Descriptive Information

Of the total sample of 1,420 children, 473 (31.5% weighted) were arrested between ages 16 and 21. As expected, more males (42.8%) than females (19.6%) were arrested (odds ratio=3.1, 95% confidence interval [CI]=2.1–4.6). Among those arrested, slightly more than half (N=241, 55.1%) were arrested for minor offenses, 26.7% (N=145) were arrested for moderate offenses, and about one in five (N=87, 18.3%) were arrested for severe/violent offenses. The total number of offenses per individual differed significantly across the arrest severity groups (z=10.8, p<0.001), with the mean rates ranging from 2.3 (SD=1.9) for the minor offense group to 10.5 (SD=15.3) for the moderate offense group and 15.1 (SD=18.9) for the severe/violent offense group. As expected, offense category was strongly predicted by male sex (minor offenses: odds ratio=2.5, 95% CI=1.8–3.3; moderate offenses: odds ratio=2.4, 95% CI=1.6–3.6; severe/violent offenses: odds ratio=14.0, 95% CI=6.4–30.3). Given the small number of females arrested for a severe/violent offense (N=13), these participants are grouped with the moderate female offenders in all further analyses. No between-groups differences in ethnicity were observed between whites and American Indians (minor offenses: odds ratio=0.8, 95% CI=0.5–1.1; moderate offenses: odds ratio=0.7, 95% CI=0.4–1.1; severe/violent offenses: odds ratio=0.8, 95% CI=0.4–1.3).

Childhood Psychiatric Disorders and Young Adulthood Arrest Status

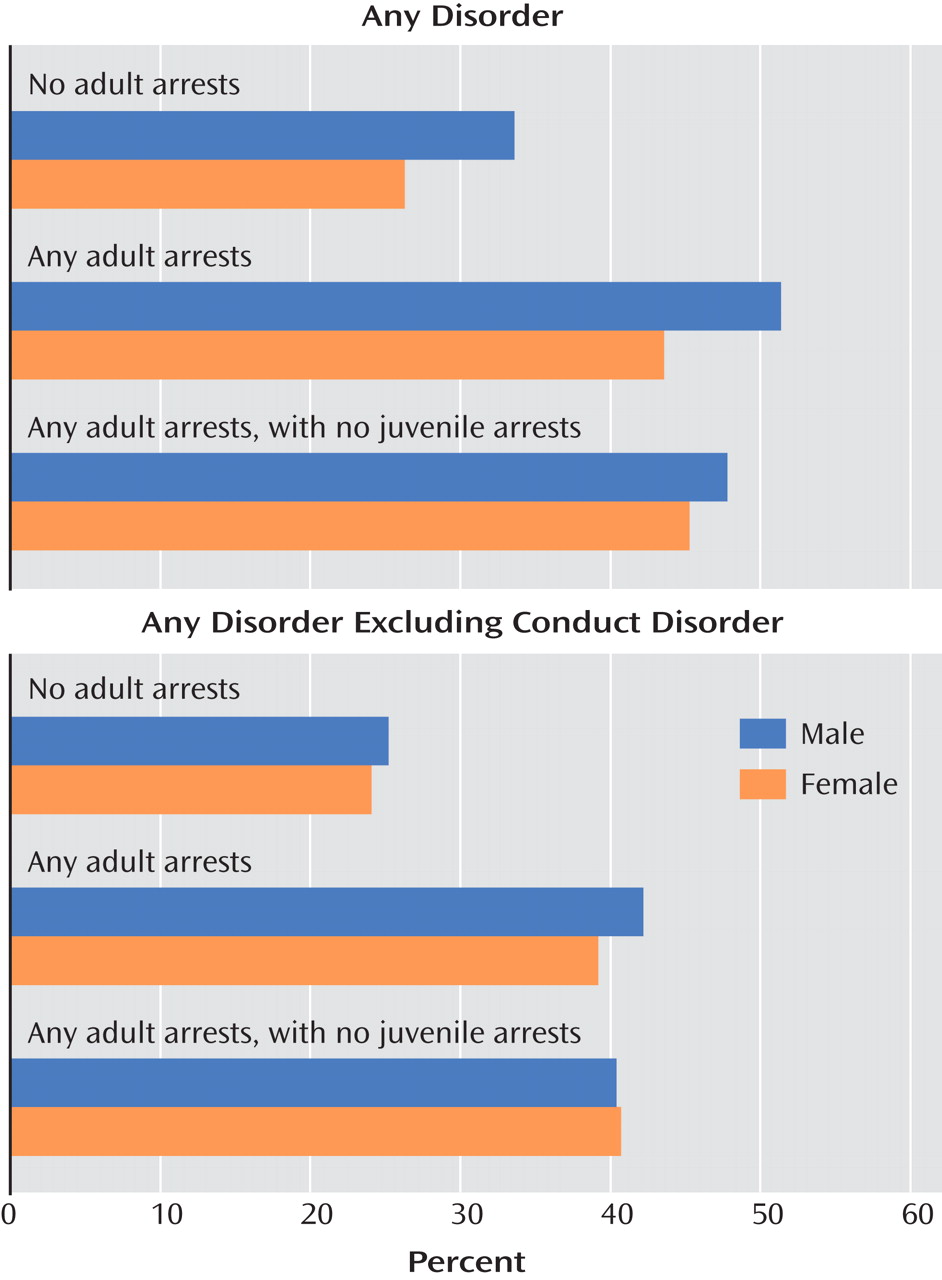

Figure 1 compares the prevalences of overall childhood diagnoses among those with no arrests, those with arrests in young adulthood (ages 16–21) only, and those with arrests as juveniles (through age 15) and in young adulthood. Cumulative rates of DSM-IV disorders for children (through age 16) with no young adult offenses were 33.6% (SE=3.7) for boys and 26.3% (SE=3.0) for girls, compared with rates of 51.4% (SE=4.6) for male offenders and 43.6% (SE=6.9) for female offenders (male offenders: odds ratio=2.2, 95% CI=1.1–4.1; female offenders: odds ratio=2.1, 95% CI=1.3–3.4). This discrepancy remained even in analyses controlling for juvenile history of criminality (male offenders: 47.8% versus 31.6%, odds ratio=2.0, 95% CI=1.1–3.4; female offenders: 45.3% versus 24.5%, odds ratio=2.6, 95% CI=1.3–5.2). The likelihood of an adult arrest was not higher for youths who had a juvenile criminal history in addition to a childhood psychiatric disorder than for those with a childhood psychiatric disorder and no juvenile criminal history.

Given the overlap between conduct problems and criminal behavior, the analyses were repeated with conduct disorder diagnoses excluded. As expected, the prevalence of childhood psychiatric disorders decreased across all arrest status groups, and more so for males than for females. However, childhood diagnoses other than conduct disorder remained significantly higher for participants who had been arrested in young adulthood, irrespective of whether they had also been arrested as juveniles (male offenders: 40.4% versus 23.4%, odds ratio=2.2, 95% CI=1.2–4.1; female offenders: 40.7% versus 22.4%, odds ratio=2.4, 95% CI=1.1–5.2).

We computed the population-attributable risk

(31) of crime in this sample—that is, an estimate of the proportion of adult crime in this study that is attributable to child psychiatric disorder exposure: 19.5% of crime among females and 28.7% of crime among males in this study is attributable to juvenile mental disorders. Adjusted for juvenile justice status and conduct disorder, the population-attributable risk estimates for females and males are 20.6% and 15.3%, respectively.

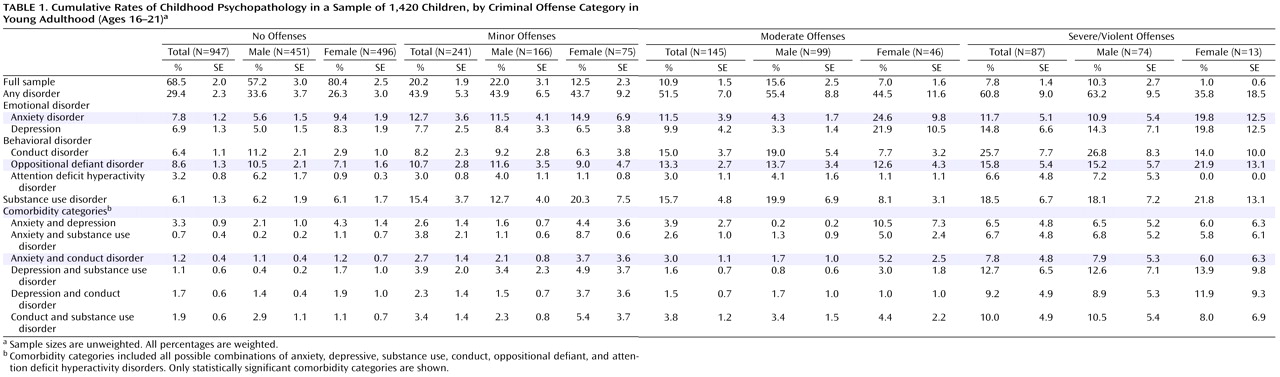

Table 1 presents the cumulative prevalence rates of single diagnoses and common comorbid diagnostic categories for each arrest group. Cumulative comorbid diagnostic groups were derived by determining whether children met diagnostic criteria for more than one disorder during their time in the study (not necessarily at the same time point).

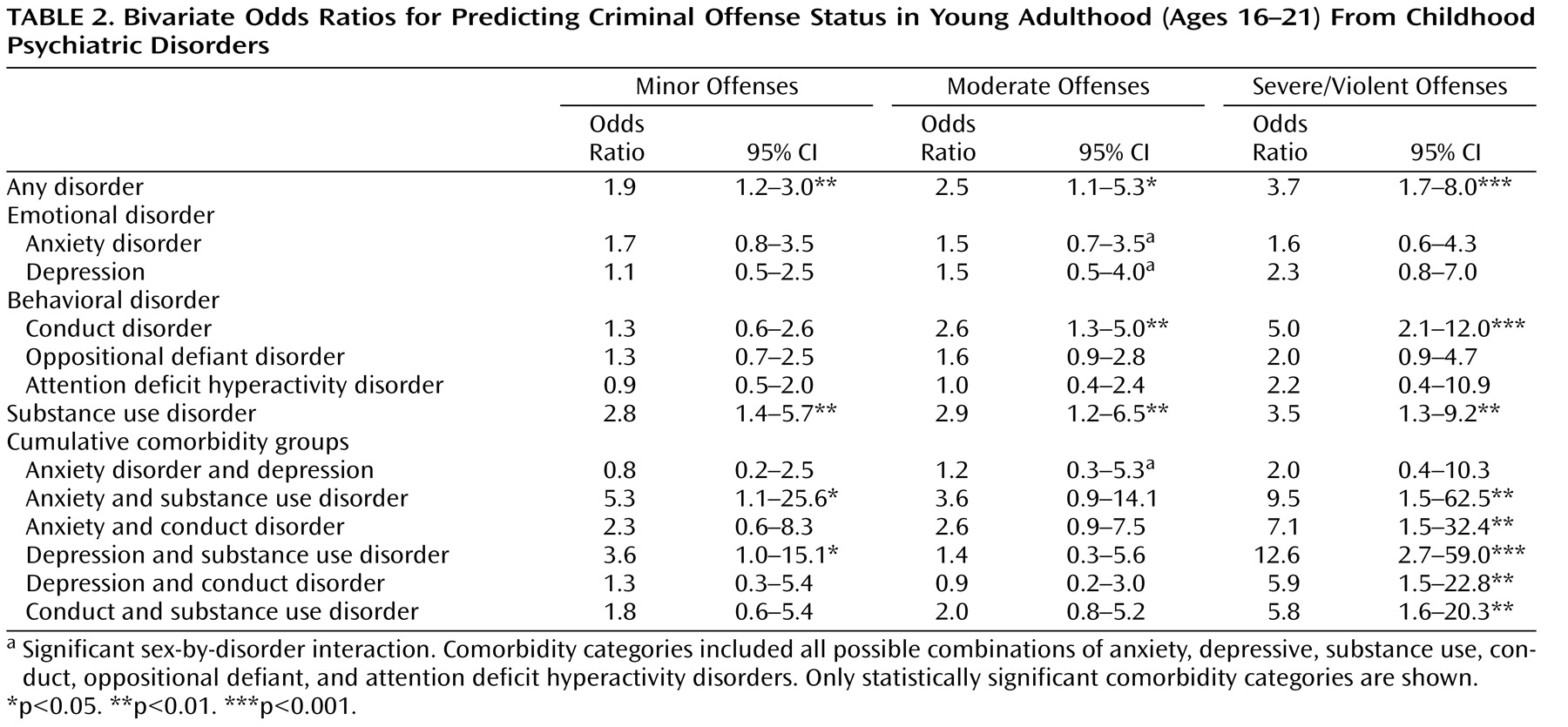

Table 2 presents the odds ratios for the associations between childhood psychiatric disorders and criminal offense status in young adulthood, comparing those who had not been arrested with those who had been arrested for minor, moderate, and severe/violent offenses in separate analyses.

Only psychiatric histories involving a substance use disorder, either alone or comorbid with another psychiatric disorder, predicted subsequent arrest for minor offenses in young adulthood. While arrests for both moderate and severe/violent offenses were predicted by conduct and substance use disorder, arrest for severe/violent offenses was also predicted by comorbidity groupings involving conduct disorder, substance disorder, and emotional disorders.

Sex-by-diagnosis interactions were tested for each disorder, and few were statistically significant. All significant sex differences were observed for associations between emotional disorders and moderate offenses. For male participants, emotional disorders did not predict arrest for moderate offenses (anxiety disorders: odds ratio=0.7, 95% CI=0.3–2.0; depressive disorders: odds ratio=0.6, 95% CI=0.2–1.8), nor did they predict lower offense status (comorbid anxiety and depressive disorder: odds ratio=0.1, 95% CI=0.1–0.8). For female participants, in contrast, comorbid anxiety and depression did not predict offense status (odds ratio=2.6, 95% CI=0.5–13.9), but depressive disorders showed a nonsignificant trend toward predicting offense status (odds ratio=3.1, 95% CI=0.9–11.4, p=0.08) and anxiety disorders significantly predicted arrest for moderate offenses (odds ratio=3.1, 95% CI=1.0–9.6).

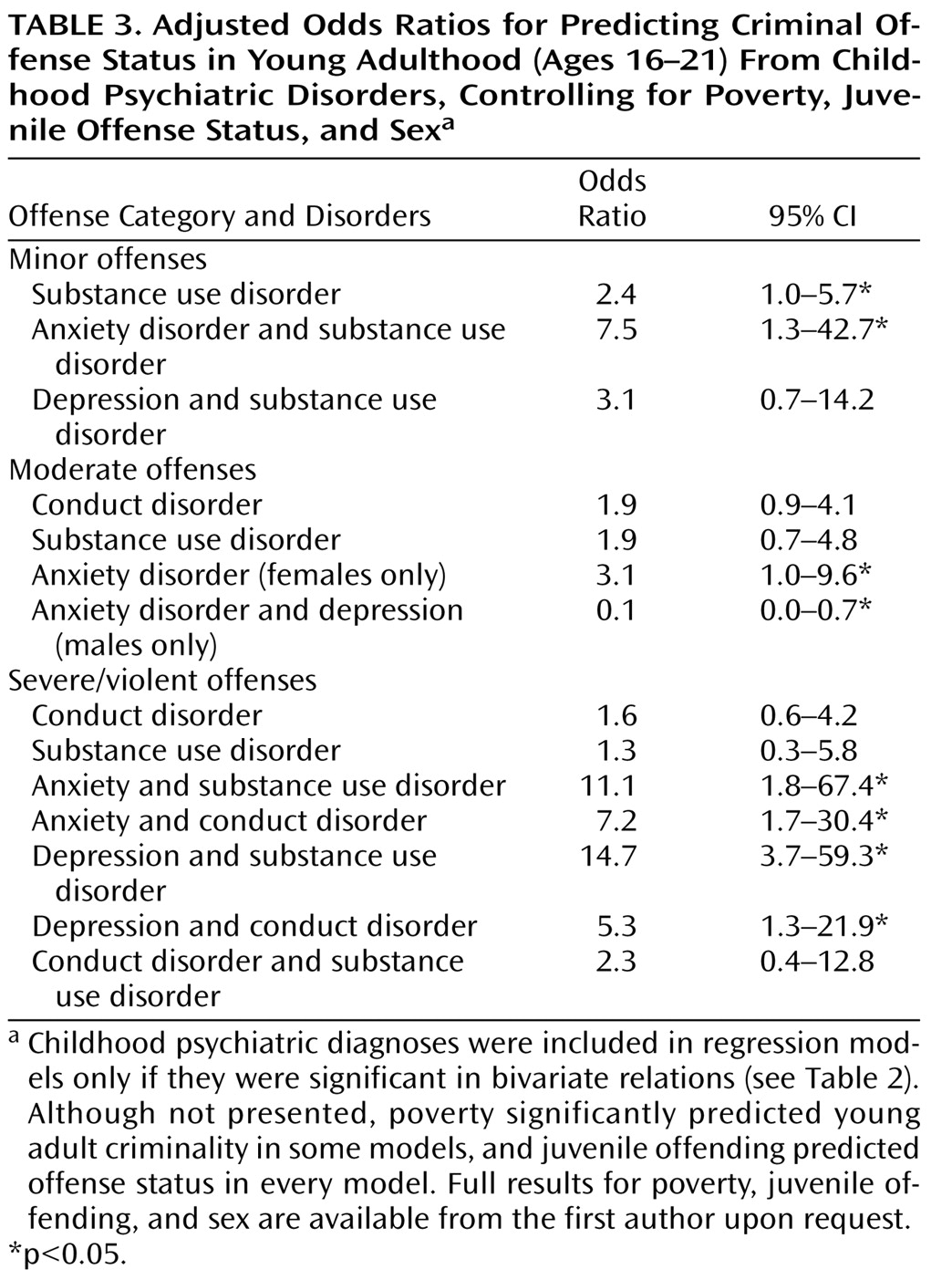

Finally, we examined the association between each childhood psychiatric diagnosis and young adult criminality, controlling for two childhood variables that have been shown to have an effect on offense status—poverty and juvenile arrest status. Sex was also treated as a covariate because of differences in rates of disorders and offense groups between males and females. Childhood psychiatric disorders that were significantly related to young adult offense status in the bivariate analyses (see

Table 2 ) were retested, including the control variables. In the few cases in which sex-by-disorder interactions were observed, models were tested separately by sex.

As

Table 3 shows, psychiatric predictors differed by offense group and by sex. Two of three bivariate predictors continued to predict minor offense status, and both involved substance use disorders. Moderate offense status was predicted only by emotional disorders, but the effect of these disorders was sex specific: in females, childhood anxiety was a risk factor, and in males, childhood anxiety and depression were protective factors. Four of seven possible bivariate predictor combinations predicted severe/violent offenses, and each involved a comorbid group. While conduct and substance use disorders were involved in each significant predictor of severe/violent offenses, neither conduct nor substance use disorders alone was a predictor.