Persistent Choreoathetosis in a Fatal Olanzapine Overdose: Drug Kinetics, Neuroimaging, and Neuropathology

Case Presentation

History

A 62-year-old married man who had a long and clear history of bipolar affective disorder with features of obsessive compulsion, Mr. A was treated by psychiatrists for more than 10 years. In his 20s he made two suicide gestures with sedatives and cut his wrist. Two years before the current admission he was hospitalized for manic behavior with psychotic features, paranoid delusions, and suicide ideation, but he had made no suicide attempts in the past 30 years. He had no history of cardiac, renal, liver, or pulmonary disease. His last physical examination, 2 months earlier, produced normal results. He regularly took olanzapine (30 mg at bedtime) and lithium (600 mg in 10 ml of syrup twice a day). Twenty years earlier he had intermittently abused alcohol and used marijuana. He was unemployed and lived with his wife, who was not aware of any recent depression or unusual behavior. They had recently taken a vacation, which he was thought to have enjoyed.Mr. A’s wife returned home from work one evening to find her husband stumbling around the house with slurred, unintelligible speech. He responded appropriately to simple verbal commands. His wife discovered the new 60-pill olanzapine bottle empty and lying on the bedroom floor. She estimated that Mr. A had taken 50 tablets, each of 15 mg (750 mg total). The lithium bottle was still full, and the containers of his other medicines (ibuprofen, terazosin, rabeprazole, methocarbamol, and thiamine) were found not to be opened or missing pills. By ambulance he was taken to the emergency room.On admission Mr. A had a temperature of 97°F, blood pressure of 134/81 mm Hg, a pulse of 125 bpm, a respiratory rate of 18 breaths/minute, and finger pulse oxygen saturation of 93%. He was confused, restless, and lethargic but was easily aroused and followed some commands. The results of a general physical examination were unremarkable. A neurologic examination demonstrated intact cranial nerves, normal symmetrical motor strength, hyperactive reflexes, and limb ataxia. Table 1 lists the laboratory findings. Blood ethanol measurement and a urine toxicology screen for opioids, amphetamines, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, cocaine, and cannabis were negative. Cerebrospinal fluid from a lumbar puncture was normal. Cranial computed tomography (CT) showed only mild age-related volume loss. The admitting diagnosis was olanzapine overdose with delirium. Mr. A was given oral charcoal and intravenous saline.

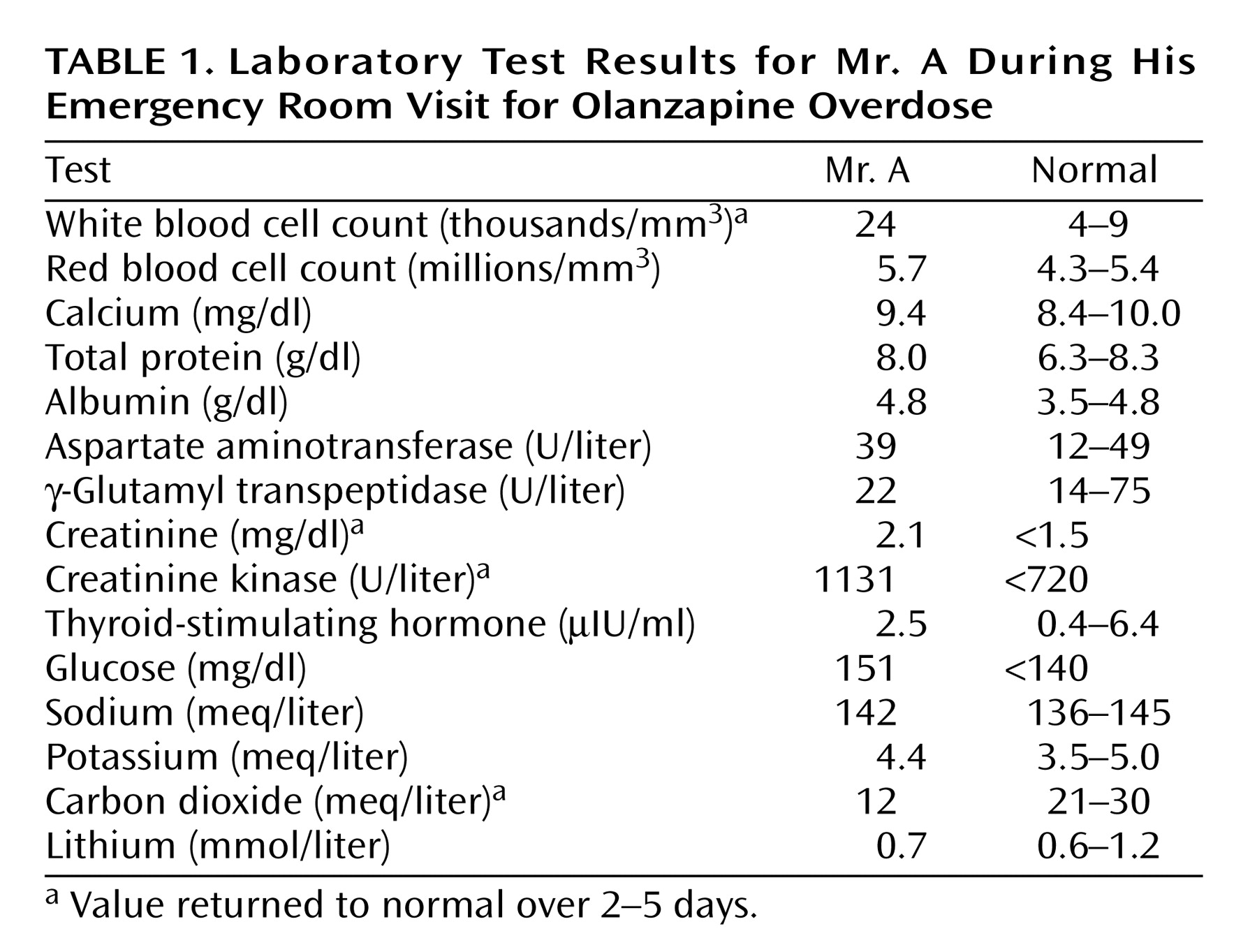

In the intensive care unit he became more lethargic and developed copious oral secretions requiring frequent mouth suctioning. He then became semicomatose and was given nasal oxygen with continuous cardiac monitoring because olanzapine overdose is associated with cardiac arrhythmias. Several hours later he developed a brief run of ventricular tachycardia followed by cardiac asystole that lasted less than 2 minutes before returning to sinus rhythm. The cardiac arrhythmia was rapidly detected, and immediate resuscitation was given. Mr. A’s oxygen saturation never fell below 90% when measured by finger pulse oximetry or by three arterial blood gas measurements that day. Transient elevations of his serum lactic acid level to 4.0 mmol/liter (normal, 0.7–2.1) and his creatinine kinase level to 5222 U/liter (normal, <720) occurred. He was intubated for airway protection from his copious secretions, but he breathed spontaneously and never required mechanical ventilation. Brief runs of atrial fibrillation were noted on the cardiac monitor for several days.On day 3 Mr. A remained semicomatose. His temperature was normal and remained normal during the hospitalization. He developed periods of coarse horizontal nystagmus beating to the right that increased over hours until they were continuous. No limb movements suggestive of a generalized seizure were seen. A second cranial CT on day 3 was initially interpreted as normal. Upon later reexamination, the CT showed subtle low attenuation in both putamen that was not present on the admission CT but corresponded to abnormalities seen on the later magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. An EEG demonstrated frequent small amplitude spike and wave complexes occurring everywhere throughout the tracing but with a predominance in both the frontocentral temporal and anterior temporal regions. A diagnosis of nonconvulsive status epilepticus was made, and Mr. A was given intravenous fosphenytoin (15 mg/kg). The nystagmus stopped but then intermittently returned with hippus requiring periodic administration of intravenous lorazepam (2 mg). A loading dose of intravenous valproate (3000 mg over 6 hours) was then given. The periods of nystagmus slowly subsided over several days. No seizure activity with limb movements ever was noted. A repeat EEG 10 days later showed background activity in the range of 4–6 and 6–8 Hz, poor organization, and infrequent bursts of sharp slow complexes that remained predominately frontal. No burst-suppression electrical activity was seen on any EEG. The results of a transthoracic echocardiogram were normal.Over the next 2 weeks, Mr. A’s level of consciousness improved slightly; he would open his eyes and turn his head toward voices but would not track people. His vital signs remained normal except for a few periods of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, which were treated with metoprolol. He remained intubated because of copious salivary secretions but breathed spontaneously. He had normal cranial nerve reflexes, vigorous spontaneous limb movements, and hyperreflexia with bilateral Babinski signs. Occasional myoclonic jerks independently appeared in all limbs.From week 3 until his death, Mr. A was comatose but had vigorous and frequent choreoathetosis coupled with elements of dystonia that involved his head and all limbs. He banged his limbs and head against the bed rails and developed bruises. At times his arms briefly assumed a decerebrate posture. Over the weeks a variety of medications (lorazepam, risperidone, haloperidol, benztropine, and morphine) were tried to lessen the vigor of the continuous choreoathetosis, with minimal benefit. MRI at week 6 demonstrated mild age-related cerebral atrophy and bilateral small hyperintense foci in the medial putaminis and globus pallida and left caudate head, mainly on diffusion-weighted images and slightly on T2-weighted images but not on T1-weighted images (Figure 1). Mr. A’s EEG slightly improved, with only rare spikes against a slow background activity of 4–7 Hz. A tracheostomy was performed, as he continued to produce copious oral secretions, and a gastrostomy was done for feeding. Late complications included pneumonia, sepsis, and skin infections of the bruised areas on Mr. A’s head and limbs. He remained comatose with choreoathetosis until his death on day 57 from congestive heart failure and pneumonia. An autopsy was performed 16 hours after his death.

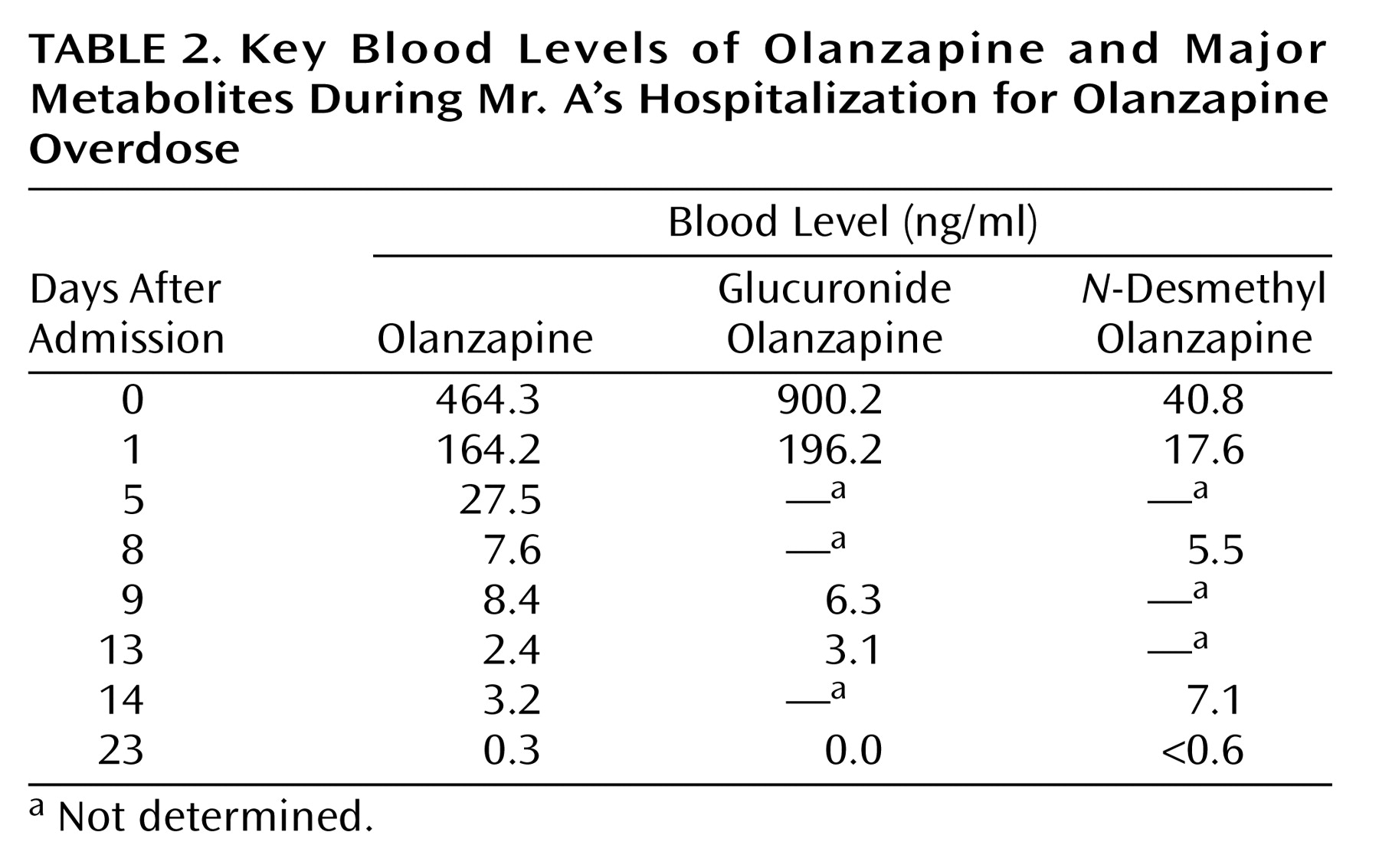

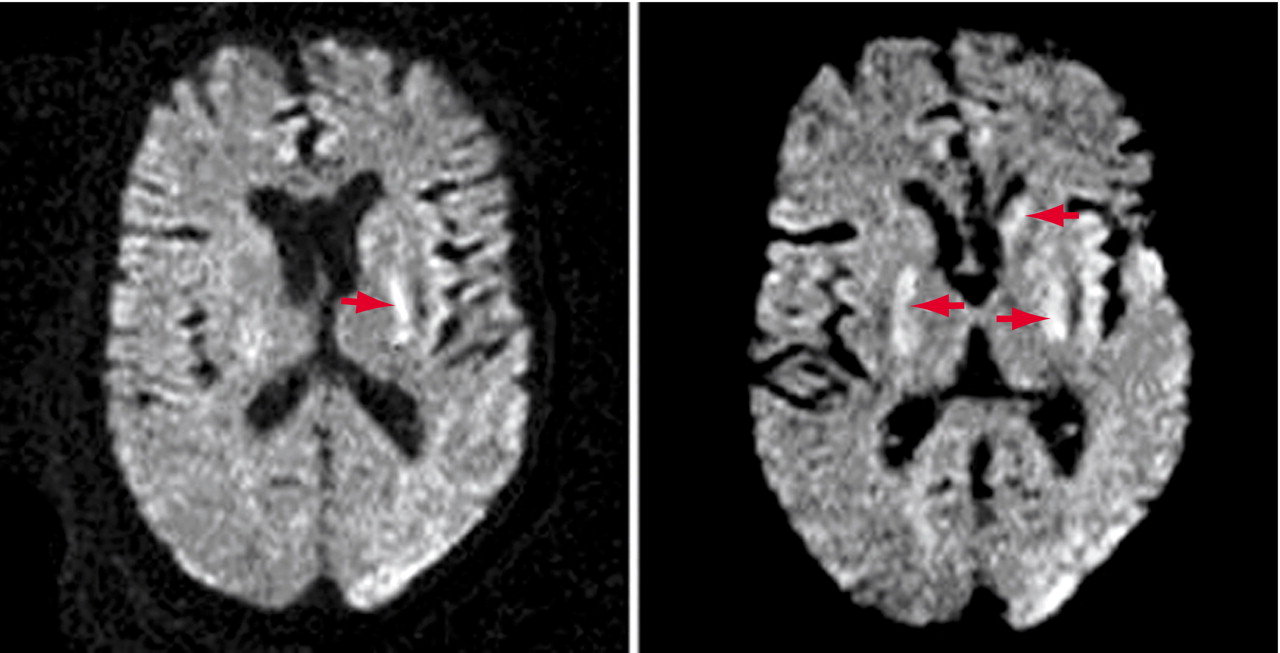

Olanzapine Drug Kinetics

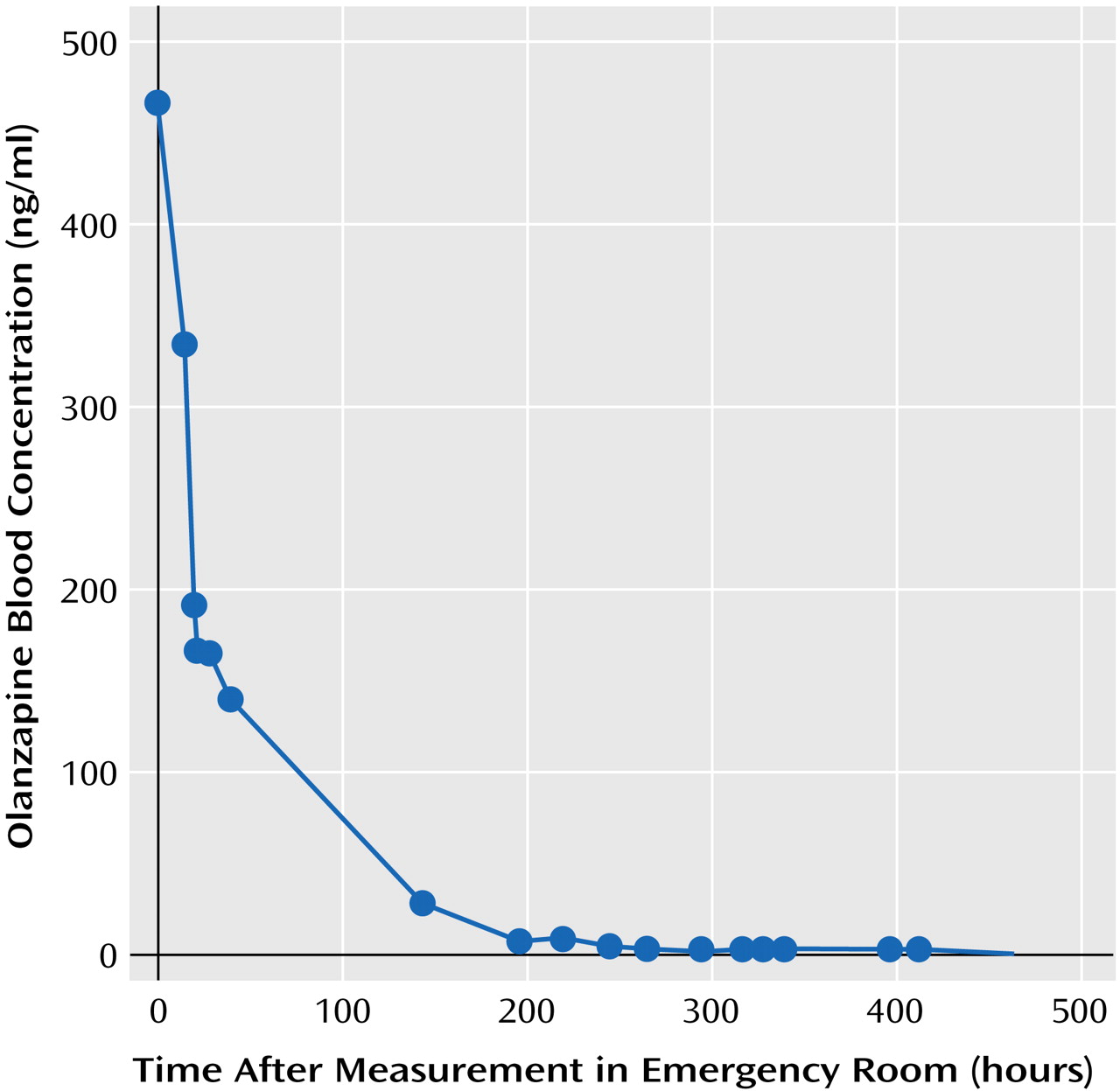

Olanzapine and olanzapine metabolites were measured since there is limited information on the human pharmacokinetics of olanzapine overdose. The plasma or sera samples were immediately frozen at –20°C after separation from red blood cells by centrifugation or after clotting. Sera, plasma, and CSF were sent frozen on dry ice to Bioanalytical Systems, West Lafayette, Ind., where the olanzapine assays were performed. A high-performance liquid chromatography method developed by the olanzapine manufacturer was used to determine the concentration of olanzapine in serum, plasma, and CSF (18). The lower and upper limits of quantitation were 0.25 and 100 ng/ml with an interday coefficient of variation of 6.49% at 0.25 ng/ml and 1.71% at 100 ng/ml. Major metabolites of olanzapine (olanzapine-10-N-glucuronide and N-desmethyl olanzapine) were measured in order to determine whether Mr. A’s drug metabolism had been unusual. The metabolite levels were measured by a method similar to that used to measure olanzapine levels. The olanzapine-10-N-glucuronide level for a sample is determined by the difference in olanzapine levels before and after acid hydrolysis. Olanzapine and N-desmethyl olanzapine levels in human plasma have been shown to be stable at –20°C for at least 90 days. The stability of olanzapine-10-N-glucuronide levels has not been tested at Bioanalytical Systems. The elimination half-life for olanzapine in blood was determined by using PK Solutions 2.0 (Summit Research Services, Montrose, Colo.).Table 2 lists key olanzapine, glucuronide olanzapine, and N-desmethyl olanzapine levels in serum and plasma by time after hospitalization, as the exact time of ingestion that day was unknown. The peak serum olanzapine level was 464.3 ng/ml, which was considerably elevated. Mr. A’s elimination half-life for olanzapine was 52.5 hours, which is similar to the 21–54 hours reported by the manufacturer for elimination of the drug at therapeutic levels (Figure 2) (3). The highest glucuronide olanzapine level was 900.2 ng/ml, and the highest N-desmethyl olanzapine level was 40.8 ng/ml.

Postmortem Findings

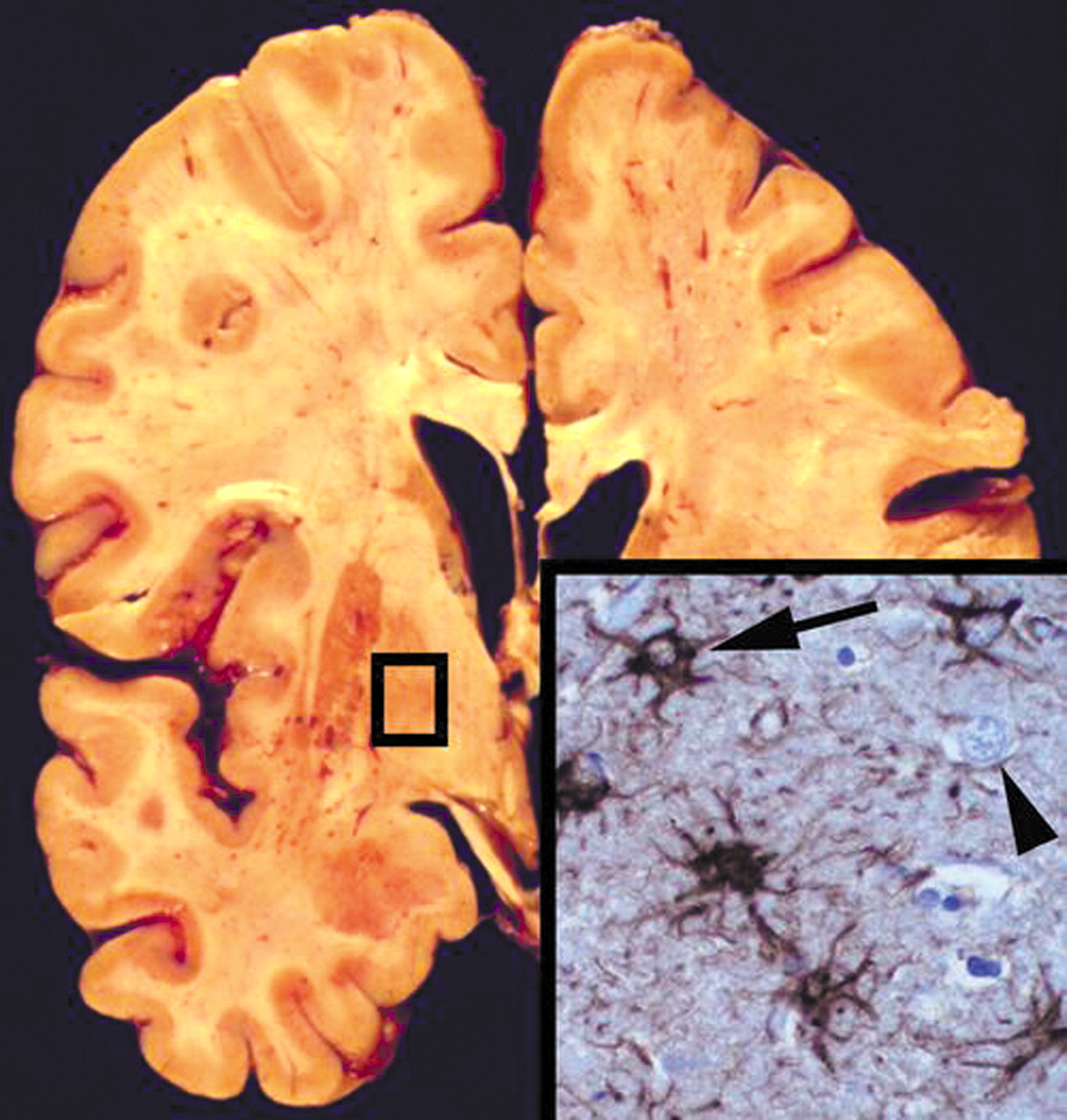

The autopsy demonstrated gross and microscopic evidence of bilateral bronchopneumonia. The other internal organs were unremarkable. The brain grossly demonstrated mild cortical atrophy and enlargement of the lateral ventricles without grossly visible lesions in the cerebral cortex, white matter, basal ganglia, brainstem, or cerebellum (Figure 3). After fixation in 10% formalin for 2 weeks, microscopic sections of the striatum, globus pallidus, and thalamus bilaterally showed extensive reactive astrogliosis with intact neuronal populations. Glial fibrillary acidic protein staining highlighted numerous stellate reactive astrocytes, confirming reactive astrocytosis (Figure 3 inset). In addition, there was patchy eosinophilic degeneration on neurons, indicative of acute terminal ischemia and nonspecific loss of the Purkinje cell layer in the cerebellum. Other brain regions were unaffected.

Discussion

Footnote

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBGet Access

Login options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).