Bipolar disorder is a major public health problem with a high lifetime prevalence (≥1%) and substantial risk of long-term morbidity, comorbidity, and disability

(1 –

7) . Bipolar disorder also carries high rates of premature mortality due largely to suicide but including also the effects of accidents, substance abuse, and general medical disorders

(8) . Women with bipolar disorder encounter several obstacles to care with respect to pregnancy, including extraordinary knowledge gaps about the illness course during pregnancy, predictors of risk or protective factors for recurrence as well as reproductive safety data for various mood stabilizers

(9,

10,

11) . Currently, a common clinical practice is to stop ongoing mood stabilizing treatment during pregnancy in order to avoid potential adverse fetal developmental effects and purported associated liability risk

(12 –

15) . However, some progress has been made lately in applying the limited information available to develop treatment guidelines for the clinical management of women with bipolar disorder during pregnancy

(16 –

18) .

Whether pregnancy affects morbid risk favorably or unfavorably still remains uncertain

(17 –

20) . Most of the few available studies of pregnant women with bipolar disorder involve small case reports or retrospective analyses

(15,

21 –

28) . A few observations suggest that some bipolar disorder patients may remain euthymic during pregnancy after discontinuing mood stabilizing medication

(21 –

24) . For example, Grof and his colleagues

(24) suggested that pregnancy may exert a favorable effect on the course of bipolar disorder, at least among a highly selected group of lithium monotherapy responders. However, the majority of recent studies, which include heterogeneous samples of women with bipolar disorder, suggest that pregnancy is, indeed, a period of substantial risk for recurrence, with estimates of recurrence as high as 50% based on retrospective assessments

(15,

25 –

28) .

To our knowledge, no controlled, prospective longitudinal studies of the course of bipolar disorder during pregnancy have been reported. Studies that specifically consider the effects of diagnostic subtypes, illness history, and current treatment are required to quantify risks of bipolar disorder morbidity during pregnancy. Accordingly, we now report on a prospective study of recurrence risk among pregnant women diagnosed with bipolar disorder, comparing risk rates and time to recurrence among those who continued or discontinued mood stabilizer treatment.

Method

Subject Selection

Pregnant women (N=89) diagnosed with DSM-IV type I (N=61) or II (N=28) bipolar disorder were enrolled in this prospective, observational study of pregnancy between March 1, 1999, and Aug. 31, 2004, at the Perinatal and Reproductive Psychiatry Clinical Research Program at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. The subjects were recruited among women planning pregnancy and seeking specialized psychiatric consultation, as recommended by their obstetricians or by self-referral.

Study subjects were eligible if they 1) had a history of bipolar disorder before pregnancy, 2) were euthymic for at least 4 weeks before their last menstrual period, 3) were receiving mood stabilizer therapy or 4) discontinued pharmacotherapy within 6 months before conception or 12 weeks after conception, and 5) were enrolled before 24 weeks of gestation. Patients were excluded if they 1) were actively suicidal, 2) had discontinued all mood stabilizer therapy >6 months before conception, or 3) met DSM-IV criteria for a primary psychotic, schizoaffective, or organic mental disorder or mental retardation. All subjects provided written informed consent to participate after approval of the study protocol by the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Review Board.

The subjects were followed through the end of pregnancy and for 12 months postpartum, regardless of their decisions concerning continued use of psychotropic medication. All subjects initially received individual evaluations by the first author (A.C.V.), including an extensive clinical assessment that included the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)

(29), and comprehensive review of potential risks and benefits of continuing or stopping treatment, as detailed elsewhere

(17) . This review covered current knowledge of the potential teratogenicity of mood stabilizing, antipsychotic, sedative-hypnotic, and antidepressant drugs, their potential adverse effects on neonates, and maternal and potential fetal risks associated with discontinuing treatment.

Assessments

Initial SCID assessment confirmed a DSM-IV lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder and evaluated the presence of comorbid psychiatric illnesses. Demographic and clinical characteristics of interest were recorded at baseline, including family history, estimated age at onset of bipolar disorder, approximate number of prior episodes and hospitalizations, and occurrence of suicide attempts, as well as the type, severity, and time since the approximate onset and end of the last major affective episode and treatment history (medicines, doses, and estimated exposure times). The subjects were followed up prospectively by A.C.V. at a study visit each trimester and at 6, 12, 24, and 52 weeks postpartum to ascertain the presence of major symptoms and their clinical severity (mild, moderate, or severe) and current treatments (drugs, doses, apparent benefits, and adverse effects), noting any changes. In addition, the primary outcome variable of recurrence of a new DSM-IV illness episode was determined by an independent rater (trained and experienced research assistant) who was blind to treatment status with the SCID mood module, as reported previously in a prospective, longitudinal study of risk recurrence among pregnant women with recurrent major depressive disorder

(30) . The blinded assessment covered the interval from the last to the current study visit, with a best estimate of the gestational week of illness onset, all verified with A.C.V. when a recurrence was detected. All subjects were managed clinically by their treating psychiatrist without blinding to treatment status.

Analytic Plan

The primary outcome variables were recurrence and weeks to the start of an illness recurrence fulfilling DSM-IV criteria based on the SCID mood modules for mania, hypomania (lasting ≥1 week), major depression, or a mixed state. Neonatal and postpartum outcomes will be reported separately. Given the complexity and multiple changes in pharmacologic regimens among patients with bipolar disorder, we stratified the study group into two treatment groups based on mood stabilizer treatment status only: 1) use of at least one mood stabilizer at conception and continued at least through the first 12 weeks of pregnancy or 2) discontinuation of all mood stabilizer treatment during the period ranging from 6 months before conception to 12 weeks of gestation.

We first compared the distribution of demographic and clinical characteristics between the treatment groups to identify potential confounding factors. Associations of treatment status with risk and latency of recurrence were then assessed. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses determined median weeks to start of a first recurrence with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), with unadjusted univariate Mantel-Cox log-rank tests (χ

2 ) to compare survival times between treatment groups, and censoring at birth or miscarriage

(31) . Cox multivariate proportional hazards modeling estimated the hazard ratio and 95% CI for median time to recurrence between treatment groups, with adjustment for predictors of recurrence suggested by preliminary univariate analyses. This modeling employed forward variable selection to adjust for the effects of potential confounders and to identify potential risk factors for illness recurrence. We also used survival analysis to compare weeks to recurrence dated from the point of discontinuation of mood stabilizer treatment to compare subgroups that discontinued abruptly or rapidly (1–14 days) versus gradually (≥15 days of dose reduction). Finally, we used logistic regression modeling to evaluate risk factors for significant and independent association with recurrence.

Summary data are reported as means with standard deviations for continuous variables, survival-computed median weeks to events and hazard ratios with 95% CIs, and proportions (percentages) for categorical data, which were compared with contingency tables (χ 2 ) or Fisher’s exact test (p). Statistical tests of hypotheses were two-sided, at α=p≤0.05. Analyses used commercial statistical programs (STATA version 8.2, College Station, Tex.).

Results

Subject Characteristics

Among 89 women with bipolar disorder (69% bipolar I disorder, 31% bipolar II disorder) in the study group, 85 had a live birth, two subjects had stillbirths at term, one woman miscarried after a recurrence, and one subject dropped out of the study after a recurrence.

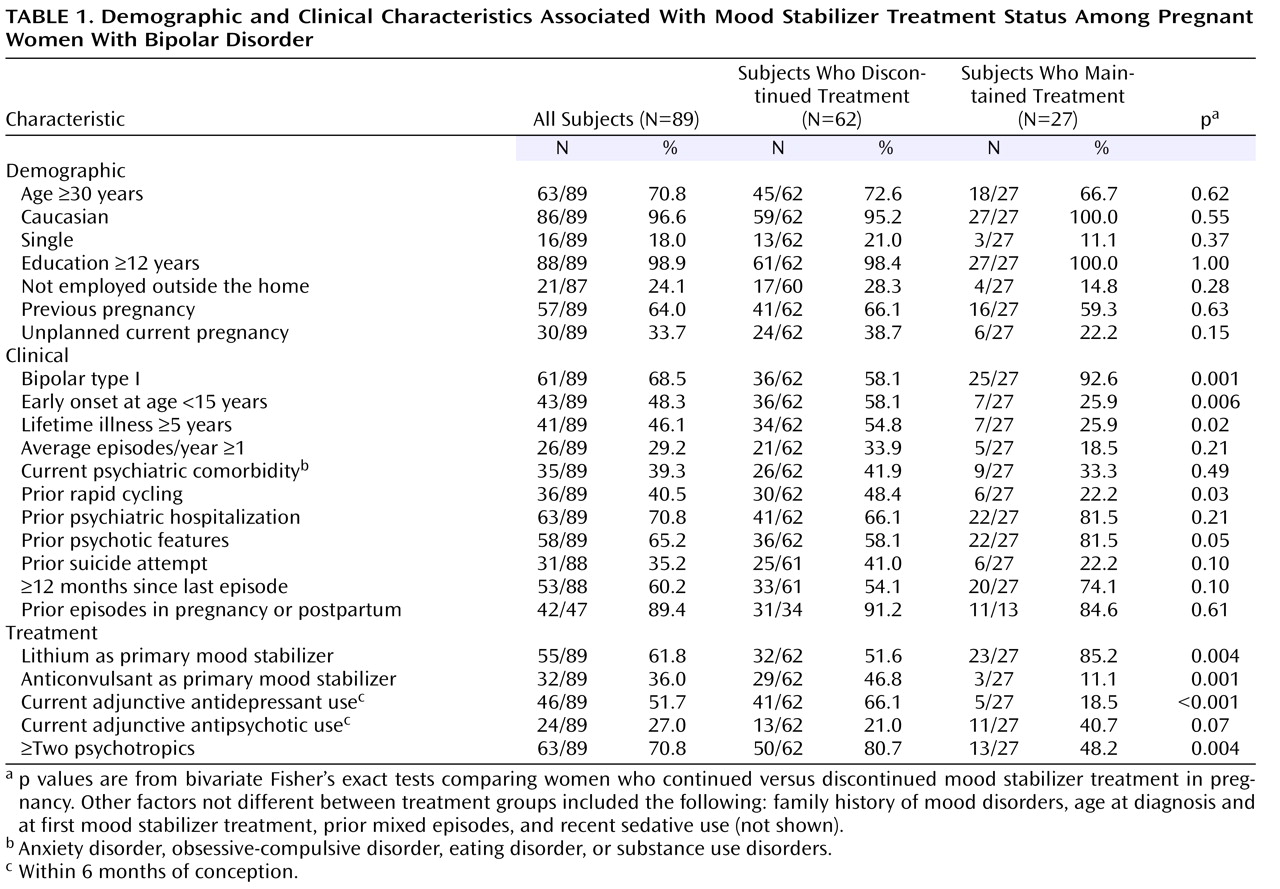

Table 1 illustrates demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics of all participants as well as those who discontinued or maintained treatment with a mood stabilizer. Overall, the mean age of the subjects was 32.7 years (SD=5.4). The majority of subjects were Caucasian (96.6%), had ≥12 years of education (98.9%), and were married (82%), employed outside the home (76.0%), and multiparous (64%). Most subjects (>70%) were taking more than one psychotropic, which included a mood stabilizer in combination with an antidepressant and/or antipsychotic (

Table 1 ). Across the study group, primary mood stabilizer type ranked as follows: lithium (55 of 89=61.8%) > anticonvulsants (32 of 89=36.0%; valproic acid, N=15; lamotrigine, N=8; carbamazepine, N=6; gabapentin, N=3) > atypical antipsychotics (two of 89=2.3%; olanzapine, N=1; and quetiapine, N=1). Over half the study group were exposed to an antidepressant (51.7%, 46 of 89; bupropion, N=15; sertraline, N=7; fluoxetine, N=8; fluvoxamine, N=1; paroxetine, N=5; venlafaxine, N=2; citalopram, N=4; selegiline, N=1; tricyclic, N=1; tranylcypromine, N=2) in addition to a mood stabilizer. Among subjects who continued taking a mood stabilizer, 18.5% used adjunctive antidepressants versus 66.1% (41 of 62) of those who discontinued mood stabilizer. In addition, 27% (24 of 89) of the cohort was exposed to an antipsychotic (olanzapine, N=6; quetiapine, N=2; perphenazine, N=4; risperidone, N=4; thiothixine, N=2; haloperidol, N=3; or ziprasidone, N=3), and the proportion of adjunctive antipsychotic use was higher among subjects who maintained versus discontinued a mood stabilizer (

Table 1 ).

At study entry, the two treatment groups did not differ significantly with respect to demographic features (i.e., age, race, marital status, years of education, employment, and previous pregnancy) and several characteristics, including unplanned pregnancy, average episodes/year, current comorbidity, prior hospitalizations, prior suicide attempts, time since last episode, and prior perinatal and postpartum episodes (

Table 1 ), as well as family history of mood disorders, age at diagnosis and at first mood stabilizer treatment, prior mixed episodes, and recent sedative use (not shown). However, the two groups did differ along several important measures of illness severity (

Table 1 ). Those who

continued maintenance mood stabilizers during pregnancy were more likely to 1) have bipolar I disorder, 2) be maintained with lithium as the primary mood stabilizer, 3) have a history of psychotic features, and 4) be treated with adjunctive antipsychotics. The women who

discontinued mood stabilizer treatment were more likely to 1) have a bipolar II disorder diagnosis, 2) have discontinued an anticonvulsant, 3) have experienced onset of bipolar disorder at a younger age and with a depressive first episode, 4) be treated with ≥two psychotropics, 5) be ill more total years, 6) experience a history of rapid cycling (≥4 episodes in any year), and 7) be treated with an antidepressant (

Table 1 ).

Risk and Timing of Recurrences During Pregnancy

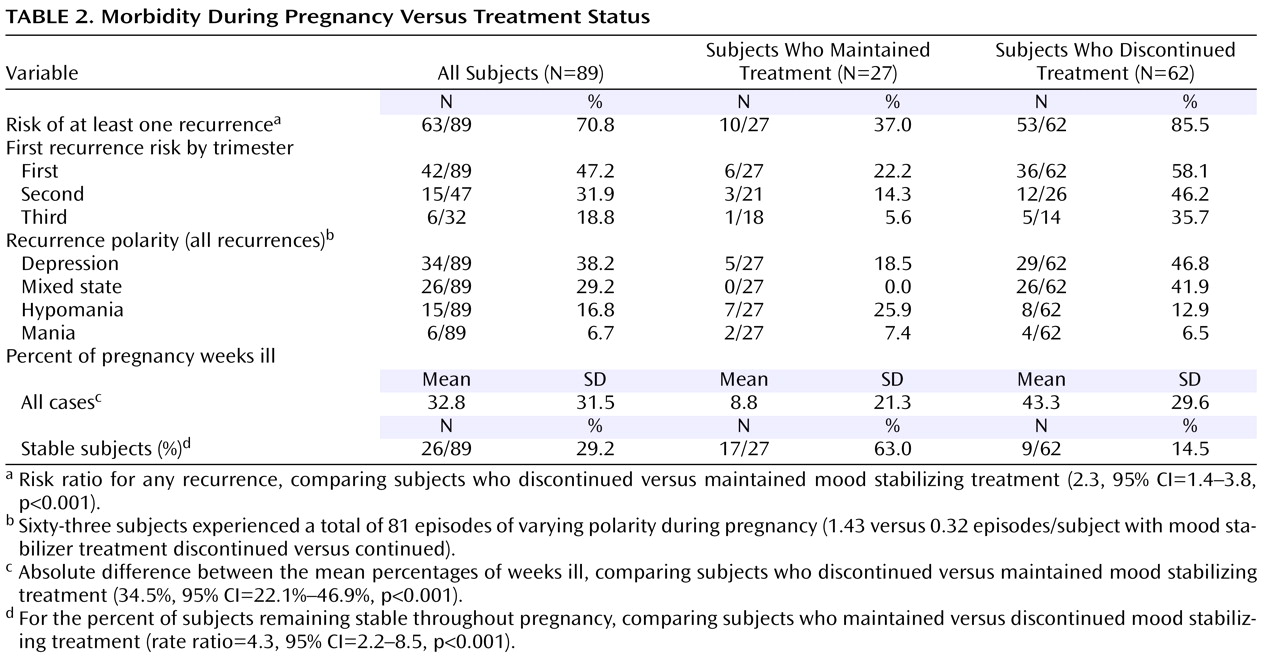

During pregnancy, a total of 70.8% (63 of 89) of the subjects experienced at least one episode of illness meeting DSM-IV SCID criteria. Overall, there were a total of 81 episodes, including shifts in polarity without intervening recovery, yielding an average of 1.3 episodes per affected subject (81 in 63) during the study period (

Table 2 ). Recurrence risk was 2.3 times greater after discontinuation of mood stabilizer treatment (53 of 62, 85.5%) than with continued treatment (10 of 27, 37.0%;

Table 2 ). In addition, the proportion of time spent ill (i.e., with a mood episode) during pregnancy was nearly a third (33%) of the pregnancy across the entire cohort. The subjects who discontinued the mood stabilizer spent over 40% of pregnancy in an illness episode, versus only 8.8% of pregnancy among subjects who maintained the mood stabilizer (

Table 2 ).

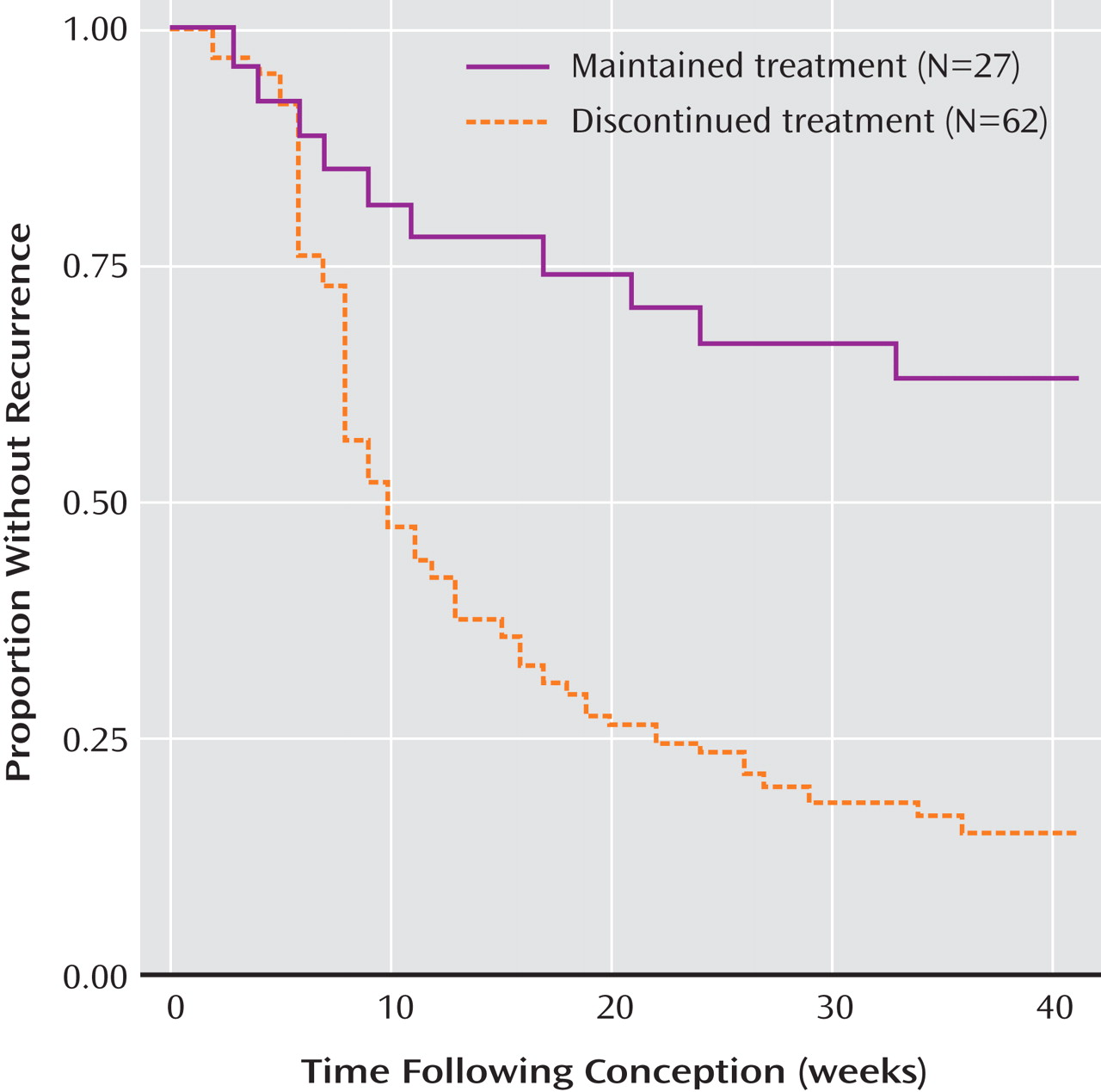

Based on Kaplan-Meier survival analyses, the median time to first recurrence was 9.0 (95% CI=8.0–13.0) weeks after discontinuing treatment and >40 weeks (95% CI indeterminate) with continued treatment (

Figure 1 ). With respect to the timing of recurrences, the majority of new episodes emerged early in pregnancy: 47.2% risk in the first trimester, 31.9% in the second, and 18.8% in the third (

Table 2 ).

Rate of Discontinuation of Mood Stabilizer

Women who discontinued abruptly or rapidly (1–14 days; N=35) experienced a 50% risk of recurrence within 2.0 (95% CI=1.0–6.0) weeks, and those who discontinued gradually (≥15 days, N=27) required 22.0 (95% CI=16.0–38.0) weeks to reach the same level of recurrence risk (χ 2 =25.9, df=1, p<0.0001; not shown). It is noteworthy, and perhaps not surprising, that unplanned pregnancy covaried with greater likelihood of rapid discontinuation of mood stabilizer treatment (23 of 24, 95.8%, versus 12 of 59, 20.3%, in planned pregnancies; p<0.0001, Fisher’s exact test).

Polarity of Recurrences

The distribution of polarities across all first recurrences ranked as follows: major depression (41.3%, 26 of 63) > mixed states (38.1%, 24 of 63) > hypomania (11.1%, seven of 63) > mania (9.5%, six of 63), indicating a 3.8-fold excess of depressive or dysphoric (mixed) versus manic or hypomanic recurrences (79.4%, 50 of 63, versus 20.6%, 13 of 63). The excess of depressive-dysphoric versus manic-hypomanic episodes was even greater after discontinuation of mood stabilizer treatment (55 of 62 recurrences, 88.7%, versus 12 of 62, 19.3%, or 4.6-fold) compared to continued treatment (five of 27, 18.5%, versus nine of 27, 33.3%, or only a 1.8-fold difference). The excess of new depressive-dysphoric versus manic-hypomanic illness was found among both bipolar I disorder cases (25 of 61, 40.9%, versus 12 of 61, 19.6%, or 2.1-fold) and bipolar II disorder subjects who demonstrated a 24-fold excess of depression over hypomania (25 of 28, 89.3%, versus one of 28, 3.7%).

Predictors of Recurrence During Pregnancy-Unadjusted Analysis

We examined whether certain demographic or clinical variables, other than discontinuation of mood stabilizer, were associated with recurrence during pregnancy. No statistically significant association was noted between recurrence risk and race, educational status, or marital status. However, several other clinical factors, including illness history, pregnancy, and treatment-related factors were associated with illness recurrence during pregnancy. Significant illness-history-related predictors included the following in rank order by risk ratio: 1) ≥5 years of illness (risk ratio=1.7, p<0.001), 2) younger age at onset (risk ratio=1.6, p<0.001), 3) bipolar II disorder diagnosis (risk ratio=1.5, p<0.002), 4) history of rapid cycling (risk ratio=1.5, p<0.002), 5) shorter clinical stability since the last episode before conception (risk ratio=1.5, p<0.004), 6) one or more prior episodes per year (risk ratio=1.5, p=0.004), 7) previous mixed-state episodes (risk ratio=1.5, p=0.004), 8) prior suicide attempts (risk ratio=1.4, p=0.01), and 9) current psychiatric comorbidity (risk ratio=1.4, p=0.02). Pregnancy-related risk factors associated with recurrence only included 10) unplanned index pregnancy (risk ratio=1.5, p=0.006), but not previous live birth or prior history of a mood episode during pregnancy or the postpartum period. Treatment-related risk factors, besides discontinuation of mood stabilizer, included 11) polytherapy with two or more psychotropic agents (risk ratio=2.3, p<0.001), 12) use of antidepressants (risk ratio=2.0, p<0.001), 13) primary mood stabilizer other than lithium (risk ratio=1.6, p<0.001), 14) previous switch from depression to mania-hypomania during treatment with an antidepressant (risk ratio=1.5, p<0.009), and 15) abrupt discontinuation of mood stabilizer (risk ratio=1.4, p=0.008). Factors not associated with recurrence included race, age, education, marital status, employment, previous pregnancy, prior illness in pregnancy or during the postpartum period, first episode depressive, any family history of mood disorder, and current use of more than one mood stabilizer, among others (not shown).

Multivariate Modeling of Risk-Factors-Adjusted Analysis

The preceding factors preliminarily associated with recurrence of bipolar disorder illness during pregnancy were subjected to multivariate analysis with Cox proportional hazards modeling to test for factors remaining independently associated with recurrence latency (not shown). Without adjustment for covariates, time to recurrence was much shorter after treatment discontinuation (hazard ratio=3.80, 95% CI=1.90–7.60) and remained so (hazard ratio=2.50, 95% CI=1.20–5.20) even after adjustment for indices of illness severity (lifetime years ill and number of prior episodes), bipolar disorder diagnostic subtype (I or II), and antidepressant use. Furthermore, in this multivariate model, indices of illness severity and bipolar type were no longer associated with increased hazard, but antidepressant use remained a robust predictor of recurrence risk along with treatment discontinuation (hazard ratio=2.2, 95% CI=1.2–4.2, p=0.02).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective and systematic assessment of risk and predictors of recurrence among pregnant women with bipolar disorder. The main findings of this study are a twofold greater recurrence risk and the more than fourfold shorter latency to new illness among women who discontinued maintenance mood stabilizing treatment proximate to conception, compared to those who continued treatment (

Table 2,

Figure 1 ). Moreover, recurrence risk was even greater and earlier after rapid discontinuation of mood stabilizing treatment. These findings replicate and extend our previously published retrospective findings of high recurrence rates during pregnancy among women with bipolar disorder who discontinued lithium, especially abruptly

(15,

32 –

34) . In the present study, recurrence risk in pregnancy (85%) was approximately 33% higher compared to our previous estimate of 52%, perhaps reflecting the current study’s prospective design, with greater sensitivity to detecting new illness episodes, and a more heterogenous study group that included women who discontinued mood stabilizers other than lithium.

We also observed a striking excess of depressive or dysphoric mixed illness, especially early in pregnancy, in the present cohort (74.1% of all episodes), whereas mania and hypomania were relatively infrequent. Some of this excess of depression may be accounted for by including bipolar II disorder cases (31.5% of subjects), but a similar excess of depression-dysphoria over mania or hypomania was found among bipolar I disorder cases (40.9% versus 19.6%). It may be that pregnancy predisposes vulnerable patients to depressive-dysphoric recurrences, as observed nearly 150 years ago by Louis-Victor Marcé of Paris

(35,

36) . Modern reports also indicate an excess of depressive morbidity during pregnancy among women with bipolar disorder

(15,

24,

26,

27), but also among treated, nonpregnant samples of bipolar disorder patients

(4 –

6) .

Predictors of illness recurrence during pregnancy, besides the most robust risk factor of discontinuing mood stabilizer treatment, included characteristics associated with illness severity. Such factors were younger onset, more years of illness and more recurrences, a history of rapid cycling, suicide attempts, presence of comorbid disorders, and antidepressant use. Cox multivariate analyses indicated that antidepressant use and treatment discontinuation each operated independently as risk factors even after adjustment for other indices of illness severity.

Several of these risk factors for mainly depressive recurrences during pregnancy also are associated with general risk of depressive morbidity in bipolar disorder patients, including a bipolar II disorder diagnosis and use of an antidepressant during pregnancy

(4,

6) . Use of antidepressants during pregnancy, especially after discontinuing mood stabilizers, may have exerted mood-destabilizing effects

(36 –

39) . Alternatively, antidepressant use during pregnancy may reflect the presence of bipolar II disorder patients, who are often treated with antidepressants, or may simply be an indicator for more severe illness

(40 –

42) . Moreover, their use may also be further encouraged by current impressions that antidepressants might have less risk of teratogenic or other adverse developmental effects than some mood stabilizers

(17,

18,

43,

44) .

It is also noteworthy that nearly 70% of the present study subjects and their physicians elected to discontinue mood stabilizing treatment at the start of pregnancy, particularly among women with severe illness histories. Not surprisingly, patients with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder with a history of previous psychotic features or current antipsychotic treatment were more likely to continue maintenance medications (

Table 1 ). However, many other subjects with similar morbid histories, including early onset and relatively high number of prior illness recurrences, chose to discontinue mood stabilizer. Similarly, we have found that among women with recurrent major depressive disorder, decisions to maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment during pregnancy appeared to be largely independent of severity of past illness or clinical recommendations

(30) . Other observations suggest that decisions about continuing or discontinuing pharmacological treatment for mood disorders during pregnancy often are ill-informed, based primarily on fear of psychotropic use during pregnancy

(12 –

15) .

This study has notable limitations. Although prospective and systematic, it is a naturalistic, observational study. Treatment was determined clinically, without experimental control or random assignment, and in some cases was complex and variable over time. Moreover, the subjects in each treatment subgroup were limited in number and, in the absence of random assignment, not necessarily matched on all potentially relevant clinical variables (

Table 1 ). Nevertheless, there was little evidence of differences in illness history or major demographic variables between treatment groups (

Table 1 ). We also attempted to control for potentially relevant differences with Cox multivariate modeling of survival functions to test for the independent contribution of treatment discontinuation as well as other relevant risk factors identified in preliminary bivariate analyses.

An additional limitation of the study is that the patients included may not be representative of broader samples of bipolar disorder patients, including less well-educated women, members of minority groups, and others who may be less likely to seek highly specialized care during pregnancy. Nevertheless, it is sobering to find that, even among women who seemed highly motivated to seek out expert care, the morbid risks of bipolar disorder during pregnancy and especially with discontinued treatment were very high.

This study adds to evidence that discontinuation of ongoing maintenance mood stabilizing treatment in women with bipolar disorder carries a very high risk of illness recurrence during pregnancy. Pregnancy appears not to have a protective effect against new or worsening illness in bipolar disorder patients and may particularly increase the risk of new depressive morbidity, with uncertain effects on fetal development

(45) . Although a number of clinical risk factors were identified that may have clinical predictive value in identifying women at particularly high recurrence risk, mood stabilizer discontinuation itself appeared to be a very important predictor of recurrence. As we have proposed previously, any subtle positive or negative effects pregnancy may have on the illness course is likely dwarfed by the more dominant stressor of abrupt treatment discontinuation

(15,

17,

32 –

34) .

In conclusion, the present findings challenge the evidently common practice of abruptly stopping maintenance treatment for psychiatric disorders during pregnancy. Of importance, they underscore the significant benefits of continuing prophylactic mood stabilizing treatment during pregnancy with respect to overall reduction in recurrence risk and overall maternal morbidity (i.e., time spent ill during pregnancy). A major clinical implication of these findings is that for women with severe and frequent recurrences of bipolar disorder, maintenance treatment with a mood stabilizer during pregnancy may be the most prudent strategy, much as maintenance treatment is recommended for pregnant women with other serious and chronic medical conditions, such as epilepsy

(46,

47) . In short, given the high risk of maternal morbidity associated with discontinuation of mood stabilizing treatment and its uncertain impact on fetal development, we recommend a more balanced consideration of the entire spectrum of risks and benefits involved in the clinical management of pregnant women with bipolar disorder.