Predictors of Research Study Enrollment

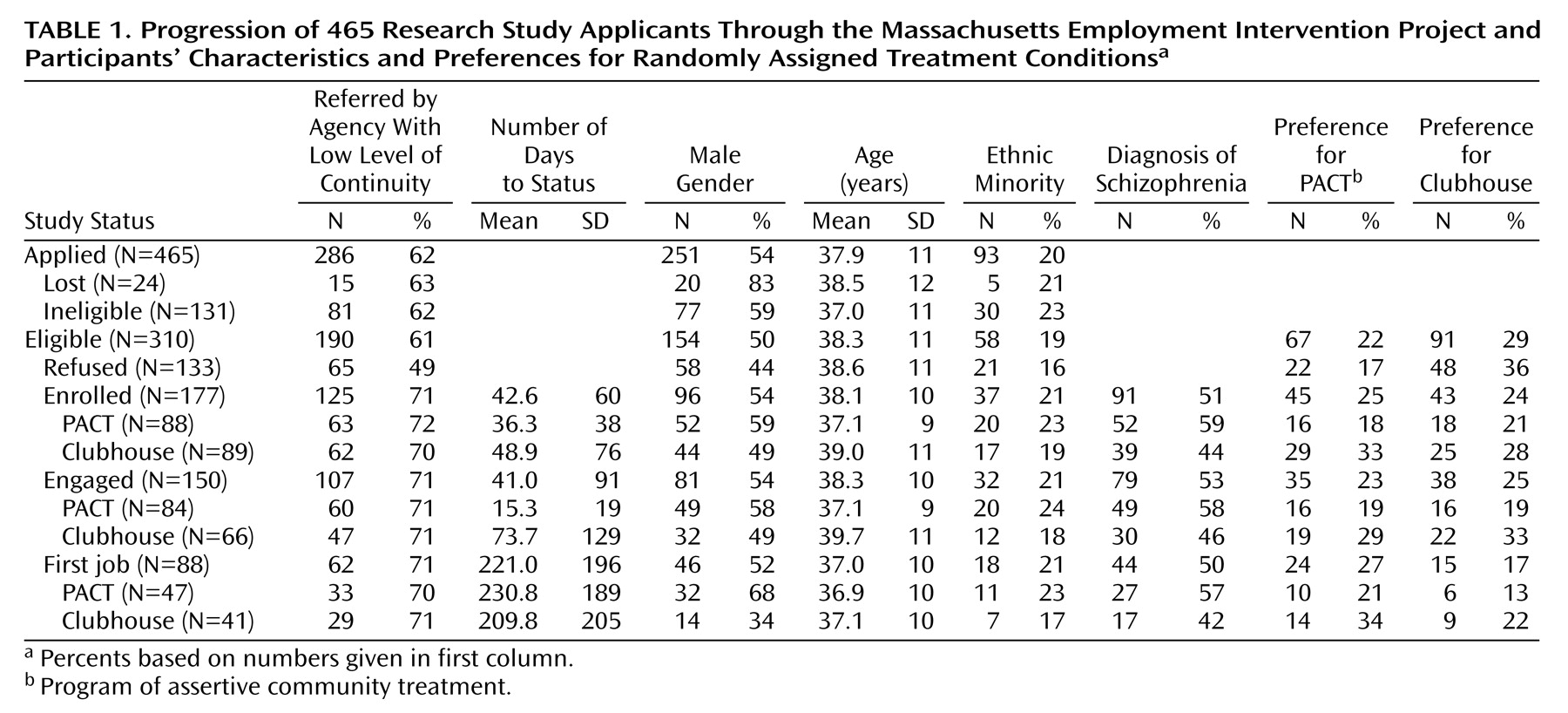

Table 1 presents an overview of participants’ progression through the research study. Study applicants who were ineligible or lost to follow-up (N=155) were more likely than eligible applicants (N=310) to be male (63% versus 50%) (χ

2=6.93, df=1, p<0.01). Otherwise, status in the project was unrelated to demographic variables.

As expected, eligible applicants referred by agencies not designed to provide continuity in outpatient care (e.g., hospitals, shelters) enrolled in the project at a higher rate than applicants referred by community mental health centers and other agencies with a high level of continuity of care (66% [N=125] versus 43% [N=52]) (χ2=15.14, df=1, p<0.001). This was true for those with a service assignment preference (65% [N=56] versus 44% [N=31]) (χ2=7.25, df=1, p<0.01) as well as for those who did not express a preference (66% [N=69] versus 43% [N=21]) (χ2=7.59, df=1, p<0.01), suggesting that the applicant’s need for outpatient psychiatric care was a primary motivation for study enrollment. There were no age, gender, or ethnicity differences between the two referral source groups.

More eligible applicants expressed a preference for clubhouse as opposed to a preference for PACT (

Table 1). Applicants preferring assignment to PACT were more likely to be female (63% [N=42]) than were applicants preferring clubhouse (52% [N=47]) or having no preference (44% [N=67]) (χ

2=6.53, df=3, p<0.05), but these three groups were comparable in age and ethnicity. Eligible applicants’ reasons for wanting to be assigned to PACT or clubhouse were often an expression of avoidance: one-third of applicants preferring assignment to PACT (31% [N=21]) simply wanted to avoid having to relinquish their current day program for the clubhouse, while about half of those preferring assignment to clubhouse (54% [N=49]) wanted to avoid relinquishing their current clinical services for PACT. Since the latter 49 applicants represented 70% of those reluctant to switch from existing services, the reluctance to switch and pro-clubhouse variables were confounded, and only reluctance to switch was included as a predictor variable in the analysis of time to project enrollment.

Almost 30% (N=133) of the applicants decided not to enroll, with an almost even split between those who did not want to risk assignment to a nonpreferred program (N=70) and those who withdrew due to fragility, lack of interest, or perceived stigma (N=63). Applicants reluctant to exchange current services for new experimental ones enrolled in the project at a lower rate (37% [N=26]) than other applicants (63% [N=151]) (χ2=14.70, df=1, p<0.001). Also, applicants who wanted to be assigned to PACT enrolled in the research project at a higher rate (67% [N=45]) than those who had no preference (59% [N=89]) or who had wanted assignment to the clubhouse (47% [N=43]) (χ2=6.50, df=2, p<0.05). This was most likely because the only way to enroll in PACT was through the research project, while the clubhouse would return to open enrollment once study recruitment was completed. Because a higher percentage of eligible applicants had been pro-clubhouse, the greater enrollment of pro-PACT applicants did not cause an imbalance. The final group of enrollees had just as many participants who preferred the clubhouse (24% [N=43]) as preferred PACT (25% [N=45]) and just as many who wanted to avoid exchanging a current day program for the clubhouse (7% [N=13]) as wanted to avoid exchanging current clinical services for PACT (7% [N=13]).

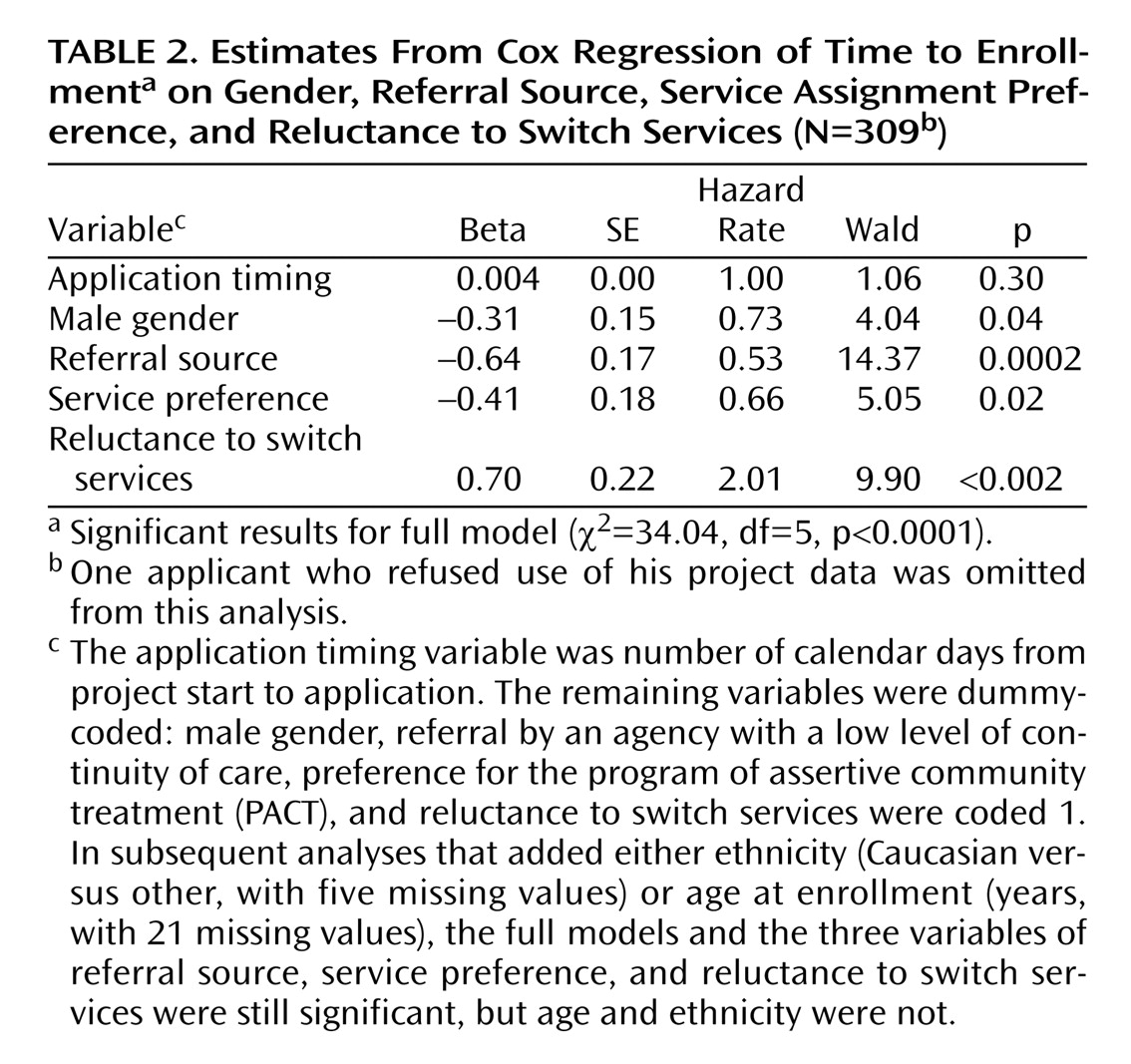

The results of a Cox regression analysis that controlled for date of application (

Table 2) confirm that applicants from agencies with a low level of continuity of outpatient care enrolled more quickly than applicants from agencies with a high level of continuity of care. Applicants who preferred assignment to PACT also enrolled faster, and those reluctant to exchange current services for new ones took longer to enroll. As the hazard rate shows, applicants reluctant to switch services were twice as likely as other applicants to withdraw their applications. These same findings are obtained when ethnicity (five missing cases) and age (21 missing cases) were added as regression model covariates.

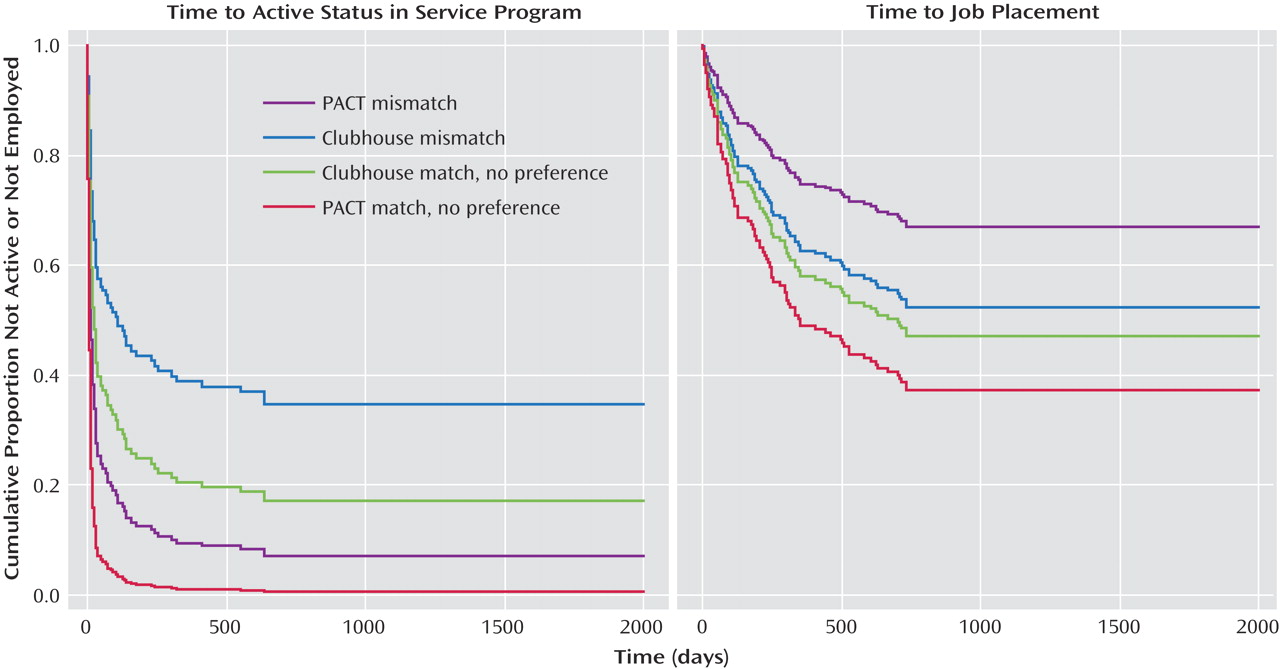

Predictors of Service Program Engagement

Applicants from agencies with a high level of continuity of outpatient care had equivalent rates of service engagement (84%) to those from agencies with a low level of continuity of care (87%), and these two groups were comparable in demographics. On the other hand, fewer enrollees who were mismatched to their service preference (75% [N=35]) became active in their assigned program compared with matched enrollees (93% [N=38]) and enrollees with no service preference (90% [N=77]) (χ2=7.69, df=2, p<0.05).

As

Table 1 shows, the clubhouse was assigned more enrollees who were matched to their service preference as well as more enrollees who had not wanted to be assigned there. That is, the clubhouse received 20% more participants than PACT who had any service preference (60% versus 40%) (χ

2=9.10, df=1, p<0.01). Fortunately, preference-matched, mismatched, and no-preference enrollees had equivalent rates of schizophrenia spectrum disorder diagnoses (52%, 51%, and 52%, respectively) and were similar in other background variables, allowing statistical control of program preference in service engagement and employment analyses.

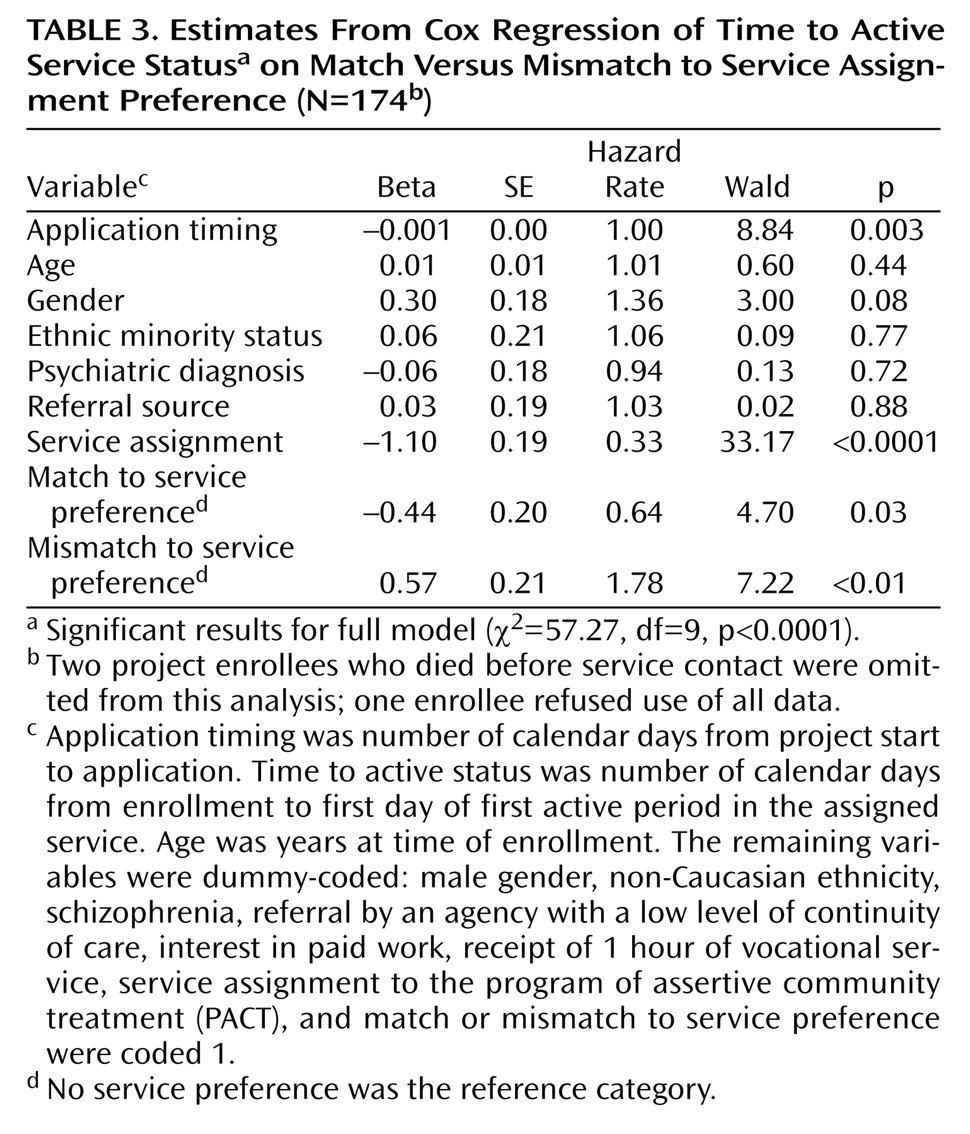

The results of a Cox regression analysis (

Table 3) show that, when we controlled for background characteristics and timing of application, enrollees mismatched to their nonpreferred program took longer to engage in services than participants with no assignment preference, while enrollees matched to their service preference became engaged faster. The interaction between program and mismatch to preference and the interaction between program and match to preference were not significant when included in the analysis, and significant main effects for match and mismatch held for both programs. When entered as a separate block, match and mismatch significantly improved the fit of the regression model: the difference between the –2 log likelihoods of the full versus reduced model was significant (χ

2=17.72, df=9, p<0.001).

Predictors of Competitive Employment

Univariate analyses revealed no significant differences in employment rates between participants assigned to the service they wanted (46% [N=19]), those assigned to the service they did not want (43% [N=20]), and those who had no assignment preference (58% [N=49]), or between referees from agencies high (50% [N=26]) versus low (50% [N=62]) in continuity of outpatient care. Competitive employment rates were fairly comparable for PACT (55% [N=47]) and clubhouse (47% [N=41]), and participants in both programs began their first competitive job an average of 7 months after enrollment. A fourth of all employed PACT participants (26% [N=12]) and 42% of employed clubhouse participants (N=17) took their first competitive job within 90 days. Interestingly, employed PACT participants were more likely to be men (68% [N=32]), while employed clubhouse participants were more likely to be women (66% [N=27]) (χ2=10.11, df=1, p<0.01).

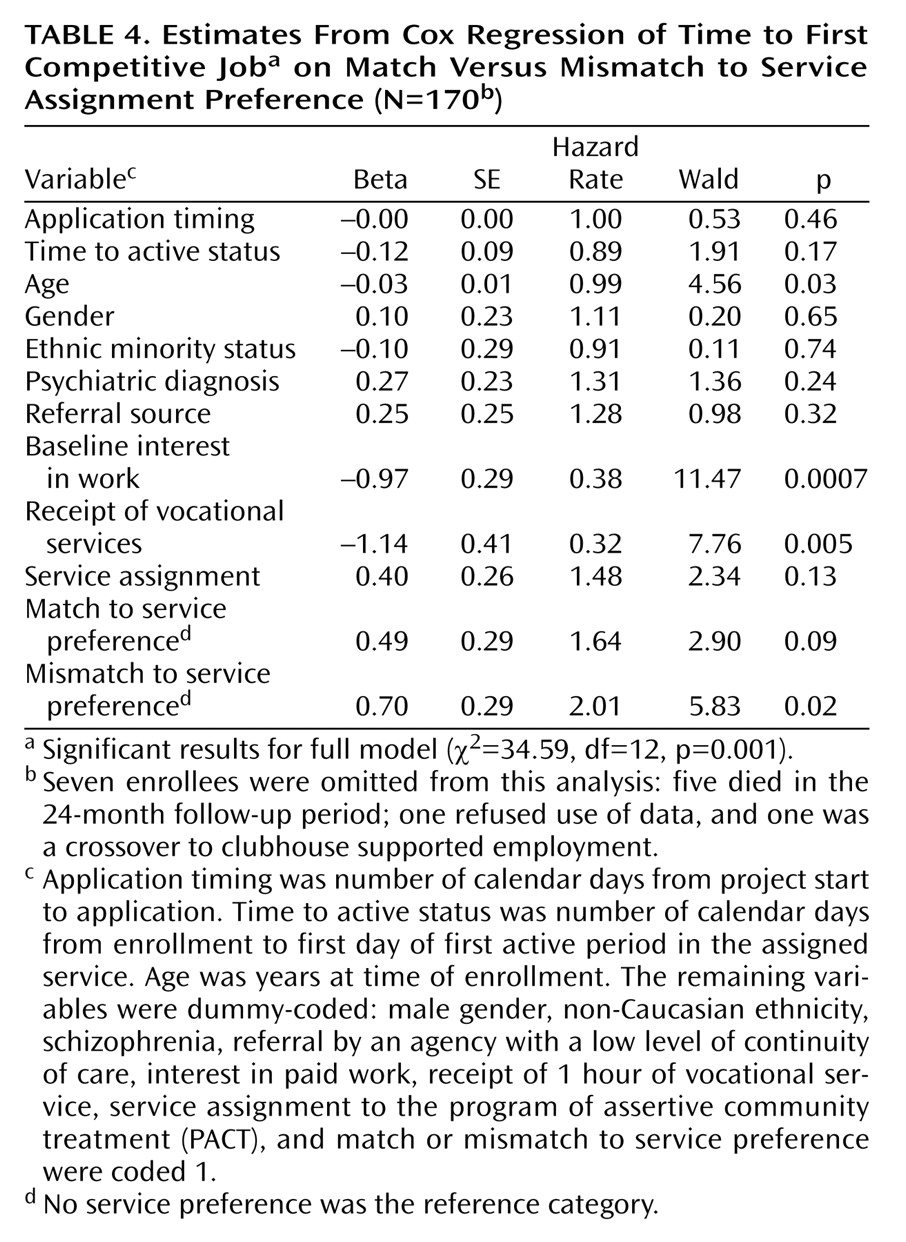

A Cox regression analysis (

Table 4) revealed a significant main effect for mismatch to service preference that parallels the main effect obtained in the Cox regression analysis of service engagement and contradicts the univariate employment findings. When we controlled for length of time to service engagement, program assignment, demographics, and two work-related background variables (baseline interest in work and receipt of at least 1 hour of vocational services), enrollees mismatched to their service preference took significantly longer to begin a competitive job than those who had no service preference. As the hazard rate shows, applicants mismatched to a service they did not want were twice as likely to never become employed as applicants with no service preference. When entered as a separate block, match and mismatch significantly improved fit of the regression model: the difference between the –2 log likelihoods of the full versus the reduced model was significant (χ

2=7.12, df=12, p<0.05). Positive main effects were also obtained for interest in work and receipt of vocational services, in keeping with earlier published findings

(26). All covariate interactions were nonsignificant.