In their article in

The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, Mark Zimmerman, M.D., et al.

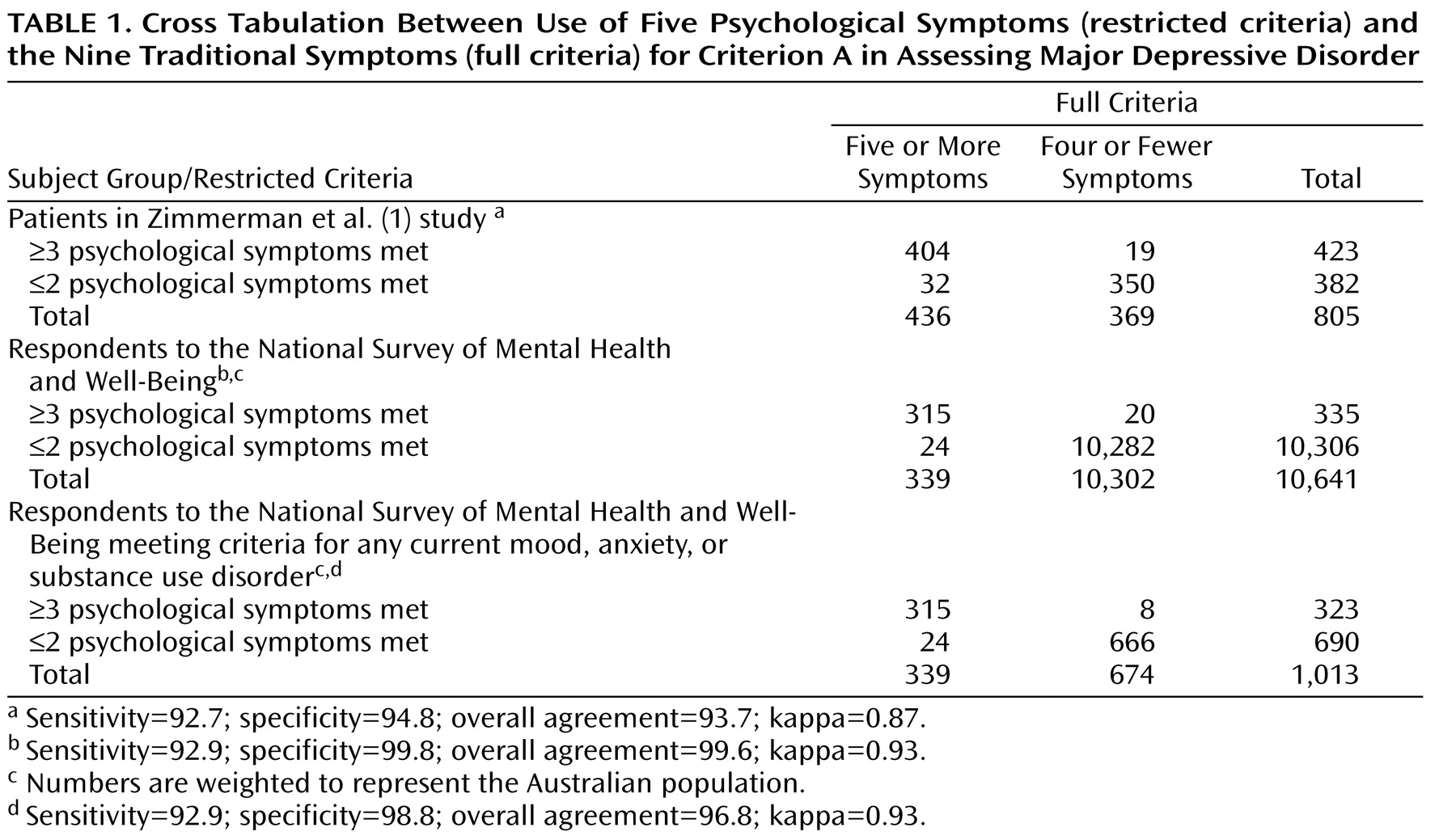

(1) argued that it might be possible to diagnose criterion A of major depressive disorder on the basis of a restricted symptom set. They used the five psychological symptoms (depressed mood, lack of interest, worthlessness, poor concentration, and thoughts of death) and found that 93.7% of patients who met criteria for five or more of the nine traditional symptoms also met the restricted criteria for three or more of the five psychological symptoms. Diagnostic accuracy was maintained. One justification for a restricted symptom set was that studies showed that few psychiatry or primary care trainees could remember the nine symptoms

(2,

3) . They tended to remember weight change and sleep disturbance, symptoms that are not unique to major depressive disorder.

The Zimmerman et al.

(1) data, recreated in

Table 1, are from their outpatient clinic, and it is impossible to be certain that the results are not specific to that sample. We replicated their finding from data from the 10,641 respondents to the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being

(4), which used the 12-month version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, Version 2.1. Nineteen percent of respondents reported 2 weeks of either depressed mood or loss of interest in the past 12 months, and all of these respondents were asked questions about every DSM-IV symptom for criterion A of major depressive disorder. Six percent met criteria for major depressive disorder during the year; one-half were current cases. The first replication (

Table 1 ) included all respondents and showed 99.6% agreement between the full and restricted definitions. The large number without major depressive disorder could have inflated the measures of agreement. In order to recreate the clinical characteristics of the Zimmerman et al. sample, we focused on the 1,013 people from the Australian survey who met criteria for current mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. This second replication (

Table 1 ) showed 96.8% agreement between the full and restricted definitions. Substantially the same people were diagnosed by the full and restricted definitions in both replications.

Many diagnostic criteria in DSM-IV are long and difficult to remember and, if simplified, may lessen the use of the not otherwise specified category. The diagnosis of depressive disorder not otherwise specified is used more commonly than the diagnosis of major depressive disorder in both primary and specialty care

(5 –

7) . It is conceivable that many people who receive a depressive disorder not otherwise specified diagnosis are subthreshold and warrant treatment, but in one primary care study

(8), 70% of people receiving a diagnosis of depressive disorder not otherwise specified qualified for specific diagnoses when Research Diagnostic Criteria were applied. A diagnosis of depressive disorder not otherwise specified was intended as a default option and contains little clinical information. There may be some clinical utility in simplifying the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder if clinicians could remember and ask about the restricted symptom set and be less likely to fall back on inappropriate use of the depressive disorder not otherwise specified option.