Emotion recognition deficits in schizophrenia are well established (see references

1 –

4 for reviews) and are strongly related to social functioning

(5) . Because these deficits are related to abnormal brain function in a complex neural network underlying face processing and emotion recognition

(6), understanding them may help elucidate the neurobiological underpinnings of schizophrenia.

Emotion recognition deficits have been related to clinical and behavioral features as well as neural measures, and in recent years cultural, racial, and ethnic influences on emotion processing have been explored. For example, Brekke and colleagues

(7) reported that Caucasians with schizophrenia performed better on a facial emotion perception task than African American and Latino patients. Similarly, Habel et al.

(8) reported better emotion discrimination abilities among American and German participants compared with Indian participants. While these studies appear to support an emotion recognition advantage for Caucasians with schizophrenia, they both failed to address a potential confound by including only Caucasian faces as stimuli. This confound becomes particularly important when considering a large literature from healthy individuals demonstrating clear cross-racial effects for face memory and emotion recognition. An other-race effect has been established indicating that memory for, and discrimination among, other-race faces is impaired relative to own-race faces

(9) . A meta-analysis of culture and emotion perception revealed an in-group advantage such that accuracy of emotion identification is higher when the perceiver is the same race as the person expressing the emotion (i.e., the stimulus)

(10) . Such cross-racial effects may have confounded previous results, artificially inflating between-group differences and suggesting disproportionately greater impairments in non-Caucasian individuals with schizophrenia.

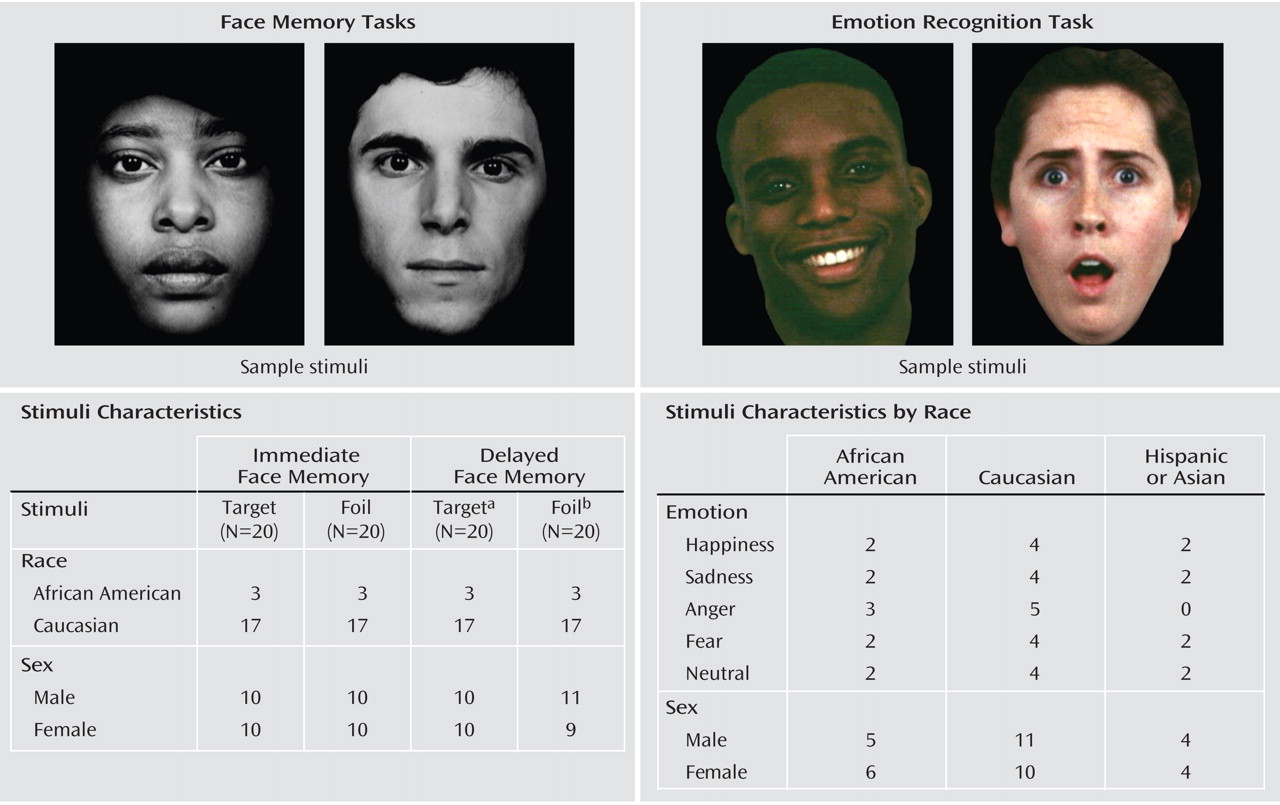

In this study, we address this potential confound by evaluating the presence of an other-race effect for face and emotion processing in individuals with schizophrenia. Caucasian and African American patients with schizophrenia and healthy community comparison subjects completed tasks of face recognition memory and facial emotion identification that included both Caucasian and African American faces as stimuli. It was anticipated that compared with the healthy comparison subjects, patients would show impairments in both face memory and emotion identification. The presence of an other-race effect was explored by examining participant race by stimulus race interactions in both face memory and emotion recognition. Such interactions would indicate the extent to which patients and healthy comparison subjects perform disproportionately worse at identifying emotions and recognizing previously seen faces when the participant and stimulus faces are of a different race. An other-race effect in schizophrenia would show a normative sensitivity to same- versus other-race cues in faces, which would contrast with the marked face processing deficits observed in individuals with this disorder.

Results

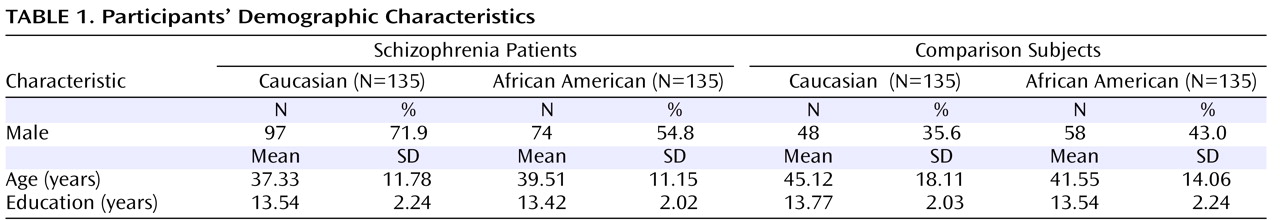

As expected, the four groups differed significantly in sex distribution (χ

2 =40.64, p<0.001), with a greater proportion of males in the patient groups (

Table 1 ). They also differed in age (F=7.51, df=3, 536, p<0.001), with Caucasian comparison subjects being older on average than both Caucasian (p<0.001) and African American patients (p=0.006).

Face Memory

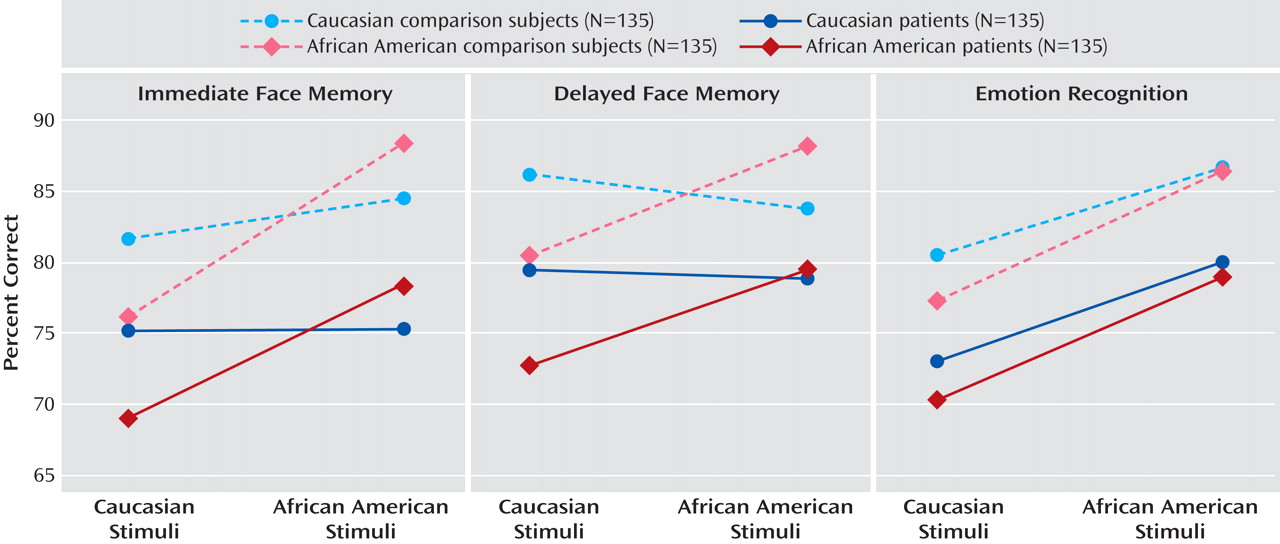

For immediate face memory, there was a significant main effect for group, demonstrating that comparison subjects had better target recognition than participants with schizophrenia (mean=82.7% and mean=74.5%, respectively; F=69.16, df=1, 531, p<0.001; partial eta-squared [ η p 2 ]=0.115). Main effects were also evident for stimulus race and stimulus sex such that African American faces were better remembered than Caucasian faces (mean=81.7% and mean=75.5%, respectively; F=6.75, df=1, 531, p=0.01; η p 2 =0.013) and male faces were better remembered than female faces (mean=85% and mean=72.2%, respectively; F=46.33, df=1, 531, p<0.001; η p 2 =0.08). Notably, there was no main effect of participant race or sex.

As predicted, there was a significant interaction between stimulus race and participant race (F=46.00, df=1, 531, p<0.001; η

p 2 =0.08), showing an other-race effect: Caucasian participants remembered both Caucasian and African American faces equally well, while African American participants remembered African American faces better than Caucasian faces (

Figure 2 ). This interaction did not differ across groups (schizophrenia patients and comparison subjects), and there was no significant three-way interaction by group. Additionally, the interaction between stimulus sex and participant sex was not significant, indicating that participants did not better remember same-sex faces.

Performances on delayed face memory were similar. Comparison subjects remembered more faces than did schizophrenia patients (mean=84.6% and mean=77.6%, respectively; F=44.94, df=1, 531, p<0.001; η

p 2 =0.078), and male faces were better remembered than female faces (mean=82.8% and mean=79.4%, respectively; F=16.11, df=1, 531, p<0.001; η

p 2 =0.029). The main effect of stimulus race was no longer significant, nor were main effects of participant race or sex. More important, the interaction between stimulus race and participant race was again significant (F=42.66, df=1, 531, p<0.001; η

p 2 =0.074), demonstrating that both African American and Caucasian participants better remembered same-race faces (

Figure 2 ). Again, this other-race effect did not differ between the schizophrenia patients and comparison subjects, as indicated by a nonsignificant three-way interaction with group. Finally, in delayed memory, there was also a significant stimulus sex by participant sex interaction (F=6.57, df=1, 531, p=0.011; η

p 2 =0.012) such that males were more likely to remember male faces and females were approximately equally likely to remember both male and female faces. This effect did not differ across groups. Thus, in delayed memory, all participants better remembered faces of their own race as compared with other-race faces, and male participants showed an advantage for remembering male faces.

Emotion Recognition

Comparison subjects again scored better than patients in emotion recognition (mean=82.8% and mean=75.6%, respectively; F=48.11, df=1, 531, p<0.001; η

p 2 =0.083). A main effect of stimulus race was also apparent (African American faces: mean=83%; Caucasian faces: mean=75.3%; F=13.97, df=1, 531, p<0.001; η

p 2 =0.026), indicating that African American stimuli were more likely to be accurately labeled than Caucasian stimuli, and there were no significant main effects for stimulus sex or participant sex. Contrary to previous work

(7,

8), there was no main effect for participant race. Instead, there was a significant interaction between stimulus race and participant race (F=3.99, df=1, 531, p=0.046; η

p 2 =0.007), demonstrating that African American participants were worse than their Caucasian counterparts in identifying emotion on Caucasian faces but performed equally well on African American faces (

Figure 2 ). As with face memory, this effect did not differ between patient and comparison groups. Lastly, the interaction between stimulus sex and participant sex was not significant.

Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to assess the other-race effect, or differential abilities in processing same- versus other-race faces, in schizophrenia. The magnitude of this phenomenon could account for previous reports of greater impairment in emotion perception abilities among non-Caucasian compared with Caucasian individuals with schizophrenia when Caucasian stimuli were used. We found evidence supportive of an other-race effect in both comparison subjects and patients. In immediate face memory, African American participants were more likely to recognize same-race faces than other-race faces, and in delayed face memory, all participants better recognized faces of their own race as compared with other-race faces. Likewise, on emotion recognition, both African American and Caucasian participants performed similarly when identifying emotion on African American faces, but African American participants—in both the patient and comparison groups—performed disproportionately worse on Caucasian faces. These interactions demonstrate the presence of an intact other-race effect in schizophrenia that affects both face memory and emotion recognition.

Two previous studies

(7,

8) found that in patients with schizophrenia, Caucasians performed better on emotion recognition tasks than non-Caucasians. Whereas these studies used only Caucasian stimuli, our tasks included stimuli with both Caucasian and African American faces and failed to find a main effect of race in comparison subjects or patients. Notably, had we analyzed only responses to Caucasian stimuli, our results would have replicated those of the previous studies. Instead, our findings indicate that an other-race effect may account for the differences described in these earlier studies and highlight an important measurement issue in the extension of face processing and emotion research to clinical populations.

Because African American patients did not differ from their Caucasian counterparts after cross-racial effects were considered, the two groups appear equally impaired on face and emotion recognition and are thus likely to show similar dysfunction in neural regions underlying these abilities. The fusiform face area, thought to be an experientially modulated region of the brain implicated in face specialization

(19), shows sensitivity to racial information in healthy individuals

(20) . While individuals with schizophrenia demonstrate reduced activation in the fusiform face area

(21), the presence of an intact other-race effect suggests that this brain region may also show differential activation in patients, depending on race. Likewise, the amplitude of the face-specific N170 component of the visual event-related potential response is modulated by stimulus race

(22) . Recent work demonstrates smaller N170 responses in individuals with schizophrenia while viewing faces

(23), but again, it is possible that patients may show modulation of this response based on race. Such findings would not only mirror the behavioral findings reported here but would suggest a potentially interesting dissociation between functionally normal patterns of face processing within the context of overall deficits.

While individuals with schizophrenia are impaired in a wide range of face processing abilities, including orienting to faces

(24), visual scanning

(25), face memory, and facial emotion recognition, the presence of an intact other-race effect in schizophrenia suggests a normative developmental pattern. An other-race effect can be found in very young children

(26), and it increases over the course of childhood

(27) . These developmental changes suggest that the other-race effect may be experientially related and driven by a disproportional exposure to same-race faces relative to other-race faces during childhood

(28 –

30) . Thus, despite face processing deficits in other domains, the other-race effect exhibited by individuals with schizophrenia in this study may reflect normative developmental experience with faces and perhaps even normative development of the neural mechanisms of face processing. It would be informative, therefore, to compare individuals with schizophrenia to individuals with other neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism who similarly show face processing deficits in adulthood

(31,

32) but demonstrate qualitative and quantitative deficits with facial experience throughout childhood

(33,

34) .

In addition to a significant other-race effect, individuals with schizophrenia also showed expected impairments in both face memory and emotion recognition relative to comparison subjects. Although our results cannot speak to the specificity of face processing impairments or the magnitude of face memory deficits compared with nonface or verbal memory, it is interesting to note that both groups performed better on delayed face memory relative to immediate memory. This finding is consistent with previous work using a recognition paradigm with both face stimuli

(35,

36) and other spatial stimuli

(37) . The effect likely occurs because presenting all target stimuli for a second time in the immediate memory condition may enhance recognition during the delayed task.

While this study offers new information about face processing abilities in schizophrenia, some limitations should be considered. First, the tasks used were not specifically designed to examine an other-race effect and included fewer African American stimuli than Caucasian stimuli. Although this design still meets requirements for adequately testing an in-group advantage as espoused by Matsumoto

(38) and Elfenbein and Ambady

(39), the disparity in our task compositions may help explain some of the unexpected findings, such as a main effect for stimulus race in the immediate face memory and emotion recognition tasks. It is possible that the smaller number of African American faces caused them to be perceived as more novel and salient, thus resulting in better performance for these stimuli. However, because performance on African American faces differed as a function of participant race, the unexpected main effect for stimulus race does not affect the other-race effect findings. Similarly, the presence of an other-race effect even with unequal numbers of Caucasian and African American stimuli suggests a robust phenomenon that should be considered in future studies and further clarified with balanced stimuli. Second, face memory stimuli were presented in gray-scale images, whereas emotion recognition stimuli were presented in color images. To our knowledge, no studies have examined whether the color format of face stimuli influences the other-race effect; however, this possibility merits further study.

These limitations notwithstanding, our findings show that despite overall impairments in face memory and emotion recognition, individuals with schizophrenia demonstrated a pattern of cross-racial effects similar to that of healthy people, suggesting normative experiences with faces during development. These results also reveal an important methodological concern in measurement of face processing abilities in individuals with schizophrenia that should be considered in task development and in future investigations.