The relationship of sleep disturbance and alcohol use is complex. Certainly, there is evidence that alcohol use affects sleep among healthy individuals who do not have alcohol problems. As Roehrs and Roth

(1) point out in their review, alcohol can initially be associated with improved sleep onset among nonalcoholic drinkers, but tolerance to these sedative effects often develops. Individuals with alcohol dependence frequently report poor quality of sleep

(2,

3) and frequent sleep problems

(4). Even after years of abstinence, alcoholics often report persistent problems with sleep

(5), and sleep disorders may predispose alcoholics to drinking relapse

(3,

6).

The prevalence of sleep disturbance in the general adult population is high. Breslau and colleagues

(7) reported that 24.6% of a sample surveyed in Detroit reported having had insomnia at some point in their lifetime. Furthermore, prior studies have shown that use of alcohol as a sleep aid is not an uncommon practice, whereas relatively few persons with insomnia seek professional treatment

(8). For example, Johnson et al.

(9) found that 13% of adults surveyed by telephone used alcohol to aid with sleep problems. Yet, few data are available on the role of sleep disturbances as a potential risk factor for the development of problem drinking. Two analyses of the Epidemiologic Area Catchment (ECA) surveys have found that insomnia increases risk for alcohol abuse in individuals with or without baseline psychiatric disorders

(10,

11). However, both of these analyses were limited to 1 year of follow-up. With a short period of follow-up, the temporal relationship of these often chronic symptoms is difficult to assess. Breslau and colleagues

(7) assessed the incidence of psychiatric disorders among survey respondents with baseline insomnia across a 3.5-year follow-up interval and found an odds ratio of 1.7 for the development of alcohol abuse and/or dependence, which did not meet the criteria for statistical significance.

In this study, we wanted to extend prior analyses and to use prospectively gathered data from a community-based sample to assess the relationship of sleep disturbance and risk for alcohol-related problems. This analysis is based on a much longer follow-up period, compared with previous studies. We hypothesized that individuals with sleep disturbances because of worry would be more likely to develop alcohol-related problems than those without these sleep disturbances. Our rationale was that those with sleep disturbances would be more likely to drink alcohol as a sleep aid and, with time, would be at greater risk for the development of alcohol-related problems. Because sleep disturbances may be intermittent and the practice of self-medication with alcohol inconsistent over time, detection of any development of drinking problems may require a long follow-up interval. The current study uses data from a sample of survey respondents who were reinterviewed a median of 12.6 years after a baseline interview. To assess symptoms of maladaptive drinking that might not meet the full criteria for alcohol abuse and/or dependence, we assessed the occurrence of alcohol-related problems as the outcome variable in this study. In addition, because sleep disturbance related to worrying may indicate an underlying psychopathologic condition, we specifically evaluated whether the presence of anxiety or mood symptoms moderated this relationship. In other words, as opposed to simply adjusting for the presence of psychopathology in the data analyses or removing individuals with these disorders from the sample, we used stratified analyses to examine whether the relationship of sleep disturbances with problem drinking differed depending on the presence of anxiety disorders or dysphoria. We hypothesized that if sleep problems because of worry increased the risk for alcohol problems, this association may be related to the presence of some types of psychiatric symptoms.

Method

The Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Program

From 1980 to 1984, collaborators in the ECA program recruited probability samples of adult residents, 18 years of age and older, in five metropolitan areas, including Baltimore, Maryland

(12). The baseline sample of the Baltimore site was completed in 1981. Staff administered the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS)

(13) soon after sampling and again at follow-up, roughly 1 year later. All study data on alcohol use, sleep disturbances, anxiety and affective symptoms, and other covariates were gathered with the DIS and other standardized interview methods, for which validity estimates have been published

(12–

15). The participants gave written informed consent, and the protocol was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Baltimore ECA Follow-Up

Between 1993 and 1996, the original 1981 cohort of the Baltimore ECA site (N=3,481) were traced. A total of 848 respondents (24%) were found to have died, 415 could not be located, and 298 refused to participate. Of the 2,633 survivors, 73% (N=1,920) were reinterviewed. The median length of follow-up was 12.6 years. In prior analyses, it has been shown that the respondents did not differ from the other survivors with respect to age and sex

(16). Attrition was associated with drug abuse and dependence and antisocial personality disorder but not with alcohol use disorders.

Current Study Sample

Of the 1,920 individuals who were reinterviewed for the Baltimore ECA follow-up, a total of 334 were excluded because their 1981 interviews indicated the report of at least one alcohol-related problem or indicated that they met the criteria for alcohol abuse and/or dependence. An additional 49 were excluded because of missing information for the principal variables to be assessed. Thus, a total of 1,537 household residents were at subsequent risk for the development of an alcohol-related problem between the time of the baseline and follow-up interviews. These individuals composed the sample from which the incident cases of problem drinking were identified.

Measures

Sleep disturbances were assessed in two different ways for this analysis. Previous analyses had used the sleep items from the DIS (e.g., reference

11). We were particularly interested in insomnia associated with worry or distress, so we turned to the General Health Questionnaire

(17), which had been included in the baseline interview. The General Health Questionnaire comprised 20 questions about how the participant had been “feeling over the past few weeks”

(18); one of the questions was “Have you been losing sleep because of worry?” For this study, individuals who replied positively to the “more than usual” or “much more than usual” response options were categorized as having a sleep disturbance because of worry. The reference category comprised the individuals who responded “not at all” or “no more than usual.” In supplemental analyses, we also examined the relationships of simple insomnia (identified with the DIS item, “Have you ever had a period of 2 weeks or more when you had trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or with waking up too early?”) and hypersomnia (identified with the DIS item, “Have you ever had a period of 2 weeks or longer when you were sleeping too much?”) with risk for alcohol-related problems.

Incident alcohol-related problems were identified if a study participant responded positively to one of 24 questions concerning his or her pattern of alcohol use. This method is similar to those used in other analyses of this data set (e.g., reference

19). The questions corresponded to the DSM-III-R criteria from the DIS that were used to assess alcohol abuse and/or dependence during the follow-up interview. These questions included, for example, “Have you often been under the effects of alcohol or suffering aftereffects while at work or school or taking care of children?”, “Have you ever had any health problems as a result of using alcohol—such as liver disease, stomach disease, pancreatitis, feet tingling, numbness, memory problems, an accidental overdose, persistent cough, a seizure or fit, hepatitis, or abscess?”, and “Have you ever tried to stop or cut down on alcohol but found that you could not?” As a consequence, the definition of an alcohol-related problem included a range of severity. For example, some problem drinkers may have been arrested once for drinking while intoxicated but would have had no other alcohol-related occurrences, whereas others would have chronic, persistent, and daily alcohol consumption or would be alcohol dependent.

Other Variables

Potential confounding variables that were assessed included age; sex; race; marital status; educational level (dichotomized as less than 12 years of schooling versus 12 or more years of schooling); age at first intoxication with alcohol (dichotomized as early [before age 15 years] versus late [age 15 years or older]; respondents who said they had never been intoxicated were included in the “late” category); history of current or prior psychiatric or substance use disorders, including affective disorders (DSM-III diagnoses of a manic episode, major depressive episode regardless of whether bereavement is present, and/or dysthymia), anxiety disorders (obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, and/or phobia), schizophrenic disorders (schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder), and illicit drug abuse and dependence; and self-report of parental history of heavy drinking. In addition, we assessed whether the study participants utilized any medical or mental health services in the prior 6 months. Information for the assessment of these potential confounding variables was gathered from the baseline interview, with the exception of the information about parental drinking history, which was gathered at the time of a 1-year follow-up interview.

Statistical Analyses

To test our hypotheses, we completed exploratory analyses and fit a logistic regression model with the report of problem drinking at the time of the follow-up interview (presence/absence) as the response variable and the dichotomous variable of sleep disturbance because of worry (yes/no) from the baseline interview as the explanatory covariate. The logistic regression models provided statistical control of covariates with potential confounding effects. In addition, we tested for interaction between psychological disturbances (lifetime anxiety disorders and dysphoria) and sleep disturbances. As discussed previously, we also subsequently stratified the analyses, in separate models, by the presence of lifetime anxiety disorders and the presence of lifetime dysphoria.

Results

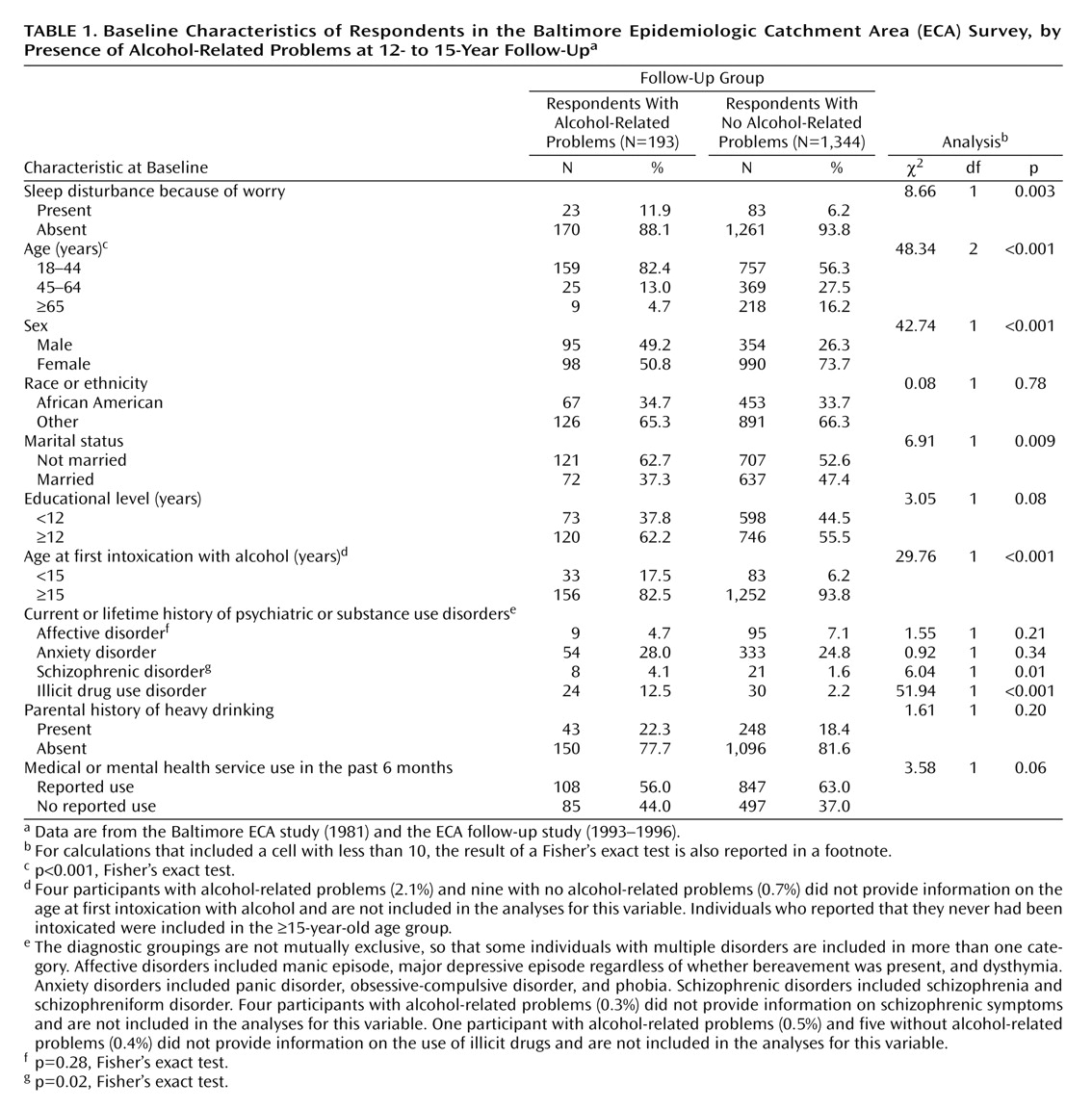

The frequency distribution of the baseline characteristics by the incident occurrence of alcohol-related problems is presented in

Table 1. The proportion of individuals with sleep disturbance because of worry was higher for problem drinkers than for those who did not develop problem drinking. Problem drinkers also were more likely to be male, to be among the youngest age group (18–44 years), and to report that the first time they were intoxicated with alcohol was before age 15 years. A greater proportion of those who developed an alcohol problem also had a current or prior illicit drug use disorder.

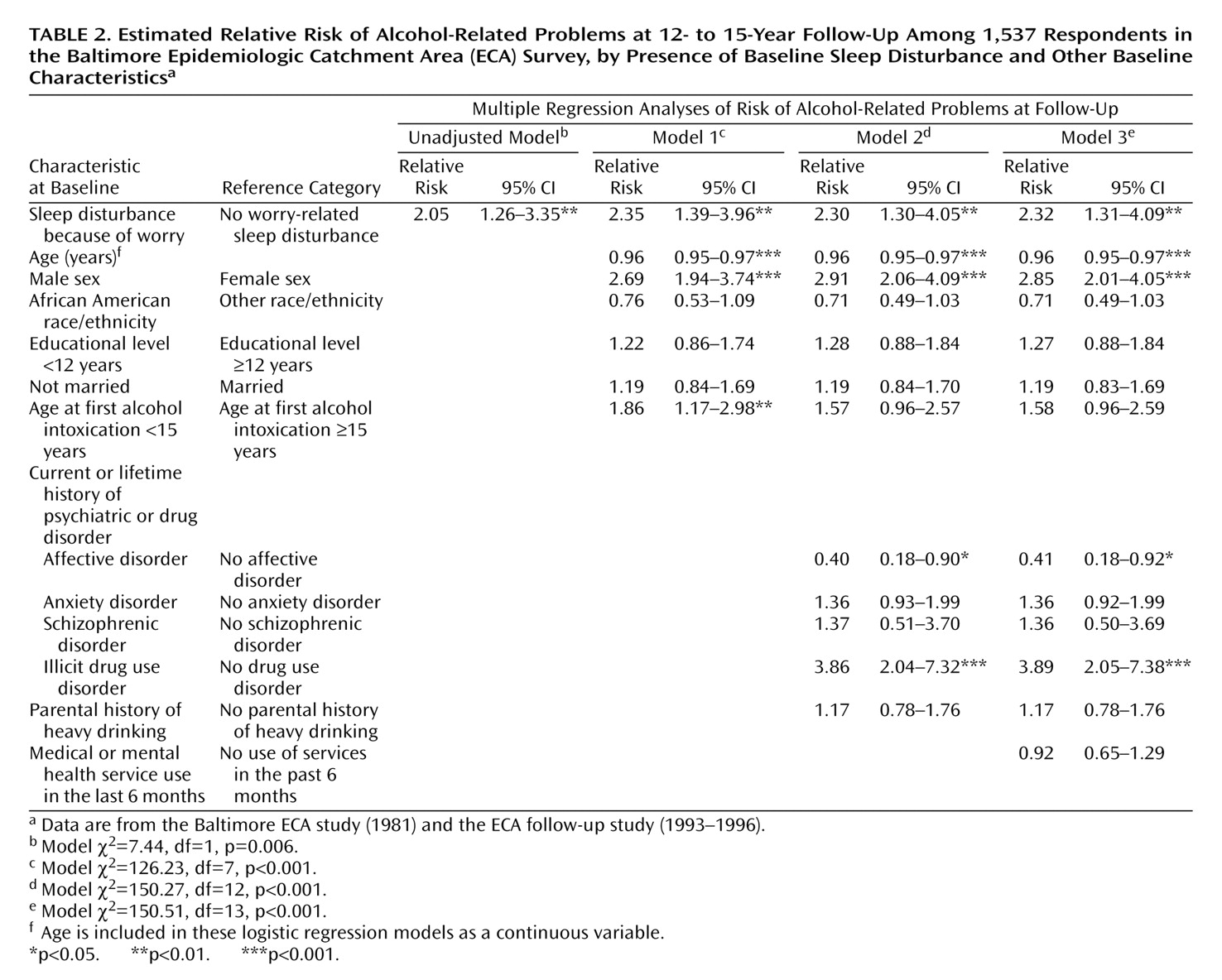

Table 2 presents the unadjusted model for estimated risk of alcohol-related problems by report of sleep disturbances because of worry, as well as three models that include adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics (Model 1); for sociodemographic, psychiatric, and substance use disorder, and parental drinking history variables (Model 2); and for health services use (Model 3). The initial estimate for risk of alcohol-related problems was twofold higher for respondents with sleep disturbances because of worry, relative to those without these sleep problems (odds ratio=2.05, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.26–3.35, p=0.004). After holding constant age, sex, race, educational level, marital status, and the age at first intoxication with alcohol, little change in the estimated relative risk for alcohol-related problems was found for those with sleep disturbances relative to those without these disturbances. Similarly, the addition of variables to control for current or prior psychiatric or substance use history and for the use of medical or mental health services did not appreciably alter the estimated relative risk for problem drinking (odds ratio=2.32, 95% CI=1.31–4.09, p=0.004).

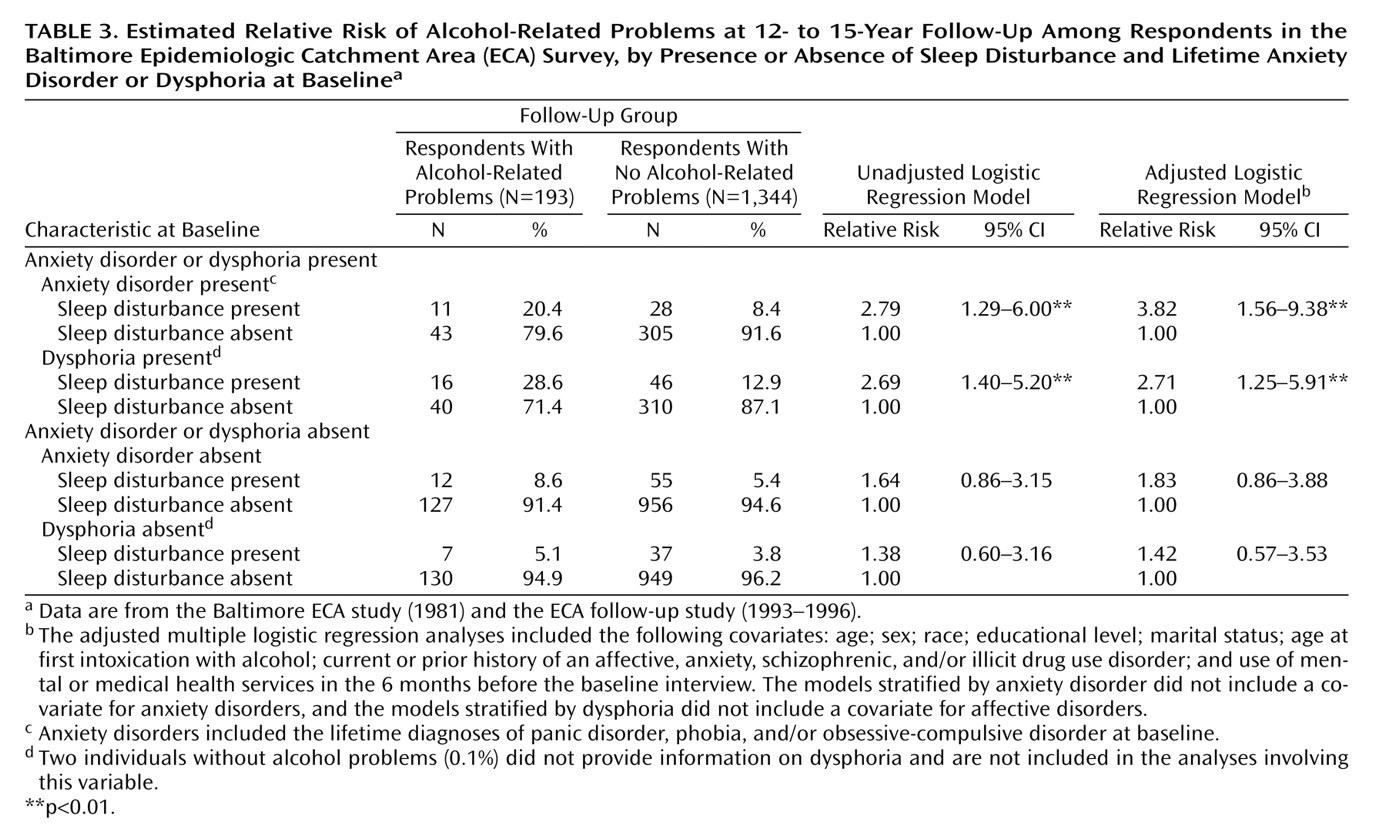

We tested for an interaction between sleep disturbances and anxiety disorders and an interaction between sleep disturbances and dysphoria and found that neither interaction was statistically significant. However, because of our interest in the potential influence of these psychological conditions, we stratified the analyses in separate logistic regression models by the presence of a report of lifetime anxiety disorders and the presence of a report of lifetime dysphoria at the time of the baseline interview (

Table 3). In the models stratified for anxiety disorder, in which the effects of age, sex, race, educational level, marital status, history of illicit drug use, affective and schizophrenic disorders, parental drinking history, and health services use were held constant, the estimated risk of problem drinking for those with sleep disturbance was 3.82 times greater for those with a lifetime history of anxiety at baseline (95% CI=1.56–9.38, p=0.003). In contrast, sleep disturbance was not a predictor of problem drinking for those with no history of an anxiety disorder (odds ratio=1.83, 95% CI=0.86–3.88, p=0.12). Similarly, the report of a history of dysphoria modified the association found between sleep disturbances and occurrence of problem drinking. Respondents who reported lifetime dysphoria and sleep disturbance at the time of the baseline interview were 2.71 times more likely to develop problem drinking by the time of the follow-up interview (95% CI=1.25–5.91, p=0.003) after adjustment for the effects of sociodemographic characteristics, history of illicit drug use, anxiety and schizophrenic disorders, parental drinking history, and health service use. No appreciable association between sleep disturbance and risk for alcohol-related problems was found for those without a report of dysphoria at baseline (odds ratio=1.42, 95% CI=0.57–3.53, p=0.45).

To further elucidate the independent contribution of sleep disturbance because of worry, we compared the rates for development of alcohol-related problems in respondents with a lifetime history of anxiety disorders by presence of sleep disturbance. Among those with a lifetime history of an anxiety disorder, the presence of a sleep disturbance because of worry was associated with an elevated risk for alcohol-related problems, compared to the absence of sleep disturbance (28.2% versus 12.4%) (F=3.73, df=3, 1533, p<0.02). In a similar fashion, among those with lifetime dysphoria, the presence of a sleep disturbance because of worry was associated with an elevated risk for alcohol-related problems, compared to the absence of sleep disturbance (25.8% versus 11.4%) (F=3.69, df=3, 1531, p<0.02). The relatively small numbers of respondents in each group did not allow multivariate analysis.

Furthermore, although our primary aim was to assess the relationships of sleep disturbance related to worry or distress, in supplemental analyses we also examined the reports of simple insomnia and hypersomnia as potential predictors of alcohol-related problems. In these supplemental analyses, we found no statistically significant association of either insomnia or hypersomnia with risk for problem drinking (data not shown).

Discussion

Because alcohol has known sedative effects, it is plausible that some individuals with sleep disturbance related to worry will use alcohol to self-medicate their sleep problems. This issue may be particularly meaningful for individuals who are not just having insomnia but are having worries that prevent them from sleeping. It may be the component of worry that prompts the use of alcohol, both to induce sleep and to alleviate the “worries” that are preventing restful sleep. It is also plausible that if this pattern becomes chronic—regardless of whether the sleep disturbances are ameliorated by the drinking—alcohol problems may develop over time. In our study, we found that individuals who reported sleep disturbances because of worry were at increased risk for developing alcohol-related problems during the interval between the baseline interview in 1981 and the follow-up interview (administered a median 12.6 years later). Because sleep disturbance related to worry may indicate an underlying anxiety or mood problem, we examined separately the data for individuals with lifetime anxiety disorders or dysphoria. We found that sleep disturbance related to worry predicted a higher risk for alcohol-related problems only among those with anxiety disorders or dysphoria at baseline. This finding suggests that these sleep problems may be related to underlying psychopathology (such as panic disorder or major depression) and that it is the psychiatric disorder that is the actual etiologic agent for the drinking problems that develop. However, individuals with lifetime anxiety disorders or dysphoria were not at increased risk for alcohol-related problems if they did not have a sleep disturbance.

The temporal relationship between these conditions may be variable and may take several different pathways. For example, sleep disturbances may lead to anxiety or mood syndromes because of sleep deprivation and reduction in daytime alertness. Individuals with depression and anxiety may be more distressed by excessive daytime fatigue or sleepiness associated with insomnia, compared to those without depression and anxiety. This daytime dysfunction may lead them more frequently to try to use alcohol to reduce their insomnia. Furthermore, insomnia has been shown to predict both depressive and anxiety disorders. Breslau et al.

(7) found that insomnia was associated with a fourfold higher risk for major depression and a twofold higher risk for anxiety disorders, relative to the absence of insomnia. Weissman et al.

(10) reported an odds ratio of 5.4 for 1-year occurrence of depression and an odds ratio of 20.3 for a 1-year occurrence of panic disorder among persons with insomnia. During a median follow-up interval of 34 years, Chang et al.

(20) found that the relative risk for clinical depression was twice as high for persons with insomnia and other sleep difficulties, relative to those without these sleep problems. In addition, sleep disturbances with anxiety or mood symptoms may act synergistically to increase risk for alcohol-related problems. A number of clinical and population-based studies have provided evidence that anxiety and affective disorders co-occur with alcohol use disorders (e.g., references

21–23).

Roehrs and colleagues

(24) specifically tested the reinforcing effects of alcohol among age-matched healthy adults with and without polysomnographically defined insomnia in a clinical trial. Both groups were offered presleep beverages (ethanol and placebo) with options for refills on two sampling nights. The researchers found that the subjects with insomnia chose ethanol more frequently and chose more ethanol refills than the subjects without insomnia. In addition, the subjects with insomnia, but not the comparison subjects without insomnia, had an increase in slow-wave sleep (stage 3–4 sleep) with alcohol administration. Alcohol was also found to influence scores on the Profile of Mood States scale.

Weissman et al.

(10) examined the odds of the first onset of alcohol abuse over a 1-year follow-up period for subjects with insomnia and no baseline psychiatric disorder, relative to those without insomnia or psychiatric diagnosis. They found that the subjects with insomnia were 2.3 times more likely to develop alcohol abuse at 1 year. As has been discussed in other assessments of incident alcohol use disorders across a relatively short interval (e.g., reference

25), it is sometimes difficult to assess whether early subclinical symptoms were in existence at the time of the baseline interview. These subclinical symptoms may influence both the report of sleep problems and the occurrence of alcohol disorders 1 year later. As a consequence, in our current analysis, we excluded the data for all individuals who reported any alcohol-related problem or met the criteria for alcohol abuse and/or dependence at the time of the baseline interview. Furthermore, the long follow-up interval in this analysis increased the likelihood that sleep problems predated the alcohol problems and not the reverse.

Several limitations in the current analyses should be mentioned. First, although we were able to hold constant several important potential confounding characteristics in the regression analyses, other risk factors such as specific personality traits, which might be associated with sleep disturbance as well as risk for alcohol problems, were not included in the analyses. Second, because of the limited size of the subgroups, we were not able to stratify the analyses by specific mood or anxiety diagnoses, such as depression or panic disorder. Third, we were not able to assess the temporal relationships between the sleep problems and the anxiety or mood symptoms because these data were not available from the baseline interview. We could not, for example, ensure that the sleep symptoms and the mood or anxiety symptoms were occurring concurrently. Fourth, the assessment of sleep disturbance related to worry was assessed by only one question. In future studies, researchers may more readily assess the relationship between sleep and alcohol use if they are provided with more details about the patterns and chronicity of the sleep disturbance as it relates to worry. Finally, we could not examine alcohol use, other psychiatric symptoms, sleep patterns, or the use of health services between the time of the baseline and follow-up interviews to better assess the potential mediating effects of anxiety and mood symptoms or of other characteristics or to assess changes in sleep and alcohol use patterns that may have occurred.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the current analyses add to our understanding of the relationship between some sleep disturbances and the development of alcohol problems. In this study we found that sleep disturbances because of worry increased the risk for alcohol-related problems but only among individuals with anxiety or mood symptoms. The findings highlight the need to increase vigilance for the assessment and treatment of sleep difficulties, particularly among those with psychiatric symptoms, because of the potential for maladaptive self-medicating behavior associated with sleep problems. Clinicians often have concerns about the treatment of sleep disorders, particularly given the widespread use of hypnotics or tranquilizers as sleep aids and the potential for long-term tolerance or dependence on these medications. However, the evaluation and treatment of sleep complaints should include a thorough assessment of underlying psychopathology (e.g., depression and anxiety) that might require a variety of treatment modalities, including psychotherapeutic as well as pharmacologic options (e.g., antidepressants). Further investigation and development of new strategies for treatment of sleep disorders are needed to improve the range of options open to clinicians. Among patients with new-onset alcohol problems, an assessment of psychopathology, including sleep disturbance, may be warranted. Furthermore, monitoring patterns of drinking behavior among patients with psychiatric disorders and/or sleep disturbance may allow identification of individuals who begin to increase their intake of alcohol in an attempt at self-treatment. Given the high prevalence of sleep problems and the relatively low frequency with which professional help is sought for these disturbances, it is important that those individuals who do make it to clinical settings have their sleep problems addressed and managed, particularly when comorbid psychopathology may be present.