Major depressive episode is a common, chronic, and debilitating disorder. Recent estimates indicate that the lifetime prevalence of major depressive episode among adults in the United States is 16.2% and 6.6% in any given 12-month period

(1). Yet, major depressive episode is not equally distributed: African Americans report lower rates of major depressive episode than do whites, especially if sociodemographic variation is taken into consideration

(1,

2). The prevalence of major depressive episode among Hispanics is often reported to be comparable to that among whites but has been shown to vary by degree of acculturation

(3). Furthermore, the rate of depression among Asian Americans may be as low as 3.4%

(4).

To date, few studies have included sufficient numbers of American Indians to reach conclusions about the prevalence of major depressive episode in these populations. (We note that in 1977, the National Congress of American Indians and the National Tribal Chairmen’s Association issued a joint resolution that the preferred term, in the absence of specific tribal designation, was American Indian rather than Native American when referring to the indigenous population of the lower 48 states.) Two efforts, both conducted with nonrandom samples of separate tribes with semistructured clinical interviews, reported lifetime rates of depressive disorder in excess of 25%

(5,

6). The American Indian Service Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk and Protective Factors Project (AI-SUPERPFP) was designed to allow joint analyses with the baseline National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) by using DSM-III-R diagnoses generated by the University of Michigan Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI)

(7).

As we began AI-SUPERPFP, we hypothesized that the prevalence of major depressive episode among American Indians would be comparable to, if not higher than, that reported in the NCS. Preliminary analyses using the NCS algorithms for diagnosis indicated that lifetime rates of major depressive episode among American Indians were only about 30% of those reported in the NCS. This startling finding led us to carefully review the component parts of the CIDI’s operationalization of major depressive episode. We hypothesized that cultural factors would be at least partly responsible for the patterns found. Another likely factor in these differences was whether the major depressive episode symptoms co-occurred with one another. Our ethnographic reviews of the CIDI before fielding suggested that the co-occurrence questions were particularly problematic in these American Indian communities.

Results

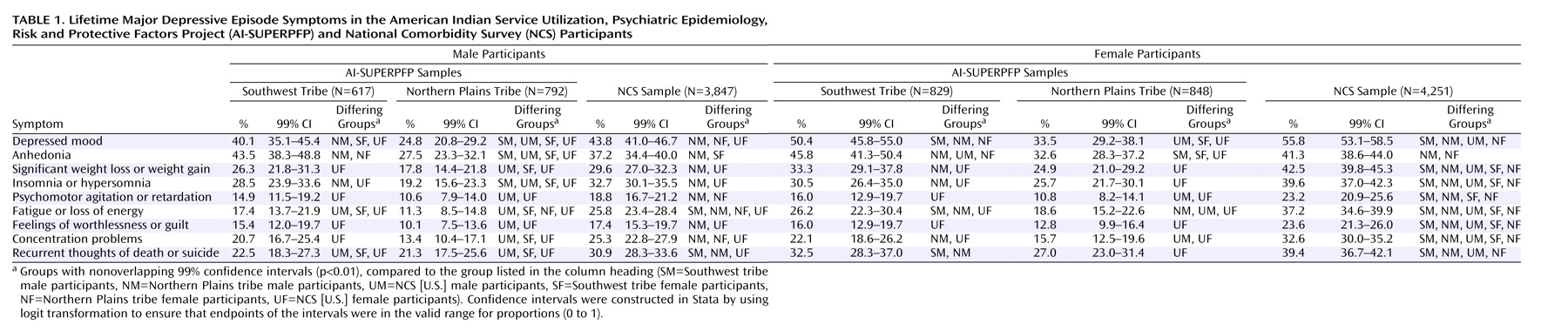

Symptom Endorsement

Table 1 provides a detailed account of the endorsements of the criterion A lifetime symptoms for major depressive episode among the Southwest, Northern Plains, and NCS samples. Both Northern Plains men and women were less likely to endorse each of the major depressive episode symptoms than were their counterparts of the same gender in the NCS. Southwest men were less likely than men in the NCS to endorse two of the nine lifetime major depressive episode symptoms, while Southwest women were less likely than women in the NCS to endorse six of the nine symptoms. It is also noteworthy that the Southwest participants were more likely to endorse depressed mood or anhedonia than were their Northern Plains counterparts.

Meeting the Diagnostic Criteria

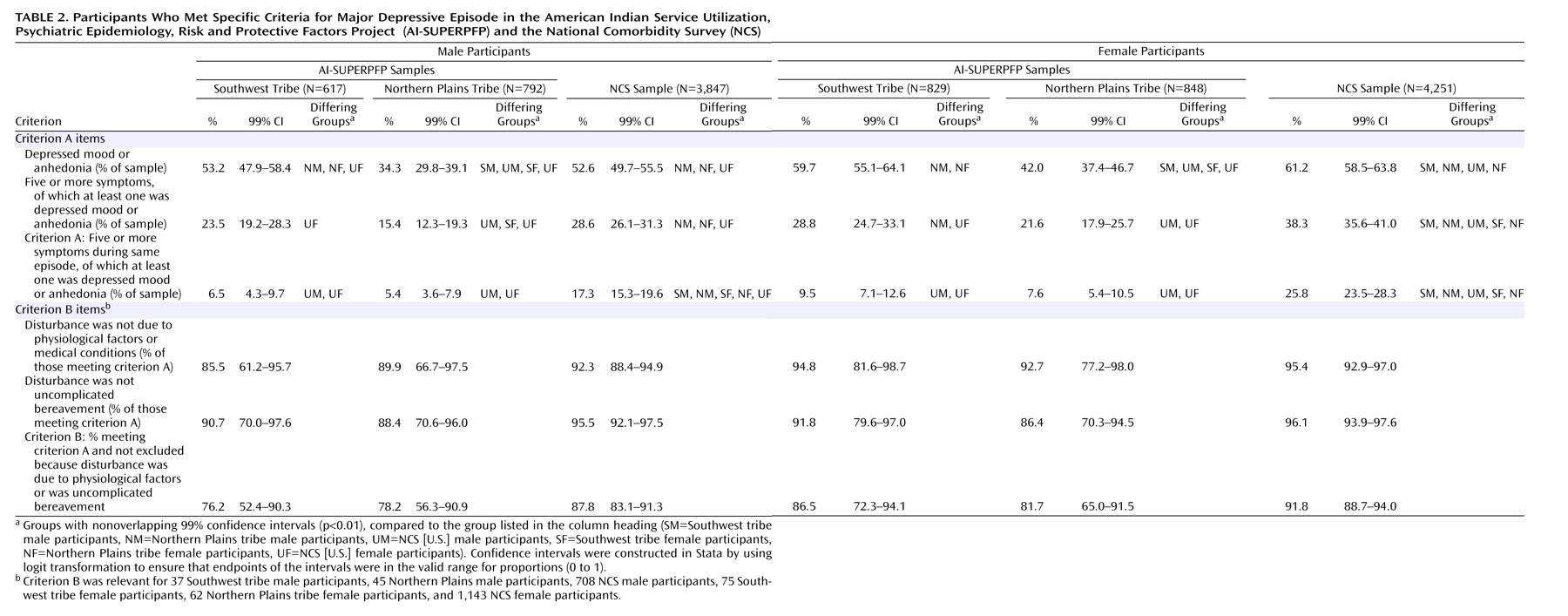

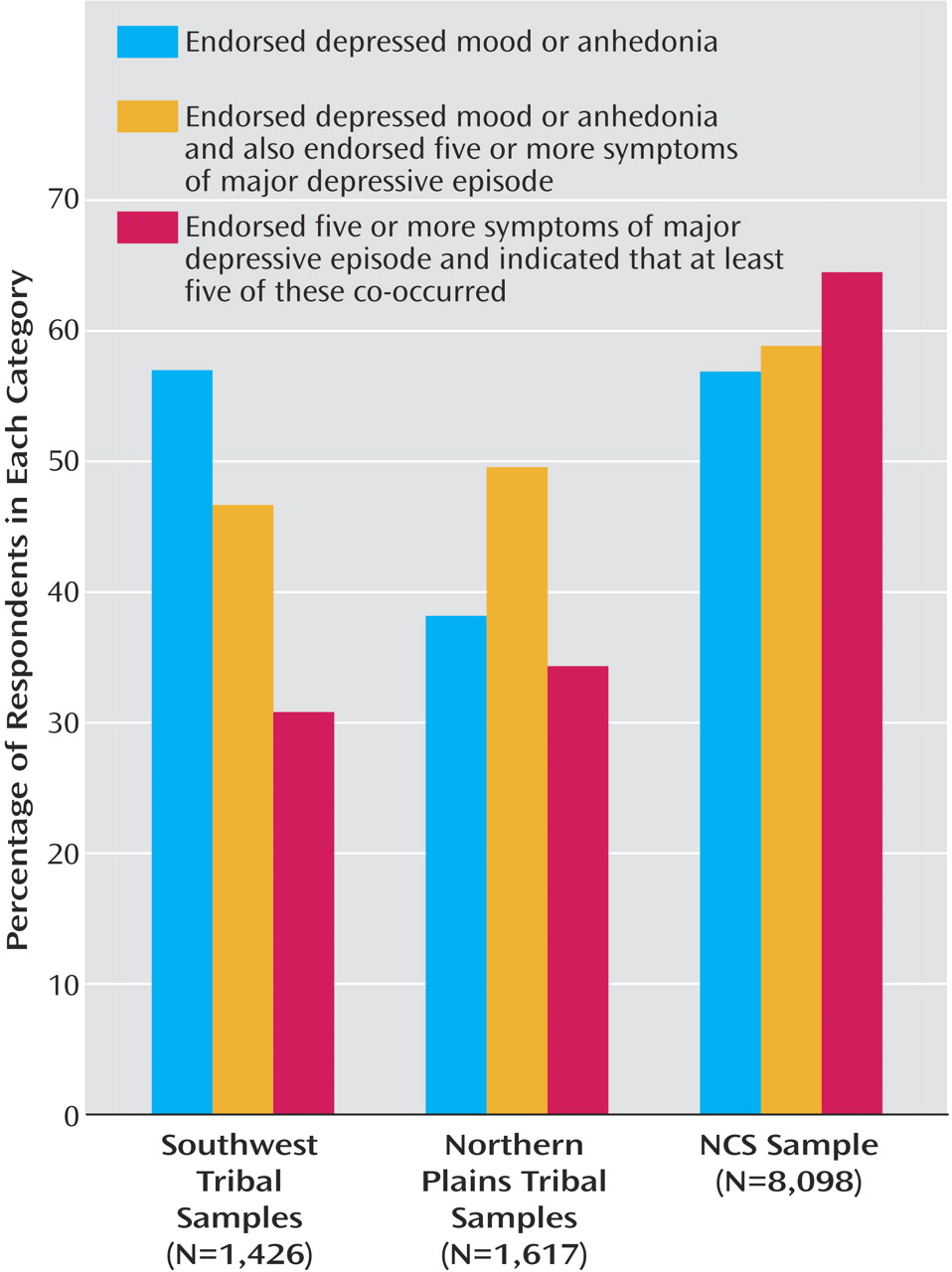

Criterion A comprises three components: at least one of the symptoms endorsed is depressed mood or anhedonia, at least five of the nine symptoms are endorsed, and five of these symptoms must co-occur within the same 2-week period. As the first row of

Table 2 shows, although more than 50% of the Southwest and NCS samples endorsed depressed mood or anhedonia, fewer Northern Plains tribal members endorsed either of these symptoms. Respondents who did not endorse at least one of these symptoms were not asked the remaining questions about symptoms of major depressive episode; the patterns for the Northern Plains participants shown in

Table 1 reflect, in part, that many in this group were not asked about the remaining symptoms.

The second row of

Table 2 presents the second component of criterion A: the percentage of respondents in each sample who endorsed at least five of the nine possible symptoms (of which at least one is depressed mood or anhedonia). Women in the NCS were most likely to report this number of symptoms; Northern Plains men, Northern Plains women, and Southwest women were less likely than their NCS counterparts to do so. As shown in the third row, the application of the third component of criterion A—the co-occurrence of five symptoms—led to further variation across samples and yielded rates for criterion A for the American Indian samples that were approximately one-third of those for the NCS samples.

The final three rows in

Table 2 show the effect of the criterion B exclusions for individuals who met criterion A. However, the diminished AI-SUPERPFP sample sizes caused by the low rate of endorsement of criterion A decreased power to identify significant differences here and rendered the effect of criterion B, including physiological factors, relatively minor.

Figure 1 graphically displays the differential effect of the components of the criterion A operationalization on major depressive episode diagnosis. For both the Southwest and NCS samples, many participants endorsed either depressed mood or anhedonia; the comparable rate for the Northern Plains was substantially lower. Approximately 50% of those endorsing depressed mood or anhedonia in the Southwest and Northern Plains also met the requirement for five or more major depressive episode symptoms, compared with almost 60% in the NCS sample. The co-occurrence requirement is where the largest discrepancies were noted. Less than one-third of the American Indians who endorsed five or more symptoms indicated that at least five co-occurred; the parallel percentage in the NCS sample was 64%.

As mentioned earlier, the focus groups that reviewed the CIDI identified the co-occurrence question as highly problematic, and the results described here bear out these qualitative findings. This convergence of ethnographic and epidemiologic findings led to consideration of an alternative algorithmic definition for major depressive episode for the AI-SUPERPFP—one that did not include the problematic formats involved in the co-occurrence question. The AI-SUPERPFP algorithm for the diagnosis simply required at least five major depressive episode symptoms—one of which was either depressed mood or anhedonia. We tested how this alternative definition fared, compared to the clinical reappraisal diagnoses. We focused on testing the following hypothesis: The NCS algorithm, which was more stringent and followed the DSM definition of major depressive episode more closely, would show superior agreement with the clinical reappraisal diagnosis (made with the SCID-NP), compared with the less stringent AI-SUPERPFP algorithm.

Validity Analyses

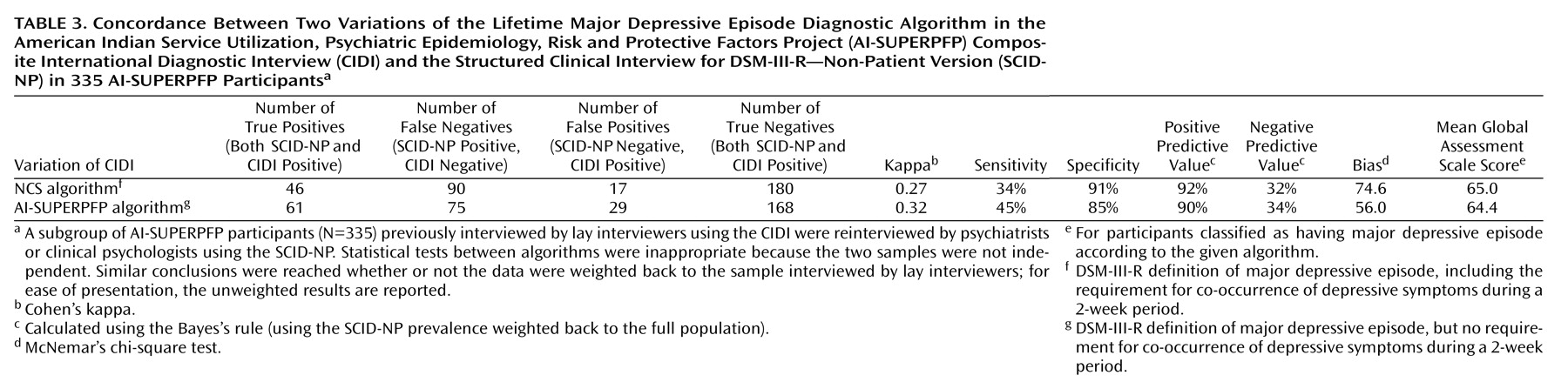

As

Table 3 shows, the kappa statistic of chance-corrected agreement with the SCID-NP diagnosis was lower, not higher, for the more stringent NCS operationalization than for the AI-SUPERPFP operationalization. Furthermore, the increase in sensitivity for the AI-SUPERPFP version was greater than was the decrease in specificity, compared to the NCS operationalization. Bias, as measured by McNemar’s test

(14), was lower with the AI-SUPERPFP version of the major depressive episode algorithm. Also, Global Assessment Scale

(15) scores were comparable across the major depressive episode algorithms; thus, participants classified as having major depressive episode under the less stringent AI-SUPERPFP algorithm were rated by the clinicians as having levels of impairment similar to those reported by participants classified as having major depressive episode with the NCS algorithm. In summary, the hypothesis that the NCS version would prove superior to the AI-SUPERPFP algorithm was not supported.

Although the results are not reported in detail, we explored several additional hypotheses. Joint analyses of data for dysthymic disorder and minor depression indicated that the American Indian participants were not more likely to qualify for these depressive disorder diagnoses than were the NCS participants. Lifetime rates of dysthymic disorder were 7.0%, 3.7%, and 6.4% for the Southwest, Northern Plains, and NCS samples, respectively; the respective lifetime rates of minor depression were 7.8%, 5.3%, and 13.0%. Furthermore, tribe, age, gender, poverty status, marital status, ethnic identity, and stigma of mental illness did not differentiate individuals who qualified for a diagnosis with the AI-SUPERPFP algorithm from those who qualified with the NCS algorithm. Thus, for the AI-SUPERPFP samples, relying on simple symptom counts for defining major depressive episode appeared preferable to requiring co-occurrence of symptoms—especially as elicited by CIDI questions.

Prevalence of Major Depressive Episode in AI-SUPERPFP

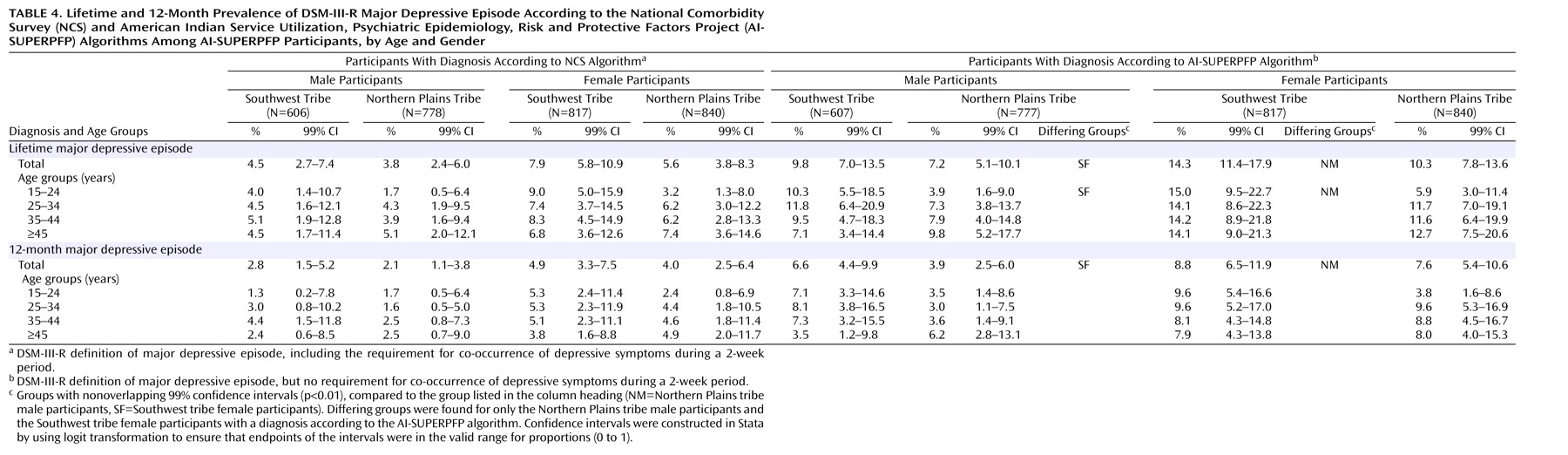

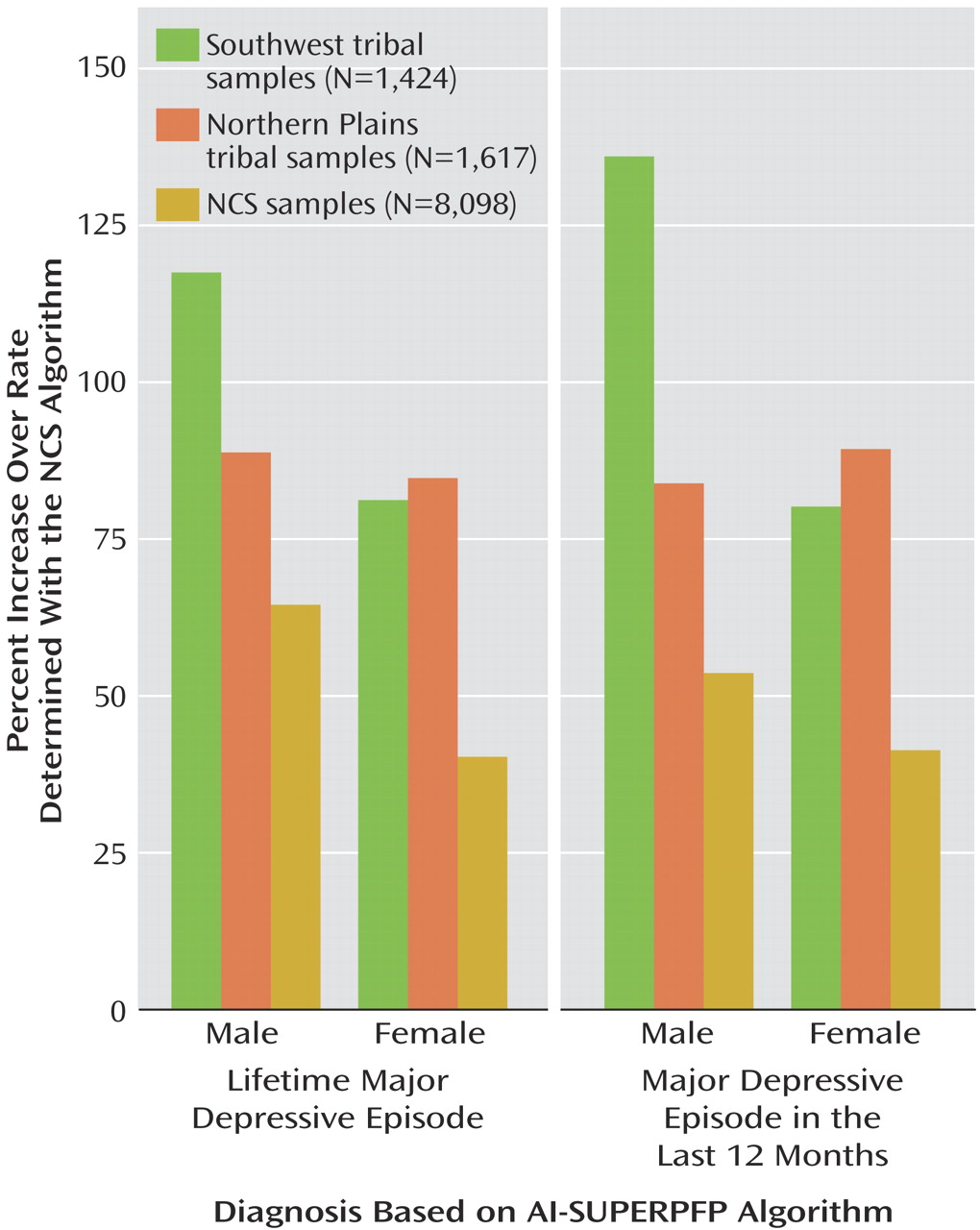

Table 4 presents the prevalence rates of major depressive episode in the AI-SUPERPFP samples calculated with both the NCS algorithm and the AI-SUPERPFP adaptation that foregoes the co-occurrence requirement. Generally, the rates using the NCS algorithm were approximately one-half those using the AI-SUPERPFP algorithm. Few tribe, gender, or age differences were found.

A question arising from these analyses is whether the NCS prevalence figures would be similarly inflated if they were based on the AI-SUPERPFP major depressive episode algorithm.

Figure 2 demonstrates that the relative increases were greater in the AI-SUPERPFP samples than in the NCS sample, further supporting the argument that the changes made in the AI-SUPERPFP major depressive episode algorithm had a differential effect across the two studies.

Discussion

The current study informs ongoing debates about cultural influences on experiences of disorder and the instruments that are increasingly used to assess such categories cross-culturally. Before embarking on AI-SUPERPFP, we predicted that the rates of major depressive episode in the American Indian populations in this study would be comparable to, if not higher than, those for the general U.S. population. At the same time, however, we were mindful of evidence of ethnic differences in major depressive episode rates

(1–

4) and of extensive ethnographic work suggesting that the social construction of depressive experiences might be different in at least some American Indian communities than in the general population

(16).

Using almost identical case-ascertainment methods and the same diagnostic algorithms that were used in the NCS, we found that rates of major depressive episode for the American Indian groups were about 30% of the national estimates. The detailed analyses presented here suggest that an interface of cultural and methodological factors is responsible for these unexpected findings. As

Figure 1 shows, members of the Northern Plains tribe were less likely to endorse the core major depressive episode symptoms of depressed mood or anhedonia. Historically, in this culture, admission of such symptoms may be relatively proscribed as signs of weakness

(17). Given the structure of the major depressive episode diagnostic module in the CIDI, however, failure to endorse these symptoms precludes diagnosis. In the Southwest tribe, depressed mood or anhedonia was endorsed at levels similar to those in the NCS sample, but the rates of endorsement of the other major depressive episode symptoms were lower, suggesting a differential social construction of major depressive episode or a disparate patterning of depressive symptoms in this culture, compared with others in the United States or in the Northern Plains tribe.

Although tribal differences may account for the dissimilar symptom endorsements, both American Indian samples struggled with the interview question about co-occurrence of symptoms. Only about one-third of American Indian participants who endorsed five or more symptoms indicated at least five co-occurring symptoms, compared to more than 60% in the NCS sample. The mean number of symptoms endorsed differed by less than 1 across samples and is thus unlikely to account fully for this difference. In the ethnographic review of the CIDI, extensive discussion was devoted to understanding why participants found these questions difficult. In particular, the necessary conceptualization of time frames was problematic—both to comprehend and to fit with individuals’ experiences. In fact, as explained earlier, because of the foreign nature of the task, we were asked to define the word “period” in the interview. During training and data collection, the co-occurrence question arguably received the greatest attention of the more than 3,000 items in the full interview. We were repeatedly advised that both interviewers and participants had difficulty understanding the required task. Indeed, our concern about administrative difficulties was so great that we completed a reinterview of a large subsample of both tribes with the major depressive episode module to assure ourselves that these questions were being administered appropriately and that rates did not change dramatically between administrations.

Memory recall, event boundaries, and perceived affinities among stimuli are key topics in cognitive psychology. The difficulty of AI-SUPERPFP participants in employing time as a frame of reference for judgments about the co-occurrence of depressive symptoms may illustrate differences in perceiving, remembering, and communicating structure in events

(18), a process likely rooted in cultural traditions of learning

(19). In particular, we were told that what we were labeling depression was not necessarily experienced as episodic; thus, questions that asked specifically whether each depressive symptom was present at a given time were very difficult to address. Responding to such questions is clearly a complex cognitive task that may be made more difficult because the diagnostic interview is structured with the assumption that depressive episodes and temporality are similarly constructed cross-culturally. We note that the more recent NCS replication

(1) simplified the co-occurrence question and did not ask for a symptom-by-symptom accounting. At the same time, other aspects of the new NCS interview are clearly more complicated than previous versions; for instance, detailed judgments about the duration of some symptoms are required. We argue that at a minimum, the complex wording of diagnostic interview questions may present significant difficulties cross-culturally. More critically, however, these findings suggest that the cross-cultural validity of the measurement of major depressive episode merits further investigation.

These data and analyses have limitations, many of which have been discussed at length elsewhere

(9). Briefly, the AI-SUPERPFP samples, while well defined and well justified, were limited. The restricted age range mirrored that of NCS. The limited tribal representation and the focus on only those tribal members currently resident on or near their home reservations were decisions driven by the need to balance cultural variability with feasibility

(9). Joint analyses of data sets such as AI-SUPERPFP and NCS are limited methodologically. The data collection periods necessarily varied, as did the methods—at least to a certain extent. The NCS data were collected in 1990–1992; the AI-SUPERPFP data, between 1997 and 1999. Furthermore, the response rates for AI-SUPERPFP were somewhat lower than those of NCS: 75% combined across tribes, compared to 83% for NCS

(10). However, the AI-SUPERPFP rates are similar to those of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study—between 68% and 79% by site

(20)—and the 73% response rate reported for the recent NCS replication

(1).

Another limitation is the low concordance rates between the AI-SUPERPFP CIDI and the SCID-NP, although it should be noted that the kappa values in our study approximate those in other studies that have used this generation of instruments

(21). More important here, however, was that our results did not support our hypothesis that the clinicians’ diagnoses, which were less dependent on the use of specific question wording, would demonstrate greater concordance with the more stringent NCS operationalization.

In summary, the pattern of these findings is reasonable given existing knowledge about the cultural factors that influenced this study. We note that even with the more liberal AI-SUPERPFP operationalization, the rates of major depressive episode for the American Indian samples remained significantly lower than those reported for the NCS sample

(22). Our results underscore the importance of integrating qualitative and quantitative methods for understanding depressive and other disorders within the purview of the DSM. As new versions of the CIDI

(1) are modified to more closely reflect the clinical diagnostic process, the instrument is likely to become increasingly complicated and to rely more heavily on intricate time frames and language. Such changes are likely to increase cultural variability in endorsement patterns and in the subsequent estimates of mental illness.