Subjects

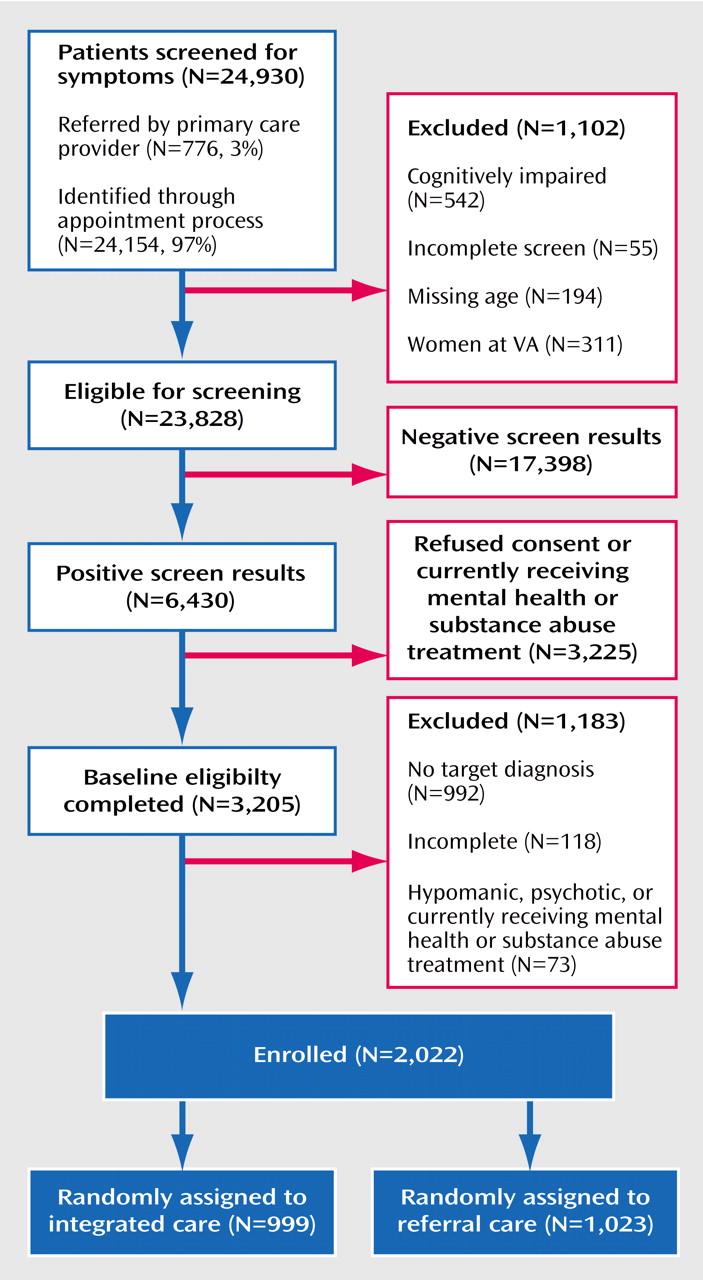

A total of 24,930 primary care patients age 65 and older were screened for a mental health disorder or at-risk drinking between March 2000 and October 2001 (

Figure 1). A positive screen was defined as significant psychological distress on the General Health Questionnaire

(12), a positive response to suicidal ideation questions modified from the PRIME-MD

(13), or at-risk alcohol consumption based on quantity/frequency criteria

(14) of more than seven drinks/week or more than two binge episodes in the past 3 months consisting of more than three drinks on a single occasion. Primary care providers also directly referred 776 patients to the study, representing 3.1% of the total sample screened.

Patients who had received mental health/substance abuse treatment in the preceding 3 months and patients with severe cognitive impairment (≥16 on the Brief Orientation Memory Concentration Test

[15]) were excluded. Primary care providers were given the opportunity to withdraw patients with positive screens for medical reasons; this occurred in fewer than 1% of patients eligible for baseline assessment. In the first stage of screening, incomplete data or cognitive impairment eliminated 1,102 patients, and 17,398 had negative screen results. Of the remaining 6,430 patients with positive screens, 3,225 elected not to proceed to a baseline assessment interview. Compared with those who consented, those who refused baseline assessment were more likely to be male (84.9% versus 74.7%) (χ

2=105.8, df=1, p<0.001) and Caucasian (72.2% versus 60.3%) (χ

2=104.9, df=1, p<0.001); have a lower mean General Health Questionnaire score (mean=3.5 [SD=3.1] versus 4.3 [SD=3.1]) (z=11.2, p<0.001), indicating less severe distress; and more reported drinks per week (mean=6.0 [SD=11.5] versus 5.1 [SD=9.8]) (z=–3.27, p=0.001).

Following the first stage of screening, 3,205 patients completed the baseline assessment for depression, anxiety, and at-risk drinking target conditions to determine eligibility for the study. Presence of target conditions was assessed by using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview

(16), Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D Scale)

(17), Beck Anxiety Inventory

(18), an alcohol quantity/frequency scale, and a detailed medication review. Additional assessments included demographic data, the Paykel Suicide Scale

(19), the Short Michigan Alcohol Screening Test—Geriatric Version

(20), and the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form

(21). Patients with a positive assessment on the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview for psychosis, mania, or hypomania were excluded (N=73). Patients with incomplete data (N=118) or no target diagnosis (N=992) were also excluded.

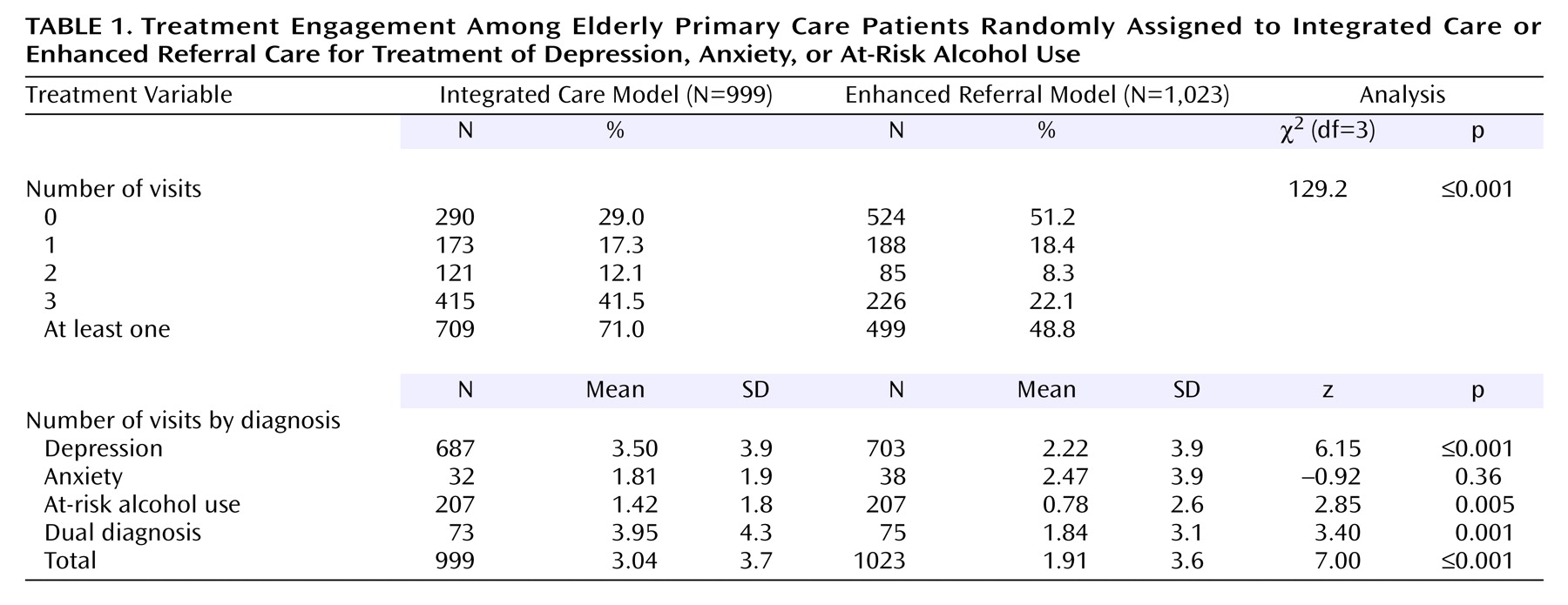

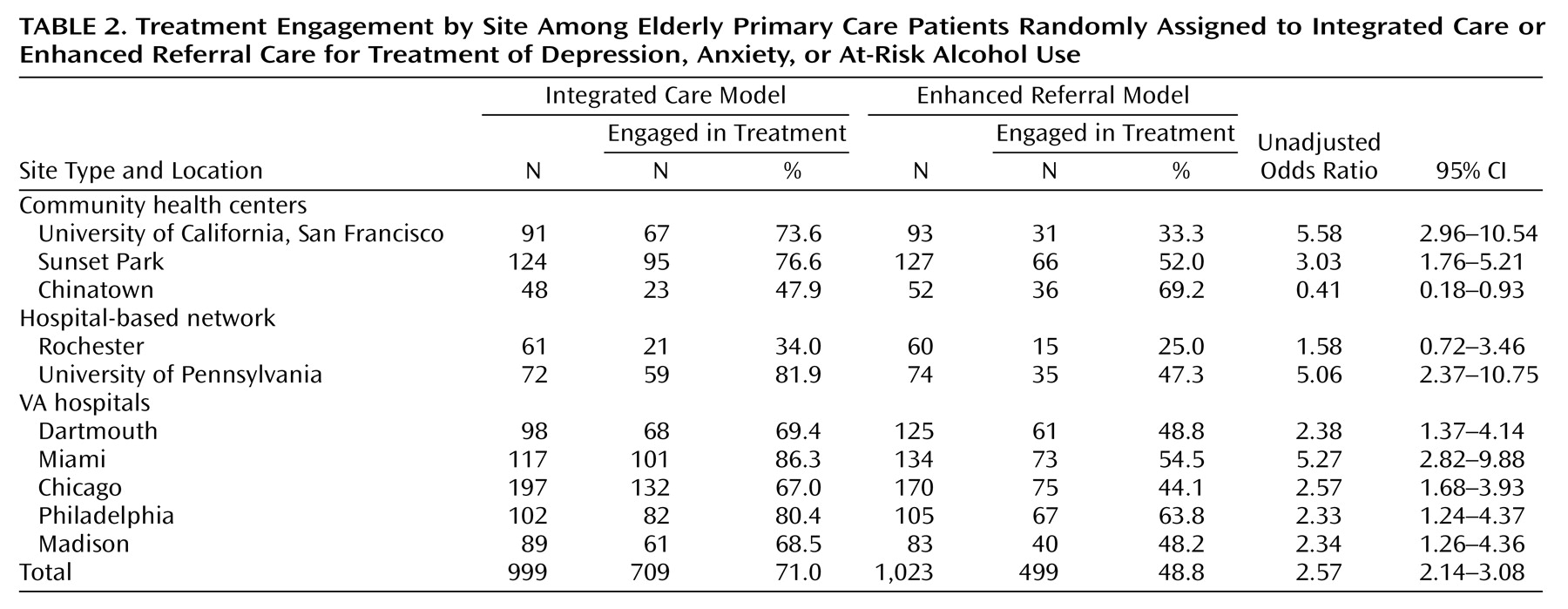

The final study group comprised 2,022 patients who met criteria, gave written informed consent after study procedures were fully explained, and were randomly assigned to receive integrated care (N=999) or enhanced referral care (N=1,023). Patients were recruited from five Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers (N=1,220 [60.3%]), three community health centers (N=535 [26.5%]), and two outpatient hospital networks (N=267 [13.2%]).

There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics between patients randomly assigned to the integrated condition and those assigned to the referral condition. Mean age of the sample was 73.5 years (SD=6.2), and almost three-quarters (N=1,498 [74.1%]) were male. Nearly half of the sample was married (N=972 [48%]), two-fifths had completed less than 12 years of schooling (N=875 [43%]), and one-fifth had limited finances as defined by “difficulty in making ends meet” (N=415 [21%]). Participants had an average of 2.8 close friends and relatives (SD=1.20). Slightly over half of the sample was Caucasian (52.0%); the next most frequent racial group was African American (24.8%), followed by Hispanic Latino (14.8%), Asian (5.6%), and other (2.9%).

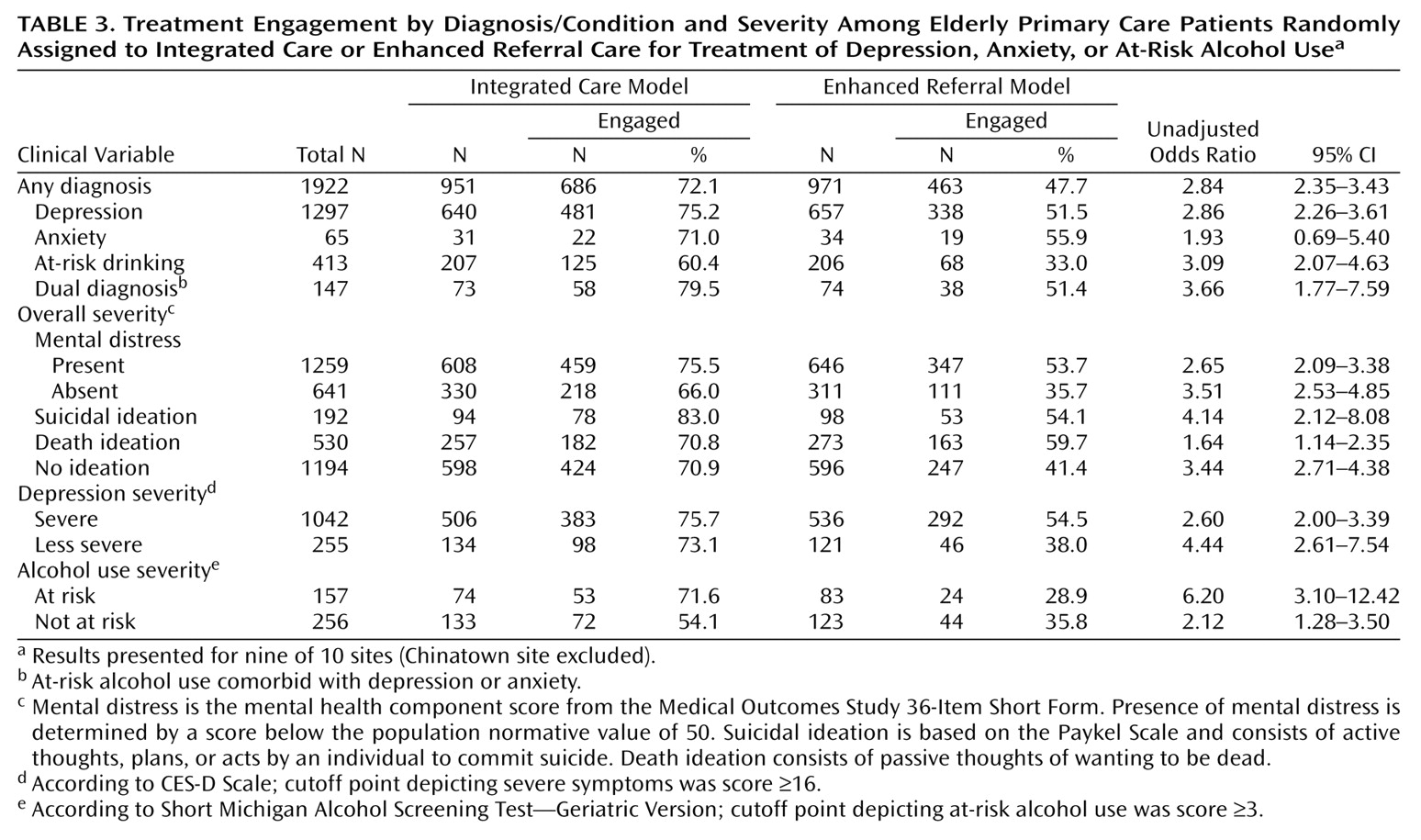

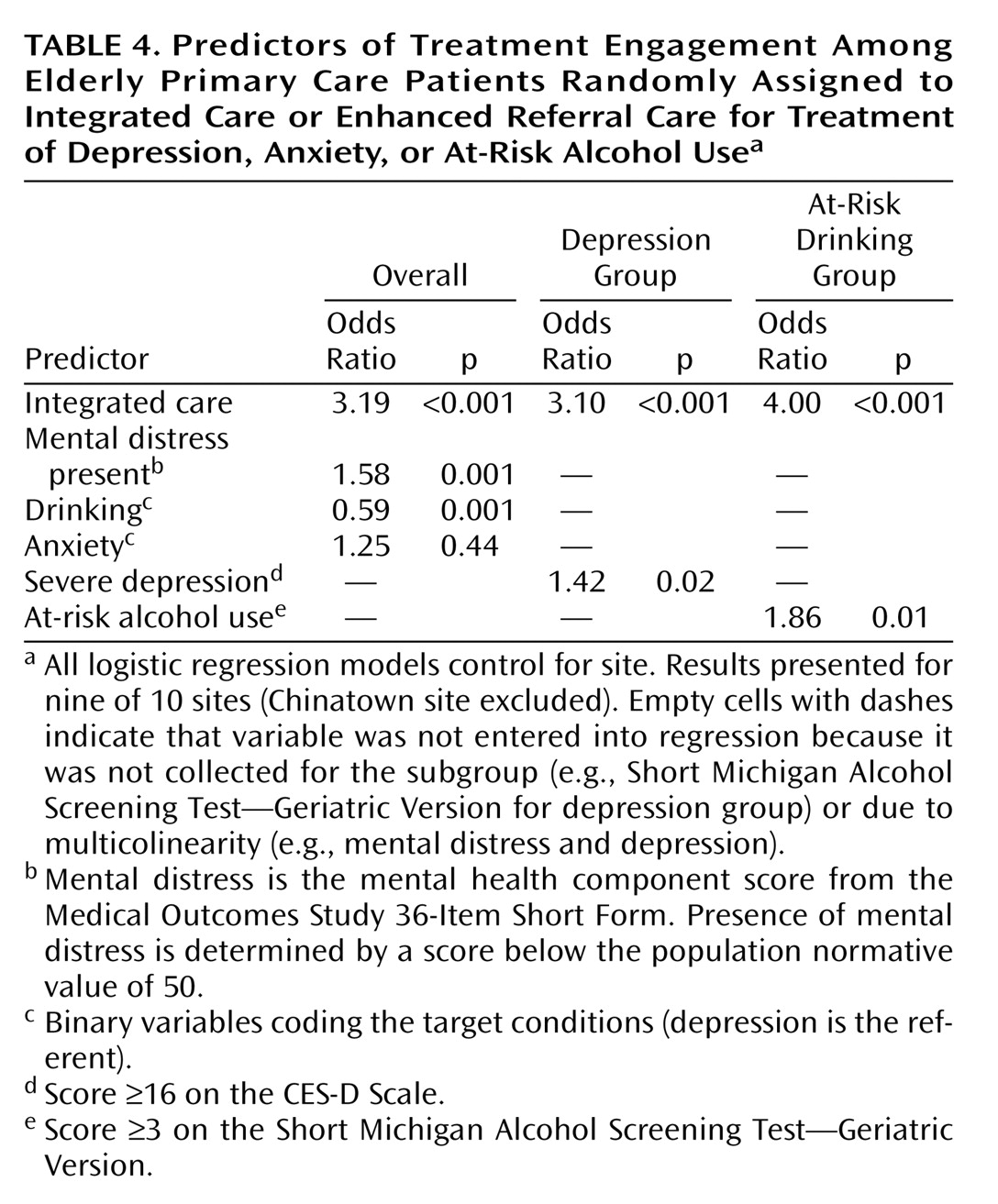

There were no between-group differences in medical or psychiatric severity as assessed with the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form, CES-D Scale, Beck Anxiety Inventory, drinks per week, or comorbid psychiatric or medical diagnoses. On average, the sample had a mean of 4.7 chronic diseases (SD=2.5) and had substantial physical and mental distress as measured by the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form (mean=39.3 [SD=10.6] and 41.9 [SD=12.9], respectively). Over two-thirds of the sample had a primary mental health diagnosis of depression (N=1,390 [69%]), one-fifth met criteria for at-risk drinking (N=414 [20%]), and the remainder were in the dual diagnosis (N=148 [7%]) or anxiety disorder (N=70 [3%]) groups. The diagnostic breakdown of the depression group was major depression (42.5%, N=591), minor depression (17.9%, N=249), dysthymia (5.5%, N=77), depression not otherwise specified (6.1%, N=85), and depression co-occurring with anxiety (27.9%, N=388). The anxiety disorders group consisted of patients with generalized anxiety disorder (75.7%, N=53), anxiety not otherwise specified (18.6%, N=13), and panic disorder (5.7%, N=4). Finally, the dual diagnosis group comprised patients with depression and at-risk drinking (64.2%, N=95); depression, anxiety, and at-risk drinking (29.7%, N=44); and anxiety and at-risk drinking (6.1%, N=9).

Study Intervention

Integrated models met the following minimum criteria for site eligibility: 1) mental health and substance abuse services co-located in the primary care setting (including assessment, care planning, counseling, case management, psychotherapy, and pharmacological treatment), with no distinction in terms of signage or clinic names; 2) mental health and substance abuse services provided by licensed mental health/substance abuse providers (including social workers, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, psychiatrists, and master’s-level counselors); 3) verbal or written communication about the clinical evaluation and treatment plan between the mental health and substance abuse clinician and primary care provider; and 4) an appointment with the mental health and substance abuse provider within 2 to 4 weeks following the primary care provider visit. Patients with at-risk drinking were offered a manualized Brief Alcohol Intervention

(22).

The minimum criteria for the enhanced referral model included 1) referral within 2 to 4 weeks of the primary care provider appointment; 2) treatment offered in a separate location by licensed mental health and substance abuse professionals; 3) agreement by the specialty mental health/substance abuse clinics to comply with model requirements, including time to first appointment and coordinated follow-up contacts if the patient failed to make the first scheduled visit; 4) assistance with transportation; and 5) facilitated direct or third-party coverage for the costs of the specialty mental health and substance abuse visit.

As anticipated, the profile of providers differed in the two models. Of the patients in the integrated model with at least one treatment visit, approximately three-fifths (60.1% [N=426]) received care from nonphysician mental health clinicians (psychologist, psychiatric social worker, psychiatric nurse, or other nonphysician provider); 35.3% (N=250) received care from a psychiatrist only or psychiatrist with a mental health clinician; and 4.2% (N=30) were treated by a primary care physician alone or primary care physician with a mental health clinician. In contrast, of the patients in the referral model with at least one treatment visit, approximately three-fifths (59.9% [N=299]) received care from a psychiatrist only or psychiatrist with a mental health clinician; 36.7% (N=183) received care from nonphysician mental health clinicians; and 3.4% (N=17) were treated by a primary care physician alone or primary care physician with a mental health clinician (χ2=71.48, df=2, p<0.001). For patients in the integrated and referral groups who received treatment following an initial evaluation (N=550 and 314, respectively), there were also modest differences in the type of treatment provided: psychotherapy only (51.6% versus 39.2%), medication management only (20.7% versus 18.2%), medication management combined with psychotherapy (21.1% versus 36.3%), and case management/evaluation (6.6% versus 6.4%) (χ2=24.65, df=3, p<0.001).

All patients were given an appointment with a mental health and substance abuse provider. The primary care physician was informed of the appointment and encouraged to support the referral. Both models were required to be in place and functioning for at least 6 months prior to patient enrollment to ensure full implementation. Model fidelity and satisfaction of minimum requirements were confirmed by the study coordinating center before randomization and systematically monitored through a detailed process evaluation for each site and through site visits.