Premenstrual dysphoria and perimenopausal depression are mood disorders that are characterized by the appearance of symptoms during distinct periods of reproductive hormone change. Both direct and indirect data suggest that changes in gonadal steroids trigger these disorders (as well as postpartum depression); therefore, they may represent different manifestations of the same underlying diathesis. Studies have demonstrated that women with prospectively confirmed premenstrual dysphoria whose symptoms remit after induced hypogonadism (ovariectomy or administration of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist) experience a recurrence of premenstrual dysphoria symptoms after the exogenous administration of ovarian steroids

(1,

2). Evidence of similar underlying processes in perimenopausal depression is indirect and includes the efficacy of estradiol therapy in the acute treatment of perimenopausal depression

(3,

4). Additionally, the results of longitudinal studies have suggested that perimenopausal changes in reproductive function are associated with an increased risk of depression compared to both the premenopausal and postmenopausal years

(5–

9). Speaking against the existence of a common diathesis in these conditions is the observation that estradiol increases premenstrual dysphoria

(1) but decreases perimenopausal depression

(3,

4). Nonetheless, three types of evidence have been proposed to suggest that premenstrual dysphoria and perimenopausal depression (as well as postpartum depression) are part of a continuum of disorders sharing a similar pathophysiology

(10,

11). First, several clinic-based studies have observed that women reporting mood disturbances during perimenopause also report severe premenstrual mood symptoms

(12–

15). Second, community-based studies have identified an association between self-reports of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and a risk for women to develop clinically significant mood symptoms during perimenopause

(16,

17). Finally, some

(18–

20) but not all

(21) studies have suggested that the efficacy of estradiol therapy in PMS is similar to that observed in the treatment of perimenopausal depression.

These observations have led some investigators to conclude that premenstrual dysphoria is both an antecedent as well as a frequent accompaniment of perimenopausal depression. The co-occurrence of these conditions might suggest the presence of a risk for mood destabilization during periods of reproductive endocrine change, with the specificity of the trigger (e.g., estradiol withdrawal, increasing estradiol levels, oral contraceptives) determined by other factors. Studies that reported the association between premenstrual dysphoria and perimenopausal depression are limited by several methodological problems, including the failure to prospectively confirm the diagnosis of premenstrual dysphoria

(12,

15), thus likely resulting in an overstatement of the number of women who would have met standardized criteria for premenstrual dysphoria. Similarly, studies lacking both hormonal evidence of perimenopausal ovarian function

(12,

16) as well as a standardized diagnosis of the syndrome of depression

(14,

16,

17) may have overestimated the co-occurrence of these conditions. Studies of the comorbidity of affective disorders in premenstrual dysphoria have documented that up to 60% of women with premenstrual dysphoria will also experience episodes of major depression

(22–

26). Thus, in many women with premenstrual dysphoria during midlife, depression could occur coincidentally with midlife and not be related to perimenopause. Consequently, unless perimenopausal status is confirmed, women with premenstrual dysphoria may have an episode of depression occurring independently of a change in reproductive endocrine function.

In this study, we investigated the nature of the relationship between premenstrual dysphoria and perimenopause-related depression. In a group of women with well-characterized perimenopause-related mood problems, we identified the number of women with self-reports of premenstrual dysphoria, those with evidence of prospectively confirmed premenstrual mood cyclicity, and, finally, those with confirmed significant premenstrual dysphoria.

Method

Subject Selection

The subjects were women attending a menopause clinic who were between the ages of 40 and 55 and had depression in association with a history of menstrual-cycle irregularity of at least 6 months’ duration but not greater than 1 year of amenorrhea. The 315 women who came to the menopause clinic with adverse mood symptoms were screened for inclusion in this study. Of these subjects, we selected 70 women with depression who also met the following selection criteria: 1) a single measurement of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level (taken on the first visit) ≥14 IU/liter, which represents approximately two standard deviations above the mean value for early follicular-phase FSH levels in women between the ages of 25 and 35, consistent with the criteria for perimenopause suggested by the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop

(27); 2) a 21-item Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score of ≥10

(28,

29); and 3) daily symptom ratings completed for at least 1 month during which at least one menses (at least 3 days of menstrual bleeding) occurred.

The subjects were self-referred in response to local advertisements or were referred by their physicians. All of the women were medication free during the study period. Written informed consent to measure plasma hormone levels and monitor mood symptoms was obtained from each woman before her participation.

The comparison subjects were 35 nondepressed perimenopausal women who were recruited separately through advertisements in the hospital newsletter. The nondepressed, healthy, medication-free comparison subjects participated in a similar screening program and met the same clinical (i.e., age, menstrual cycle history) and laboratory (i.e., FSH level) requirements as the depressed perimenopausal women, with the exception of the absence of complaints of mood symptoms and the elevated BDI score criterion, confirmed by the administration of the structured diagnostic interview and standardized mood rating scales (previously described). The comparison subjects were excluded if they had any current or past axis I psychiatric condition. They received remuneration for their participation in the study, as determined by the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Office of Normal Volunteers. The protocol was approved by the National Institute of Mental Health Intramural Research Review Subpanel.

Symptom Ratings

A semistructured questionnaire was administered by one of the clinical research staff at the National Institute of Mental Health midlife clinic that inquired about the presence of premenstrual mood symptoms. All women were asked if they experienced premenstrual symptoms, followed by specific questions about the presence of premenstrual depression, irritability, anxiety, and food cravings. The Daily Rating Form

(30) was completed, which rated the severity of several mood and behavioral symptoms, including the following: mood swings, depression, anxiety, irritability, social isolation, loneliness, lethargy, impaired concentration, increased appetite, decreased sexual interest, disturbed sleep, and functional impairment. Additionally, the Daily Rating Form was modified to include the symptoms of daytime and nighttime hot flushes. The presence of hot flushes was operationally defined by a mean score >2 on the Daily Rating Form (2=minimal) during the 8-week baseline. The subjects were instructed to use the severity scale as a composite of their hot flush frequency and severity.

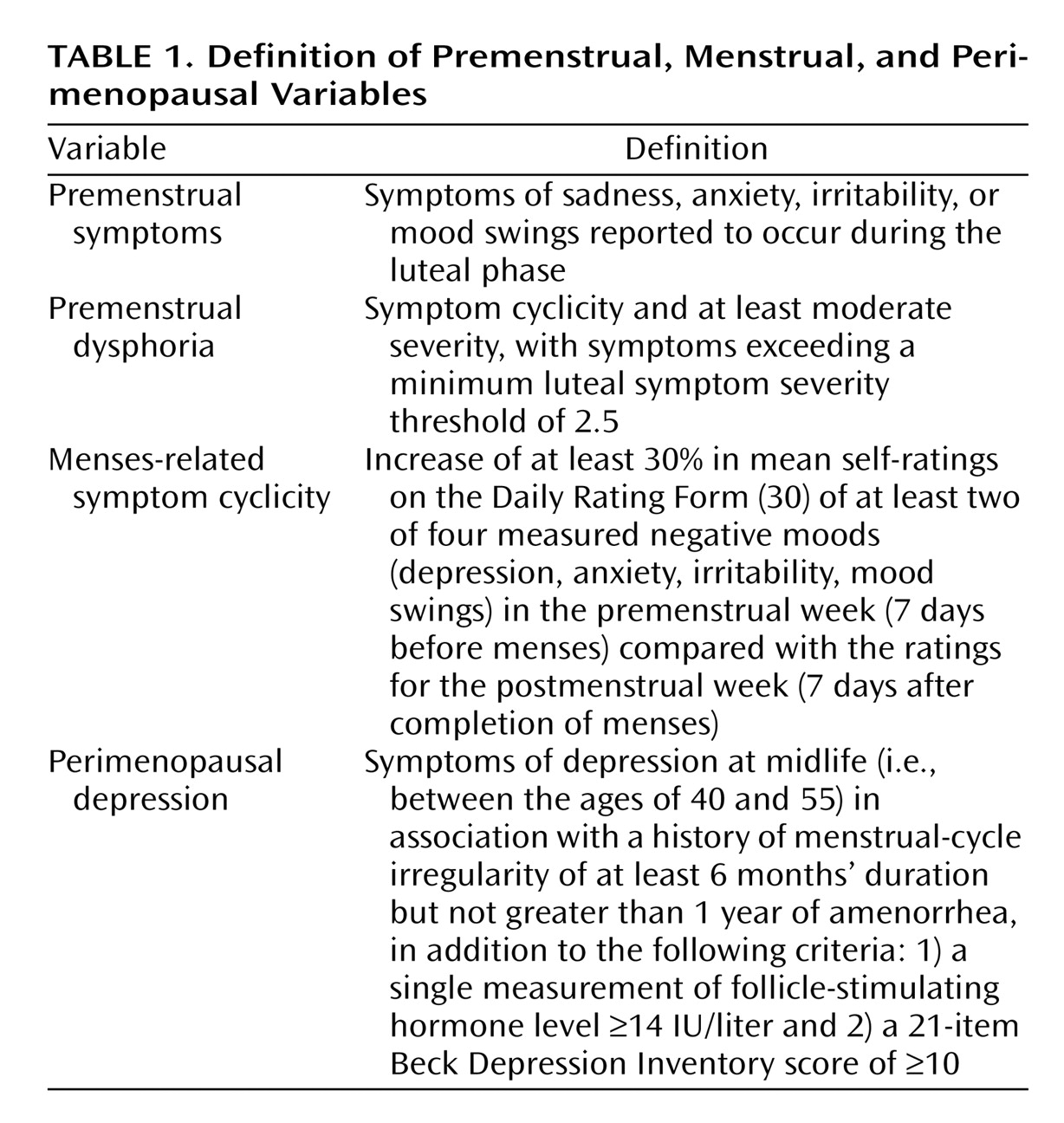

First, we identified the number of women reporting premenstrual dysphoria symptoms (

Table 1). Second, the Daily Rating Form was employed to assess symptom cyclicity. Menses-related symptom cyclicity was operationally defined as an increase of at least 30% (relative to the range of the scale [i.e., 5 points]) in mean self-ratings on at least two of four measured negative moods (depression, anxiety, irritability, mood swings) in the premenstrual week (7 days before menses) compared to the ratings for the postmenstrual week (7 days after completion of menses). The rating interval was limited to one menstrual cycle because most of these perimenopausal women were in late perimenopause and, therefore, had periods of amenorrhea lasting 2–3 months. On the Daily Rating Form, a 30% change in average ratings amounts to a difference of 1.5 units between the averages of the 7 days before menses and the 7 days after the end of menses. Third, the ratings from the women who met criteria for symptom cyclicity were further examined to identify the women who also met a minimum luteal symptom severity threshold of 2.5 (as a proxy for symptom severity and impairment criteria employed in making the diagnosis of severe PMS/premenstrual dysphoric disorder

[31]). The presence of menses-related symptom cyclicity and symptom cyclicity meeting the threshold luteal severity score were evaluated in both women with and women without self-reported premenstrual symptoms.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square analyses (or Fisher’s exact tests, when appropriate) were employed to compare the number of women in each group (depressed versus comparison subjects) who met the following criteria: 1) self-report of premenstrual symptoms, 2) menses-related symptom cyclicity of ≥1.5 unit difference in premenstrual to postmenstrual symptoms, and 3) severe premenstrual dysphoria, i.e., criterion 2 plus a luteal severity score of 2.5.

Results

Seventy perimenopausal women with depressive symptoms and 35 comparison subjects were studied. There was no significant difference in age between the women with perimenopausal depression (mean=47.1 years, SD=3.1) and the comparison subjects (mean=48.1 years, SD=3.6) (t=1.4, df=103, n.s.). BDI scores were significantly higher (more symptomatic) in the depressed women than in the comparison subjects (mean=19.5, SD=10.3, versus mean=4.6, SD=2.4, respectively) (t=7.0, df=103, p<0.001).

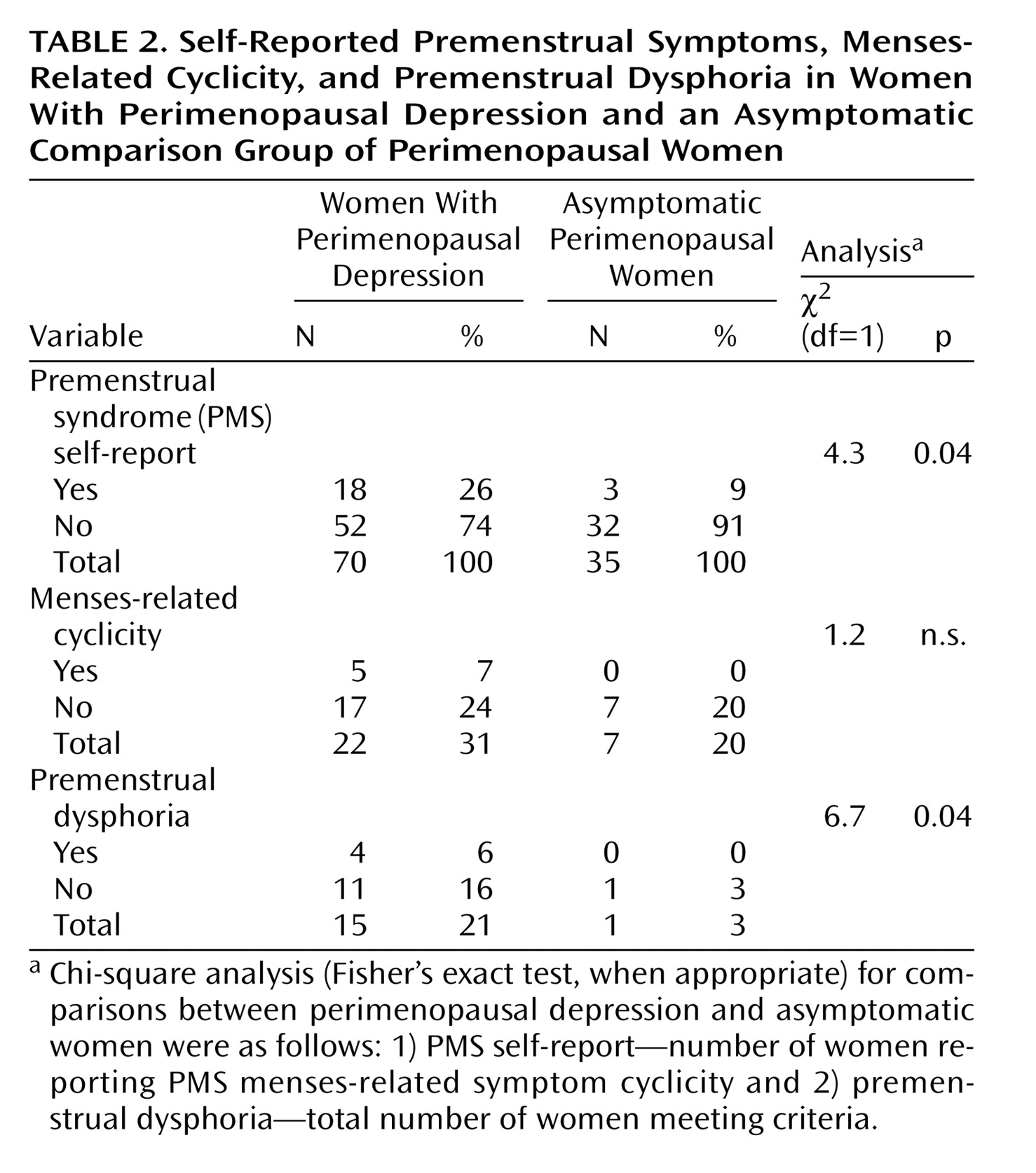

Of the 70 depressed perimenopausal women, 18 (26%) reported that they had premenstrual symptoms. The frequency with which these women and the 52 (74%) who reported no premenstrual symptoms met criteria for either the presence of significant menses-related symptom cyclicity or premenstrual dysphoria is reported in

Table 2. A total of 22 women (31%) met criteria for significant menses-related symptom cyclicity, and 15 (21%) met criteria for premenstrual dysphoria.

In the 35 perimenopausal women who were asymptomatic comparison subjects, three women (9%) reported premenstrual symptoms, but none of these met the symptom-cyclicity criteria; therefore, none also met criteria for premenstrual dysphoria. However, of the 32 asymptomatic comparison subjects who said that they did not have premenstrual symptoms, seven women met criteria for significant symptom cyclicity (seven of 35, 20%), and one of these women (3%) met the luteal phase severity threshold of ≥2.5 for premenstrual dysphoria.

The women with perimenopausal depression were significantly more likely to meet criteria for premenstrual dysphoria than the asymptomatic comparison subjects (21% versus 3%, respectively) (χ2=6.7, df=1, p=0.04). Among depressed perimenopausal women, the percentage meeting the symptom cyclicity criterion was nonsignificantly higher than in the asymptomatic comparison group (31% versus 20%) (χ2=1.2, df=1, n.s.).

Virtually no difference was seen in the percentage of women with confirmed premenstrual dysphoria among the depressed perimenopausal women who did (four of 18, 22%) and the women who did not (11 of 52, 21%) report having premenstrual symptoms. Elimination of the luteal phase severity threshold requirement (i.e., by using only the menstrual cycle phase cyclicity criterion) again resulted in comparable percentages of subjects meeting the criterion in both those endorsing and those not endorsing the presence of premenstrual symptoms (five of 18, 28%, versus 17 of 52, 33%, respectively) (p=0.80, Fisher’s exact test).

Discussion

This study had two main findings. First, we observed a higher-than-expected percentage of both menses-related symptom cyclicity and premenstrual dysphoria in perimenopausal women with depression. However, neither menses-related symptom cyclicity nor premenstrual dysphoria was a uniform accompaniment of perimenopausal depression. Second, the rate of premenstrual dysphoria was not predicted by initial self-reports.

Significantly more women with perimenopausal depression met criteria for premenstrual dysphoria than the nondepressed perimenopausal comparison subjects (21% versus 3%, respectively). Additionally, a nonsignificant increase in the percentage of those meeting the criteria for menses-related symptom cyclicity was seen in the depressed versus the nondepressed group (31% versus 20%). Although these percentages are somewhat higher than findings in several previous epidemiological samples, the liberal diagnostic criteria that we employed likely overestimated the frequency of the occurrence of both menses-related symptom cyclicity and premenstrual dysphoria

(32–

40). It is also possible that our failure to identify differences in the prevalence of menses-related symptom cyclicity reflects a type II error, and therefore, had we employed a larger group, differences might have reached statistical significance. Nonetheless, the 20%–30% rate of menses-related symptom cyclicity is comparable to that seen in several community-based

(38) and clinic-based

(41,

42) studies. Therefore, it is possible that menses-related symptom cyclicity occurs independently of the presence of significant perimenopausal depression.

The rate of premenstrual dysphoria observed in this group of depressed perimenopausal women was not predicted by initial self-reports. Indeed, the rates of both menses-related symptom cyclicity and premenstrual dysphoria were identical in the patients with and those without self-reported premenstrual symptoms. Among the comparison subjects, the rates were higher in those who did not report premenstrual symptoms. Significant menses-related symptom cyclicity in women who otherwise report the absence of premenstrual dysphoria has been reported in previous studies of reproductive-age women

(41,

42). For example, both Gallant et al.

(41) and Abraham and Mira

(42) employed criteria similar to those in this study and observed rates of significant menses-related symptom cyclicity between 20% and 47% in women who reported the absence of premenstrual symptoms. This emphasizes the importance of evaluating menstrual cyclicity in perimenopausal women as a potential source of distress, irrespective of the presence or absence of self-reported premenstrual symptoms.

Despite the higher rate of premenstrual dysphoria, the majority of women with perimenopausal depression neither met criteria for premenstrual dysphoria nor had significant symptom cyclicity. In fact, the observed rates of both premenstrual dysphoria and menses-related symptom cyclicity are overestimates of their prevalence in women with perimenopausal depression because we specifically excluded a large proportion of our original group of perimenopausal women who were amenorrheic during the screening phase of the study. Moreover, we required only 1 month of ratings to confirm the diagnosis of premenstrual dysphoria instead of the more standard requirement of at least 2 months. Thus, although we identified a group of women with both conditions, the majority of women with perimenopausal depression do not have premenstrual dysphoria. Premenstrual dysphoria, then, is not a uniform accompaniment or antecedent of perimenopausal depression. Moreover, our data would suggest that these disorders are independent and do not share the same pathophysiology despite claims to the contrary (e.g., based on treatment response to estradiol therapy)

(10,

11).

There are several possible explanations for our observation of the co-occurrence of perimenopausal depression and premenstrual mood symptoms in a subgroup of women. Perimenopause could be a course modifier for the symptoms of premenstrual dysphoria. As perimenopause progresses, there is a gradual shortening of the follicular phase

(43–

46). Thus, perimenopausal depression in women previously reporting a history of PMS could represent the elimination of follicular phase-related symptom remissions and the development of a more persistent pattern of dysphoria. Conversely, the severity of perimenopausal depression could be modulated by menses-related events causing symptoms to abate during the follicular phase or worsen during the luteal phase (in the absence of antecedent premenstrual dysphoria). Thus, in some women with perimenopausal depression, the menstrual cycle may modulate the appearance of symptoms, with exacerbations during the premenstrual phase of the cycle similar to those described for chronic depression

(47). It is also possible that for some women, premenstrual dysphoria begins in perimenopause. Thus, either age or endocrine events related to perimenopause may induce the onset of premenstrual dysphoria in some women who otherwise have not experienced the condition throughout the majority of their reproductive lives. The prevalence of comorbid premenstrual dysphoria in depressive disorders has not been systematically examined. However, by using premenstrual dysphoria criteria similar to those employed in this study, 46% of women with seasonal (winter) depression met criteria for premenstrual dysphoria during the summer when their depression was in remission

(48). Thus, higher-than-expected rates of premenstrual dysphoria in women with perimenopausal depression also could reflect an increased comorbidity for premenstrual dysphoria in depressive illness that is not specific to perimenopause.