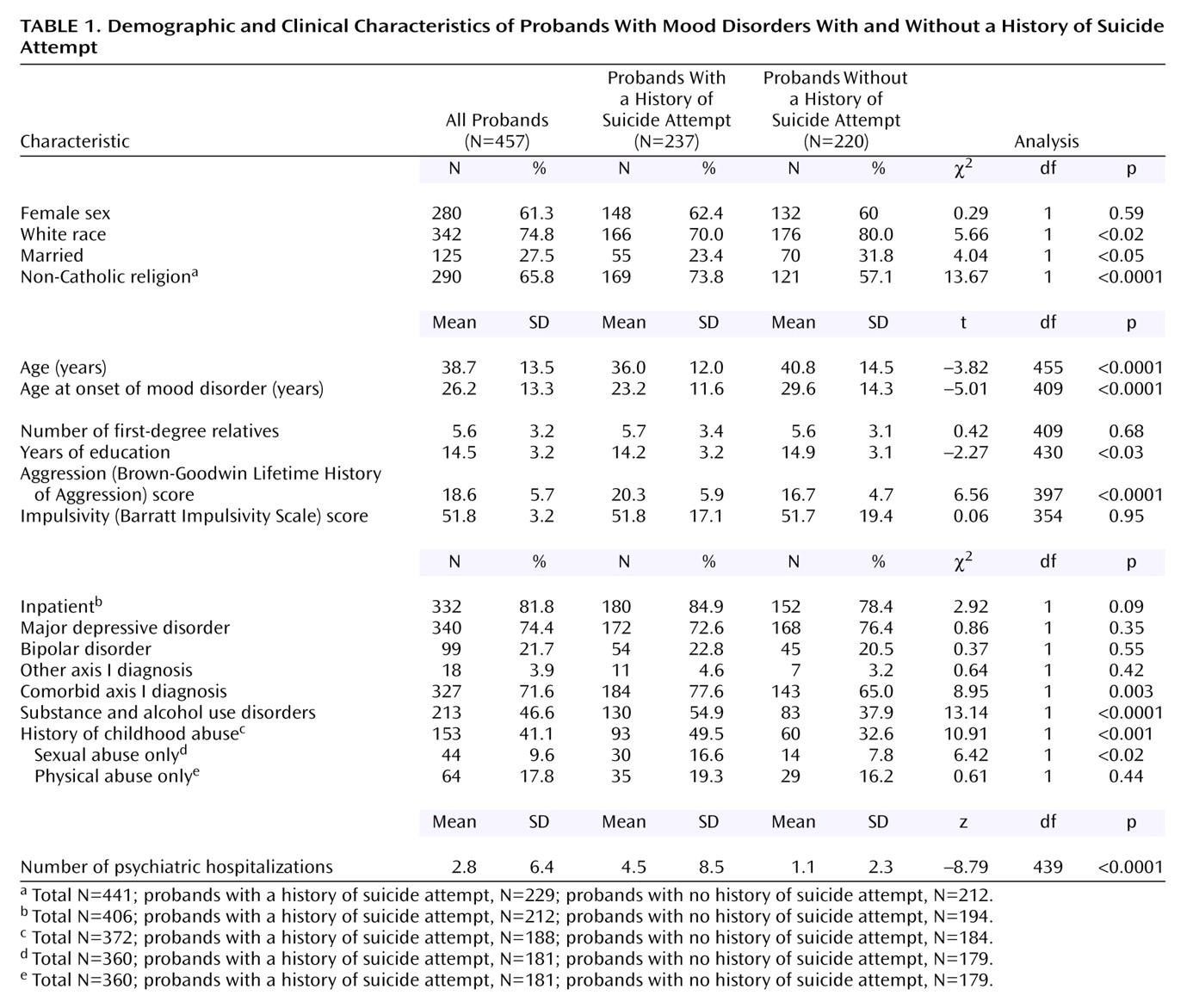

Characteristics of Proband Suicide Attempters and Nonattempters

Table 1 presents a comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics of proband suicide attempters and nonattempters. Compared to nonattempter probands, attempter probands were younger; were less likely to be Catholic, white, or married; and had slightly fewer years of education. Almost three-quarters of the probands had a lifetime diagnosis of major depressive disorder (N=340, 74.4%). The spectrum of mood disorders was comparable in proband attempters and nonattempters. Seventy-one percent (71.6%, N=327) of all probands had an additional comorbid axis I diagnosis (46.6% [N=213], alcohol and substance use disorders; 33.1% [N=72], dysthymia; 30.4% [N=66], panic disorder; 16.5% [N=36], PTSD; and 11.9% [N=26], bulimia). Probands with bipolar disorder were less likely to have comorbid dysthymia and more likely to have comorbid panic disorder, compared with probands with major depressive disorder (data not shown). Probands who attempted suicide were more likely than nonattempter probands to have a comorbid axis I diagnosis and a substance or alcohol use disorder.

Attempter probands were on average 6 years younger than nonattempter probands at the time of mood disorder onset and reported four times as many psychiatric hospitalizations. Probands who attempted suicide were more aggressive, but not more impulsive, and more likely to report a history of childhood sexual abuse, and childhood abuse in general, than probands who had not attempted suicide.

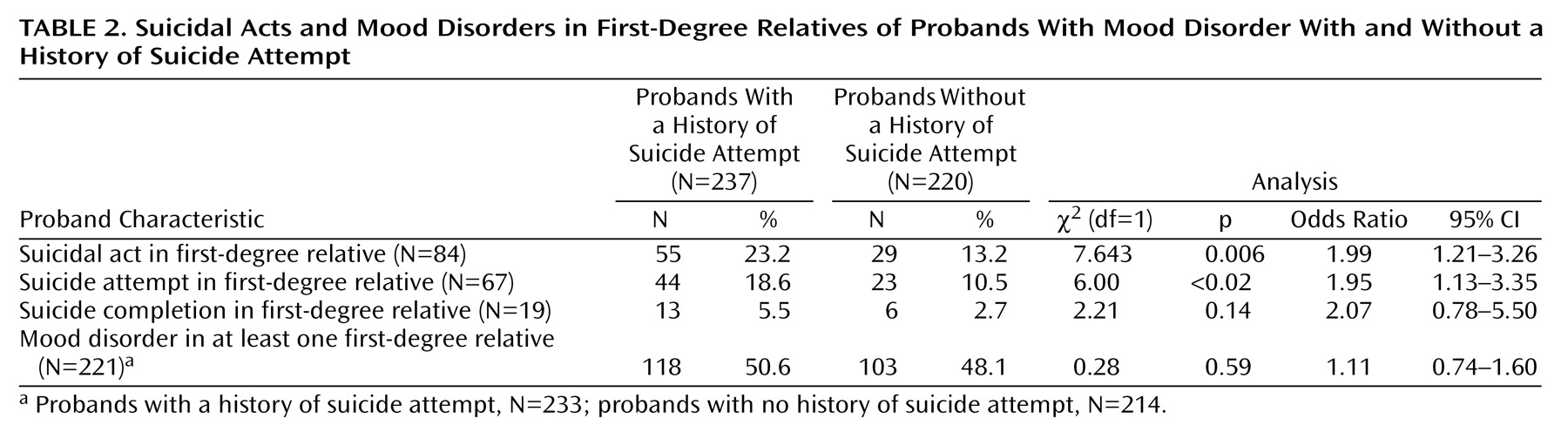

Familial Suicidal Behavior and Proband Clinical Characteristics

Table 2 gives details about suicidal behavior in first-degree relatives in relation to probands’ suicide attempt status. Probands who attempted suicide were more likely than nonattempter probands to have a first-degree relative with at least one suicidal act (attempt or completion). Significantly more attempter probands than nonattempter probands had at least one first-degree relative who had made a suicide attempt. However, there was no significant association between suicide completions in first-degree relatives and suicide attempts in probands. The small number of first-degree relatives who died by suicide limited statistical power, but, as with suicide attempts and suicidal acts in first-degree relatives, there was an almost twofold higher rate of completed suicide in first-degree relatives of proband suicide attempters, compared to nonattempters (5.5% [N=13] versus 2.7% [N=6]). There was no difference in the rate of suicidal acts in first-degree relatives between proband suicide attempters with low-lethality attempts and those with high-lethality attempts (22% [N=27] versus 15% [N=16]) (χ

2=1.40, df=1, p=0.24). Relatives with a mood disorder had a significantly higher rate of suicidal acts, compared with relatives with no mood disorder (30.8% [N=68 of 221] versus 6.6% [N=15 of 226]) (χ

2=43.03, df=1, p<0.0001; odds ratio=6.25, 95% confidence interval=3.44–11.35).

Probands with a history of suicide attempt in first-degree relatives had a significantly younger age at onset of mood disorder than those with no history of suicide attempt in first-degree relatives (mean=22.0 years, SD=10.4, versus mean=27.0 years, SD=13.7) (t=–2.7, df=409, p=0.006). Age at mood disorder onset was not significantly earlier in probands with first-degree relatives who died by suicide than in probands with no history of completed suicide in first-degree relatives (mean=32.0 years, SD=13.0, versus mean=26.0 years, SD=13.3) (t=1.7, df=408, p=0.09). It is noteworthy that, unlike the younger age at mood disorder onset in probands with first-degree relatives who attempted suicide, older age at mood disorder onset in probands was associated with suicide completion in first-degree relatives. This difference explains the nonsignificant finding with respect to proband age at mood disorder onset in analysis in which attempts and completions in first-degree relatives were considered together as suicidal acts (t=–1.7, df=409, p=0.09).

Probands with first-degree relatives who had a history of suicidal acts had higher lifetime aggression scores (Brown-Goodwin Lifetime History of Aggression) than probands with no first-degree relatives with a history of suicidal acts (mean=20.1, SD=5.6, versus mean=18.2, SD=5.7) (t=2.5, df=397, p<0.02) and a higher rate of comorbid alcohol and substance use disorders (59.5% [N=50] versus 43.8% [N=163]) (χ2=6.79, df=1, p=0.009) but similar rates of other axis I comorbidity (21.2% [N=46] versus 15.8% [N=38]) (χ2=2.19, df=1, p=0.14). Within the proband suicide attempter group there was no difference in lifetime aggression score between those with or without a family history of suicidal acts (mean=21.0, SD=5.4, versus mean=20.1, SD=6.1) (t=0.92, df=209, p=0.36). Lifetime impulsivity, measured with the Barratt Impulsivity Scale, was significantly higher in probands with first-degree relatives with a history of suicide attempts (mean=56.6, SD=14, versus mean=50.9, SD=18) (t=2.09, df=354, p<0.04) but not in probands with first-degree relatives who died by suicide (mean=49.1, SD=21, versus mean=51.9, SD=18) (t=–0.58, df=354, p=0.56) or in probands with first-degree relatives with a history of suicidal acts (both attempted and completed suicide) (mean=55.1, SD=16, versus mean=50, SD=18) (t=1.60, df=354, p=0.11). Probands who reported a history of childhood abuse were more likely to have first-degree relatives with a history of suicidal acts (26.1% [N=40] versus 14.1% [N=31]) (χ2=8.30, df=1, p=0.004). The rates of suicidal behavior in first-degree relatives did not differ in probands with physical, compared to sexual, abuse histories (data not shown).

Familial Mood Disorder and Proband Clinical Characteristics

The rates of mood disorders in first-degree relatives of suicide attempter and nonattempter probands were high and comparable: 50.6% (N=118 of 233) and 48.1% (N=103 of 214), respectively (

Table 2). Probands with first-degree relatives with a history of mood disorder had a significantly earlier age at onset of mood disorder than those without first-degree relatives with a history of mood disorder (mean=24.3 years, SD=12.1, versus mean=28.5 years, SD=14.2) (t=3.1, df=400, p=0.002). There were no differences between probands with or without first-degree relatives with mood disorders in lifetime impulsivity score (mean=53.4, SD=18, versus mean=49.7, SD=18) (t=1.89, df=347, p=0.06), aggression score (mean=18.6, SD=5.6, versus mean=18.6, SD=5.8) (t=–0.17, df=391, p=0.86), or reported history of childhood abuse (44% [N=100] versus 36% [N=50]) (χ

2=2.05, df=1, p=0.15). Among probands with first-degree relatives with a history of mood disorder, those who reported a history of childhood abuse were more likely to report physical rather than sexual abuse (66% [N=47] versus 45% [N=32]) (χ

2=4.50, df=1, p<0.04). Unlike familial suicidal behavior, rates of comorbid substance and alcohol use disorders did not distinguish probands with and without a first-degree relative with mood disorder (data not shown).

Proband Childhood Abuse, Aggression, and Age at Onset of Mood Disorder

Forty-one percent (41%, N=153 of 372) of all probands reported a history of childhood abuse. Abused probands had higher lifetime aggression scores than those with no reported abuse history (mean=19.5, SD=5.6, versus mean=17.0, SD=5.0) (t=4.22, df=334, p<0.0001) but similar lifetime impulsivity scores (mean=53.8, SD=17, versus mean=50.4, SD=19) (t=1.59, df=313, p=0.11). Lifetime aggression scores were higher in proband suicide attempters who reported a history of childhood abuse than in proband attempters with no abuse history (mean=20.7, SD=5.7, versus mean=18.2, SD=5.3) (t=2.87, df=169, p=0.005). Proband aggression, impulsivity, and age at onset of mood disorder did not differ in probands with physical, compared to sexual, abuse histories (data not shown).

Younger age at mood disorder onset was associated with a history of childhood abuse (mean=23.8 years, SD=13, versus mean=26.8 years, SD=12) (t=–2.30, df=343, p<0.02). A modest, but significant, negative correlation was found between age at onset of mood disorder and lifetime aggression score (Pearson’s r=–0.17, N=368, p<0.02), meaning that younger age at onset of mood disorder was associated with more lifetime aggression.

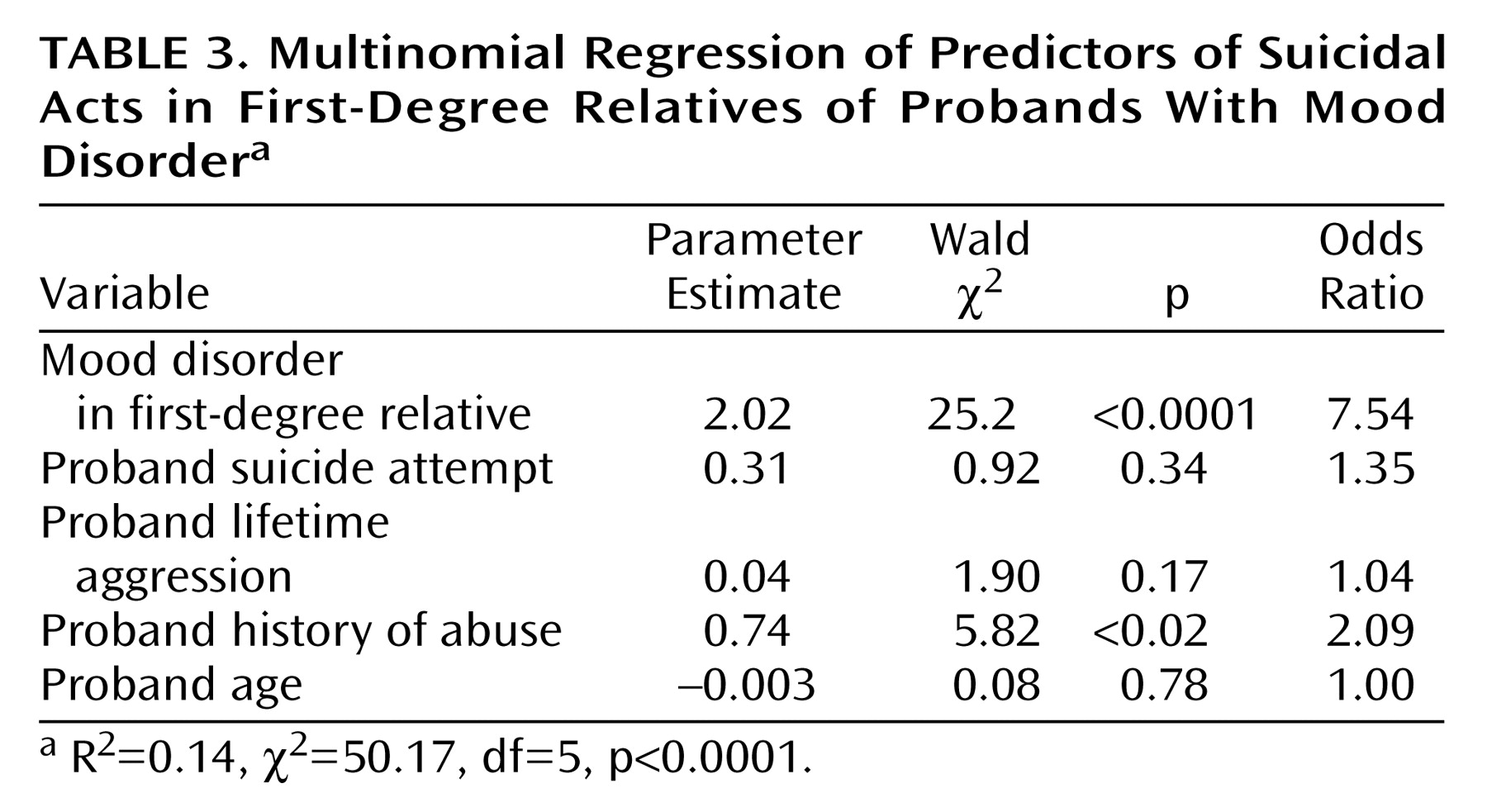

Regression Analyses

All four multivariate models were highly significant predictors of suicidal behavior in first-degree relatives of probands with mood disorders (χ

2=44.5–54.03, df=2–5, p<0.0001), and in all four models mood disorder in first-degree relatives was a significant independent predictor of suicidal behavior in first-degree relatives (p<0.0001). In the first model, proband suicide attempt was an independent predictor (β=0.75, Wald χ

2=7.86, df=1, p=0.005). In the second model, which included the aggression score, the results for proband suicide attempt (β=0.53, Wald=3.31, df=1, p=0.07) and aggression score (β=0.05, Wald=3.65, df=1, p=0.06) approached significance, suggesting a mediating effect of aggression on the effect of proband suicide attempt with respect to predicting suicidal acts in first-degree relatives. The third model differed from the first model by the addition of proband history of childhood abuse, which was predictive of suicidal acts in first-degree relatives (β=0.73, Wald=6.51, df=1, p<0.02) but had nonsignificant results for proband suicide attempt (β=0.48, Wald=2.75, df=1, p=0.10), indicating that the relationship between proband suicidal behavior and suicidal behavior in first-degree relatives may also be mediated by proband childhood abuse. In the final model, which included both aggression score and proband history of childhood abuse, proband history of childhood abuse was significant, but proband age, suicide, attempt, and aggression were not (

Table 3).