Over the last two decades, our research team has sought to identify clinical features specific to melancholia. Findings have given weight to clinically observed psychomotor disturbance, and we therefore have argued that melancholia is as much a disorder of movement as of mood

(1). The motor disturbance manifests as retardation or agitation, while cognitive processing difficulties are commonly reported and observed. The sufferer has usually lost the “light in their eyes,” and commonly describes profound enervation.

The most common pictorial image of melancholia is the copperplate image “Melencolia I” prepared by the German Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer. As seen in

Figure 1, Lady Melancholia sits contemplating objects symbolizing the arts and sciences. While there is some suggestion of psychomotor retardation (she is slumped and her left arm supports her head), the divider is held purposefully, while her eyes are bright and look upward and outward as if absorbing the luminous energy of the Muse. The image is less of melancholia and more one of “melancholy,” a temperament style that dominated Elizabethan literature and the life of the Renaissance scholar and thought to be “the basis for intellectual and imaginative accomplishments…the wellspring from which came wit, poetic creations, deep religious insights…and profound philosophical considerations”

(2, p. 99).

In recent years we have also sought to identify symptoms—as opposed to signs—that have specificity to melancholia. Diurnal mood and energy changes, as well as profound mood nonreactivity and anhedonia, appear to be useful signals but are sensitive to subjective interpretation. As a clinician, I continue to be struck by the “mechanical failure” reported by individuals during an episode of melancholia. Many describe how they cannot even get out of bed to wash, while one patient reported such profound enervation that she became unable even to reach over to her bedside table and take her antidepressant tablets. In

Darkness Visible (3), William Styron poignantly described how his depression would force him to bed, where he would lie for hours, stuporous and effectively paralyzed.

The utility of such “paralysis” has long been suggested. German authors have emphasized the

Antriebsstörungen (or inhibition of drive—the

Antrieb) and the inability of executing an intended act as fundamental features of endogenous (or melancholic) depression. Berrios

(4, p. 361) has informed us about

aboulia (a “loss, lack or impairment of the power to will or to execute what is in mind”) and with clinical application including “melancholia.” Later (p. 362) he quotes Guislain: “Patients…can experience the wish to do, but are unable to act accordingly. They want to work but cannot.”

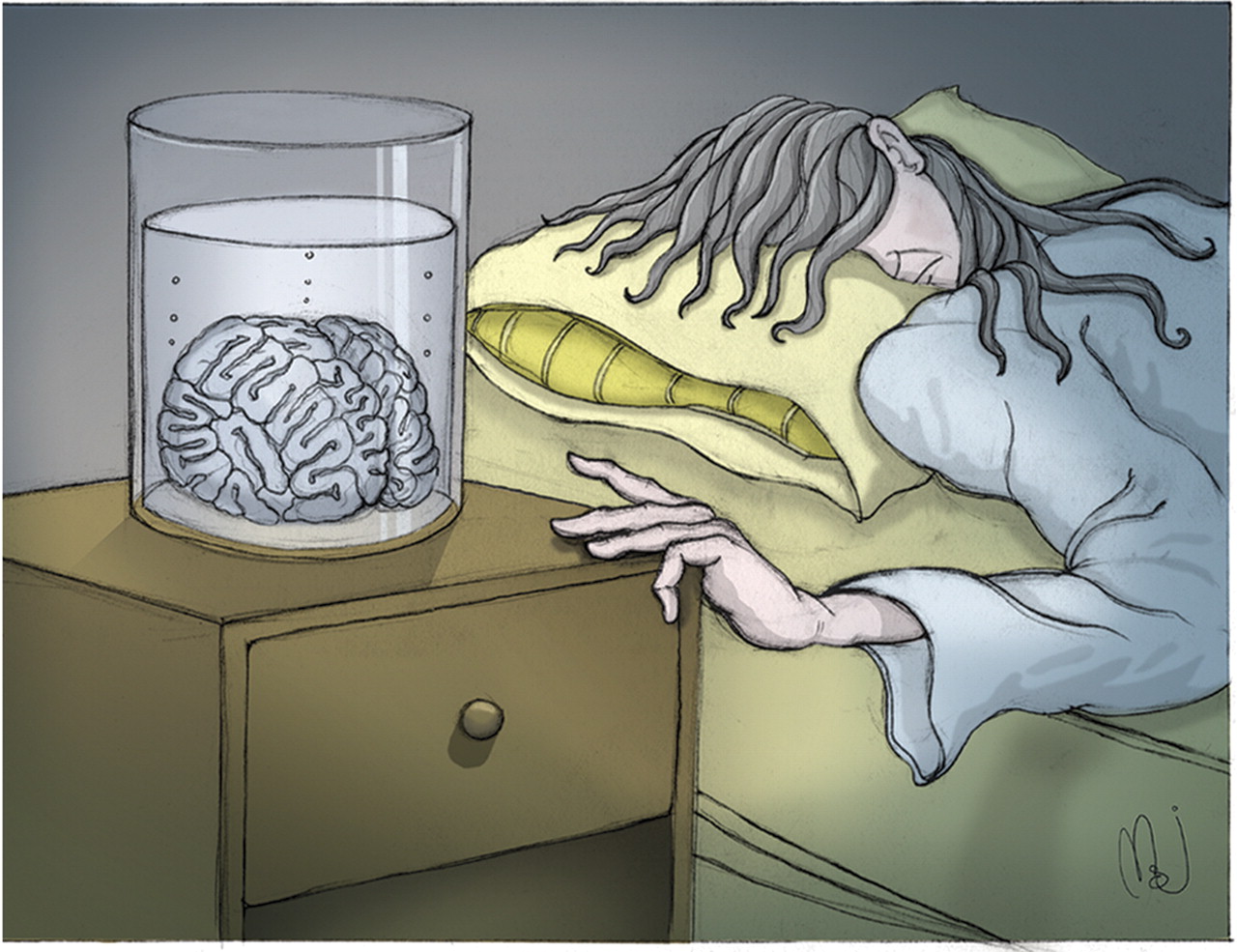

Thus, any “image” of melancholia is required to capture the physical debilitation that accompanies the melancholic mood state. Matthew Johnstone, who has long worked in the creative advertising industry in America and Australia, has sought to visually articulate a number of components to melancholic depression, with his

Figure 2 capturing the paralyzing enervation of will and function. In comparison to the Dürer image, it is divorced of any romantic appeal and more precisely captures the physical malfunctioning integral to melancholia—the key clinical signal.