Remission, the virtual absence of symptoms, is the aim of depression treatment because it is associated with better function and a better prognosis than is response without remission. Response is typically defined as a clinically meaningful reduction in symptoms (e.g., a reduction of at least 50% in baseline symptom levels). However, response that falls short of remission is suboptimal because it is associated with continued disabling symptoms, negative effects on other axis I and axis III disorders, higher rates of relapse and recurrence, poorer work productivity, more impaired psychosocial functioning, higher levels of health care use, and potentially higher risk for suicide. Remission, on the other hand, is associated with return of normal psychosocial function, higher rates of sustained remission, lower rates of relapse, lower risk of suicide and alcohol/drug abuse, and lack of disabling symptoms

(1–

3).

Few efficacy studies, even in research settings, have employed remission as an outcome

(4–

7). Remission rates from research-based, 8-week, randomized, placebo-controlled efficacy trials with depressed, symptomatic volunteers range from 25% to 40%

(4), and 12-week efficacy trials with subjects suffering from chronic depression reveal even more modest remission rates of 22%–30%

(8,

9).

Results from these efficacy trials lack ecological validity and generalizability to clinical practice

(10,

11). Typically, they enroll symptomatic volunteers (often recruited through advertising) with uncomplicated (minimal comorbid general medical or psychiatric conditions), nonchronic, non-substance-abusing, nonsuicidal depression and treat in research clinics as opposed to enrolling patients already seeking health care in typical clinical treatment settings. Unfortunately, no large-scale antidepressant medication trials have evaluated safety, efficacy, and tolerability in “real world” primary or psychiatric care settings with remission as the predefined primary endpoint.

Evidence from practice settings

(12) also demonstrates that antidepressant medication treatment is often inadequate in dose and/or duration and that there are unacceptably high dropout rates—all of which likely contribute to lower remission rates. In the available effectiveness trials conducted in real clinical practice settings, even the addition of depression care specialists leads to modest remission rates (15% to 35%)

(10,

13,

14).

The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study was designed to assess effectiveness of treatments in generalizable samples and ensure the delivery of adequate treatments. The study aimed to define the symptomatic outcomes for outpatients with nonpsychotic major depressive disorder treated initially with citalopram, a prototype of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). The primary outcome was remission. Adequate doses of citalopram had to be given for a sufficient time period to ensure that an adequate treatment trial was conducted to assess efficacy in representative practice settings and to ensure that those patients who progressed to the next treatment step in STAR*D were truly treatment resistant. To that end, a systematic but easily implemented approach to treatment, measurement-based care, was developed. Measurement-based care includes the routine measurement of symptoms and side effects at each treatment visit and the use of a treatment manual describing when and how to modify medication doses based on these measures. The manual allows for flexible dosing and was designed to maximize adequate dosing and duration of treatment.

Finally, since most depressed patients do not achieve remission with any initial treatment, baseline features (moderators) that identify who will achieve remission

(15,

16) are clinically important. With a rare exception

(17), no adequately powered previous studies have searched for baseline features predicting which patients will achieve remission as opposed to those who will respond to treatment. Response moderator studies with small samples have yielded inconsistent correlates of response

(18), except for pretreatment depressive symptom severity, which has been associated consistently with lower response rates

(19–

35). Therefore, STAR*D also aimed to evaluate moderators of symptom remission.

This study defined remission as the a priori primary endpoint and divided baseline moderators into three domains: 1) demographic features (e.g., age, race, ethnicity, and gender), 2) social features (e.g., education, employment status, income, insurance, and marital status), and 3) clinical features (e.g., age at onset of major depressive disorder, length of the current major depressive episode, number of major depressive episodes, length of illness, course of illness [single or recurrent], major depressive disorder subtype [anxious, melancholic, and atypical features], family history of depression, concurrent general medical and axis I psychiatric disorders, symptom severity, and functional status at baseline).

This report addresses the following questions about treatment with citalopram, a representative of the SSRI class of medications:

1.

What are the remission and response rates in representative outpatients with nonpsychotic major depressive disorder in primary and psychiatric care settings?

2.

Which citalopram doses, treatment durations, and adverse events characterize patients who do or do not achieve remission?

3.

What pretreatment features in demographic, social, and clinical domains are associated with remission?

Method

Study Overview and Organization

The rationale, methods, and design of the STAR*D study have been detailed elsewhere

(7,

36). Investigators at each of 14 regional centers across the United States oversaw protocol implementation at two to four clinical sites providing primary (N=18) or psychiatric (N=23) care to patients in both the public and private sectors. Clinical research coordinators at each clinical site assisted participants and clinicians in protocol implementation and collection of clinical measures. A central pool of research outcome assessors conducted telephone interviews to obtain primary outcomes.

Participants

All risks, benefits, and adverse events associated with STAR*D participation were explained to subjects, who provided written informed consent before entering the study. The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas and the institutional review boards at each clinical site and regional center and the Data Coordinating Center and the Data Safety and Monitoring Board of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) approved and monitored the protocol.

To maximize generalizability of findings, only patients seeking medical care in routine medical or psychiatric outpatient treatment (as opposed to those recruited through advertisements) were eligible for the study. Minimal exclusion criteria and broad inclusion criteria that allowed a majority of axis I and axis II disorders were used. Outpatients who were 18–75 years of age and had a nonpsychotic major depressive disorder determined by a baseline 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D)

(37,

38) score ≥14 were eligible if their clinicians determined that outpatient treatment with an antidepressant medication was both safe and indicated. The initial HAM-D at study entry was administered and scored by the clinical research coordinators. Patients who were pregnant or breast-feeding and those with a primary diagnosis of bipolar, psychotic, obsessive-compulsive, or eating disorders were excluded from the study, as were those with general medical conditions contraindicating the use of protocol medications in the first two treatment steps, substance dependence (only if it required inpatient detoxification), or a clear history of nonresponse or intolerance (in the current major depressive episode) to any protocol antidepressant in the first two treatment steps

(7).

Diagnostic and Outcome Measures

The diagnosis of nonpsychotic major depressive disorder, established by treating clinicians, was confirmed by a checklist based on DSM-IV criteria. Previous personal and family histories as well as clinical and demographic information were based on participant self-report. The Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire

(39–

41) was completed at baseline to estimate the presence of 11 potential concurrent axis I (psychiatric) disorders. Responses to items on the baseline 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology or HAM-D

(37,

38) obtained by research outcome assessors were used to estimate the presence of atypical

(42), anxious

(43), and melancholic

(44) symptom features.

Clinical research coordinators administered an initial HAM-D and the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), QIDS Clinician Rating (QIDS-C), and QIDS Self-Report (QIDS-SR)

(45–

47) to assess depressive symptom severity. The clinical research coordinator also completed the 14-item Cumulative Illness Rating Scale

(48,

49) to gauge the severity/morbidity of general medical conditions relevant to different organ systems. Each of the 14 illness categories was scored 0 (no problem) to 4 (extremely severe/immediate treatment required/end organ failure/severe impairment in function). The Cumulative Illness Rating Scale was scored as number of general medical condition categories endorsed (0–13, excluding the psychiatric illness category), severity index (0 to 4) (the average severity of the categories endorsed), and total severity (number of categories times severity).

The primary research outcome was measured by HAM-D score collected by research outcome assessors with telephone-based structured interviews in English or Spanish. Research outcome assessors were not located at any clinical site. The secondary outcomes were based on the QIDS-SR collected at baseline and at each treatment visit.

An automated, telephonic, interactive voice response system

(7,

50–52) was used to collect ratings on the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey

(53) (perceived physical functioning and mental health functioning), the 16-item Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire

(54), the Work and Social Adjustment Scale

(55), and the 5-item Work Productivity and Activity Impairment

(56).

Intervention and Measurement-Based Care

Citalopram was selected as a representative SSRI given the absence of discontinuation symptoms, demonstrated safety in elderly and medically fragile patients, once-a-day dosing, few dose adjustment steps, and favorable drug-drug interaction profile

(7,

36). The aim of treatment was to achieve symptom remission (defined as QIDS-C score ≤5 collected at each treatment visit for the purposes of clinical decision making). The protocol

(7,

36) required a fully adequate dose of citalopram for a sufficient time to ensure that the likelihood of achieving remission was maximized and that those who did not reach remission were truly resistant to the medication.

The treatment protocol was designed to provide an optimal dose of citalopram based on dosing recommendations in a treatment manual (www.star-d.org) that also allowed individualized starting doses and dose adjustments to minimize side effects, maximize safety, and optimize the chances of therapeutic benefit for each patient. Medication management was assisted by ratings of symptoms (QIDS-C completed by the clinical research coordinator) and side effects (ratings of frequency, intensity, and burden)

(7) obtained at each treatment visit. Citalopram was started at 20 mg/day and then raised to 40 mg/day by week 4 and to 60 mg/day (final dose) by day 42 (week 6). Dose adjustments were based on how long a subject had received a particular dose, symptom changes, and side effect burden. However, appropriate flexibility was allowed, including initiation of citalopram at <20 mg/day or a slower dose escalation to the optimal target dose of 60 mg/day, so that patients with concomitant general medical disorders, substance abuse/dependence, or other psychiatric disorders could be included safely in the sample.

The protocol recommended treatment visits at 2, 4, 6, 9, and 12 weeks (with an optional week-14 visit if needed). After an optimal trial (based on dose and duration), remitters and responders could enter the 12-month naturalistic follow-up, but all responders who did not achieve remission were encouraged to enter the subsequent randomized trial. Patients could discontinue citalopram before 12 weeks if 1) intolerable side effects required a medication change, 2) an optimal dose increase was not possible because of side effects or participant choice, or 3) significant symptoms (QIDS-C score ≥9) were present after 9 weeks at maximally tolerated doses. Patients could opt to move to the next treatment level if they had intolerable side effects or if the QIDS-C score was >5 after an adequate trial in terms of dose and duration.

A treatment manual (including the treatment protocol and procedures), initial didactic instruction, ongoing support and guidance by the clinical research coordinator, the use of structured evaluation of symptoms and side effects at each visit, and a centralized treatment monitoring and feedback system, together, represented an intensive effort to provide consistent, high-quality care (www.star-d.org)

(52). To enhance the quality and consistency of care, physicians used the clinical decision support system that relied on the measurement of symptoms (QIDS-C and QIDS-SR), side effects (ratings of frequency, intensity, and burden), medication adherence (self-report), and clinical judgment based on patient progress. A web-based treatment monitoring system provided feedback to clinical research coordinators regarding the fidelity to the treatment recommendations for each patient. The clinical research coordinators could then help guide physicians in vigorously dosing when inadequate symptom reduction had occurred despite acceptable side effects

(7).

Safety Assessments

Side effects were evaluated with the ratings of frequency, intensity, and burden completed by patients at each treatment visit

(7). Three 7-point subscales measure the frequency, intensity, and global burden of side effects.

Serious adverse events were monitored with a multitiered approach involving the clinical research coordinators, study clinicians, the interactive voice response system, the clinical manager, safety officers, regional center directors

(57), and the NIMH Data Safety and Monitoring Board.

Concomitant Medications

Concomitant treatments for current general medical conditions (as part of ongoing clinical care), for associated symptoms of depression (e.g., sleep, anxiety, and agitation), and for citalopram side effects (e.g., sexual dysfunction) were permitted on the basis of clinical judgment. Stimulants, anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, alprazolam, nonprotocol antidepressants (except trazodone ≤200 mg at bedtime for insomnia), and depression-targeted psychotherapies were proscribed.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics of the demographic, social, and clinical characteristics are presented for the analyzable sample of 2,876 patients. Summary statistics of treatment characteristics (e.g., maximum dose achieved, number of treatment visits), serious adverse events, and side effects are presented for the entire sample and by remission status. Logistic regression models assessed the association of the demographic, social, and clinical characteristics with remission, independent of the effect of regional center and baseline depression severity. As a subsequent analysis designed to assess the unique and independent contribution of these variables to remission rates, a stepwise logistic regression model was developed with both the HAM-D and the QIDS-SR. This model identified baseline features associated with remission independent of baseline depression severity and regional center, both within the three domains (demographic, social, and clinical) and across all three domains.

Remission was defined as an exit HAM-D score ≤7 (or last observed QIDS-SR score ≤5). A reduction of ≥50% in baseline QIDS-SR at the last assessment was defined as response. Intolerance was defined a priori as either leaving treatment before 4 weeks or leaving at or after 4 weeks with intolerance as the identified reason. As defined by the original proposal, patients were designated as not achieving remission when their exit HAM-D score was missing. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine whether this method of addressing missing data affected study results. Two additional methods also addressed missing data in the analysis of remission based on HAM-D scores: 1) a multiple imputation method and 2) an imputed value generated from an item response theory analysis of the relationship between the HAM-D and the QIDS-C. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided p value less than 0.05. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons, so results must be interpreted accordingly.

Results

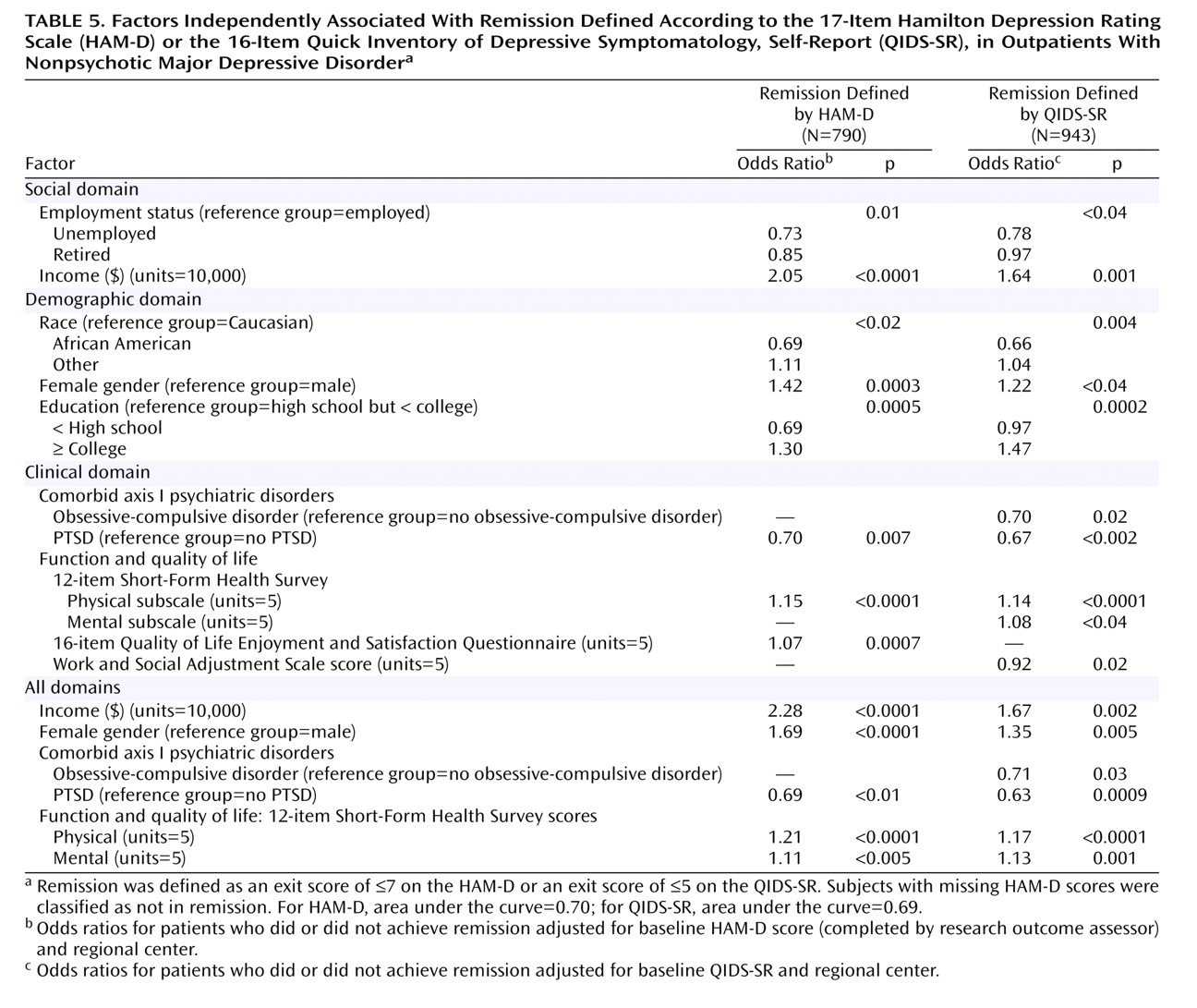

Figure 1 shows the disposition of patients during the course of the study.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

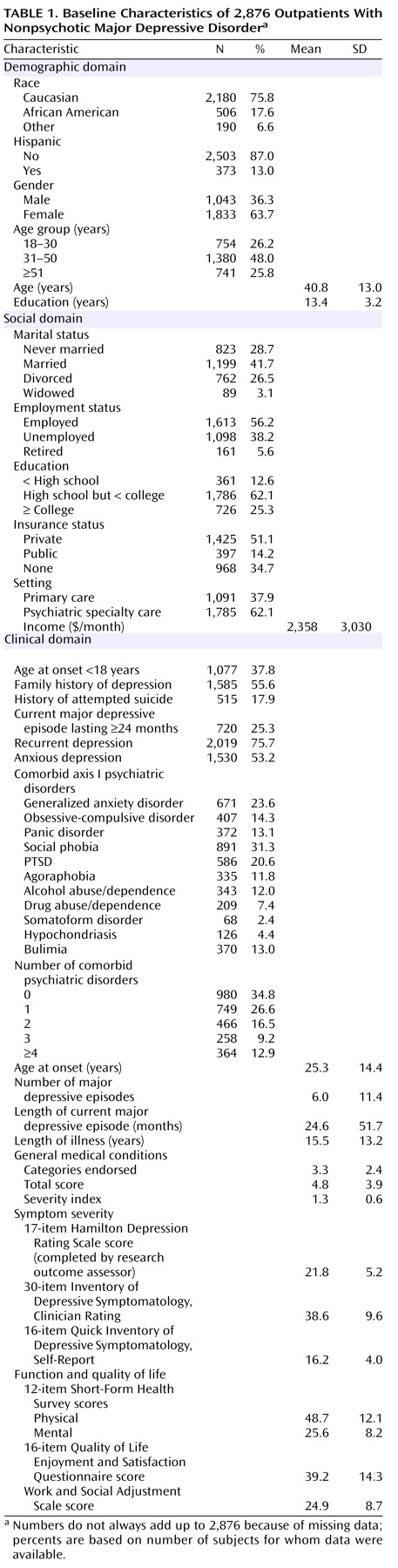

Table 1 summarizes the baseline features of the evaluable sample (N=2,876). The patients included in the evaluable sample did not differ from those excluded on any of the characteristics in

Table 1 (data not shown). About 62% of the participants were from psychiatric care settings. Minority representation was 24%. Depressive symptoms were moderate to severe (HAM-D >21). More than 75% of the patients met DSM-IV criteria for recurrent or chronic depression. The mean length of illness was 15.5 years (time from onset of first major depressive episode to study entry). At study entry, subjects had an average of 3.3 general medical conditions.

Treatment Features

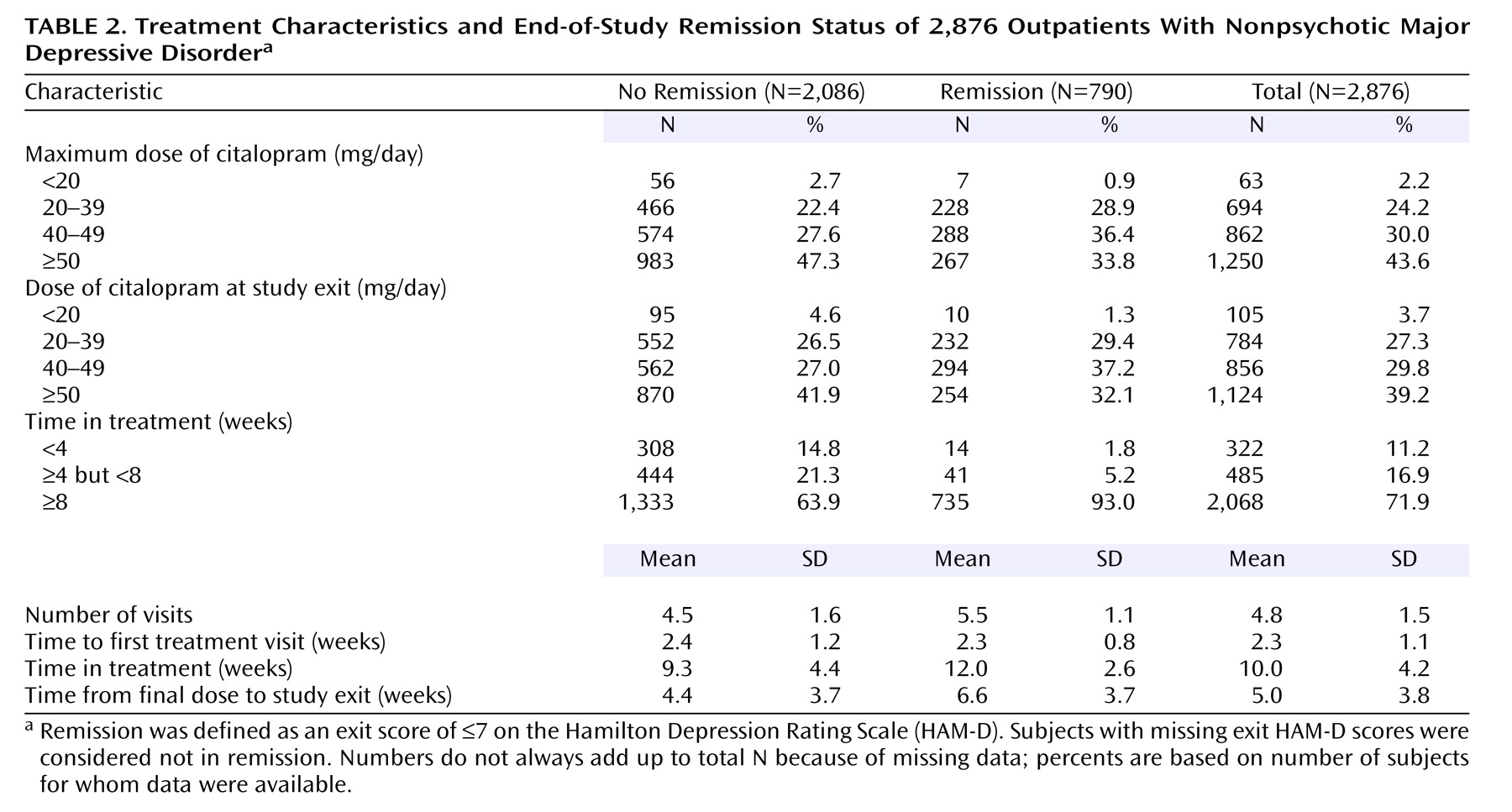

The study protocol recommended five postbaseline visits with an optional sixth visit (for those with meaningful improvement short of remission). Overall, participants averaged 4.8 visits (SD=1.5) (

Table 2). Those who met HAM-D remission criteria had 5.5 visits (SD=1.1), and those who did not averaged 4.5 visits (SD=1.6). The time from baseline to the next treatment visit (for both remitters and nonremitters) was slightly over 2 weeks, which was within the recommended visit schedule.

Citalopram treatment averaged 10 weeks (SD=4.2, median=11.6) or 70.2 days (SD=29.2, median=81). Patients who achieved HAM-D remission remained in treatment for a mean of 12 weeks (SD=2.6) (mean=83.8 days, SD=18.1). Almost all (93%) of these patients completed at least 8 weeks, as opposed to only 64% of the patients who did not achieve remission (

Table 2).

The mean exit dose of citalopram (41.8 mg/day, SD=16.8) was comparable for patients who did or did not achieve remission. Doses in primary care settings (40.6 mg/day, SD=16.6) and psychiatric care settings (42.5 mg/day, SD=16.8) were comparable.

Symptomatic Outcomes

The overall remission rate was 27.5% (N=790) with the HAM-D definition (primary outcome) and 32.9% (N=943) with the QIDS-SR definition. Remission rates were comparable in primary and psychiatric care for the HAM-D (26.6% versus 28.0%) and the QIDS-SR (32.5% versus 33.1%). The overall QIDS-SR response rate was 47% (N=1,343) (46% primary care, 48% psychiatric care).

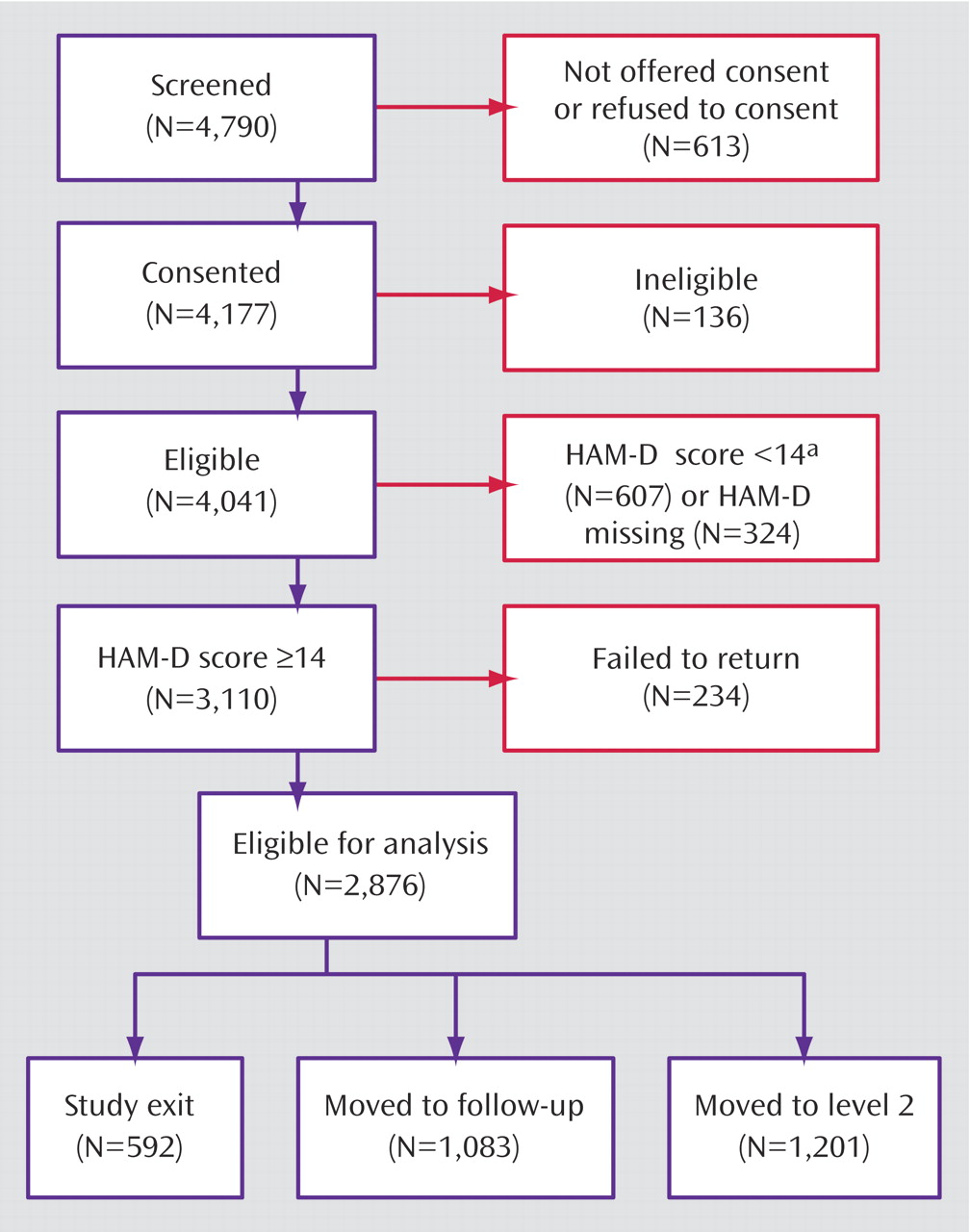

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the exit QIDS-SR scores. A QIDS-SR score of 10 approximates an HAM-D score of 13

(45).

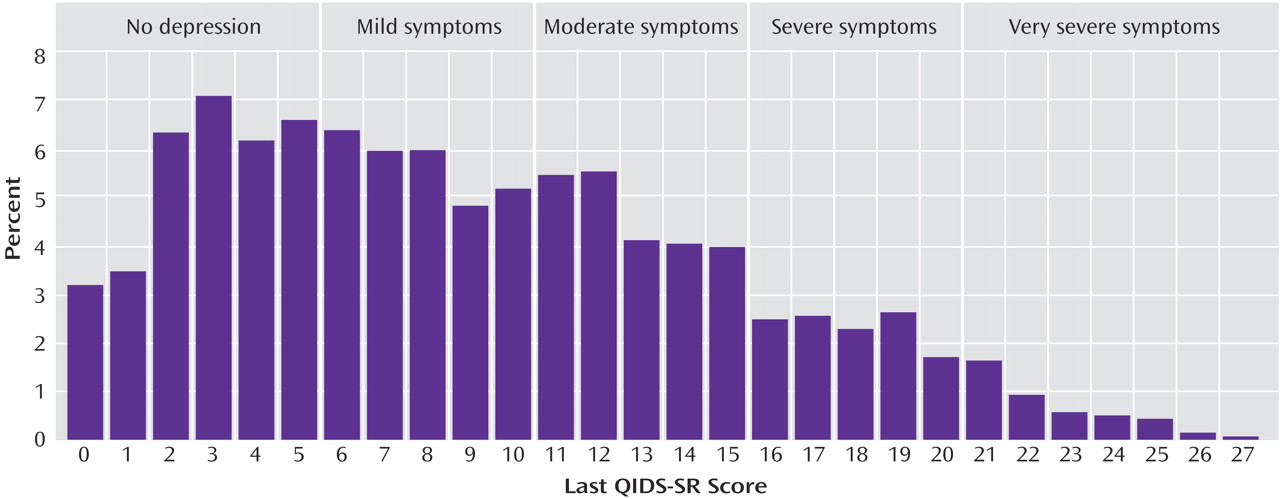

Figure 3 shows the distribution of the time to first remission and response for those who ultimately did achieve remission and response in this study based on QIDS-SR scores. For those who achieved QIDS-SR remission, the mean time to remission was 6.7 weeks (SD=3.8) and was comparable in primary care (approximately 6 weeks) and psychiatric care (approximately 7 weeks). For those who achieved a QIDS-SR response, the mean time to response was approximately 5.7 weeks (SD=3.5) and was comparable in primary care (mean=5.7 weeks, SD=3.7) and psychiatric specialty care (mean=5.6 weeks, SD=3.5).

For those who achieved remission according to QIDS-SR scores, the mean time in treatment was approximately 12 weeks (SD=3).

Intolerance and Adverse Events

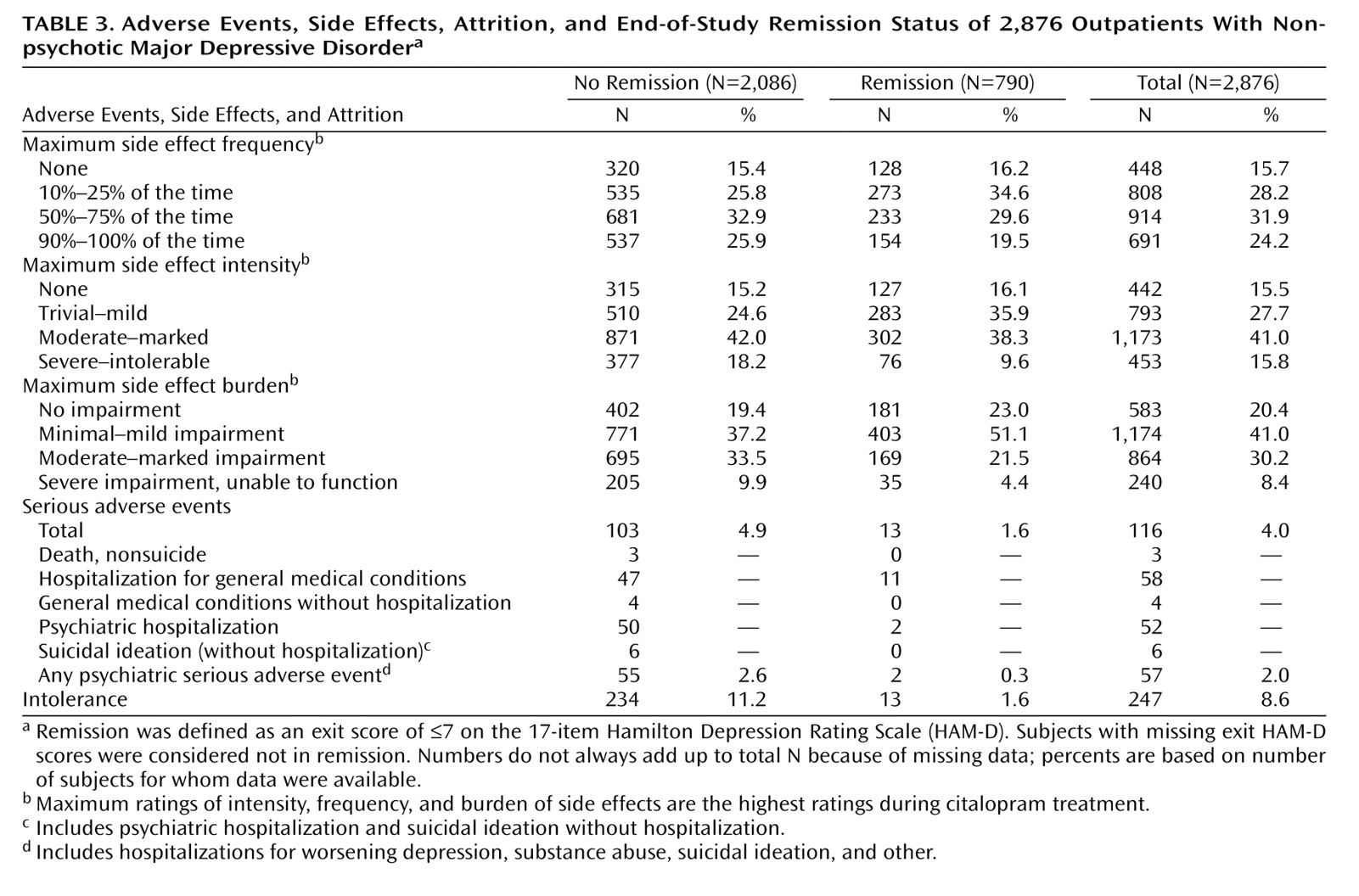

Only 2% of the patients who achieved HAM-D remission were considered to have discontinued citalopram because of intolerance, compared with 11% of those who did not achieve HAM-D remission (

Table 3). Those who achieved HAM-D remission had lower rates of side effect frequency, intensity, and burden at exit and lower rates of serious adverse effects than those who did not achieve HAM-D remission. Overall, 116 participants experienced at least one serious adverse effect; most of these patients (88.8% [N=103]) did not achieve HAM-D remission. There were no suicides in the 2,876 participants in this acute-phase citalopram study.

Pretreatment Correlates of Remission

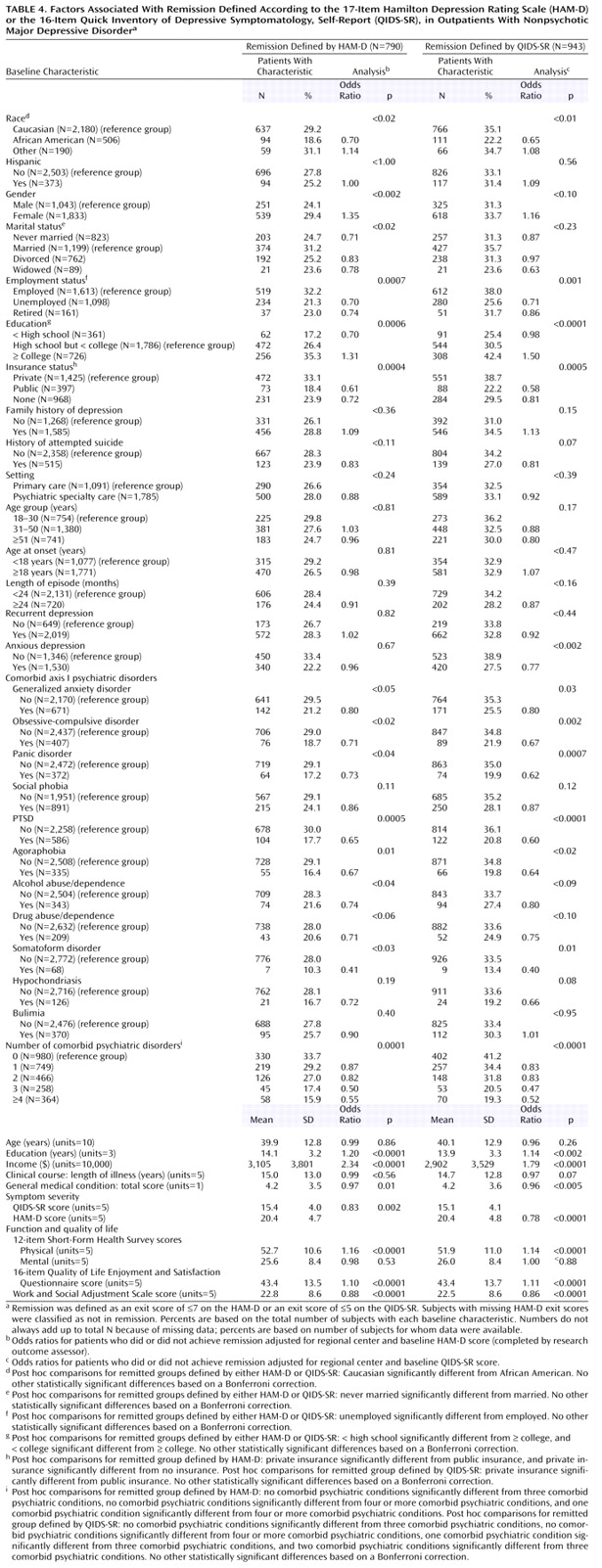

Several pretreatment demographic, social, and clinical features were associated with remission based on either the HAM-D or QIDS-SR following adjustments for baseline symptom severity and regional center (

Table 4). Findings were almost identical for the HAM-D and the QIDS-SR except that anxious depression and concurrent generalized anxiety disorder were also associated with lower QIDS-SR remission rates.

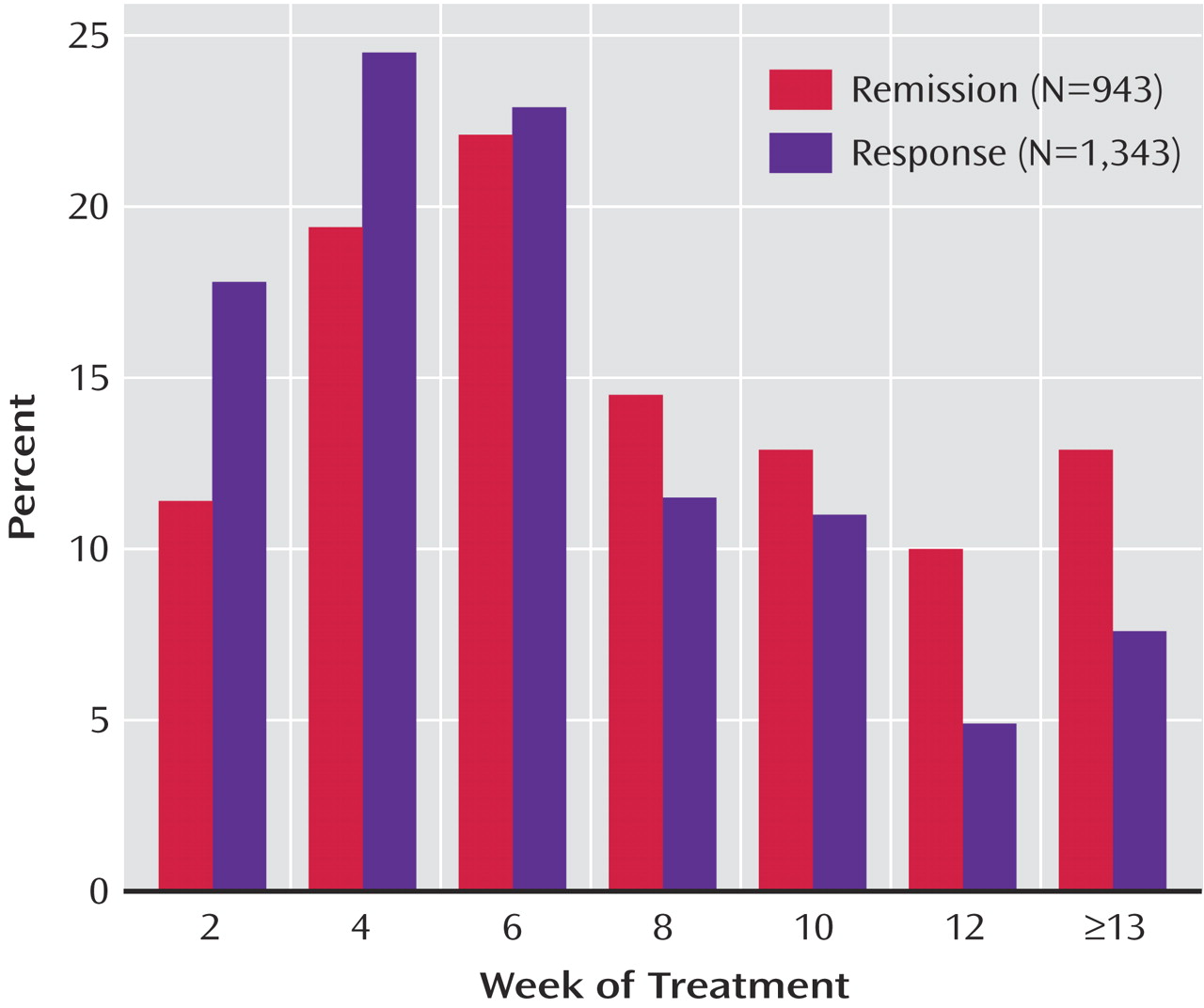

Table 5 presents pretreatment features that were nonoverlapping and independently associated with remission after baseline depressive symptom severity and regional center for each domain separately and across all domains were controlled for. Lower remission rates were associated with being unemployed; having a lower income; being non-Caucasian, male, and less educated; and having poorer function and lower quality of life at baseline. Remarkably consistent findings were obtained with the HAM-D and the QIDS-SR.

Discussion

Results of this study should be generalizable to routine clinical practice because this is the largest ecologically valid “real world” study of outpatients with nonpsychotic major depressive disorder treated in psychiatric and primary care settings with diligently followed guidelines. Participants in the study were patients seeking treatment in “real world” clinical practices who had high rates of chronic or recurrent major depressive disorder and concurrent axis I and axis III (general medical conditions) disorders. Since there were very broad inclusion criteria and few exclusion criteria, this study included patients who would have been excluded from most efficacy trials

(58–

61).

The remission rates (28% for HAM-D; 33% for QIDS-SR) were robust and similar to rates found in uncomplicated, nonchronic symptomatic volunteers enrolled in placebo-controlled, 8-week, randomized, controlled trials with SSRIs

(4). These remission rates were better than those found in efficacy studies among patients with chronic depression (22%)

(9), possibly because of a number of factors discussed below, including the use of measurement-based care and the clinical research coordinators.

Higher remission rates were found with the QIDS-SR than with the HAM-D because our primary analyses classified patients with missing exit HAM-D as nonremitters a priori. Of the 690 patients with missing exit HAM-D scores, 152 (22.1%) achieved QIDS-SR remission at the last treatment visit.

As described earlier, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the methods used to address the missing HAM-D data. Both the multiple imputation approach and the use of values imputed from the observed exit QIDS-C score based on item response theory revealed remarkably similar findings, indicating that the analyses were not affected by the missing data methodology.

Of participants who responded, 56.0% did so only at or after 8 weeks of treatment. Not surprisingly, remission followed response in most cases. Of those who achieved QIDS-SR remission, 40.3% did so only at or after 8 weeks of citalopram.

Results also highlight the feasibility, safety, tolerability, and effectiveness of delivering high-quality care with easy-to-use clinical methods employed at each treatment visit to ensure adequate treatment delivery (measurement-based care approach). The approach may have contributed to the better-than-expected remission rates in this group of patients as well, although a firm conclusion cannot be made without a control group. On the other hand, several controlled studies

(10,

14,

62) suggest a clear benefit for a disease management approach in the comprehensive treatment of depression. These studies have emphasized more frequent patient contact as well as more robust psychosocial and educational support to enhance adherence, improve patients’ ability to monitor their own symptoms, and help patients understand the nature of and treatment needs for their depression.

Unlike previous studies

(10,

14,

62), this study used pharmacotherapy augmented with diligent measurement-based procedures employing easy-to-use ratings of symptoms and side effect frequency, intensity, and burden, as well as triage points with dosing recommendations that allowed necessary flexibility. This measurement-based care approach represents a paradigm shift to the use of easily employed research tools in clinical practice. Tools used in research settings (e.g., HAM-D or other measures of symptoms, function, or side effects) are not routinely used in practice, which may contribute to the high rates of inadequate treatment with antidepressant medications in routine care

(12). Our results also suggest that the use of depressive symptom and side effect ratings (www.ids-qids.org) to guide treatment is feasible in “real world” practices as well as effectiveness trials and can be used to monitor patient progress, to adjust the treatment, and to make clinical decisions. In this study, adequate citalopram doses and treatment duration were achieved with a structured yet flexible dosing schedule.

Several baseline features were associated with higher remission rates, including lower baseline severity; being Caucasian, female, better educated, and more highly paid; and having private insurance, fewer concurrent general medical and psychiatric disorders, better pretreatment physical and mental function (12-item Short-Form Health Survey physical and mental subscales), greater life satisfaction, and a shorter current episode. Taken together, greater illness severity and psychiatric and general medical comorbidity as well as less social support are likely associated with lower remission rates for citalopram. These findings are consistent with some of the previous studies that reported lower response rates to antidepressants in subjects with greater baseline symptom severity and longer current episodes

(19,

25,

63–67).

Our sample size was large enough to identify a number of clinically relevant features in developing a model to predict remission for major depressive disorder even after controlling for both severity and treatment settings. These results do not address whether similar or different baseline features would be negatively associated with remission for other antidepressant medications or whether results would differ for psychotherapy or combination(s) of antidepressant treatments.

In our sample, being married or living with someone appeared to have a positive effect on the overall remission rates; married or cohabiting patients met criteria for treatment response with greater frequency than single participants. Although Hagerty and Williams

(68) found that patients living alone were more likely to drop out of treatment, our findings indicate that participants who were unmarried or living alone did not drop out early and yet had lower remission rates. Not all studies have found social support to be a significant predictor of treatment outcome

(69,

70), but most have suggested social support and, even more specifically, marital status as positive predictors of response.

Study limitations include open treatment design, the use of a single antidepressant agent (citalopram), and the lack of placebo control. Nonspecific treatment effects undoubtedly accounted for some unknown proportion of the acute response or remission rates

(71). Additional studies with other antidepressant medications are needed to determine whether the current findings are generalizable to other medications.

These results highlight the need for longer treatment duration and more vigorous medication dosing than is current practice in order to achieve optimal remission rates. Informed triage or critical decision points (i.e., the discontinuation of patients who experience minimal benefit after 6–9 weeks of treatment) allow for extended dosing for those who are benefiting, while curtailing extended treatment for those who experience minimal benefit after a substantial treatment period. The measurement-based care methods used in this study were easily implemented in actual practice. Controlled trials of this approach in practice are recommended.