms that followed it”

(22, p. 24).

Long-term contextual threat was rated on a 4-point scale: minor, low moderate, high moderate, and severe

(22). The reliability of our ratings was determined by interrater and test-retest designs. Interrater reliability was assessed by having experienced interviewers review tape recordings of the interview sections in which 92 randomly selected individual stressful life events were evaluated. Test-retest reliability was obtained by repeating the interview with 191 respondents at a mean interval of 4 weeks. We obtained 173 scored life events that appeared to be consistent in the two interviews; the subject described the event similarly in both interviews and placed it in the same 1-month period. We assessed reliability by Spearman correlation (r

s) and weighted kappa

(23). The test-retest reliability for long-term contextual threat was r

s=0.60 and kappa=0.41, while the interrater reliability was r

s=0.69 and kappa=0.67.

Statistical Methods

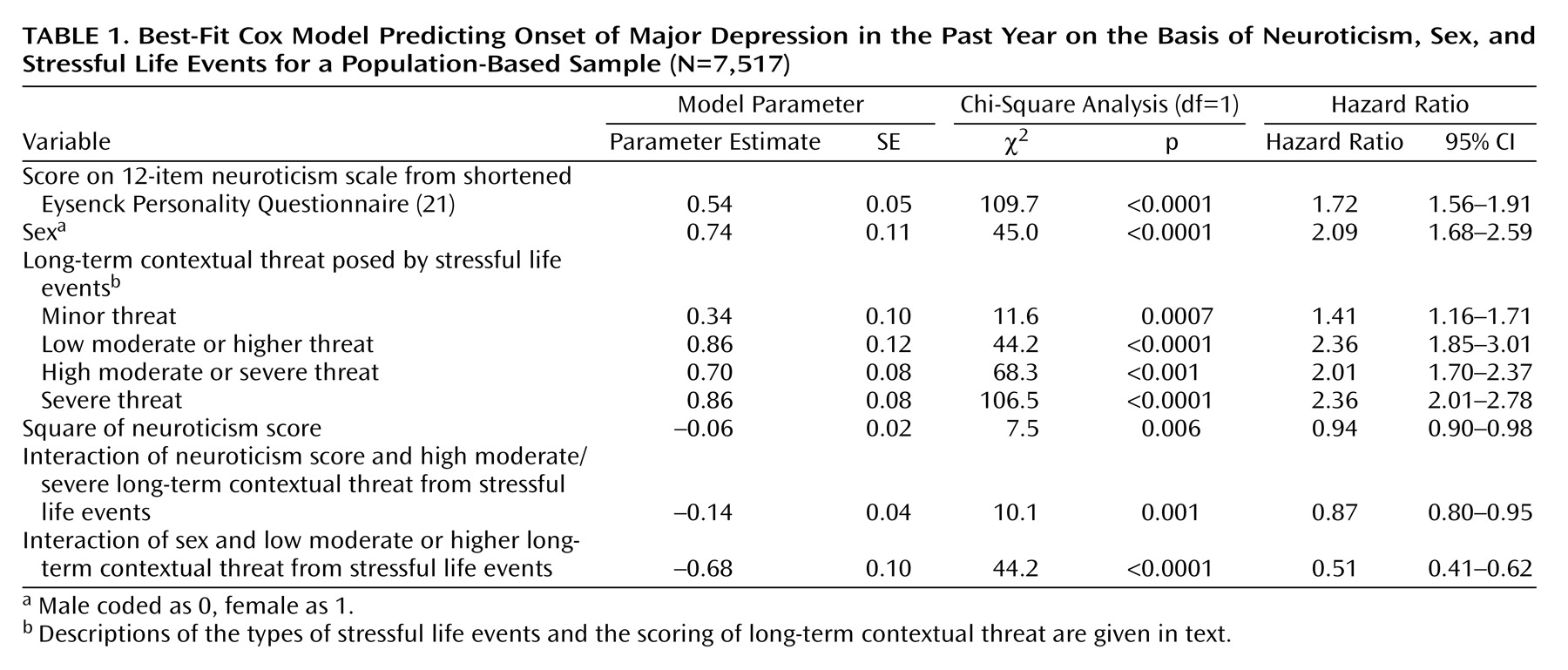

Person-months were used as the unit of analysis, and the analyses were conducted with a Cox proportional hazards model operationalized in the SAS procedure PHREG

(24,

25). Three predictor variables were used: neuroticism, sex, and long-term contextual threat. When multiple events occurred in the same month, long-term contextual threat was coded as the highest threat level of any recorded event. The dependent variable was the onset of a depressive episode.

The final model was developed on the basis of nine strata. Each stratum consisted of data for subjects who had a specific number of prior onsets and participated in one interview wave—specifically zero, one, or two prior onsets in the past 13 months for subjects from the three included waves. There were too few subjects with three or more onsets to include such data. This stratification is a conservative way to deal with within-subject correlation. An 18-strata model was also developed in which twins were randomly assigned to two separate groups to conservatively evaluate the impact of familial correlations. Coding was done on the basis of the “conditional A” model proposed by Hosmer and Lemeshow

(26).

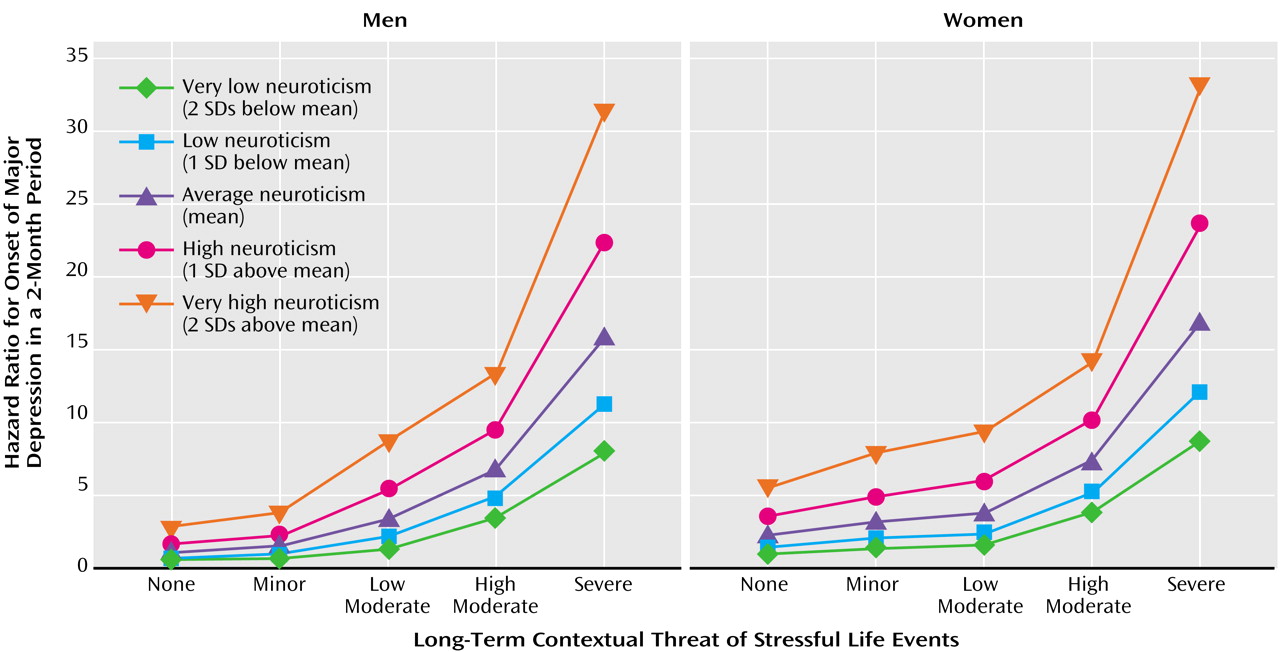

Neuroticism was standardized to have a mean score of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, allowing easy interpretation and a meaningful quadratic term. Long-term contextual threat was coded so that 0 meant no stressful life event during the month and 1 through 4 meant the occurrence of a stressful life event with minor, low moderate, high moderate, or severe long-term contextual threat. To incorporate the ordinal structure and simplify interpretation of the interaction, long-term contextual threat was coded as follows: four dummy variables X1, X2, X3, and X4 were used. If there was no stressful life event, all four were coded as 0. If there was a significant life event with a threat scored as at least 1, X1 was coded as 1. If the threat was scored as at least 2, X2 was also coded as 1. If the threat was scored as at least 3, then X3 was coded as 1. For an event with a threat level scored as 4, all four dummy variables were coded as 1. Thus, the coding for a month with an event with a long-term contextual threat scored as 2 was as follows: X1=1, X2=1, X3=0, X4=0. This method of dummy variable coding is often referred to as “thermometer coding”

(27). Finally, the dummy variables were incorporated as a time-dependent covariate with a linear decay that abated after 3 months. The final model was found by starting with all three-way interactions and eliminating nonsignificant terms.

In these analyses, the dependent variable—a depressive episode—was dichotomous, and this fact introduced unavoidable complexity into our analyses. We were interested in clarifying the nature of the interaction between personality and adversity, and from a statistical perspective, any interaction is scale dependent. A Cox regression model has advantages in these analyses. However, instead of predicting the probability of outcome p, the model predicts a logarithmic transformation of p. Because the dependent variable is a logarithmic function, the nature of what an interaction means changes. What is a multiplicative interaction in the raw probability model becomes additive in the Cox model, while what is additive in the raw probability model becomes a negative interaction in the Cox model. Because a Cox model formally tests deviations from a multiplicative relationship between neuroticism and adversity in the prediction of depressive onsets, we also developed and applied a model that formally tests deviations from an additive relationship.

Information for these analyses came from a total of 7,517 individuals who participated in waves 3 and 4 of the female-female sample and wave 2 of the male-male and male-female sample. These individuals reported a total of 1,194 onsets of major depression and 10,381 periods of observation; each period of observation began either at the start of a 1-year prevalence window or at the time of recovery from an episode and ended either at the conclusion of that 1-year window or at the time of an onset of a depressive episode. The number of these onsets that occurred with zero, one, and two prior episodes in the 13-month time period were, respectively, 771 (64.6%), 276 (23.1%), and 147 (12.3%).

The final Cox model was achieved in the following way. We started with a model consisting of 29 terms: the four long-term contextual threat indicator variables, sex, the neuroticism score, the square of the neuroticism score, and all two- and three-way interactions between them. Nonsignificant terms (i.e., p>0.05) were removed one at a time, and then the model was rerun. After 20 eliminations, the final model, which has nine terms, was reached. We repeated the elimination process, beginning with several other arbitrarily chosen terms to verify that the resulting nine-term model was the only all-significant term subset of the full 29-term model.

For our additive relative hazard model, we used the computer program R

(28) with a modified version of Fekjaer and Aalen’s implementation (http://www.med.uio.no/imb/stat/addreg/) of Aalen’s model

(29).