Case Studies

Of the 10 studies that met inclusion criteria for review

(12 –

21), seven reported delayed-onset PTSD in relation to war experiences

(14 –

17,

19 –

21) and three in relation to motor vehicle accidents

(12,

13,

18) . Four of the studies used DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, which include clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or important areas of functioning (criterion F). Close inspection of the text indicated clear evidence of impairment in all studies, including the six that used earlier versions of DSM in which the diagnostic criteria did not require impairment. Overall, the war experience articles described 23 cases, with 15 accounted for by one article

(20) . With one exception

(21), the cases were of elderly veterans of World War II or the Korean War (age range=63–86 years) with PTSD onsets delayed by at least 30 years. The young soldier described by Solomon et al.

(21) had an onset around 12 months after his tour of duty. In contrast, all four patients described in the articles on motor vehicle accident trauma were younger (age range=23–45 years) and had onset delays ranging from 10 months to 4 years. The most convincing evidence for delayed-onset PTSD was from three motor vehicle accident victims who were under continuing medical care for their physical injuries prior to onset, making detection of symptoms in the posttrauma period more likely if present

(12,

13) . In the six studies describing elderly war veterans with very long intervals to first onset, 18 of the 22 cases were corroborated by someone else, in most cases a relative and usually the spouse

(15,

19,

20) . Given the age of the veterans, this does not rule out the possibility of episodes in the early months or years posttrauma that might have gone undisclosed or been forgotten, a limitation noted in two studies

(20,

15) . The corroborative evidence suggests at least that the veterans in question had long relatively symptom-free periods before onset in old age.

All the case studies reported events or circumstances that could have triggered onset. More than half of the cases (15/27) were attributed to an onset of a physical illness in the elderly veterans

(14 –

16,

20) . With one exception

(16), all were neurological illnesses or conditions that may affect cognition. In nearly a quarter of the cases (6/27), the triggers described were reminders of the original trauma

(12,

14,

17,

18 ). Two examples were a subsequent near-miss accident experienced by a motor vehicle accident victim

(12) and a severe head injury to the son of a veteran who had himself sustained a head injury as part of his traumatic experiences

(14) . Details of these studies are included in a supplemental table in the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article.

Group Studies

In 13 of the 19 group studies, delayed onset could be defined as at least 6 months after trauma exposure. Four of these

(22 –

25) yielded data on the proportion of respondents for whom no posttraumatic symptoms at all were observed in this period (corresponding to definition 1 of delayed-onset PTSD above), whereas the other nine studies reported the proportion of people who met full criteria for PTSD only after this period (corresponding to definition 2 above). In the remaining six studies, delayed onset of full PTSD could be defined as 1 year or more after trauma exposure (also corresponding to definition 2). It is notable that only two of the 19 studies

(26,

27) used DSM-IV, which includes criterion F—clinically significant distress/impairment—and both studies appear to have assessed it, although this was not explicitly stated. Studies using earlier editions of DSM were not required to assess criterion F, and none reported any relevant data.

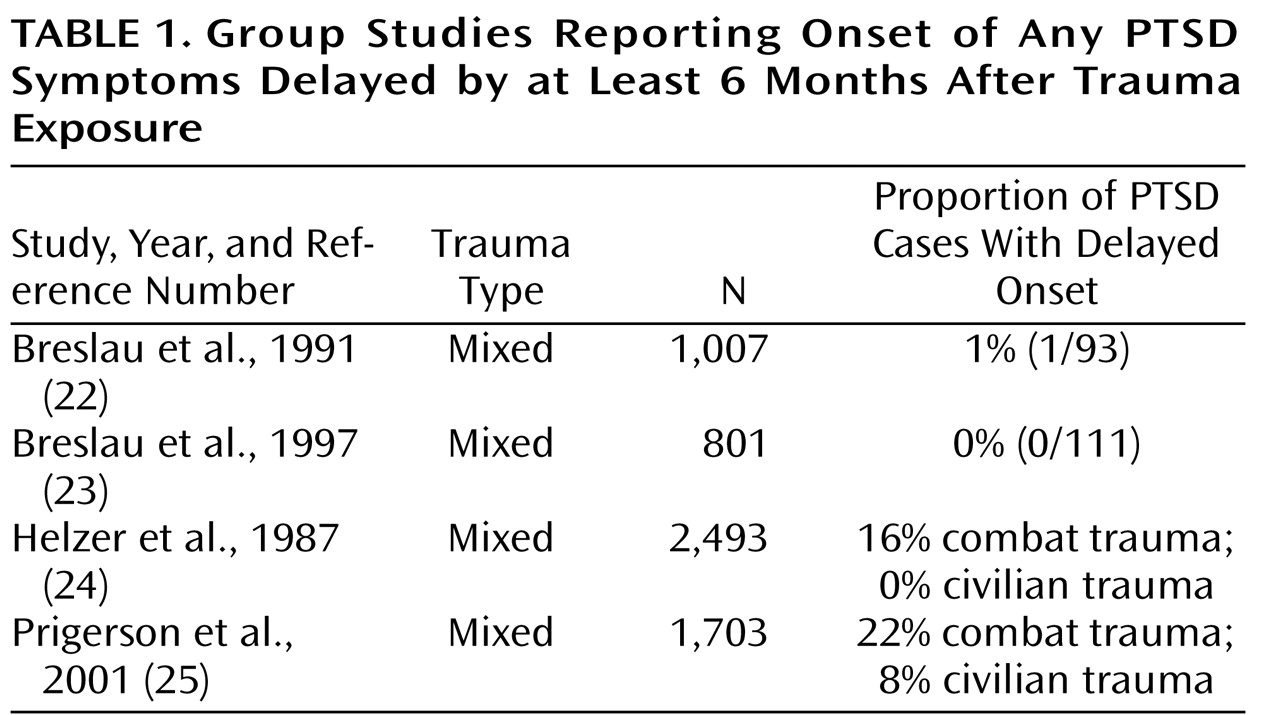

Of the four studies that provide evidence relevant to definition 1 (

Table 1 ), two report the number of respondents with full PTSD

(23,

24), and two report the numbers of respondents with both syndromal or subsyndromal PTSD after 6 months

(24,

25) . Of all the group studies reviewed, these were the only ones to include subsyndromal cases. In the Prigerson et al. study

(25), 37 of the 172 PTSD cases (22%) were subsyndromal. The majority met all DSM-III-R symptom cluster criteria but did not meet the symptom duration criterion (Maciejewski, personal communication, 2006). In the Helzer et al. study

(24), PTSD was rare, and nearly all (94%) of the 422 cases were subsyndromal, defined as having any PTSD symptoms. All of these studies are distinguished from other group studies reviewed inasmuch as they are epidemiological investigations of a variety of traumas with varying lengths of time between trauma and assessment. Given that all used retrospective interviews, it was assumed that earlier, now remitted onsets were taken into account in the assessment. Helzer et al.

(24) and Prigerson et al.

(25) reported higher rates of delayed symptom onset in combat trauma than in civilian traumas. In the Helzer et al. study, there were no delayed symptom onsets among those with civilian traumas. In two studies, Breslau and colleagues

(22,

23) similarly found minimal or no evidence of delayed onset in studies of young mothers and of adults too young to have been Vietnam conscripts.

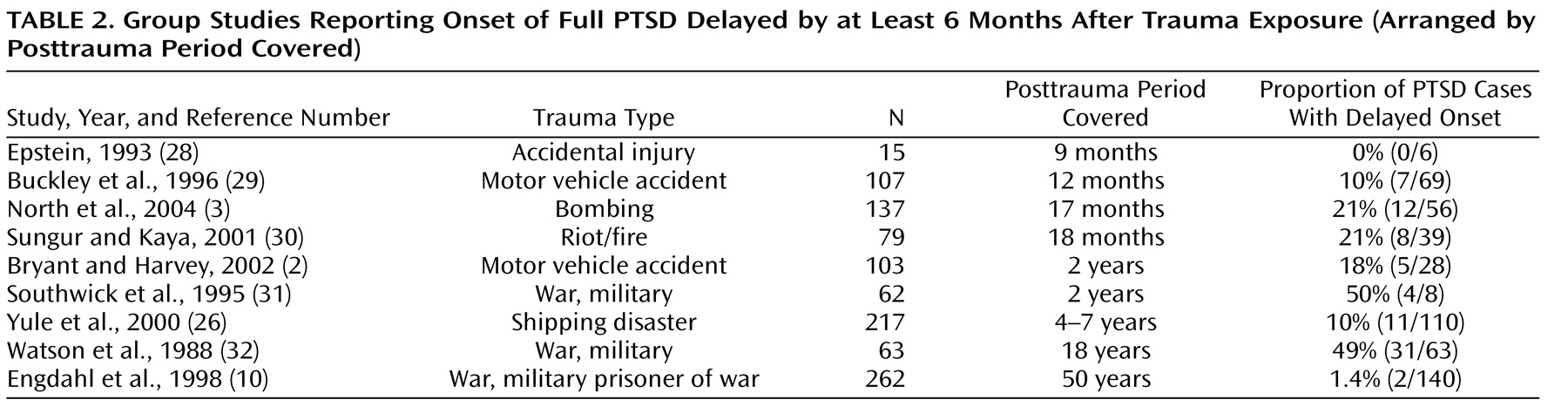

Table 2 presents details of the nine studies

(2,

3,

10,

26,

28 –

32) in which onset of full PTSD was delayed by at least 6 months. Studies are arranged by the length of the period covered after trauma exposure, which ranged from 9 months to 50 years. Six were longitudinal and the three with the longest assessment periods were retrospective in design. With one exception

(31), all used clinical interviews to assess PTSD. We looked for factors that might affect the rates of delayed-onset PTSD, the first being the length of the posttrauma assessment period, on the assumption that the longer the period assessed beyond the first 6 months, the more opportunity there would be for respondents to develop delayed-onset PTSD.

Table 2 shows that with two exceptions

(10,

26), the pattern of delayed onset rates broadly fitted our assumptions. The study with the shortest period covered, 9 months

(28), found no onsets delayed by more than 6 months. It should be noted that the Yule et al. study

(26) differed from the others in that the respondents were schoolchildren at the time of the trauma. Also notable is that two of the three studies with military samples reported similar delayed-onset rates that were much higher than the civilian studies

(31,

32) despite differences in study design and duration. However, the Engdahl et al. retrospective investigation

(10) of veterans who were all prisoners of war is inconsistent with this pattern. These authors found only two cases of delayed onset in 140 PTSD cases.

Another factor considered was whether the studies assessed whether respondents could have had onsets of PTSD that then remitted before the next assessment point. As noted, lack of such an assessment could lead to both over- and underestimates of delayed-onset rates. We investigated whether the studies assessed remitted onsets between time points as well as whether earlier episodes of PTSD within 6 months of the trauma could be ruled out. Three of the longitudinal studies were negative on both counts

(2,

30,

31), but this did not appear to affect the delayed-onset rates relative to the other studies that had included these assessments. For example, both North et al.

(3) and Sungur and Kaya

(30), with similar study durations, reported delayed-onset rates of 21%, although only the former assessed symptoms between time points. One possible explanation is that the under- and overestimates that might be a consequence of assessment omissions cancel each other out.

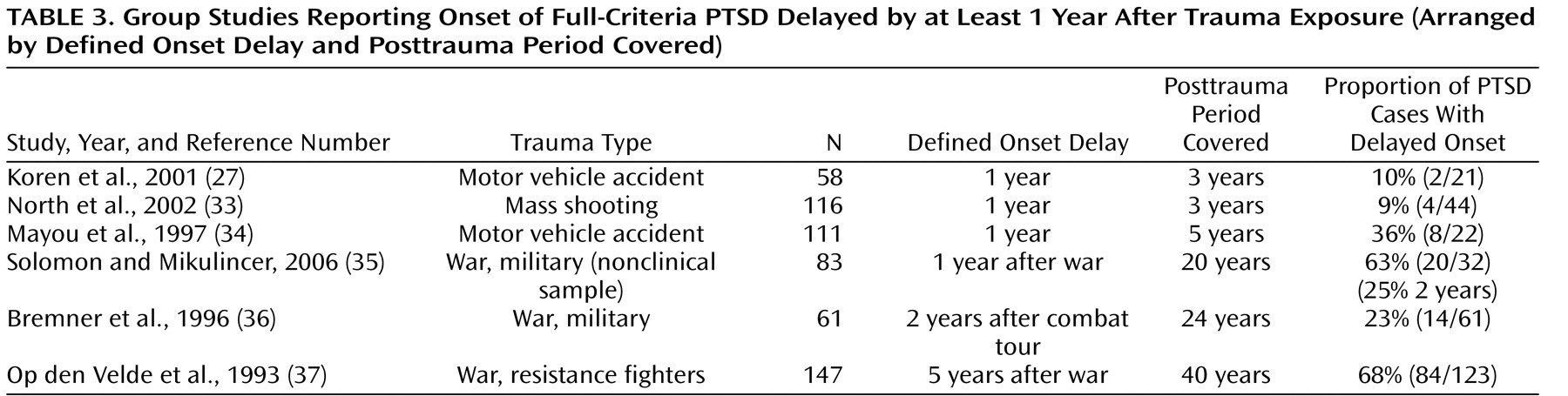

Table 3 lists the six studies

(27,

33 –

37) in the final category, in which onset of full PTSD was delayed by at least 1 year after trauma exposure. Four of these studies were longitudinal, and these all defined delayed onset as 1 year after trauma exposure

(27,

33 –

35) . The remaining two studies were retrospective and defined onset delay as 2 years

(36) or 5 years after trauma exposure

(37) . The posttrauma period covered ranged from 3 years to 40 years in the six studies. Three studies were of war-related trauma and included two military samples

(35,

36) and a sample of resistance fighters

(37) . The other three involved motor vehicle accidents

(27,

34) and a mass shooting

(33) . As with the studies listed in

Table 2, it was expected that the longer the posttrauma period covered, the higher the delayed-onset rate would be. However, this trend might be moderated by the defined posttrauma delay: the longer the delay, the lower the likelihood that delayed onsets would develop subsequently.

The four longitudinal studies with delayed onset defined as 1 year after trauma exposure confirmed the pattern found in the 6-month delayed-onset studies—the longer the period covered, the higher the rate of delayed onsets. The two studies covering a 3-year period after trauma exposure

(27,

33) had similar delayed-onset rates despite the fact that prior episodes were not ruled out in one of the studies

(27) . Solomon and Mikulincer

(35), with the longest period covered (20 years) of the four studies defining delay as at least 1 year, reported a particularly high rate of 63% in Israeli combat veterans assessed as having no combat stress reaction during the 1982 Lebanon war. This study is of particular interest, as it had four assessment points, at 1, 2, 3, and 20 years, and reported delayed-onset rates at each time point. The study showed that the majority of delayed onsets (12 of 20) occurred in the relatively brief interval between 1 and 2 years after exposure. It was possible to compare this study with the Bremner et al. investigation

(36) of U.S. war veterans, which used a retrospective interview to cover a similar period and had delayed onset defined as 2 years after exposure. As shown in

Table 3, the 2-year rates of delayed onset, expressed as a proportion of all PTSD cases, were remarkably similar (25% and 23%).

The last study in this category is that of Op den Velde et al.

(37), who reported that about two-thirds of all PTSD cases in their sample of Dutch World War II resistance fighters were delayed by as much as 5 years. This investigation used a retrospective clinical interview. The authors distinguished PTSD onsets that gradually developed from an earlier subsyndromal condition from delayed PTSD in which the first symptoms did not appear until at least 5 years after the war. It is of interest to contrast the delayed-onset rate in all PTSD cases in this study (84 of 123, or 68%) with that of Engdahl et al.

(10) (2 of 140, or 1.4%; see

Table 2 ), as both involved male combatants and used retrospective interviews to cover 40 years or more after trauma exposure (the longest posttrauma periods in the studies reviewed). The reason for the discrepancy is unclear. It cannot be explained by the element of captivity, as over half of the resistance fighters had been in concentration camps.

To summarize the frequency of delayed-onset PTSD for the six military and nine civilian studies in

Tables 2 and

3, we calculated the mean rates, weighting for sample size, length of delay, and length of follow-up period. The weighted means were 38.2% and 15.3%, respectively, for military and civilian studies. These were similar to the unweighted means (42.4% and 15%, respectively). Considering these 15 studies overall, eight reported information on prior symptoms, and in six of these, all cases of delayed onset had prior symptoms (information for reference

10 supplied by personal communication with first author, 2006). However, none of these studies systematically reported information to indicate how many symptoms were involved in the transition to full syndromal criteria.

Supplementary details of all 19 studies described in this section, including mean age, gender, and assessment, are available in a data supplement accompanying the online version of this article.