The subject of bipolar disorder among the elderly has received little empirical attention. A recent report from the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance

(1) singled out this area as one in need of further study. An exhaustive systematic review of bipolar disorder among the elderly by Depp and Jeste

(2) yielded few data from epidemiological community surveys. Limitations of previous work include a lack of standardized diagnostic measures, the biases inherent in retrospective chart reviews, and an overemphasis on inpatients.

The most common comorbidities among young and middle-age adults with bipolar disorder are substance use disorders and anxiety disorders

(3). However, data regarding psychiatric comorbidity among elderly people with bipolar disorder are sparse. In a small study of elderly men with bipolar disorder, 29% of the subjects had comorbid axis I disorders

(4). Another study

(5) reported comorbid substance use disorders in 29% of the bipolar disorder respondents who were older than 60. Data regarding the presence of anxiety disorders or other psychiatric disorders among elderly individuals with bipolar disorder are essentially absent from the literature

(2).

There is, however, a body of literature that suggests that anxiety disorders are less common among the elderly in general

(6). Panic disorder is considered especially rare in old age. Reasons for this replicated finding include disorder-associated mortality and age-related changes in brain neurochemistry (as evidenced by decreased responsiveness to cholecystokinin tetrapeptide [CCK-4] challenge)

(7).

Data from a large-scale epidemiological community survey are needed to address this underresearched area, particularly because of the low prevalence of bipolar disorder among the elderly. A priori hypotheses were that alcohol use disorders, dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder would be more prevalent among elderly individuals with bipolar disorder as compared to elderly individuals without bipolar disorder and less prevalent as compared to young and middle-aged adults with bipolar disorder.

Method

Subjects were identified from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), 2001–2002. Details of the NESARC, conducted by the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (NIAAA), are described in detail elsewhere

(8). Briefly, a nationally representative sample of 43,093 respondents, 18 years and older, completed face-to-face computer-assisted personal interviews. The target population of the NESARC is the civilian noninstitutionalized population residing in the United States, including Alaska and Hawaii. The overall survey response rate was 81%. From the overall sample, 8,121 nonbipolar respondents ≥65 years of age, 1,327 respondents <65 with bipolar disorder, and 84 respondents ≥65 years of age with bipolar disorder were selected for the purpose of analyses.

The NIAAA Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV has established reliability and validity for diagnosing mood, anxiety, and alcohol use disorders

(8–

11). The reliability of the bipolar disorder diagnosis (kappa=0.59) is fair

(9). The reliability of the comorbid diagnoses reported here ranged from kappa=0.41 for past-year generalized anxiety disorder to kappa=0.70 for lifetime alcohol use disorders

(10–

11).

The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV explicitly addresses the temporal contiguity of manic episodes with substance use and general medical conditions when present. Only independent cases of bipolar disorder were included.

One-way analysis of variance was used to compare differences between groups on dimensional measures. Cross-tabulations were used to compare categorical measures.

Results

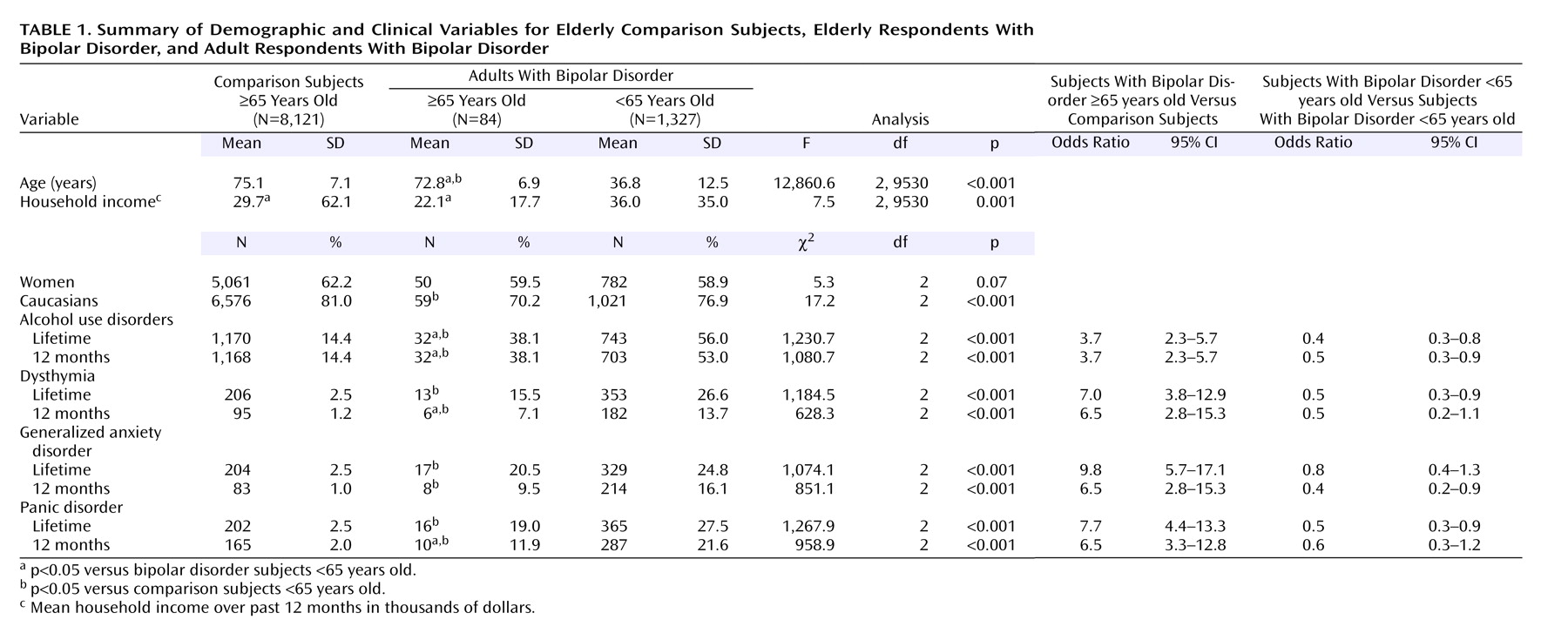

Eighty-four elderly respondents with bipolar I disorder were identified from the overall sample of 43,093 NESARC respondents. The prevalence of bipolar disorder among elderly respondents was approximately 1%. Of these, 50 (59.5%) were women and 34 (40.5%) were men. Elderly respondents with bipolar disorder differed from young and middle-age adults with bipolar disorder and from elderly respondents without bipolar disorder on several demographic and clinical variables (

Table 1).

Compared with elderly respondents without bipolar disorder, elderly respondents with bipolar disorder were slightly younger and less likely to be Caucasian but were of comparable socioeconomic status. Elderly respondents with bipolar disorder endorsed higher lifetime and 12-month prevalence rates of each axis I disorder examined: alcohol use disorders, dysthymic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder.

Elderly respondents with bipolar disorder had lower prevalence rates of lifetime and 12-month alcohol use disorders than younger respondents with bipolar disorder. Contrary to the study hypotheses, the lifetime prevalence of dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder did not differ significantly from that of the younger respondents with bipolar disorder.

Because of the known contribution of gender to variability in adult mood disorders and substance use disorders, secondary analyses comparing men and women were conducted. More men met criteria for an alcohol use disorder (N=23, 67.6%) than women (N=9, 18%; odds ratio=9.5, 95% confidence interval [CI]=3.4–26.4, p<0.001). There was no significant sex difference in the lifetime or 12-month prevalence of dysthymia or in the lifetime prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder. However, the 12-month prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder among women (N=8, 16.0%) was significantly greater than among men (N=0, 0%). Women, compared to men, had significantly greater lifetime (N=9, 28.0%, versus N=2, 5.9%) and 12-month (N=4, 18.0%, versus N=1, 2.9%), prevalence of panic disorder than men (odds ratio=3.3, 95% CI=0.7–16.4, p=0.01, and odds ratio=2.9, 95% CI=0.3–26.9, p=0.04, respectively).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report describing axis I comorbidity in an epidemiological community sample of elderly individuals with bipolar disorder. Furthermore, the results of this study provide compelling evidence that the known strong association between panic disorder and bipolar disorder

(12) does not attenuate in old age.

As expected, a greater proportion of elderly respondents with bipolar disorder reported comorbid alcohol use disorders, dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder compared to elderly respondents without bipolar disorder. Contrary to the study’s hypotheses, no significant differences were observed in the lifetime prevalences of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder among elderly compared to younger individuals with bipolar disorder. Such a difference in the lifetime prevalence of these anxiety disorders could be expected based on the limited available evidence from general population samples

(6–

7). The high 12-month prevalence of alcohol use disorders among both elderly bipolar men and women implies that screening for alcohol use disorders should be standard for bipolar patients of all ages.

This study’s primary limitation is that despite the large overall sample, only 84 elderly bipolar disorder respondents were identified. In addition, this study did not include institutionalized individuals. Given that comorbid cognitive impairment and neurological disorders are both common among elderly individuals with bipolar disorder

(13) and frequently associated with institutionalization, the prevalence of bipolar disorder among the elderly is likely to be higher than the data suggest.

Taken together, these findings provide confirmatory evidence that bipolar disorder in old age remains a severe illness frequently characterized by comorbid disorders with their attendant burden and risk. Future studies are needed to corroborate these findings and to evaluate the ongoing dynamic between comorbidity and outcome across time.