For adults with bipolar disorder, research has begun to delineate a neuropsychological and social-cognitive profile characterized by deficits in verbal memory and sustained attention

(1–

6) and by differences from healthy comparison subjects in facial expression processing

(7–

11). Less is known about neuropsychological and social-cognitive features of pediatric bipolar disorder. In particular, the delineation of trait markers of vulnerability, or potential endophenotypes, for pediatric bipolar disorder could facilitate diagnosis and treatment. Neuropsychological testing provides one means for identifying such markers, which can then be studied by using neuroimaging to identify dysfunction in neural circuitry. Based on preliminary data, clinical observation, and findings in adults, two sets of cognitive skills—social cognition and response flexibility (flexible alternation between motor inhibition and execution)—represent candidate neuropsychological correlates of narrow-phenotype pediatric bipolar disorder, in which the full DSM-IV criteria for bipolar disorder are met

(12).

Social Cognition

Youths with pediatric bipolar disorder demonstrate marked social impairments

(13), despite normal social functioning before illness onset

(14). These impairments remain imprecisely characterized, however, and examination of social-cognitive skills may enhance understanding of the mechanisms underlying functional outcomes in pediatric bipolar disorder.

Children and adults with bipolar disorder perform differently from comparison subjects and individuals with other disorders on social-cognitive measures, particularly facial expression processing tasks

(7,

8,

15). Symptomatic adults with bipolar disorder also have difficulty using contextual cues to infer others’ mental states

(3). Less research has focused on expressive aspects of social cognition; clinical observation of youths with pediatric bipolar disorder, however, suggests that language pragmatics (i.e., appropriate social use of verbal/nonverbal language) may be problematic.

This pattern of aberrant social-cognitive skill suggests dysfunction in neural structures thought to mediate social, emotional, and possibly pragmatic linguistic processing

(16–

18). These structures include the ventrolateral and medial prefrontal cortices and the amygdala

(19–

21), which exhibit structural and/or functional anomalies in bipolar disorder

(22–

27).

Inhibition and Response Flexibility

Studies demonstrate differences between individuals with bipolar disorder and comparison subjects on tasks involving motor inhibition or shifting. These measures require either simple inhibition of a prepotent response or substitution of an alternate response for an inhibited behavior. Although studies using continuous performance tasks have yielded consistent findings of discrimination deficits, they have provided mixed evidence of impaired inhibition in adults with symptomatic bipolar disorder

(4,

28,

29) and no evidence of inhibitory deficits in adolescents with remitted bipolar disorder

(30).

Research regarding inhibition with alternate responding, or response flexibility, in bipolar disorder is limited. However, performance on related measures involving reward-related response reversal or attentional set-shifting showed impairment in adults

(29) and youths with bipolar disorder

(31,

32). These findings suggest diminished flexibility in response to environmental contingencies.

Converging evidence from neuroimaging and lesion studies indicates that the inferior/ventrolateral prefrontal cortices modulate both motor inhibition and execution of alternative responses

(33–

35). In light of the structural and functional aberrations observed in the ventral prefrontal cortex in individuals with bipolar disorder

(22–

27), further characterization of both inhibition and response flexibility in pediatric bipolar disorder is warranted.

We hypothesized that patients with pediatric bipolar disorder would perform more poorly than comparison subjects on social-cognitive, inhibition, and response flexibility tasks. In addition, we explored the effects on patients’ performance of current mood state and comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). As noted earlier, we were particularly interested in identifying trait-related deficits.

Results

Social Cognition

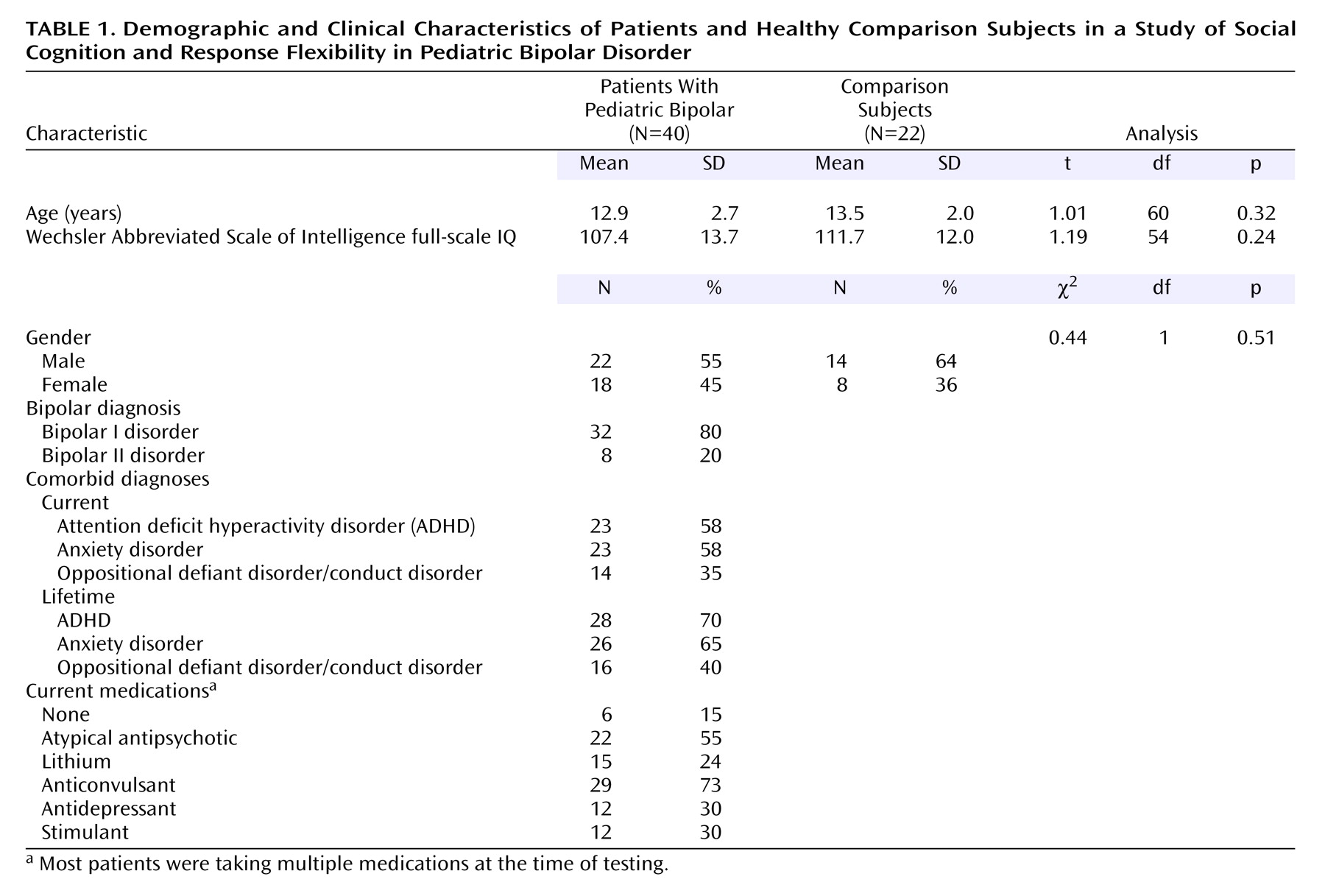

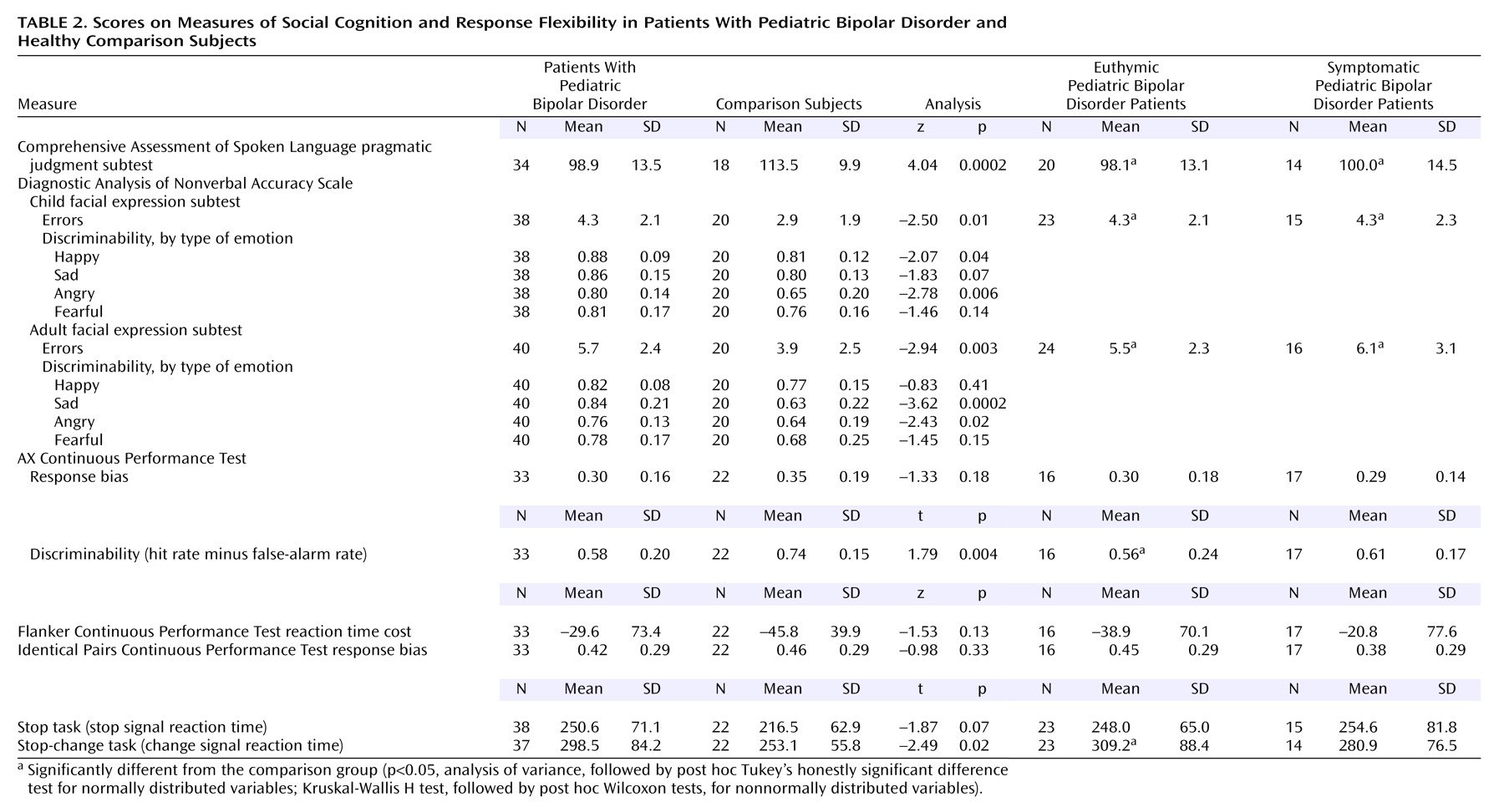

The pediatric bipolar disorder group scored significantly lower than the comparison subjects on the Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language pragmatic judgment test (p<0.001) and made significantly more errors on the Diagnostic Analysis of Nonverbal Accuracy Scale child facial expression (p=0.01) and adult facial expression (p<0.01) subtests (

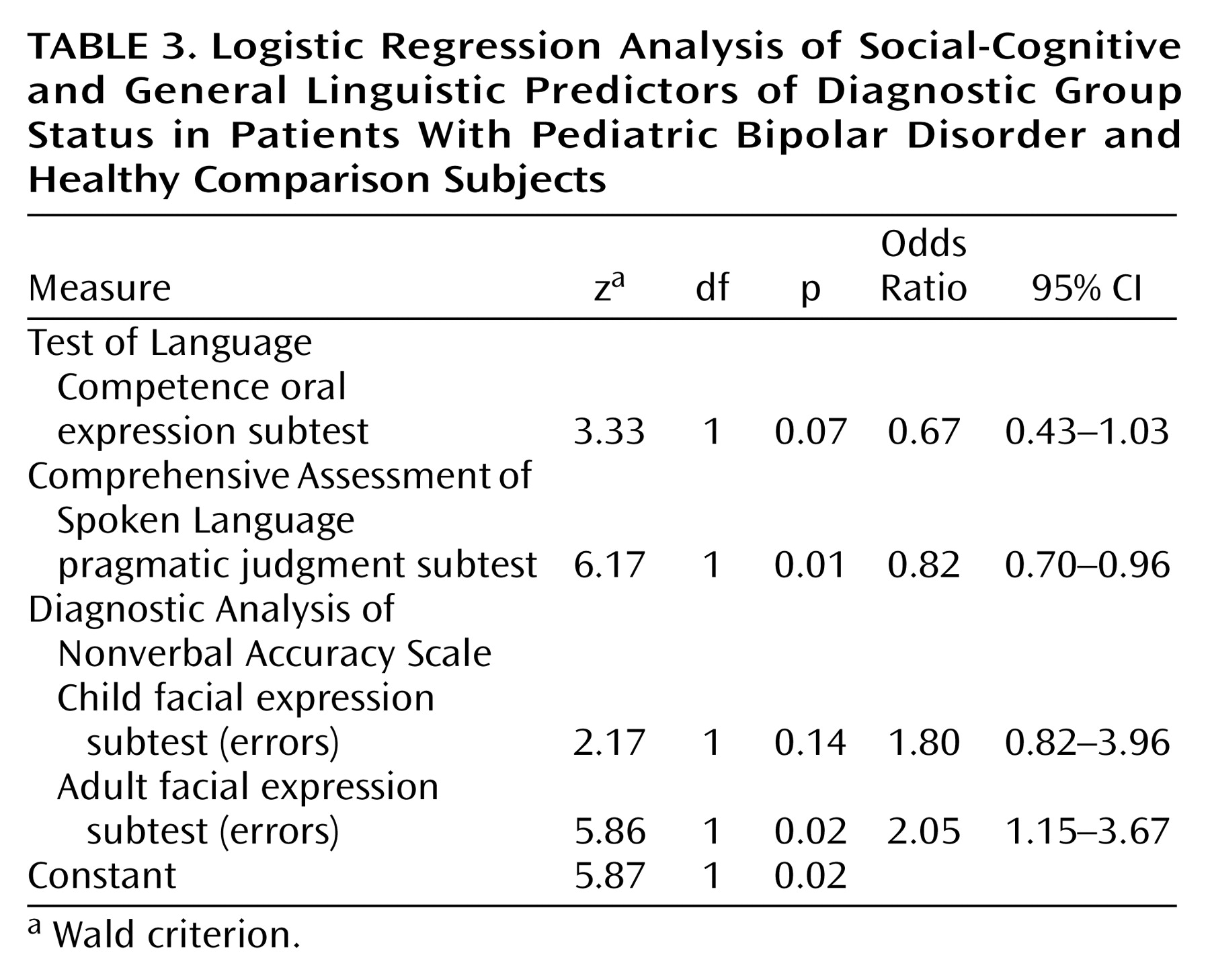

Table 2). Scores on the Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language pragmatic judgment test and the Diagnostic Analysis of Nonverbal Accuracy Scale child and adult facial expression subtests were entered into a logistic regression model predicting group membership (pediatric bipolar disorder group, comparison group). Test of Language Competence oral expression score was covaried. The predictors, as a set, reliably distinguished between youths with pediatric bipolar disorder and healthy comparison subjects (χ

2=36.6, df=4, N=49, p<0.001); 84% of the pediatric bipolar disorder group, 89% of the comparison group, and 86% of all participants were classified correctly (

Table 3). According to the Wald criterion, only the Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language pragmatic judgment score (z=6.17, p=0.01) and the Diagnostic Analysis of Nonverbal Accuracy Scale adult facial expression total errors score (z=5.86, p=0.02) reliably predicted group status.

Post hoc Mann-Whitney U tests of discriminability scores for each emotion within each Diagnostic Analysis of Nonverbal Accuracy Scale subtest indicated that youths with pediatric bipolar disorder, relative to the comparison subjects, were less sensitive to happiness (z=–2.07, p=0.04) and anger (z=–2.78, p<0.01) in children and to sadness (z=–3.62, p<0.001) and anger (z=–2.43, p=0.02) in adults (

Table 2).

Response Flexibility/Inhibition

The groups did not differ on inhibition measures, including the AX, Flanker, and Identical Pairs Continuous Performance Tests and stop signal reaction time (p>0.05) but did differ significantly on the AX Continuous Performance Test discriminability measure (p=0.004) (

Table 2). The pediatric bipolar disorder group also had a significantly longer change signal reaction time than did the comparison subjects, whether gender was covaried (p=0.03) or not (p=0.02), suggesting a deficit in response flexibility.

Post Hoc Analyses: Mood State

Social-cognitive tasks

Exploratory Kruskal-Wallis H tests comparing the healthy subjects, the euthymic pediatric bipolar disorder patients, and the symptomatic pediatric bipolar disorder patients yielded significant omnibus differences among the three groups on the Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language pragmatic judgment test score (p<0.001) and the total errors scores on the Diagnostic Analysis of Nonverbal Accuracy Scale child facial expression (p=0.02) and adult facial expression (p=0.02) subtests (

Table 2). Post hoc pairwise comparisons indicated that both pediatric bipolar disorder patient groups performed significantly more poorly than the healthy comparison subjects on all three measures (p<0.05).

Response-flexibility/inhibition tasks

Comparisons of the healthy subjects, euthymic pediatric bipolar disorder patients, and symptomatic pediatric bipolar disorder patients indicated significant omnibus differences on change signal reaction time, whether gender was covaried (p=0.05) or not (p=0.02), but not on any other motor inhibition measures (all p>0.05). Post hoc contrasts showed that only euthymic pediatric bipolar disorder patients performed more poorly than the healthy comparison subjects on change signal reaction time (gender covaried: p<0.05; no covariates: p=0.01).

Post Hoc Analyses: Comorbid Diagnoses

Exploratory comparisons indicated significant omnibus differences among the pediatric bipolar disorder patients with ADHD, the pediatric bipolar disorder patients without ADHD, and the comparison subjects on the social-cognitive measures (Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language pragmatic judgment: χ2=16.72, df=2, N=52, p<0.001; Diagnostic Analysis of Nonverbal Accuracy Scale adult facial expressions: χ2=8.92, df=2, N=60, p=0.01; Diagnostic Analysis of Nonverbal Accuracy Scale child facial expressions: χ2=6.30, df=2, N=58, p=0.04), but not on the inhibition/response flexibility measures (AX Continuous Performance Test response bias: χ2=3.31, df=2, N=55, p=0.19; Flanker Continuous Performance Test reaction time cost: χ2=3.01, df=2, N=55, p=0.21; Identical Pairs Continuous Performance Test response bias: χ2=1.58, df=2, N=55, p=0.45; stop signal reaction time: F=1.55, df=2, 59, p=0.22), except for change signal reaction time (F=3.25, df=2, 55, p<0.05, with gender covaried). Post hoc comparisons indicated that the patients with and without ADHD performed worse than the comparison subjects on all three social-cognitive measures (p<0.05 for each comparison) and that the patients without ADHD had poorer change signal reaction time scores than the comparison subjects (p<0.05). There were no significant effects of current anxiety disorder on any measure (all p>0.05).

Discussion

Results indicate deficits in social cognition and motor flexibility in patients with narrow-phenotype pediatric bipolar disorder. Relative to comparison subjects of comparable age, gender, and IQ, youths with pediatric bipolar disorder performed more poorly on tasks involving facial emotion identification and formulation of socially appropriate responses to interpersonal situations. Indeed, performance on social-cognitive tasks correctly classified 86% of the study participants. Although the patients’ motor inhibition was not clearly impaired, they showed deficient response flexibility when required both to inhibit a prepotent behavior and to execute an alternate response (the stop-change task). No group differences were attributable to comorbid ADHD.

The patients all had “narrow-phenotype” pediatric bipolar disorder, which has a clinical presentation similar to that of adult bipolar disorder

(12,

51). Like symptomatic adults with bipolar disorder, the patients in our study showed deficits in recognition of facial affect

(9). The patients also showed significant deficits in expressive pragmatic language. Although adults with bipolar disorder have difficulty interpreting cues about others’ mental states

(3,

7,

9), little research has examined expressive language pragmatics in this population. Thus, although both children and adults with bipolar disorder have social-cognitive deficits, further study is needed to clarify these deficits and their continuity across development. Use of measures that can be implemented consistently across development would facilitate such research. In addition, comparison of performance across individuals with varied psychiatric disorders will be important to determine if the observed deficits are specific to bipolar disorder.

The results regarding response flexibility and inhibition showed some consistency with reports in the literature on adult bipolar disorder. In particular, the group differences on change signal reaction time, a measure of response flexibility, resemble reports in adult bipolar disorder and pediatric bipolar disorder of deficits on tasks that require both inhibition and flexible responding

(29,

31). Also like other studies, our study showed no clear deficits on simple motor inhibition tasks

(4,

28–30). Both the literature and our data suggest that, across the developmental spectrum of bipolar disorder, deficits may be more marked on tasks that pair inhibition and execution of alternative behaviors than on tasks that involve inhibition alone. This pattern of performance could reflect many factors, ranging from differences in task complexity to differences in neural mechanisms mediating the two task types.

The present study yields evidence of some behavioral continuity across narrow-phenotype pediatric bipolar disorder and adult bipolar disorder. An important next step will be to elucidate the neural mechanisms underlying social-cognitive and response-flexibility deficits in bipolar disorder. Evidence indicates that regions including the ventral prefrontal cortex and amygdala mediate facial affect processing and that the ventral prefrontal cortex and other prefrontal areas contribute to complex inhibitory functions

(16,

18,

19,

33,

34,

52). Less is known about the neural mechanisms underlying pragmatic language, although research has implicated the frontal and temporal cortical regions

(17). Given findings of structural and functional anomalies in the prefrontal cortex and amygdala in bipolar disorder

(22–

24,

26), neuroimaging studies implementing measures of social cognition and response flexibility in pediatric bipolar disorder patients are warranted. Optimally, such studies should include clinical comparison groups to evaluate the specificity of observed anomalies.

Our inclusion of euthymic and symptomatic pediatric bipolar disorder patients allowed us to examine performance in the context of both normal and clinically significant mood states. Both euthymic and symptomatic patients performed more poorly than comparison subjects on measures of expressive pragmatic language and facial expression identification. This pattern of findings raises the possibility that social-cognitive deficits may represent trait-based vulnerability markers and possibly endophenotypes for pediatric bipolar disorder. On a measure of response flexibility, the one other task where pediatric bipolar disorder patients exhibited deficits, only euthymic patients differed significantly from comparison subjects. This finding suggests that response-flexibility deficits may represent an additional trait vulnerability marker for pediatric bipolar disorder. However, the lack of difference between the symptomatic patients and the comparison subjects is puzzling. This negative finding, which may reflect type II error, requires further study. Replication in proband and high-risk groups, as well as longitudinal study of patients across both euthymic and symptomatic states, is warranted.

This study had several limitations. The number of subjects was relatively small, and most of the pediatric bipolar disorder patients were receiving medication. However, given that group differences were selective, it appears unlikely that they were entirely related to medication. Nonetheless, examination of social cognition and response inhibition/flexibility in unmedicated youths with bipolar disorder and in children at risk for bipolar disorder is indicated. In addition, direct comparison of youths with pediatric bipolar disorder and those with other disorders, particularly ADHD/oppositional defiant disorder and the broad phenotype of pediatric bipolar disorder

(12), would provide further evidence about the specificity of our findings. We are currently conducting studies to address these limitations.

In summary, our findings, along with those from other recent studies

(31), begin to delineate a neuropsychological and social-cognitive profile for narrow-phenotype pediatric bipolar disorder. These results offer evidence of continuity between pediatric bipolar disorder and adult bipolar disorder, highlighting the need for further study using comparable measures in both populations. In addition, our findings of impairment among pediatric bipolar disorder patients on tasks involving pragmatic language, facial affect recognition, and response flexibility lay the groundwork for neurocognitive research aimed at elucidating neural mediators of these deficits.