Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast in late August of 2005 and has since become the most costly natural disaster in U.S. history

(1,

2) . Levee breaches in New Orleans and hurricane aftermath in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi directly affected more than 1.5 million people, of whom over one-third were displaced. Relief efforts in disasters usually focus on immediate needs such as shelter, food, first aid, and treating acute medical conditions

(3,

4), and the response to Katrina generally followed this approach

(5) .

Accounts of the disaster and the affected populations suggest that the mentally ill might have been hit especially hard. Prior to the disaster, people residing in Katrina’s path were already among the sickest and poorest in the nation

(6) . Widespread experience of trauma may have exacerbated preexisting mental disorders and produced new-onset disorders

(7) . Delivery systems were decimated, creating financial and structural barriers to care that may have been especially difficult for the mentally ill to overcome

(8) .

Under such circumstances, Katrina survivors with mental disorders may have experienced two types of unmet treatment needs. Those with preexisting mental disorders who had been receiving ongoing treatment before Katrina may have experienced disruptions in care because of new competing demands or the loss of providers, facilities, pharmacies, records, or means of payment

(9) ; whether emergency services helped compensate for such disruptions (e.g., through rapid clinical assessment or maintenance of prehurricane treatments, including pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy) remains unclear. Unmet treatment needs may also have occurred among Katrina survivors without prior mental illness who experienced new disorders after the hurricane. In addition to facing the barriers already mentioned, those with new cases of mental illness may have failed to initiate treatment because of attitudinal factors such as low perception of need or stigma

(10) .

The present study examined both the disruption of existing treatments and the failure to initiate treatment in a study cohort of Katrina survivors. We assessed self-reported barriers to obtaining care for individuals who experienced treatment disruption or failed to initiate treatment and identified the modes and sectors of treatment used by individuals receiving post-Katrina mental health services. Finally, we identified correlates of both disruption of existing treatment and failure to initiate new treatment as a means of informing the design and target of future interventions for disaster survivors with mental disorders.

Discussion

These results should be interpreted with the following limitations in mind. First, the study excluded people that could not be reached by telephone; as a result, the most disadvantaged and possibly most severely ill are underrepresented in the survey. Systematic nonresponse (i.e., higher survey refusal rates for individuals with mental disorders than for individuals without mental disorders) or systematic nonreporting (i.e., recall failure, conscious nonreporting, or error in diagnostic evaluation) are also possible. Prior studies suggest that nonresponse and nonreporting lead to underreporting of traumatic events as well as underreporting of mental disorders resulting from traumatic experiences, therefore resulting in an underestimation of unmet treatment needs

(19) .

Second, psychopathology was not assessed using structured diagnostic instruments but by chronic condition checklists and a screening scale. For the K-6 screening scale, diagnostic concordance with clinical interviews has been consistently good, both in our small reappraisal of Katrina survivors and in earlier methodological studies

(11,

20) . However, individual-level imprecision regarding diagnoses may have increased because of the use of such measures.

Third, corroborating data on treatments were lacking, so it is possible that the self-reported information on mental health service use is somewhat biased. Some investigators have found that self-reports of treatments may overestimate mental health service use in administrative records, especially regarding the frequency of visits

(21) . Finally, the study’s cross-sectional design prevents us from concluding that the observed correlates and reasons are causally related to mental health service use.

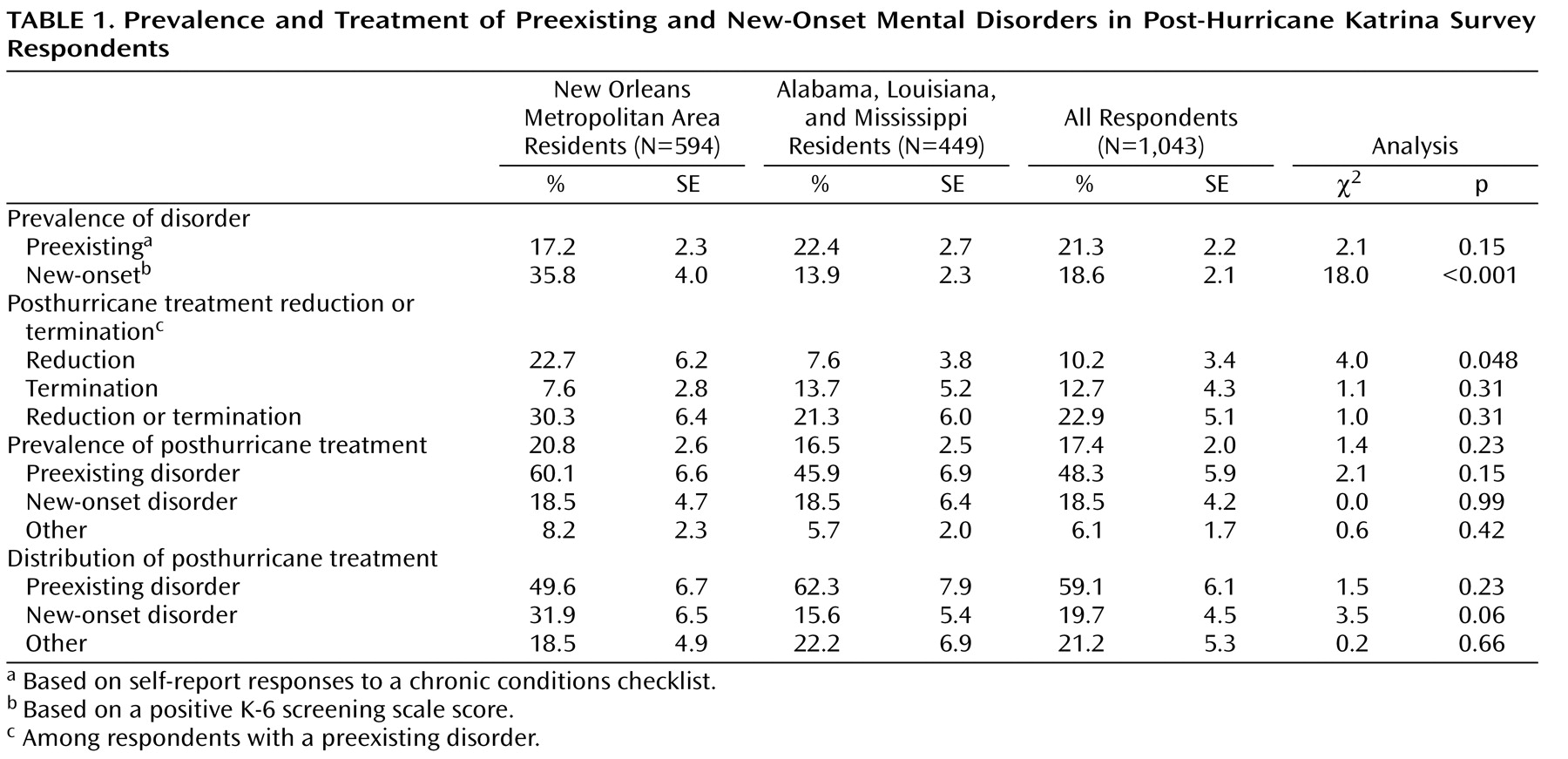

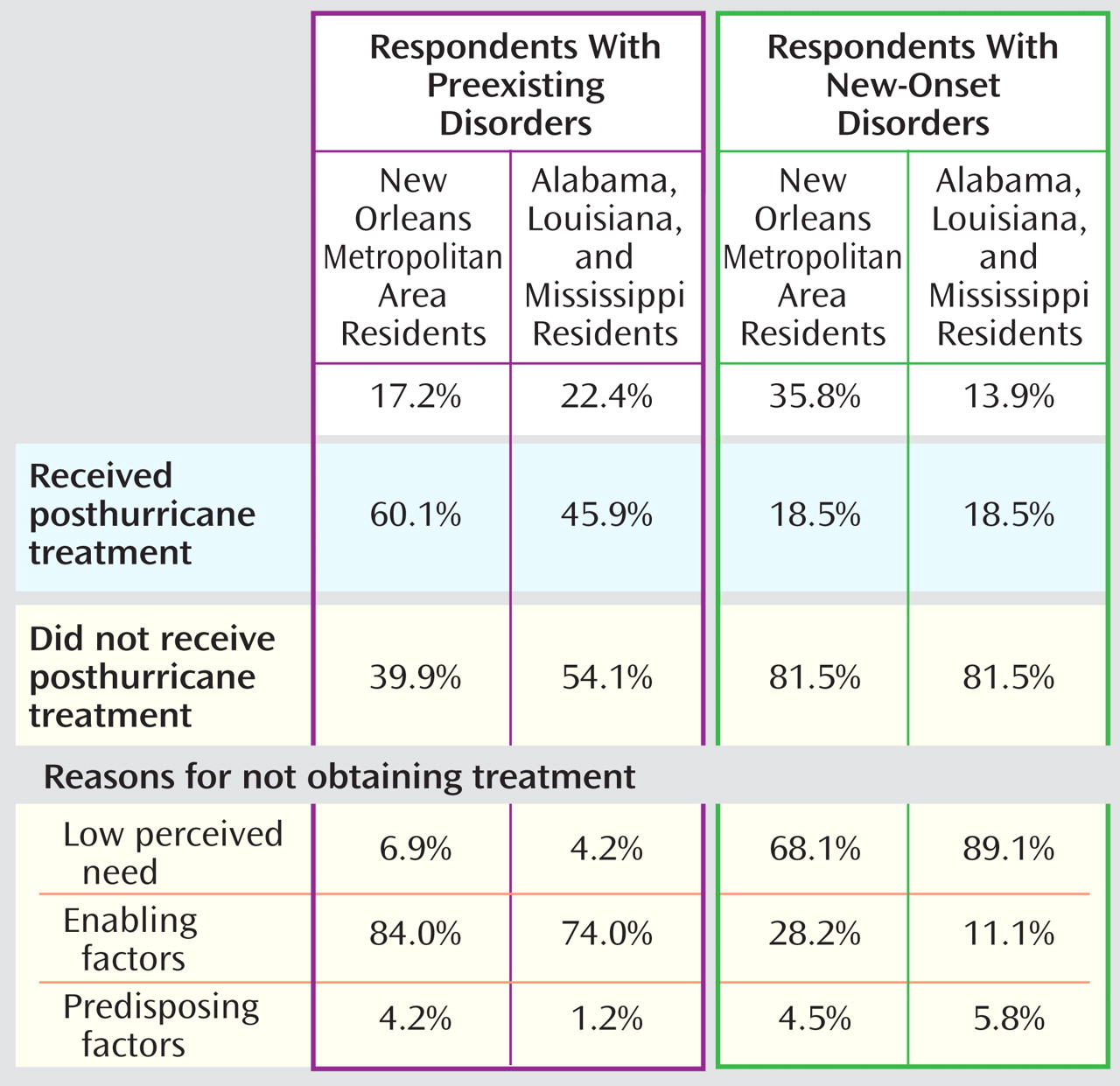

With these limitations in mind, the results of this study reveal that two forms of unmet treatment needs were common among Katrina survivors with mental disorders: disruption of existing treatments among individuals with prior needs and failure to initiate treatment among individuals with new needs. Over one-fifth (21.3%) of respondents reported having an active mental disorder in the 12 months before the hurricane, a somewhat higher estimate than previously reported in the two Census Divisions subsequently affected by Katrina

(7,

22) . Among respondents with preexisting disorders, over one-fifth experienced disruptions in care after the hurricane, including roughly equal proportions of respondents receiving fewer mental health services and respondents receiving no mental health services post-Katrina. Among respondents not reporting mental disorders in the year before the hurricane, 18.6% developed new-onset disorders; this percentage was significantly higher for respondents residing in metropolitan New Orleans than for those residing in other affected areas. Only one-fifth of respondents with new-onset disorders received any treatment during the posthurricane period. The limited data available on mental health service use after disasters corroborate our findings. Among evacuees living in Louisiana FEMA shelters, parents reported difficulties maintaining and initiating mental health treatments for both themselves and their children

(23) . Even after disasters not marked by large-scale displacement or destruction, many with mental health needs experience difficulty accessing or continuing care

(24 –

28) .

Our findings of frequent disruption in existing treatments and widespread failure to initiate new treatment may not be surprising, given the already high levels of undertreatment in the U.S.

(29) and the fact that Katrina affected individuals (mostly racial or ethnic minorities) who were among the poorest in the nation before the hurricane. However, these results may not be unique to Katrina survivors and could possibly generalize to those populations that would be adversely impacted by future catastrophes. Unfortunately, both individuals with lesser financial means and racial and ethnic minorities have been shown to be at higher risk of psychological harm from disasters, even though they possess fewer resources and means of support to cope with the hardships resulting from such catastrophes

(30 –

32) .

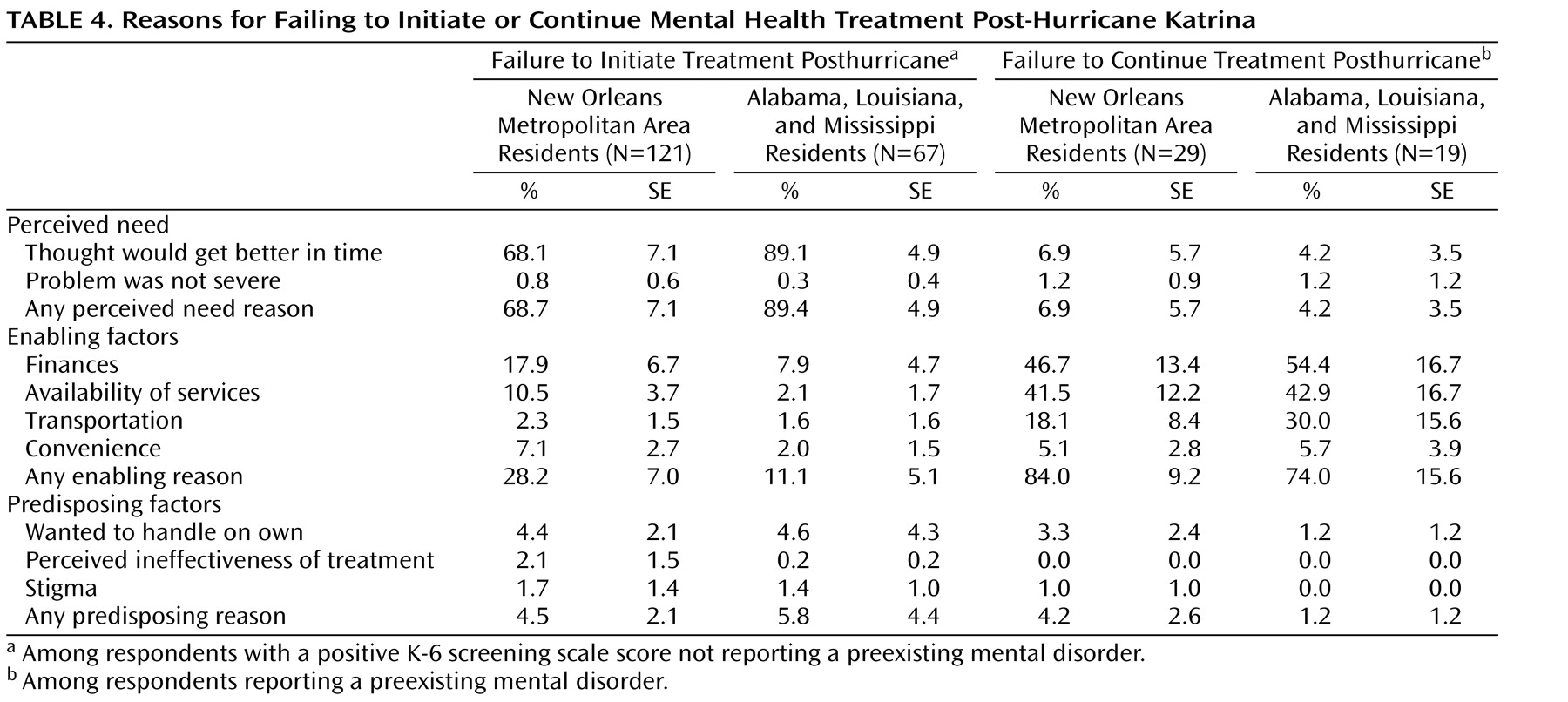

Furthermore, following Hurricane Katrina there was widespread loss of mental health care facilities, treatments, and personnel, as well as the loss of employment and the financial resources and insurance to pay for care

(8,

33,

34) . These losses were greatest in New Orleans, which perhaps explains why reductions in existing treatment were more common here than in other affected areas. Such losses of infrastructure, personnel, and financial means to pay for treatment are reflected in our findings, as the vast majority of respondents with preexisting disorders indicated “lack of enabling factors” as the reason for disruption of treatment. Mental disorders are also often associated with low perceived need for treatment, high levels of stigma, and even avoidance for fear of reexperiencing painful memories

(10,

35) . These attitudinal barriers to treatment appear to explain why many respondents with new-onset disorders did not seek any treatment after Katrina.

The negative consequences of both forms of unmet treatment needs are uncertain. Katrina survivors with mental disorders could conceivably have had their symptoms quickly dissipate without treatment and without long-term consequences. However, earlier studies have shown that most cases of posttraumatic stress disorder have durations of more than 1 year

(36), with more than one-third failing to recover after many years. Furthermore, time to remission is nearly twice as long for untreated individuals than for those receiving treatment

(19) . Dysfunction, development of comorbidity, and suicidality have been associated with even subthreshold posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms

(19,

37,

38) .

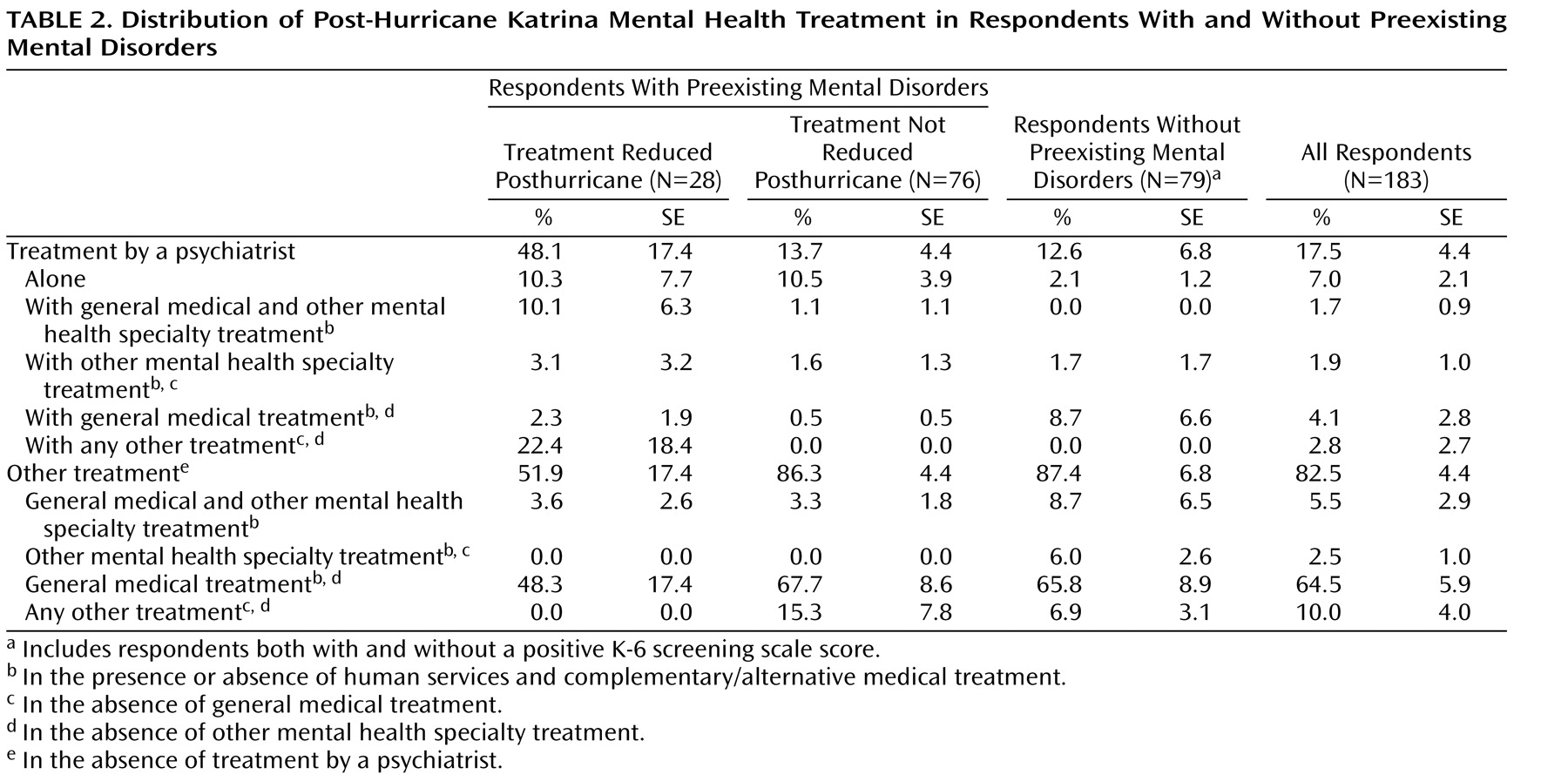

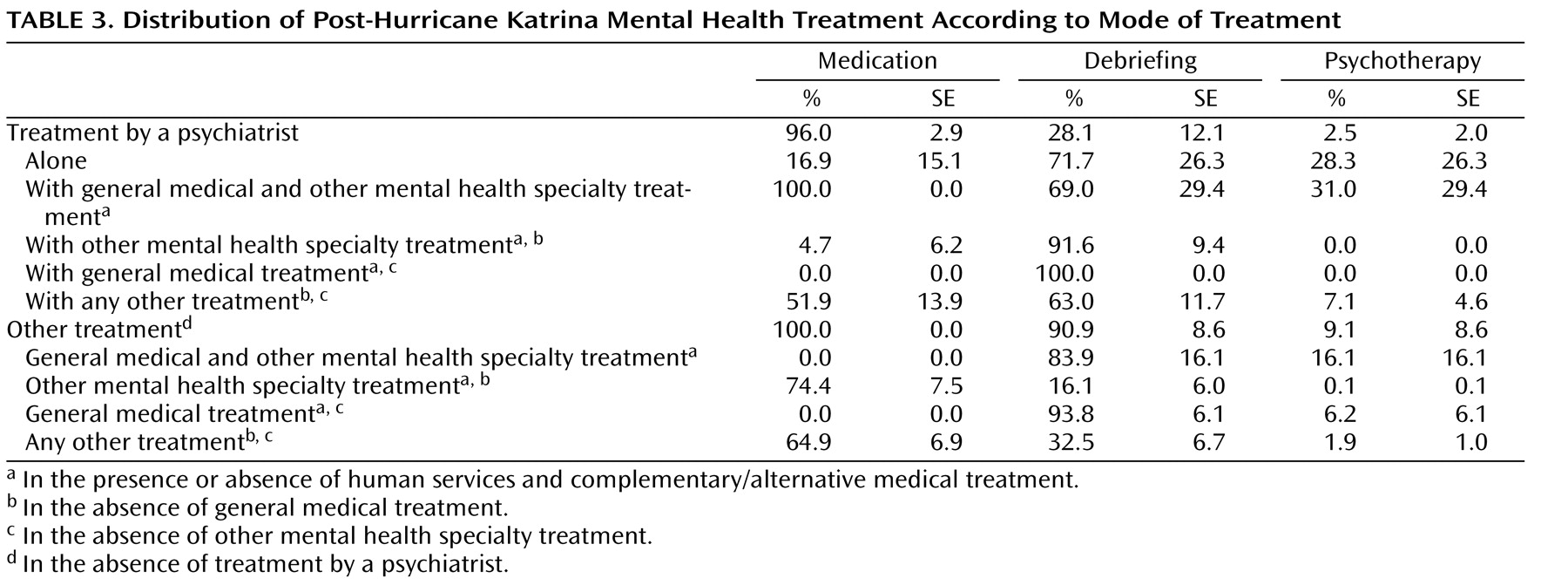

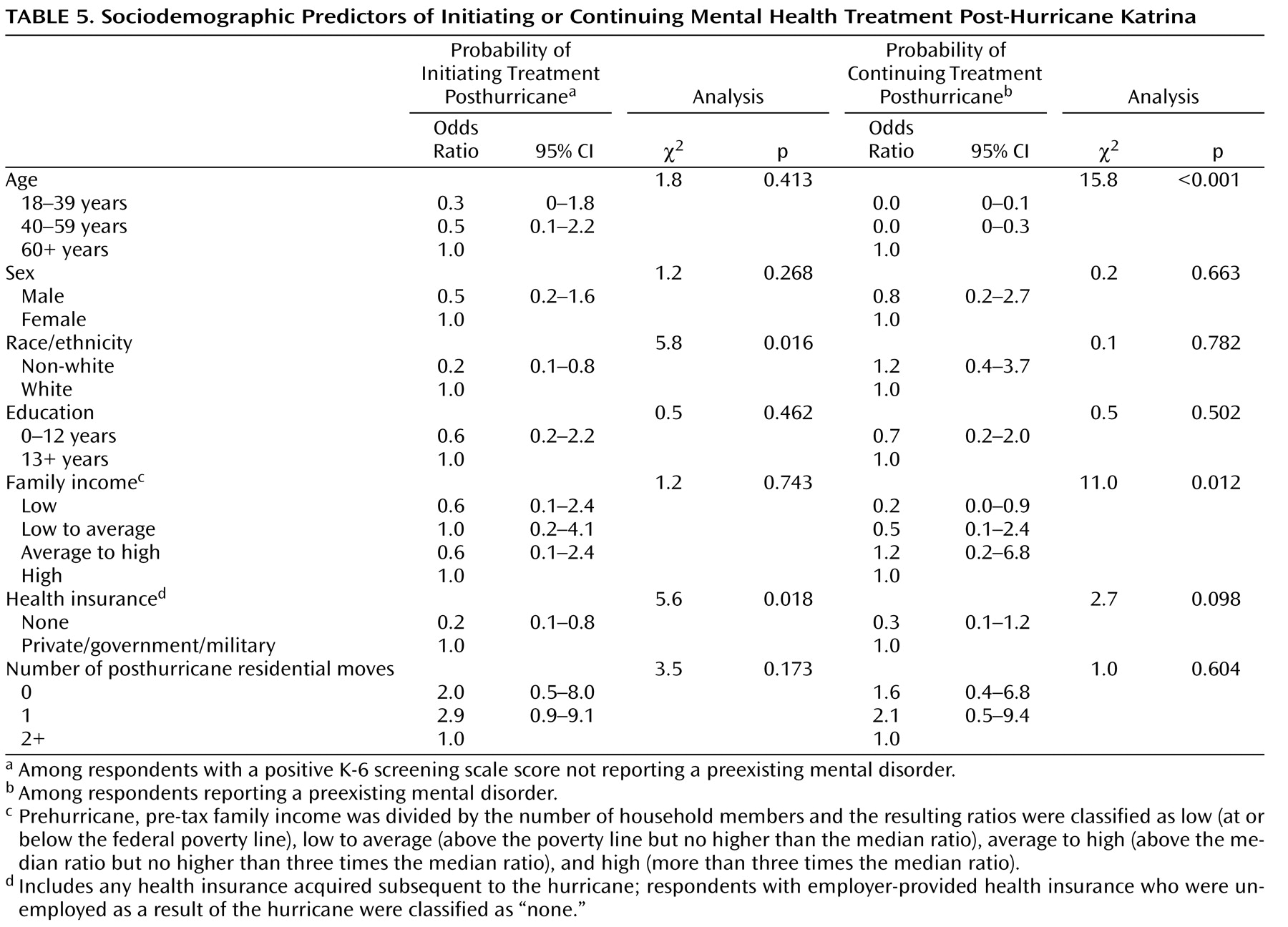

The mental health services that Katrina survivors did receive are likely to reflect both what was available at the time and patients’ preferences. Most survivors used the general medical sector for mental health care, which emphasizes the importance of training and supporting primary care personnel in delivering quality mental health treatment in disaster settings. One means of doing so might be to increase the comanagement of cases by general medical and mental health specialty personnel, a practice that was exceedingly rare among Katrina survivors. While psychiatrists saw only a small proportion of cases overall, they had provided treatment to nearly half of those with preexisting cases experiencing posthurricane disruptions in care; such findings may indicate a particular role for the psychiatry sector in ensuring treatment continuity during disasters. Pharmacotherapy was the most commonly used mode of treatment for emotional problems, suggesting that current initiatives, most importantly the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Strategic National Stockpile of emergency medications, include frequently used psychotropic classes of medication

(39) . Use of psychological counseling was much less common, despite prior research showing that this mode of treatment may be preferable to pharmacotherapy in largely underserved minority populations

(40,

41) . Psychiatrists were more likely to deliver some form of counseling, suggesting they might be useful in increasing use of psychotherapy in future disasters.