Cognitive impairment is a core feature of schizophrenia, with converging evidence showing that it is strongly related to functioning in areas such as work, social relationships, and independent living

(1,

2) . Furthermore, cognitive functioning is a robust predictor of response to psychiatric rehabilitation (i.e., systematic efforts to improve the psychosocial functioning of persons with severe mental illness)

(3), including outcomes such as work, social skills, and self-care

(1,

4,

5) . Because of the importance of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia, it has been identified as an appropriate target for interventions

(6) .

In recent years, the number of studies that examined psychosocial functioning has grown sufficiently to permit a closer look at the impact of cognitive remediation. We conducted a meta-analysis of controlled studies to evaluate the effects of cognitive remediation on cognitive functioning, symptoms, and functional outcomes. We also examined whether characteristics of cognitive remediation programs (e.g., hours of cognitive training), the provision of adjunctive psychiatric rehabilitation, treatment settings, patient demographics, or type of control group was related to improved outcomes. We hypothesized that cognitive remediation would improve both cognitive functioning and psychosocial adjustment. We also hypothesized that programs that provided more hours of cognitive training would have stronger effects on cognitive functioning and that adjunctive psychiatric rehabilitation would be associated with greater improvements in functional outcomes.

Results

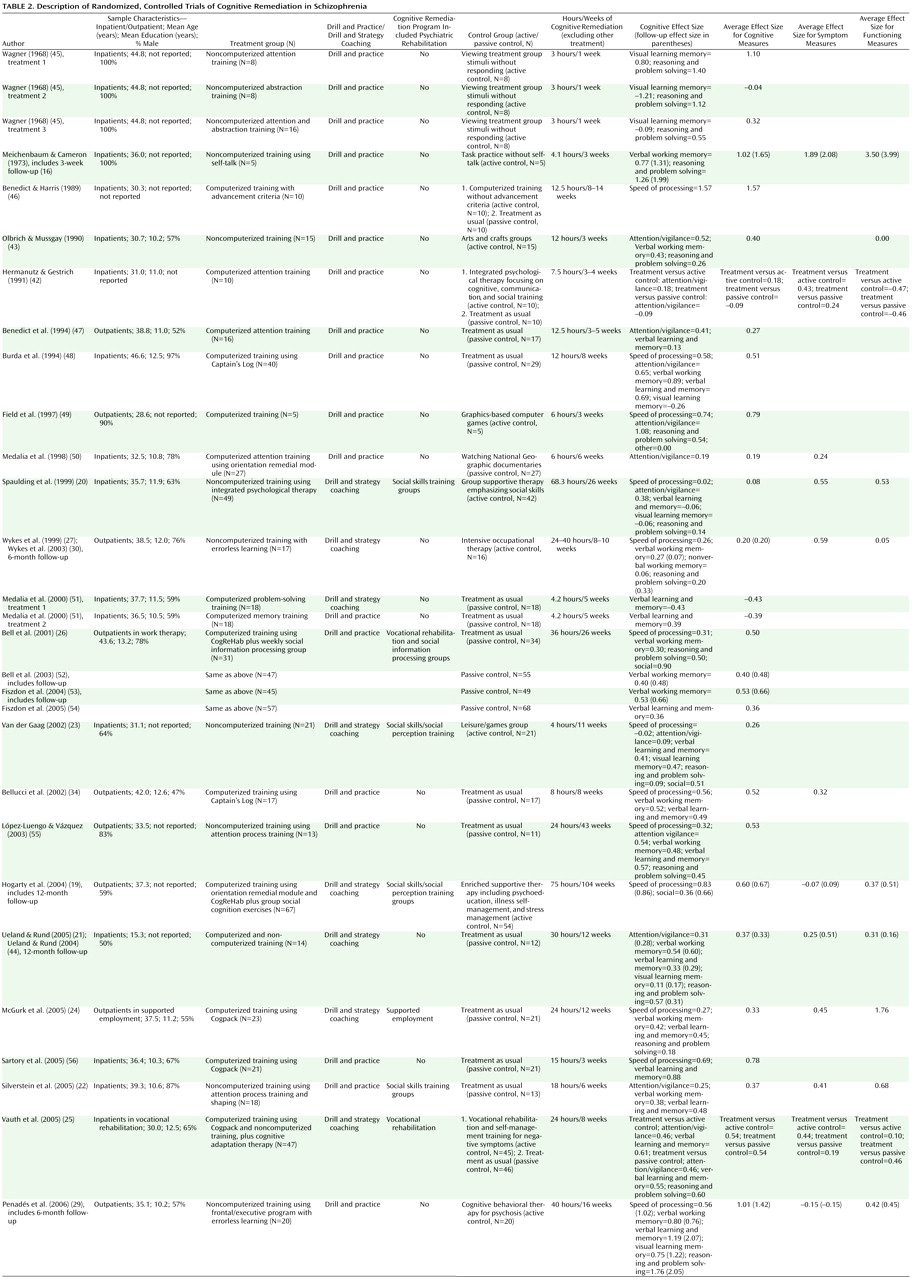

Data from 26 studies (1,151 subjects) were included. The studies, characteristics of participants and programs, and effect sizes are displayed in

Table 2 . The mean sample size was 50 (SD=36, range=10–138). The mean age of the participants was 36.3 years (SD=6.0, range of means=15–47), the mean years of education was 11.8 (SD=1.0, range of means=10–13), 69% of the participants were men, and 60% were inpatients. The mean duration of cognitive remediation programs was 12.8 weeks (SD=20.9, range=1–104). Programs targeted for training an average of 2.9 cognitive domains (SD=1.6, range=1–6), whereas changes in cognitive functioning were assessed on an average of 3.1 cognitive domains (SD=1.6, range=1–6). Sixty-nine percent of the programs used a drill and practice intervention; 23% provided adjunctive psychosocial rehabilitation.

Effects on Cognitive Performance

Only one study examined changes in nonverbal working memory

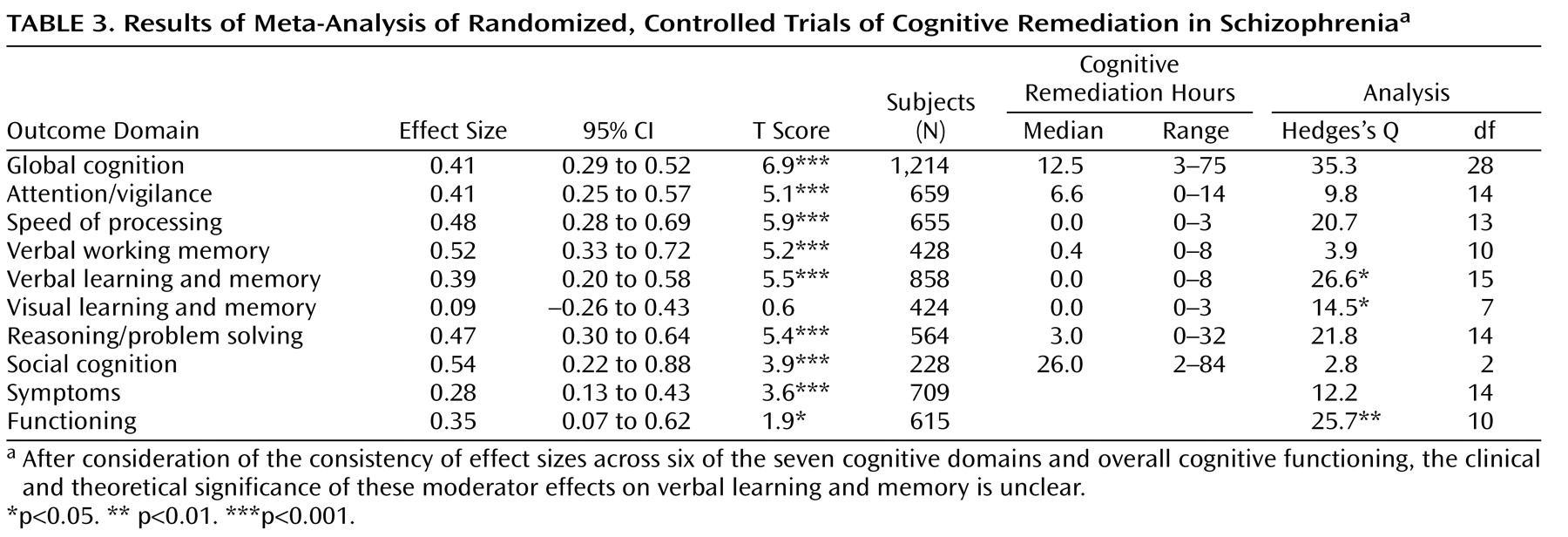

(27), so this domain was not included in the meta-analysis. The effect sizes and related statistics for overall cognition and the other seven individual cognitive domains are provided in

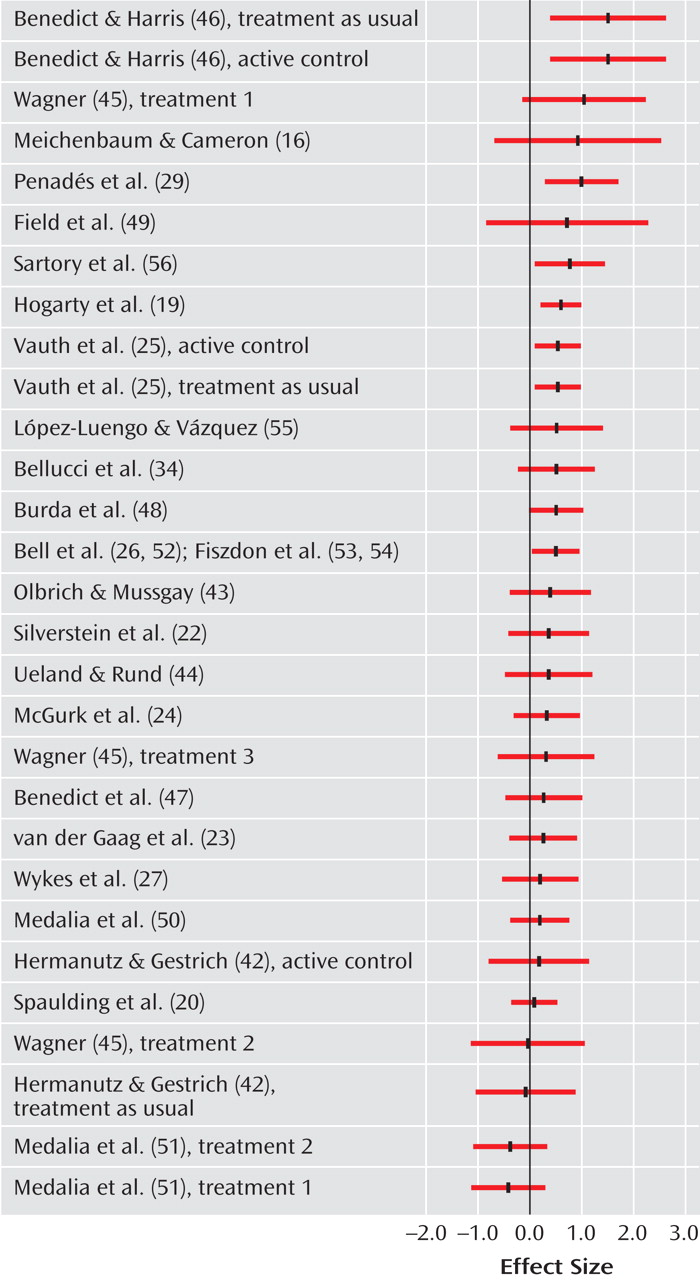

Table 3 . In addition, the effect sizes for overall cognitive functioning for each study are depicted in

Figure 1 . The effect size for overall cognition was significant, as well as for six of the seven domains of cognitive performance. Most of the effects were in the medium or low-medium effect size range, indicating improved cognitive performance after cognitive remediation. The effect size for visual learning and memory was not significant (0.09).

Six studies also reported cognitive data at follow-up

(16,

19,

21,

28 –

30) . For these studies, the average effect size at posttreatment was 0.56 (t=4.8, df=5, p<0.001, CI=0.33–0.79; Q=3.4, df=5, n.s.), and at follow-up, it was 0.66 (t=5.7, df=5, p<0.001, CI=0.43–0.89; Q=7.8, df=5, n.s.). Similar to the results at posttreatment, cognitive remediation was associated with improved overall cognitive performance an average of 8 months later.

Hedges’s Q was significant for only one cognitive domain, verbal learning and memory, indicating significant heterogeneity in effect sizes to evaluate the effects of moderators. For this domain, a larger effect size was associated with more hours of cognitive remediation (0.57) compared with fewer hours (0.29) (Q=3.7, df=1, p<0.05) and with drill and practice (0.48) compared with drill and practice plus strategy coaching (0.23) (Q=2.0, df=1, p<0.05); hours of cognitive remediation were unrelated to program type (χ 2 =0.4, df=1, n.s.).

Effects on Symptoms and Functioning

Cognitive remediation was associated with a small effect size for symptoms (0.28) and between a small and a medium effect size for functioning (0.35). There was significant heterogeneity in the effect sizes for functioning (Q=25.7, df=11, p<0.01), but not for symptoms. Moderator analyses indicated that cognitive remediation resulted in stronger effect sizes for improved psychosocial functioning in studies that provided adjunctive psychiatric rehabilitation (0.47) compared to no psychiatric rehabilitation (0.05) (Q=5.5, df=1, p<0.01.), cognitive remediation programs that used drill and practice plus strategy coaching (0.62) compared to drill and practice only (0.24) (Q=4.6, df=1, p<0.05), and studies that included older (0.55) rather than younger (0.18) patients (Q=5.7, df=1, p<0.05). Program type was unrelated to age and to adjunctive psychiatric rehabilitation, but age and adjunctive psychiatric rehabilitation were significantly associated (χ 2 =6.7, df=1, p<0.05). Studies that provided psychiatric rehabilitation tended to serve older patients.

Discussion

The results provide support for the effects of cognitive remediation on improving cognitive functioning in schizophrenia, with effect sizes in the medium range for overall cognitive functioning (0.41) and six of the seven cognitive domains (0.39–0.54). The effects of cognitive remediation on cognitive performance were remarkably similar across the 26 studies included in the analysis despite differences in length and training methods between cognitive remediation programs, inpatient/outpatient setting, patient age, and provision of adjunctive psychiatric rehabilitation. The results indicate that cognitive remediation produced robust improvements in cognitive functioning across a variety of program and patient conditions.

The effect sizes of cognitive remediation were homogeneously distributed across studies for overall cognitive functioning and six of the seven cognitive domains, precluding the examination of moderators of treatment effects for most cognitive outcomes. Thus, contrary to our hypothesis, the number of hours programs devoted to cognitive remediation was not related to the amount of improvement in overall cognitive functioning. However, hours of training, as well as use of drill and practice rather than combined drill and practice with strategy coaching, were related to improvements in verbal learning and memory, suggesting that this domain may be more sensitive to the method and extent of cognitive remediation.

It is possible that a relatively limited amount of cognitive remediation (e.g., 5–15 hours) is sufficient to produce improved cognitive functioning and that all studies provided an adequate amount of treatment. Alternatively, the amount of cognitive remediation may not be related to immediate gains in cognitive functioning but could contribute to the retention of improvements following the termination of treatment. The impact of amount of cognitive remediation on the maintenance of treatment effects could not be evaluated in this meta-analysis because only six studies conducted follow-up assessments an average of 8 months after completion of the program. However, the mean effect size for overall cognitive performance for these studies was in the medium range (0.66), comparable in magnitude to the immediate effects of cognitive remediation. These findings provide preliminary support for the longer-term benefits of cognitive remediation on cognitive performance and point to the need for more research on the maintenance of treatment effects.

The overall effect size of cognitive remediation on improving symptoms was significant but in the small range (0.28). Previous reviews of the effects of cognitive remediation either have not examined symptoms

(10,

11) or were inconclusive because of the small number of studies

(12,

13) . The apparently limited impact of cognitive remediation on symptoms is consistent with numerous studies showing that cognitive impairment is relatively independent of other symptoms of schizophrenia

(31 –

33) . Cognitive remediation may have some beneficial effects on symptoms by providing positive learning experiences that serve to bolster self-esteem and self-efficacy for achieving personal goals, thereby improving depression. Several studies have reported that cognitive remediation improved mood

(24,

27,

34) .

Cognitive remediation also had a significant effect on improving psychosocial functioning, with an average effect size of 0.35, just slightly lower than the average effect size of 0.41 for improved cognitive performance. For example, patients who participated in cognitive remediation showed greater improvements in obtaining and working competitive jobs

(24,

25), the quality of and satisfaction with interpersonal relationships

(19), and the ability to solve interpersonal problems

(20) . These findings are unique because until recently a sufficient number of studies had not measured functional outcomes from which to draw firm conclusions. The impact of cognitive remediation on improved functioning is important because the primary rationale for cognitive remediation in schizophrenia is to improve psychosocial functioning

(35) .

In contrast to the uniform effects across studies of cognitive remediation on overall cognitive performance and symptoms, there was significant variability in its effects on psychosocial functioning. Furthermore, as hypothesized, cognitive remediation programs that provided adjunctive psychiatric rehabilitation had significantly stronger effects on improving functional outcomes (0.47) than programs that did not (0.05). This effect is consistent with previous research showing that cognitive impairment attenuates response to psychiatric rehabilitation

(1,

36,

37) and suggests that improved cognitive performance may enable some patients to benefit more from rehabilitation. The findings are also consistent with the results of a meta-analysis of integrated psychological therapy

(38) in which the strongest effects on functioning were found in programs that integrated cognitive remediation and social skills training rather than programs that provided either intervention alone

(39) .

Cognitive remediation programs that included strategy coaching had stronger effects on functioning than programs that focused only on drill and practice. Strategy coaching typically targets memory and executive functions by teaching methods such as chunking information to facilitate recall and problem-solving skills. It is unclear whether strategy coaching is more effective because people are better able to transfer skills from the training setting into their daily lives

(35) or because teaching such strategies helps patients compensate for the effects of persistent cognitive impairments on functioning

(24) or both. Further research is needed to address this question.

The effects of cognitive remediation were not influenced by the nature of the control condition. Thus, simply actively or passively engaging patients in treatments designed to control for the amount of clinician contact did not appear to confer any benefit in cognitive functioning beyond the provision of usual services. These findings are consistent with the meta-analysis of the cognitive remediation-based integrated psychological therapy program

(39) but differ from the psychotherapy literature, where there is ample evidence for nonspecific effects related to therapist attention

(40) . The mechanisms underlying the effects of cognitive remediation on improved cognitive performance, functioning, and symptoms appear to differ from those involved in psychotherapy. The results raise questions about the need to control for the amount of clinician attention given to treatment control groups in research on cognitive remediation.

So what has been learned after almost 40 years of research on cognitive remediation for schizophrenia? Although a great deal more is known about schizophrenia and its neurocognitive underpinnings and the technology for assessing and remediating cognitive impairments has evolved (e.g., most programs now employ at least some computer-based training), the effect sizes on cognitive functioning do not appear to have increased appreciably in recent years. The failure to develop more potent programs could be due to limitations imposed by the illness itself and not the fault of treatment developers. It may be argued that a similar phenomenon has occurred in the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia, where despite the enormous investment of resources into the development of new drugs, the clinical gains in treating symptoms over the past 50 years are debatable

(41) .

Alternatively, the ability to improve the effectiveness of cognitive remediation may depend on attention to critical issues in research design. Two such issues deserve special consideration: the evaluation of the persistence of remediation effects on cognitive functioning and the assessment of the impact of remediation on functional outcomes. Despite the number of controlled studies of cognitive remediation, only six studies

(16,

19,

21,

28 –

30) examined whether improvements in cognitive functioning were maintained at a posttreatment follow-up, precluding the exploration of moderators of treatment effects. The relative lack of data addressing this question may be important because different program, patient, or setting factors could influence the long-term maintenance of cognitive effects compared to short-term effects.

Similarly, only 11 studies evaluated functional outcomes

(16,

19,

20,

22,

24,

25,

27,

29,

42 –

44), and this was the first meta-analysis to quantitatively demonstrate that cognitive remediation improved psychosocial functioning. Furthermore, the impact of cognitive remediation on functioning was moderated by several factors, including the provision of adjunctive psychiatric rehabilitation, cognitive training method, and patient age, suggesting potentially important factors for improving the impact of treatment programs. Thus, the ability to make cognitive remediation programs more effective may have been constrained by the neglect of most studies to measure the long-term effects of remediation and its impact on functional outcomes, resulting in the inability to identify moderators of treatment that could be the focus of efforts to hone and refine the intervention. Future research on cognitive remediation should routinely evaluate psychosocial functioning and the long-term effects of treatment on all outcomes of interest. In addition, research that systematically examines the interactions between cognitive remediation and psychiatric rehabilitation is warranted.

In summary, cognitive remediation was found to have consistent effects on improving cognitive performance, functioning, and symptoms. In addition, the impact of cognitive remediation on functional outcomes was significantly greater in studies that also provided psychiatric rehabilitation, suggesting that these two treatment approaches may work together in a synergistic fashion. These findings challenge the assumption that simply improving cognitive functioning in schizophrenia will spontaneously lead to better psychosocial outcomes. The results do suggest, however, that cognitive remediation may improve the response of some patients to psychiatric rehabilitation. Overall, this meta-analysis indicates that cognitive remediation may have an important role to play in improving both cognitive performance and functional outcomes in schizophrenia.