The prevention of suicide and suicide attempts remains a challenge for clinicians. Suicide and suicide attempts are uncommon for individual patients in any one year, given the large at-risk population; nevertheless, about 30,000 Americans commit suicide each year

(1). It is estimated that about 5% of persons in the community have attempted suicide at least once

(2,

3). Patients with psychiatric disorders have higher lifetime rates of suicide attempt, with rates ranging as high as 29%

(3). The mortality rate because of suicide is 2%–15% in mood disorders; among mood disorder patients who have ever been hospitalized, the rate is 15%–20%

(4).

Nearly 50 prospective studies have examined risk factors for suicidal acts. In these studies, a history of suicide attempt

(5–

7), a psychiatric condition such as ongoing major depression

(8–

11), alcohol or other substance use disorder

(12,

13), hopelessness

(14–

17), separation or loss

(6,

18), anger

(19,

20), and suicidal ideation

(5,

21) have been implicated as predictors of suicidal behavior. However, although some of these studies have examined multiple risk factors, to our knowledge no prospective studies have comprehensively assessed a wide range of putative risk factors for suicidal acts, including past suicidal behavior, axis I and II psychiatric diagnoses based on a structured clinical interview, personality traits such as aggression or impulsivity, family history of suicidal behavior, and severity of psychopathology. Our group previously reported that across diagnostic categories, psychiatric patients who attempted suicide scored higher on measures of lifetime aggression and impulsivity, reported fewer reasons for living, and had more suicidal ideation and a higher subjective rating of depression severity, compared with patients who did not attempt suicide

(22). Comorbid borderline personality disorder, smoking, past substance use or alcoholism, family history of suicidal acts, traumatic brain injury, and reported childhood abuse history were more common in suicide attempters than nonattempters

(22).

We propose a stress-diathesis model of suicidal behavior based on retrospective studies of mood, psychotic, and personality disorders

(22,

23). In this model, stressors are observable precipitants for suicidal acts, including a depressive episode or life events such as financial difficulties or disruption of a relationship. The diathesis is characterized by a tendency toward pessimism and a propensity for aggression/impulsivity. Compared with nonpessimistic subjects, pessimistic subjects would tend to experience more severe suicidal ideation, to have higher subjective ratings of the severity of depression and hopelessness, and to perceive fewer reasons for living in response to an illness of comparable objective severity or to social adversity. Aggression/impulsivity may be manifested as a history of aggressive or impulsive behaviors and the presence of comorbid cluster B personality disorders. Key indicators of the presence of the diathesis would be a personal history of suicide attempt, an indication that the patient had the propensity to act on suicidal impulses in the past, and a family history of suicidal behavior, given the documented heritability of both suicidality and mood disorders

(24,

25).

To test if the presence of the diathesis predicted suicidal behavior in major depression, hypothetical risk factors for suicidal acts assessed at the time of study entry were identified on the basis of their correlation with past suicide attempts. These factors were then evaluated for their ability to predict suicidal acts in a 2-year follow-up period. We also examined the predictive effect of individual risk factors that we determined were associated with a history of suicidal acts. We hypothesized that the presence of pessimism during an acute major depressive episode but not the objective severity of depression, as well as lifelong aggressive/impulsive traits, would predict future suicidal behavior. We focused on subjects who presented with major depressive episodes, because this group has the highest risk for suicidal acts

(26). This approach may distinguish clinical characteristics that can be used at the time of patients’ presentation for treatment of a major depressive episode to identify patients at high risk for suicidal behavior.

Method

Subjects

Patients who presented for treatment of major depressive episode and who were age 18–75 years were eligible for inclusion in the study. A total of 308 patients with a DSM-III-R major mood disorder (79% with major depressive disorder and 21% with bipolar disorder) based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID)

(27) were enrolled in the study after giving written informed consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute, Columbia University, and Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic. Eighty percent of the study patients were recruited as inpatients. All patients had a physical examination and routine blood tests, including a urine toxicology screen. Exclusion criteria were current substance or alcohol abuse, neurological illness, or active medical conditions that could confound diagnosis and the clinical characterization of psychopathology. After discharge, the subjects who had been recruited as inpatients received treatment as usual in the community. Patients were evaluated after 3 months, 1 year, and 2 years. An in-depth assessment of suicidal behavior during the intervening time period was conducted by using the Columbia Suicide History Form

(28), which records self-reported data on number, method, and degree of medical damage of suicidal acts.

Instruments

Axis I disorders were evaluated with the SCID

(27), and axis II disorders were evaluated with the International Personality Disorder Examination

(29) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders

(30). Acute psychopathology during the 2 weeks before the evaluation was assessed. Objective depressive symptoms were assessed by a research clinician who used the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

(31). Patients’ subjective perception of depression severity was assessed by means of self-report with the Beck Depression Inventory

(32). The presence and severity of psychosis were evaluated in the current episode by using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)

(33), the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)

(34), and the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS)

(35). Lifetime aggression was measured with the Brown-Goodwin Aggression Scale

(36) and the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory

(37). Impulsivity was measured with the Barratt Impulsivity Scale

(38). Life stressors were measured by using the St. Paul-Ramsey Questionnaire (available from the authors), which rates the severity of individual stressors from 1 (none) to 7 (catastrophic) in six categories ranging from marital to occupational and gives a final global measure of the stressors. Hopelessness was measured with the Beck Hopelessness Scale

(39). The Reasons for Living Inventory

(40) was used to assess possible protective factors against suicide attempts. A history of childhood physical or sexual abuse and traumatic brain injury were rated as present or absent. Substance use disorders were diagnosed by using the SCID, and cigarette smoking was assessed by the subject’s report of the number of cigarettes the subject smoked per day on average over the past 3 months.

A suicide attempt was defined as a self-destructive act with some degree of intent to end one’s life. The number, method, and degree of medical damage of suicide attempts were recorded on the Columbia Suicide History Form

(28). Suicidal ideation was characterized by using the Scale for Suicide Ideation

(41). Suicide attempts were characterized by using the Suicide Intent Scale

(42) and the Lethality Rating Scale

(42), which assessed the patient’s expectation regarding the outcome of the suicidal behavior and degree of medical injury resulting from the attempt, respectively.

Statistical Method

We conducted two prospective analyses. The first analysis included all risk factors found to be associated with a past history of suicidal behavior at baseline as independent variables and was conducted to generate a list of the most significant predictors of suicidal acts. In the second analysis, we examined the role of the two diathesis traits, aggression/impulsivity and the tendency for pessimism, in the likelihood of future suicidal acts.

Analysis of clinical predictors

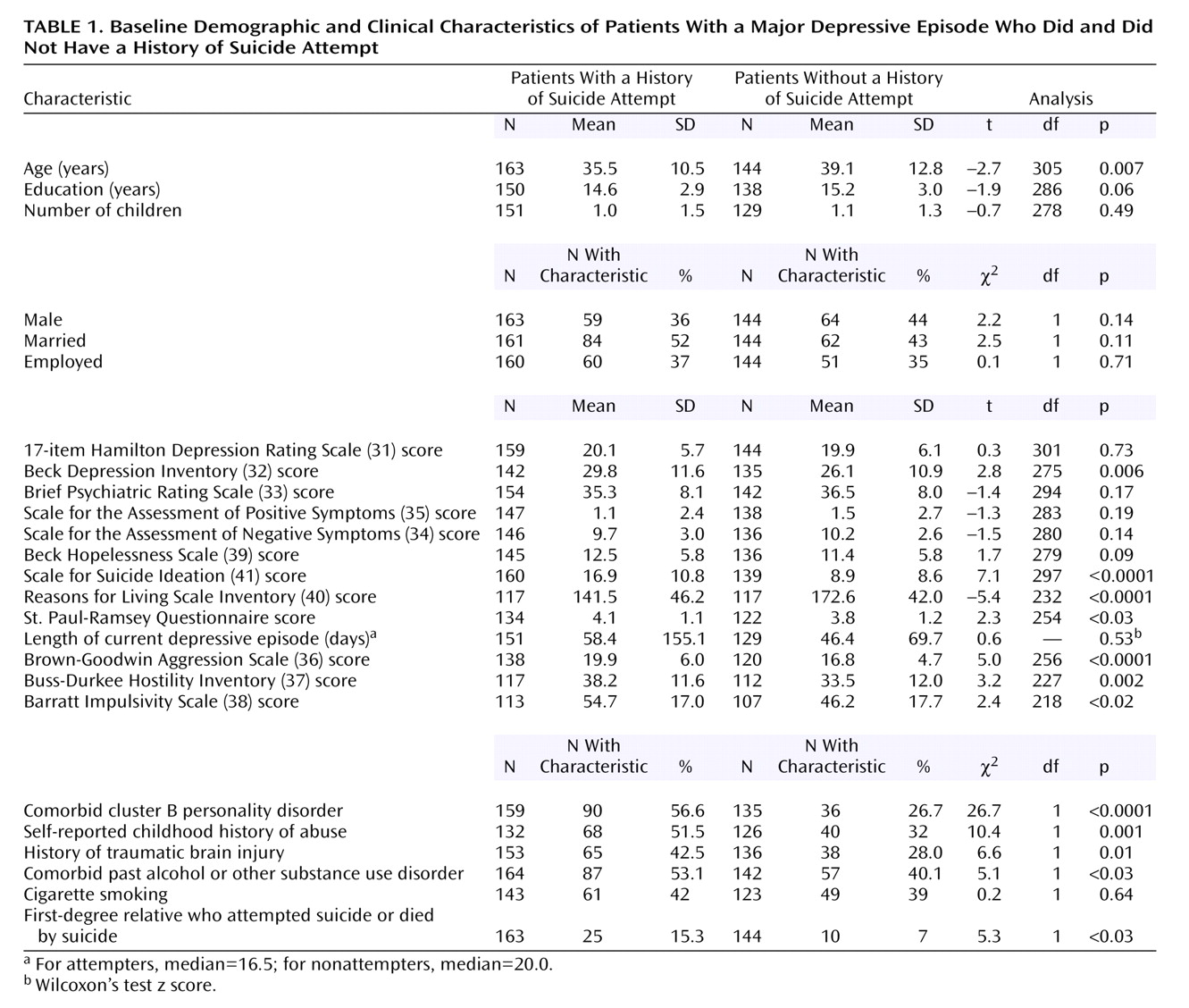

Since a history of suicide attempt is the most powerful predictor of future suicidal acts, the clinical and demographic characteristics of suicide attempters and nonattempters at baseline were compared by using two-sample t tests and chi-square tests, as appropriate. Relationships between variables were examined in this manner as well. Putative risk factors for future attempts included the variables for which significant differences between attempters and nonattempters were found at baseline and additional variables identified in the literature as risk factors for suicidal acts. The variables for which significant differences between attempters and nonattempters were found at baseline were age; presence of a cluster B personality disorder, childhood history of abuse, substance abuse, and traumatic brain injury; and scores on the Beck Depression Inventory, Scale for Suicide Ideation, Reasons for Living Inventory, Brown-Goodwin Aggression Scale, Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory, and Barratt Impulsivity Scale (

Table 1). The literature supported the addition of sex, marital status, cigarette smoking, and scores on the Hamilton depression scale, Beck Hopelessness Scale, BPRS, SANS, and SAPS. Both sets of variables were entered into a single Cox proportional hazards regression analysis to assess the relative importance of risk factors in predicting a future suicidal act. Continuous variables were dichotomized by median split to facilitate interpretation.

Analysis of diathesis and future suicidal behavior

Two factors were generated to assess the predictive power of the presence of a diathesis for suicidal acts. The first factor measured aggression/impulsivity and was previously used in work by our group

(22). This factor was produced by entering the scores from the Brown-Goodwin Aggression Scale, Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory, and the Barratt Impulsivity Scale into a principal-component analysis without rotation. The second factor, adapted from previous work by our group

(22), measured the presence of pessimism in the context of a major depressive episode. This factor was produced by entering the scores from the Beck Depression Inventory, Beck Hopelessness Scale, Scale for Suicide Ideation, and Reasons for Living Inventory into a principal-component analysis without rotation. Unlike our group’s previous retrospective study, which included several subjects with schizophrenia, the current study did not include a state factor for psychosis because the proportion of patients with psychotic symptoms in the current study was low. To facilitate the interpretation of our findings clinically, we divided the first component resulting from each principal-component analysis by the median. The median-split first components, which explained 69% and 56% of the variance for aggression/impulsivity and pessimism, respectively, could thus be interpreted as categorizing the study subjects according to high and low levels of aggression/impulsivity and high and low levels of pessimism. Subsequently, the risk of suicide or suicide attempt in the 2 years after the initial assessment was evaluated by using Cox proportional hazards regression analysis with the two factors as the independent variables. In addition, two separate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were conducted to examine the effect of obtaining high scores on each of the scales in the principal-component analyses. One regression analysis examined the role of high scores on the scales for aggression/impulsivity and the other examined the role of high scores on the scales for pessimism.

Results

Baseline Clinical Characteristics

Depressed subjects with a history of suicide attempt (baseline attempters) and those without a history of suicide attempt (baseline nonattempters) did not differ significantly in sex, education, number of children, employment status, or likelihood of being married (

Table 1). Baseline attempters, however, were significantly younger than nonattempters.

At index assessment, baseline attempters and nonattempters were similar in terms of objective severity of acute psychopathology (scores on the Hamilton depression scale, BPRS, SANS, and SAPS; length of current episode). In contrast, baseline attempters showed more pessimism, as shown by higher subjective ratings of depression severity (Beck Depression Inventory), fewer perceived reasons for living (Reasons for Living Inventory), and more suicidal ideation (Scale for Suicide Ideation) in the context of a depressive episode. Attempters and nonattempters did not differ significantly in hopelessness, as measured by the Beck Hopelessness Scale. Attempters also had higher scores on the St. Paul-Ramsey Questionnaire at baseline, but the difference in life events was not clinically meaningful (

Table 1).

Compared to baseline nonattempters, baseline attempters manifested more aggressive/impulsive traits, as reflected in higher lifetime aggression scores (scores on the Brown-Goodwin Aggression Scale and the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory), impulsivity scores (Barratt Impulsivity Scale), and rates of cluster B personality disorders (

Table 1). Attempters were more likely than nonattempters to report a childhood history of abuse, past traumatic brain injury, and comorbid past alcoholism or substance use disorder. Baseline attempters were also more likely to have a first-degree relative who had attempted suicide or died by suicide.

The subjective rating of depression severity (measured by the Beck Depression Inventory) was closely related to sex, the objective rating of depression (measured with the Hamilton depression scale), and impulsivity and, like baseline attempter status, was related to suicidal ideation and reasons for living. Cigarette smoking was related to a history of alcohol or other substance use disorder (data available from the authors on request).

Prospective Clinical Predictors

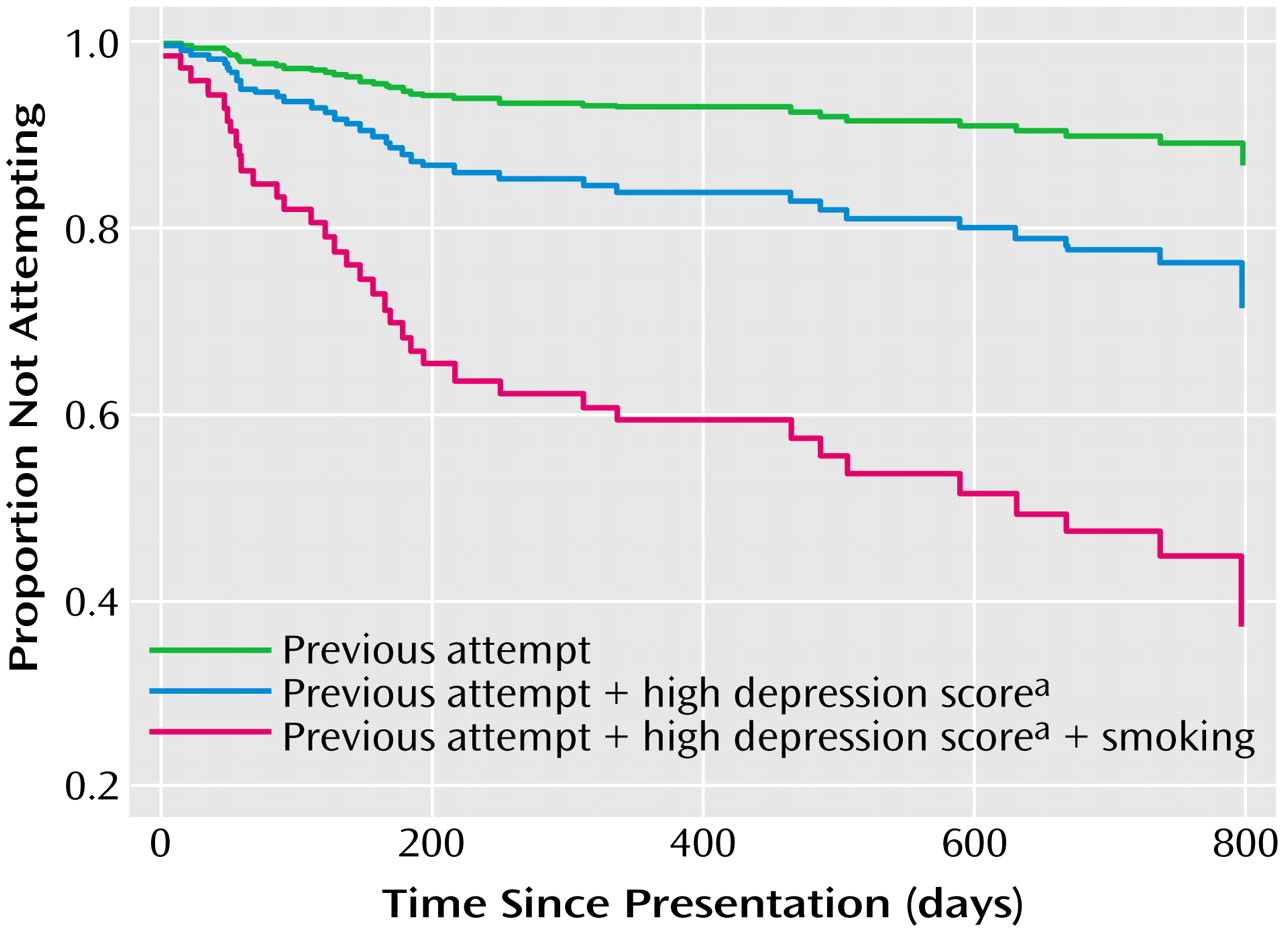

Four subjects died by suicide and 38 attempted suicide during the 2-year follow-up period. These subjects represented 14% of the study group. Most suicidal acts took place in the first year, and the rate dropped dramatically after about 3–6 months. The rate in the second year remained elevated but steady (

Figure 1).

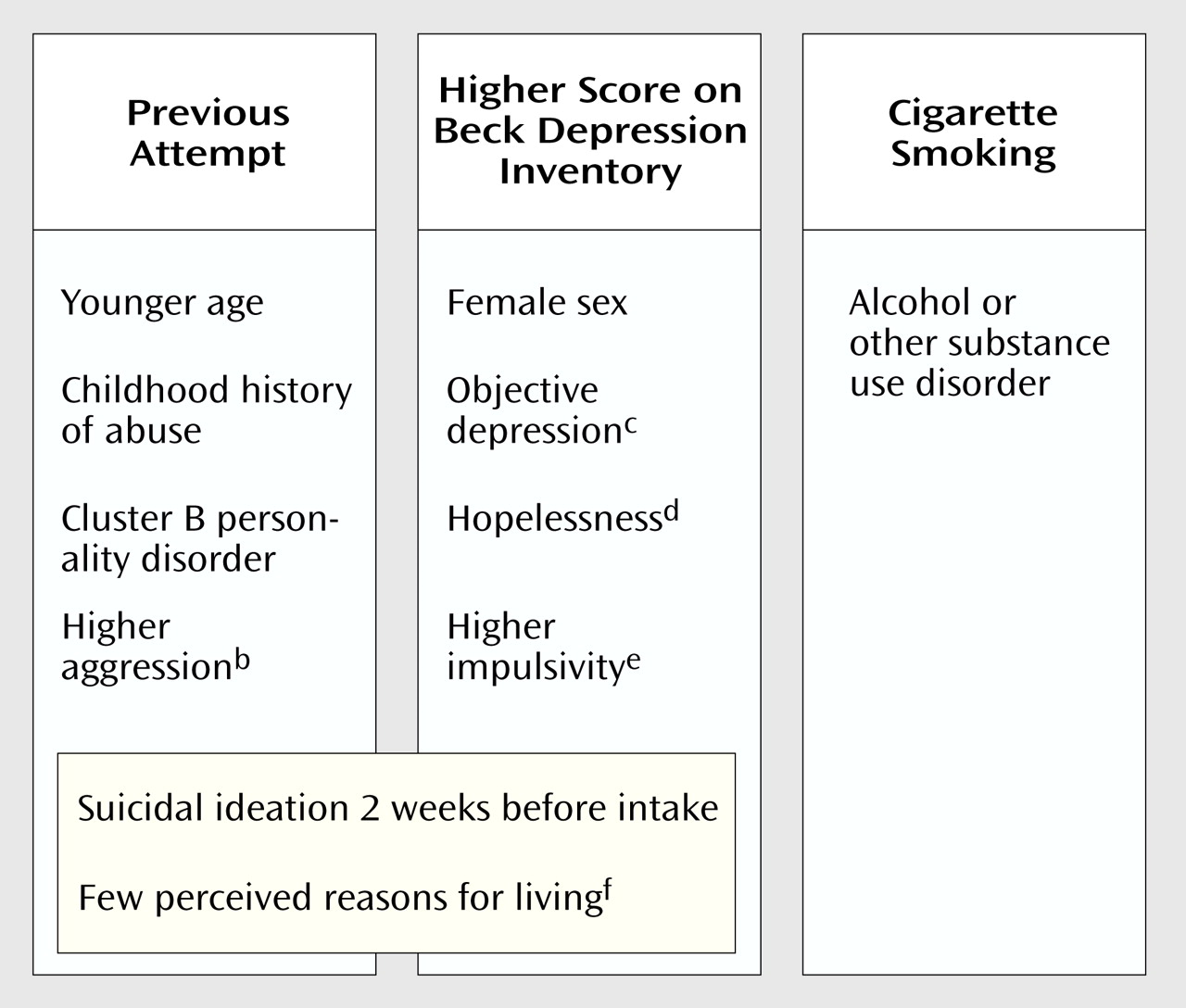

A multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis that included all correlates of past suicide attempts and additional risk factors identified from the literature showed that history of suicide attempt (hazard ratio=4.41, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.92–10.12, p<0.001), higher subjective rating of depression severity (Beck Depression Inventory) (hazard ratio=2.96, 95% CI=1.39–6.32, p=0.005), and cigarette smoking (hazard ratio=2.35, 95% CI=1.20–4.59, p=0.012) were the three strongest predictors. The effect of these predictors on risk of suicidal acts in the follow-up period was additive (

Figure 1). Chi-square tests and t tests with alpha set at 0.01 showed that the three predictors were closely related to other risk factors (

Figure 2).

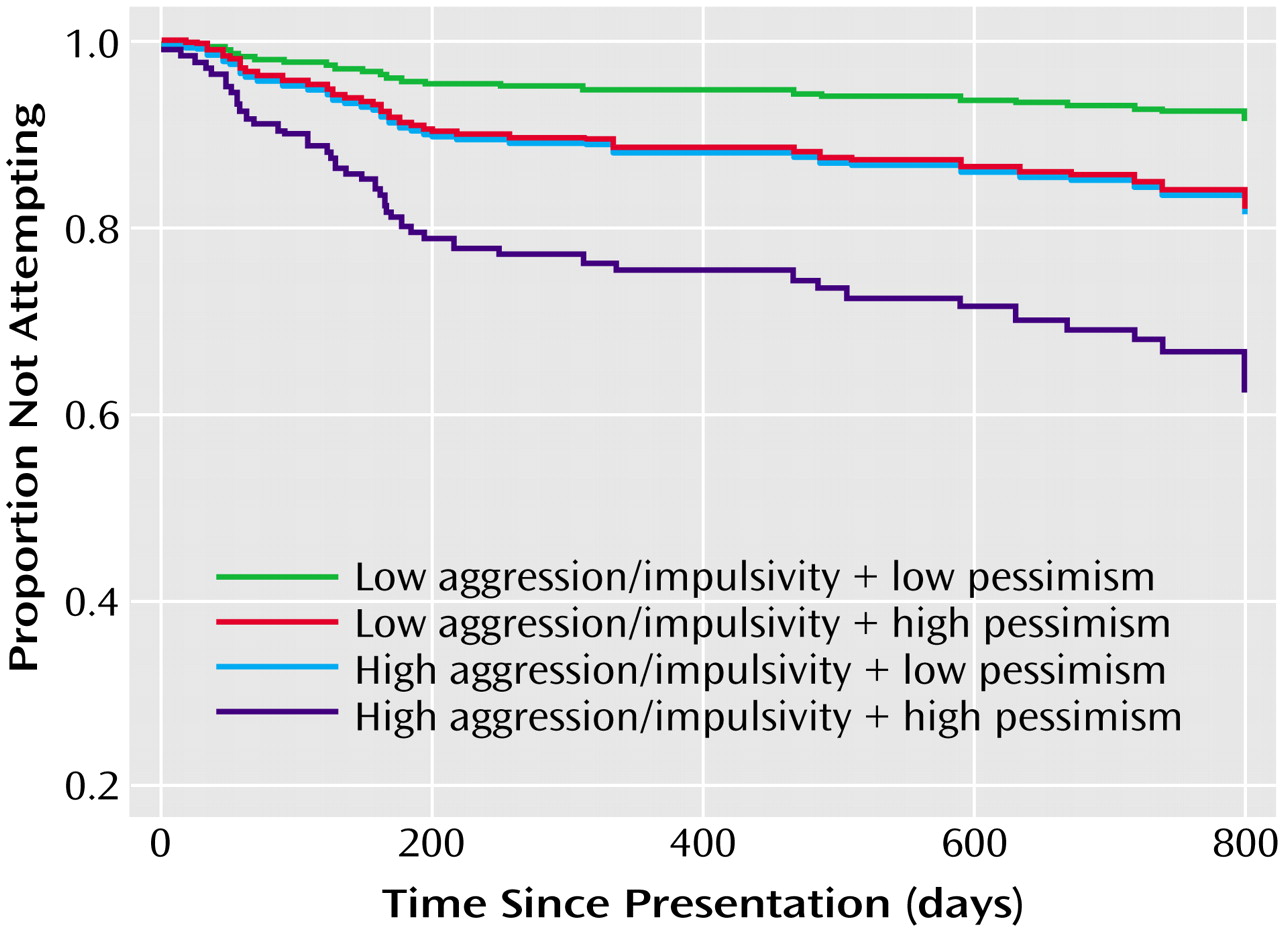

Diathesis and Future Suicidal Behavior

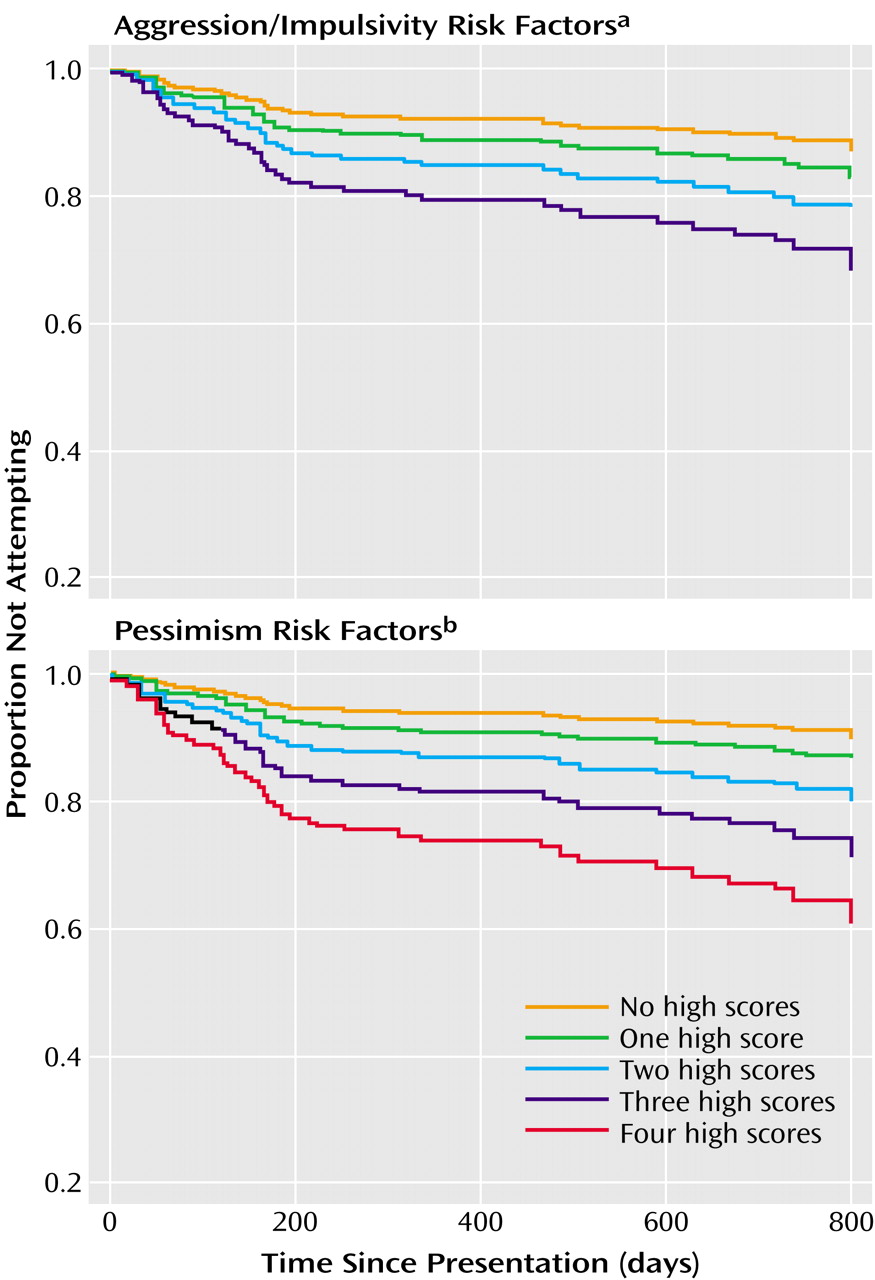

High levels of both aggression/impulsivity (odds ratio=2.26, z=2.43, p<0.02) and pessimism (odds ratio=2.32, z=2.45, p<0.02) were shown to make significant contributions to the risk for future suicidal acts (likelihood ratio test=14.8, df=2, p<0.001). In addition, the two factors were additive, i.e., a high score on either of the factors increased risk to a similar degree. When both factors had high scores, the risk for suicidal acts in the 2-year period was greater (

Figure 3). Finally, a high score on any of the scales that contributed to the aggression/impulsivity factor or the pessimism factor also appeared to increase the risk for suicidal acts (aggression/impulsivity factor: odds ratio=1.34, z=2.02, p<0.05; pessimism factor: odds ratio=1.38, z=1.92, p=0.06), although the risk associated with the aggregate pessimism factor did not reach statistical significance (

Figure 4). Thus, the presence of a diathesis clearly increases risk for future suicidal acts.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that the three strongest predictors of suicidal acts among patients with major depression in a 2-year follow-up period are history of suicide attempt, subjective rating of depression severity, and cigarette smoking. Each of these variables increased risk two- to fourfold. Furthermore, the data support our model, which posits that suicide attempters can be distinguished from nonattempters not by severity of illness as measured by a clinician but rather by a propensity to react with more subjective distress or pessimism to similar stressors and/or by displaying more aggressive/impulsive tendencies. The presence of both of these vulnerabilities appears to have an additive effect on risk.

Predictors of Future Suicidal Behavior

Past suicidal behavior

A history of suicide attempt increased the risk for future suicidal behavior more than fourfold. This finding is consistent with the findings of Nordström et al.

(7), who reported suicide rates of 15% for recent suicide attempters and 5% for nonattempters in a group of patients with mood disorders. Fawcett et al.

(5) reported that a history of suicide attempt was prospectively associated with death by suicide in patients with affective disorders. Similarly, other prospective studies have also shown that a history of suicide attempt increases the risk for subsequent attempts

(6,

43–49). Thus, a history of suicide attempt predicts future suicidal acts in the relatively brief time frame of 2 years after a major depressive episode.

Subjective rating of depression severity

The subjective rating of depression severity, as measured by the Beck Depression Inventory, predicted future suicidal acts in this study, an association also found in a retrospective study by our group

(22). It is noteworthy that in a 10-year prospective study, Beck et al.

(50) found that only the pessimism item of the Beck Depression Inventory was a significant predictor of death by suicide. This difference may be related to the fact that the outcome variable in Beck’s study was death by suicide, whereas only four of the 42 suicidal acts in our study group resulted in death.

We as well as others have shown that prior suicidal behavior does not appear to be related to objective severity of depression, as rated by assessment of observable symptoms and measured by instruments such as the Hamilton depression scale

(51–

53). These counterintuitive findings may explain why clinicians have difficulty identifying persons at risk

(22), since clinically rated psychopathology (as measured by the Hamilton depression scale, BPRS, SANS, and SAPS) is not related to future suicidal behavior. Evaluating cognitive or subjective reports of depression severity, hopelessness, and perceived reasons for living might provide clinicians with a better indication of the level of risk for suicidal behavior.

Cigarette smoking

Being a cigarette smoker increased the risk of eventual suicidal acts in this group of subjects by more than twofold. A prospective study of army recruits also showed that those who committed suicide were twice as likely to be smokers (82%), compared with recruits who died from accidents (40%) or comparison subjects (40%)

(20). The authors suggested that cigarette smokers are more likely to have a major depressive episode, antisocial personality disorder, and borderline personality disorder. All of the subjects in the current study were depressed, and in this study smoking was not associated with the presence of cluster B personality disorders but rather with alcohol or other substance use disorder. Substance use disorders are reported to increase risk for eventual suicidal behaviors

(13,

54). This effect may be mediated through pharmacologically induced disinhibition or depletion of monoamines, or it may be due to a common diathesis or to an association with relevant psychopathology such as aggression/impulsivity. Perhaps some of the predictive power of cigarette smoking stems from its association with these other risk factors. Indeed, cigarette smokers have been found to have lower serotonergic functioning than nonsmokers

(55) and more aggressive/impulsive traits

(56–

58).

Diathesis and Future Suicidal Behavior

Our results support the idea that suicidal behavior is not merely a response to a stressor. In addition, a diathesis that places the individual at higher risk for suicidal acts must be present. This diathesis, characterized by a tendency for pessimism in the context of a stressor and/or by pronounced aggressive/impulsive traits, increases the risk for future suicidal acts. Moreover, the effects of the factors are additive from two vantage points. Added risk is conveyed by high scores on each of the scales that made up the factors and by high scores on each of the factors (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). These findings suggest that each of the factors as well as their components contributes to risk for future suicidal acts, which underscores the dimensional nature of the diathesis.

Pessimism in the Prediction of Suicidal Behavior

As hypothesized, the pessimism factor, which was generated from scores on the Beck Depression Inventory, Beck Hopelessness Scale, Scale for Suicide Ideation, and Reasons for Living Inventory, predicted suicidal acts in the follow-up period. This finding is consistent with those of other prospective investigations in which more pronounced suicidal ideation was found to increase the risk of future suicidal acts

(5,

50). The presence of suicidal ideation with highly developed plans has been associated with risk of suicidal acts in epidemiologic samples as well

(2). The current study suggests that in addition to serving as a marker for imminent suicidal acts, as reflected in the clinical practice of hospitalizing or increasing the frequency of monitoring of patients with pronounced suicidal ideation, the presence of suicidal ideation indicates longer-term risk as well.

Fewer perceived reasons for living, in the context of an acute major depressive episode, were also considered part of pessimism. In this study, suicide attempters and nonattempters did not differ at baseline in number of children, marital status, and employment status, which are factors that have been postulated to be related to protection from suicidal acts (

Table 1). However, attempters had lower scores on the Reasons for Living Inventory, and their perceived reasons for living appeared unrelated to objective recent life events or signs of connection to others

(59). To our knowledge, our investigation is the first prospective study of suicidal acts to include the Reasons for Living Inventory, and the findings confirm that the association of lower scores on this scale with past suicidal acts extends to an association with future suicidal acts.

Our findings support the idea that hopelessness has some predictive power for eventual suicidal acts. However, the literature is inconsistent. Hopelessness has been reported to be a predictor of death by suicide in the long term (2–10 years) but not in the short term

(5). Yet, another prospective study of suicide attempters that followed subjects for 5–10 years found that Beck Hopelessness Scale scores were not significantly associated with eventual suicide, even though an earlier 10-year prospective study by the same group had found that the hopelessness measure was the only score that differentiated subjects with suicidal ideation who later committed suicide from those who did not

(17). In a 5-year prospective study of patients with major depression, severe hopelessness at index assessment was associated with death by suicide in the follow-up period

(15). In addition, hopelessness has been reported to be the most significant predictor of repeated parasuicide in nonpsychotic parasuicide attempters

(14). Some of these discrepancies may be attributable to differences in the characteristics of the patients included in the studies. Our study did not show hopelessness to be an independent predictor in the multivariate analysis, but the predictive role of the pessimism factor suggests that hopelessness has a role in predicting suicidal acts. Whether hopelessness is more useful in the prediction of death by suicide than in the prediction of suicide attempts and whether hopelessness is predictive of suicidal behavior beyond a 2-year follow-up period is still unknown.

We suggest that combining each of these scores into one factor may be a more robust way of ascertaining future risk for suicide, since the development of subjective distress in the face of a stressor such as a major depressive episode is likely to have multiple dimensions, including hopelessness, the cognitive experience of depression, and a perception of fewer reasons for living, as well as suicidal ideation. In addition, these results support the use of various measures of depression and despair in studies of suicidal behavior.

Impulsive and Aggressive Traits

The factor generated from the aggression/impulsivity scales (Barratt Impulsivity Scale, Brown-Goodwin Aggression Scale, and Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory) was a significant predictor of future suicidal acts. Impulsivity has been associated with a history of suicide attempt in psychiatric patients in retrospective studies

(22,

60–63). The current study supports the idea that impulsivity contributes to the risk of future suicidal behavior as well. In two previous prospective studies that considered impulsivity, impulsivity was identified as one of a cluster of factors that contributed to long-term risk for suicide

(16) and as a predictor of suicide attempts but not of death by suicide

(64). Impulsivity may influence the likelihood of suicidal acts, but it is likely to have a more complex effect on lethality of suicidal attempts. We previously reported that suicide attempters who require hospitalization for treatment of the physical sequelae of their attempt are less impulsive than attempters with less lethal behavior

(65). Similarly, Baca-Garcia

(66) reported that persons who plan their attempt over a longer period of time tend to make more severely lethal attempts. It seems likely that impulsivity increases the risk of future suicidal acts but diminishes the planning required to inflict more severe physical damage.

Although suicide attempters have been documented to be more aggressive than nonattempters in studies of subjects with personality disorders

(67,

68), unipolar depression

(23), and bipolar disorder

(69) and in a study of violent offenders

(70), to our knowledge, the relationship between aggression and the prediction of suicidal acts has been examined in only one other prospective study. Consistent with our finding that aggressive behavior increases the risk of suicide attempts in the follow-up period, Angst and Clayton

(20) reported that army recruits who later died by suicide or accident were more aggressive than comparison subjects. In a group of male students followed for 8 years, the presence of anger at oneself predicted future suicidal ideation

(19), perhaps an early sign of increased risk for future suicidal acts. Thus, the aggressive/impulsive dimension appears clearly linked to both past and future suicidal behavior.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is the inclusion of both suicide attempts and death by suicide in one outcome measure. Traits that predict suicide attempt may differ from those that predict death by suicide. Because the base rate of suicide is low even in high-risk patient populations, large groups of clinically well-characterized subjects are required to distinguish differences in predictive power for suicide attempt, compared to death by suicide. The high cost and low feasibility of such studies become critical impediments. This study focused on a high-risk population—patients admitted during a major depressive episode. Because a major depressive episode acts as a stressor within the stress-diathesis model, we were largely unable to test for the presence of the diathesis for suicidal behavior outside the immediate context of this stressor. Our study followed subjects for only 2 years. A longer-term follow-up may be of interest, given that Fawcett et al.

(5) found that short-term predictors of death by suicide differed from long-term predictors. We found that most suicide attempts occur in the first 3 months after the index evaluation, and the rate becomes lower but remains elevated for 2 years and then drops again. Fawcett et al.

(5) may have been detecting the effects of future new episodes of major depression during the follow-up period from 2 to 8 years after the initial evaluation. This later time period remains an area requiring further inquiry.

Conclusions

We found that the three most powerful predictors of future suicidal acts were a history of suicide attempt, subjective ratings of depression severity, and cigarette smoking and that each of these risk factors had an additive effect on future risk. Similarly, factor analyses revealed that a tendency toward pessimism and the presence of aggressive/impulsive traits increased future risk. These findings suggest that in addition to obtaining a history of suicidal behavior, clinicians should consider several factors in identifying patients at higher risk so that they can be monitored more closely. These factors include patients’ subjective assessment of depression severity, hopelessness, and the number of perceived reasons for living; the presence of comorbid substance use disorders, including nicotine-related disorders, and personality factors such as cluster B personality disorders; impulsivity, and aggression. Interventions such as pharmacotherapeutic prophylaxis to prevent relapse or recurrence of depressive symptoms and psychotherapeutic interventions that target pessimism may protect at-risk individuals from future suicidal behavior.