In the present study, we examined three key issues in diagnosing posttraumatic psychopathology in young children, each with broad implications for the field of developmental psychiatry. First, we sought to replicate and extend research pertaining to the validity of an alternative algorithm for diagnosing PTSD in young children based on parent report

(14,

15) . Second, we examined the potential complementary roles of parent and child informants in the diagnostic process

(27) . Finally, we assessed and compared the predictive utility of alternative algorithm PTSD and the extant DSM-IV diagnosis for the acute posttraumatic phase (acute stress disorder) in identifying those children who are most at risk for developing later-onset alternative algorithm PTSD or the chronic phase of DSM-IV PTSD. The study benefited from 1) the use of a large untreated sample, 2) the adoption of a longitudinal design, 3) the use of formal diagnostic methods in both the acute and chronic phases, and 4) the comparison of preschool- and elementary school-age children.

Alternative Algorithm PTSD Based on Parent Report

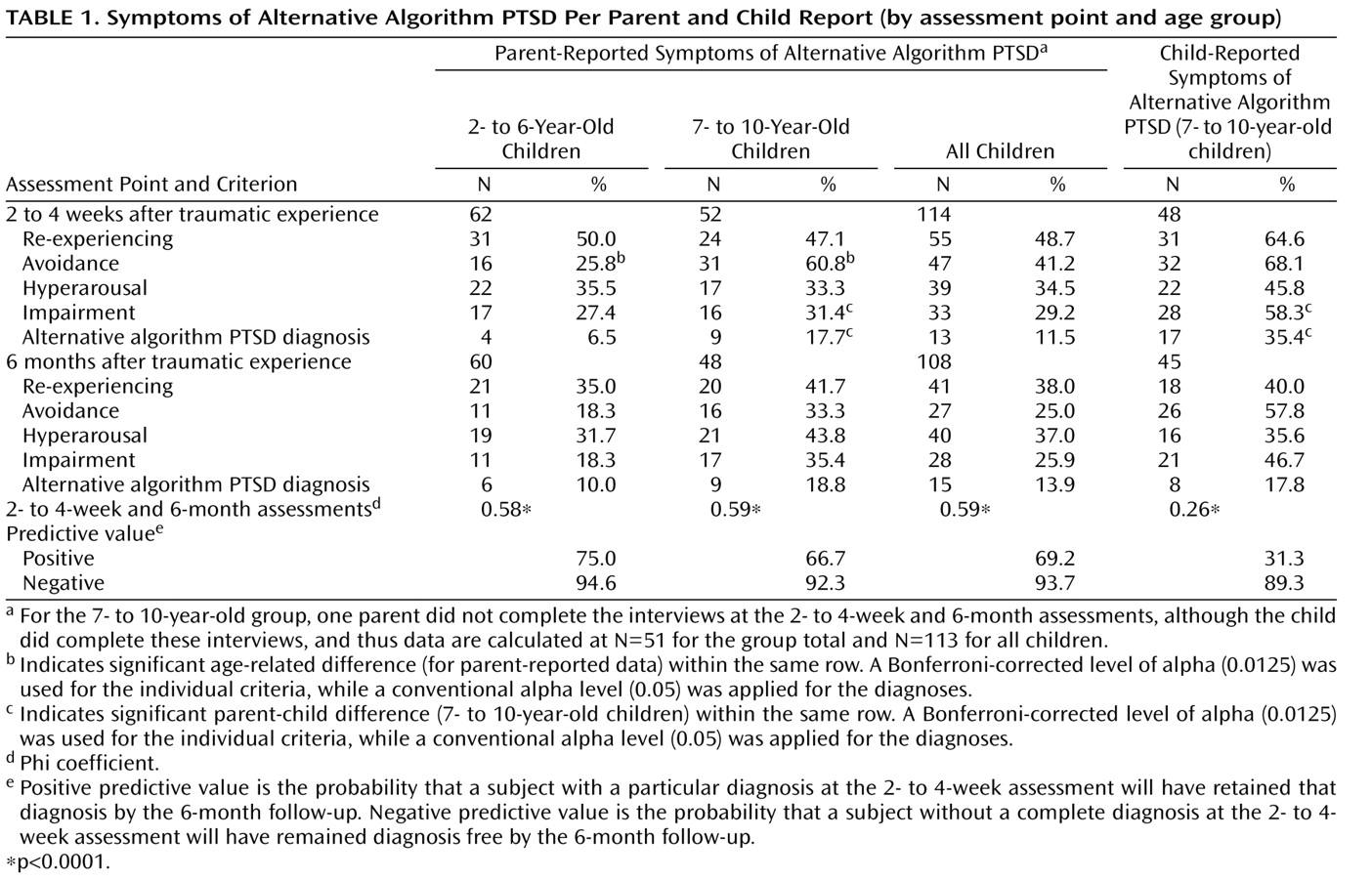

At the 6-month follow-up, the prevalence rates for a diagnosis of alternative algorithm PTSD based on parent report were consistent with those of existing findings

(18,

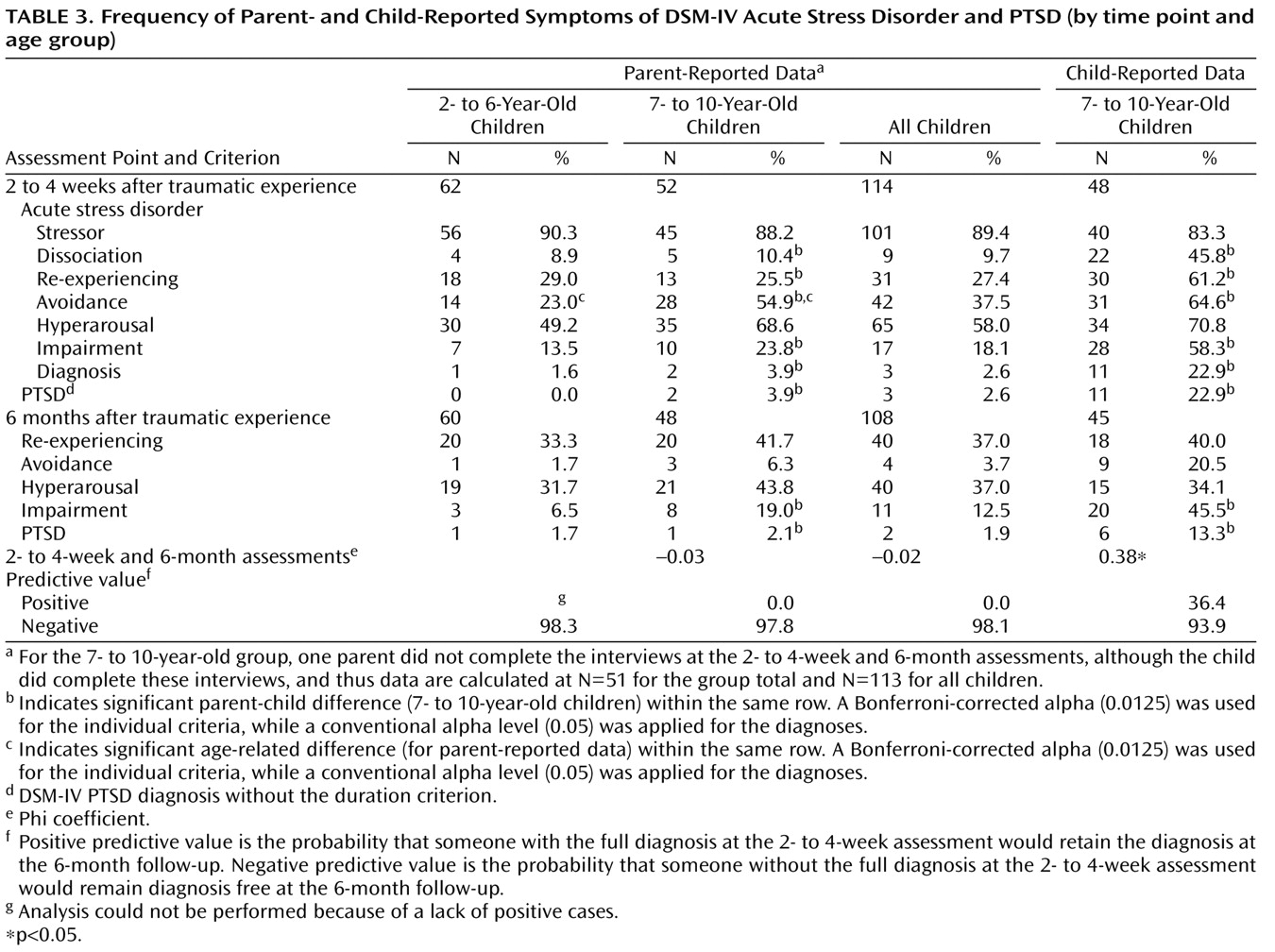

19), with approximately 14% of subjects meeting diagnostic criteria. In contrast, the prevalence rates for the established PTSD diagnosis based on parent report was <2%. This differential pattern was similar in our assessment of both 2- to 6-year-old and 7- to 10-year-old children. The higher prevalence rates for alternative algorithm PTSD from parent report for both age groups at the 6-month follow-up was not simply the result of reduced symptom requirements, since the number of symptoms endorsed for alternative algorithm PTSD from parent report was not significantly less than that endorsed for DSM-IV PTSD from parent report.

In the acute posttraumatic phase (within the first month following a traumatic event), the prevalence rates for 1) alternative algorithm PTSD from parent report and 2) the standard DSM-IV diagnosis for this acute period (acute stress disorder from parent report) in 2- to 6-year-old children were 6.5% and 1.6%, respectively. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to report such data for this age group. There was a similar differential pattern among 7- to 10-year-old children (alternative algorithm PTSD from parent report: 17.7%; acute stress disorder from parent report: 3.9%, respectively), which is consistent with findings at the 6-month follow-up. The higher prevalence rates for alternative algorithm PTSD from parent report at the initial assessment were not simply a result of parents failing to report the requisite dissociative symptoms for a diagnosis of acute stress disorder based on parent report, since the prevalence of a diagnosis of PTSD based on parent report at the initial assessment (without the duration criterion), which does not require the presence of dissociation, was similarly low (<4%).

The diagnosis of alternative algorithm PTSD based on parent report was stable between time points

(35), with 69% of children who were diagnosed at the initial assessment retaining the diagnosis at the 6-month follow-up (positive predictive value). This finding demonstrates—for the first time—that a significant degree of psychopathology, as indexed by the alternative algorithm, persists over the first 6 months posttrauma in young children. This was not the case for the diagnosis of DSM-IV PTSD based on parent report, in which no children who were diagnosed at the initial assessment retained the diagnosis at the 6-month follow-up. However, all parent report diagnoses at both the initial assessment and 6-month follow-up showed good convergent validity with the Pediatric Emotional Distress Scale.

Our data provide further support for the alternative algorithm for diagnosing PTSD based on parent report in very young children (age range: 2–6 years). These data replicate the findings of studies that used this symptom algorithm in the assessment of 2- to 6-year-old children in the acute posttraumatic phase

(8,

15), showing the superior ability of the alternative algorithm to detect clinically significant psychopathology relative to the extant DSM-IV PTSD diagnosis. This pattern is parallel to our data regarding alternative algorithm PTSD from parent report in older children (age range: 7–10 years) and thus replicates earlier preliminary findings

(8), although with a larger sample. Our results extend the research on alternative algorithm PTSD based on parent report to include the acute posttraumatic phase, providing a comparison with acute stress disorder from parent report, in which, once again, the alternative algorithm notably identified more cases relative to the standard DSM-IV algorithm. The present data also provide the first evidence of diagnostic stability for alternative algorithm PTSD from parent report during the first 6 months posttrauma in children, showing stability over a time span <2 years (cf. 19). In addition, the present study is the first to report an untreated sample of children for whom the alternative diagnostic algorithm performed favorably relative to the existing DSM-IV algorithms. Demonstrating stability in any alternative diagnostic algorithm is a key criterion of illness validity

(35) and is particularly important in younger populations given the rapidity of developmental changes in these populations.

The present data, combined with previous findings on alternative algorithm PTSD based on parent report

(6,

8), are a paradigmatic illustration of the benefit of considering alternative diagnostic algorithms in diagnosing psychopathology in young children, for whom there is increasing emphasis on the need for caution in simply “down-ageing” the existing DSM taxonomy and in the application of categorical diagnosis

(4,

20) . Furthermore, the present findings indicate that alternative algorithms that are validated in very young samples of children may offer comparable (and sometimes superior) validity in older children for whom DSM diagnoses have already been established but for whom the validity of alternative algorithms has been rarely examined.

Informant Validity

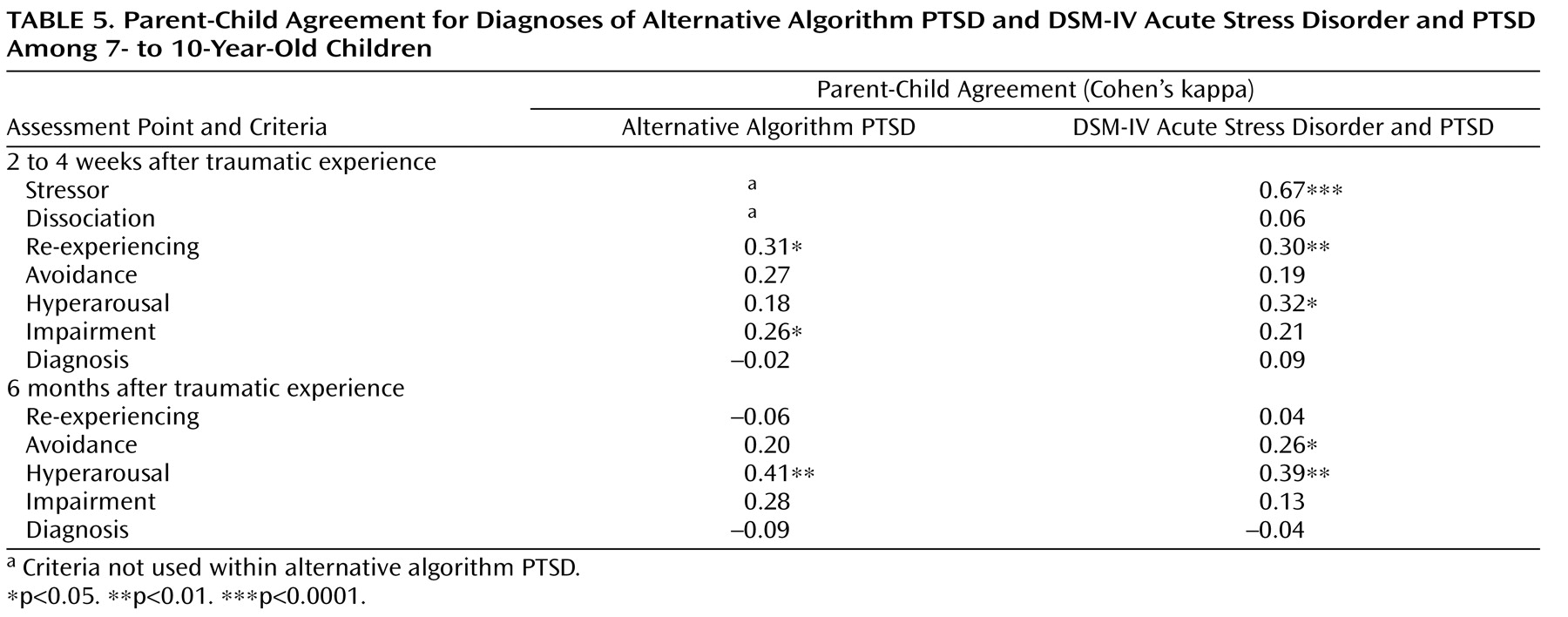

For 7- to 10-year-old children in our study sample, we were able to examine the potential complementary contributions of child- and parent-reported data. At the levels of diagnoses and individual symptom clusters, parent-child agreement was generally poor for alternative algorithm PTSD and DSM-IV acute stress disorder and PTSD, replicating previous findings for DSM-IV acute stress disorder and PTSD

(28,

37,

38) as well as for anxiety disorders in general

(39) and extending these diagnoses—for the first time—to alternative algorithm PTSD. These findings suggest that parents and children contributed different data to the diagnostic process

(27) . According to their own reports, 35.4% of children met criteria for alternative algorithm PTSD per child report at the initial assessment, and 17.8% met criteria at the 6-month follow-up. In addition, 22.9% met criteria for acute stress disorder per child report at the initial assessment, and 13.3% met criteria for PTSD per child report at the 6-month follow-up. These child-reported prevalence rates were significantly higher than parent-reported prevalence rates. However, the diagnostic stability of the diagnosis of alternative algorithm PTSD per child report was notably lower than that for the parent report diagnosis, with only 31.3% of those who were diagnosed at the initial assessment continuing to meet criteria at the 6-month follow-up. The diagnostic stability of DSM-IV diagnoses for acute stress disorder per child report and PTSD per child report was also modest (36.4%), but markedly higher than that for the parent report diagnoses.

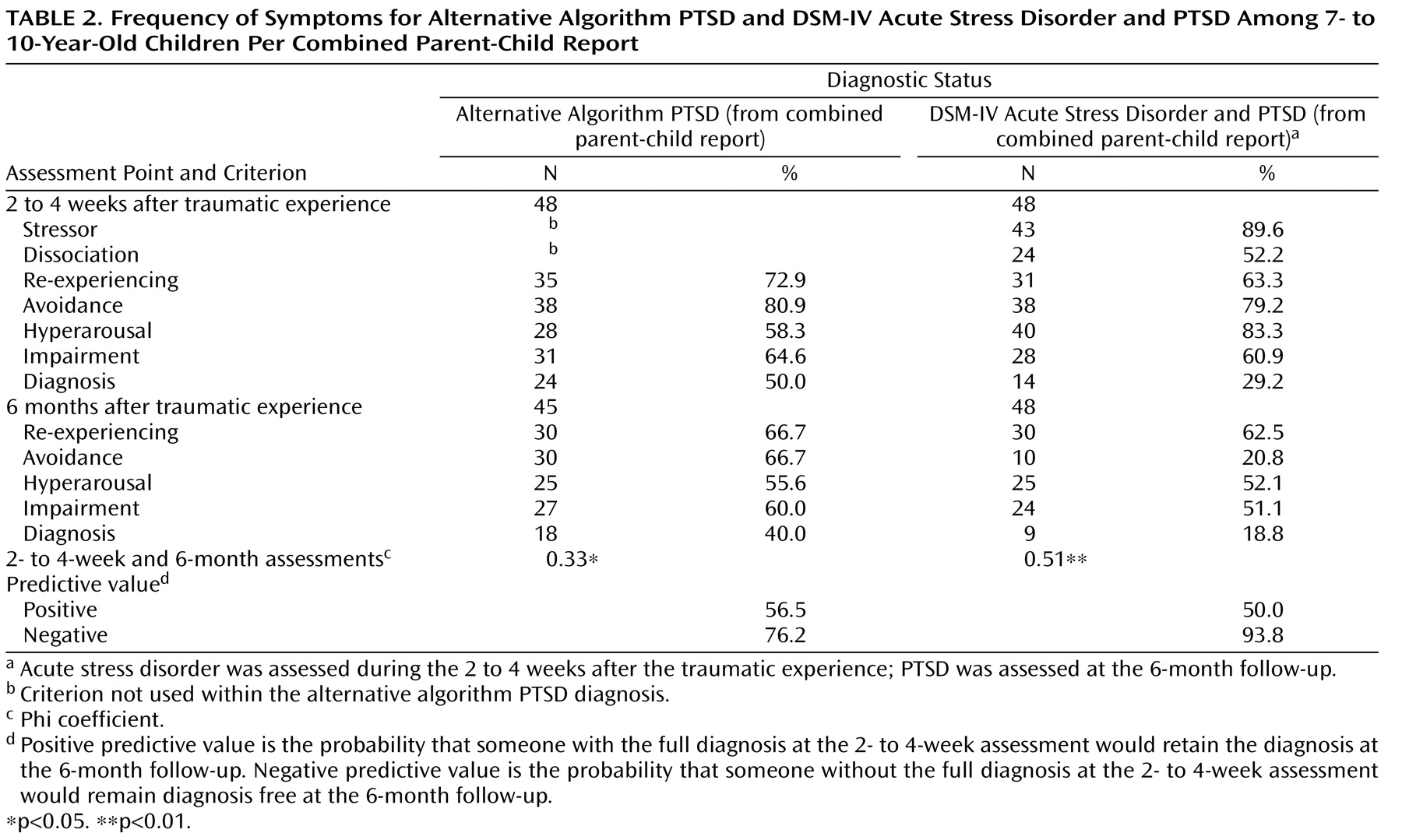

Relative to child and parent report alone, the use of combined parent-child report (with the “or” rule) in the assessment of 7- to 10-year-old children increased the prevalence rates in this age group. In addition, diagnostic stability using combined parent-child report was greater than that for child report alone, with more than one-half of the children who were diagnosed at the initial assessment retaining their diagnosis at the 6-month follow-up, regardless of whether criteria for DSM-IV acute stress disorder per combined parent-child report and PTSD per combined parent-child report or alternative algorithm PTSD per combined parent-child report were used.

In the assessment of 7- to 10-year-old children, both the use of child report and integration of child and parent report using the “or” rule resulted in an increased number of subjects being identified with posttraumatic psychopathology relative to parent report alone, although this led to reduced diagnostic stability for alternative algorithm PTSD. These data 1) further indicate the benefit of moving beyond single-informant diagnosis in order to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of clinical needs in the assessment of child psychopathology

(27) and 2) strongly suggest that in situations in which only one informant is available (e.g., among 2- to 6-year-old children in the present study), clinically significant cases are overlooked.

Early Detection

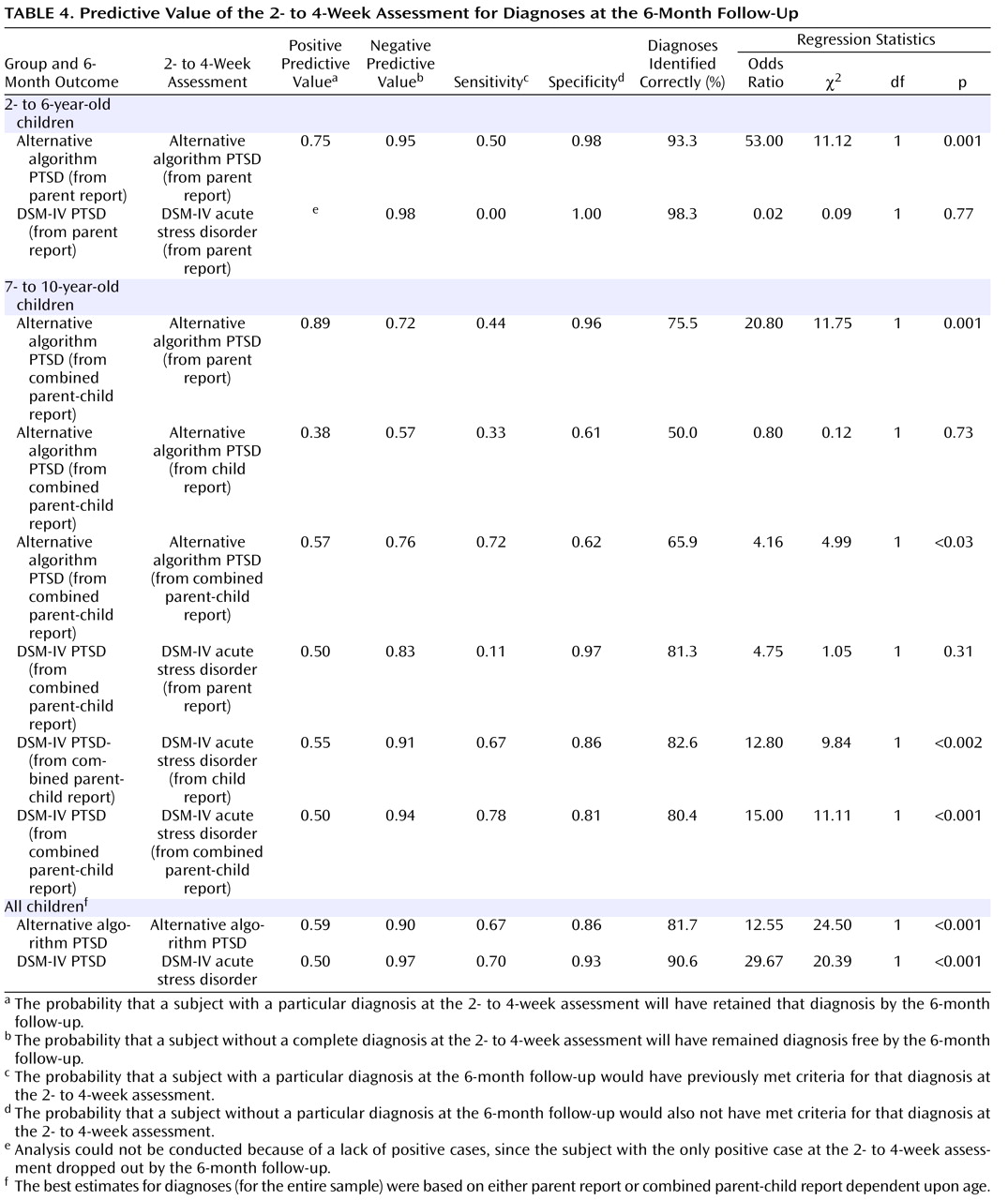

For 2- to 6-year-old children, alternative algorithm PTSD based on parent report assessed during the acute posttraumatic phase was a more sensitive predictor of 6-month follow-up diagnoses than was acute stress disorder based on parent report, although even the alternative algorithm failed to detect 50% of positive 6-month follow-up cases. Alternative algorithm PTSD from parent report was also more sensitive than alternative algorithm PTSD per child report in detecting diagnoses among 7- to 10-year-old children, with the latter diagnosis only identifying one-third of positive 6-month follow-up cases. However, for existing DSM-IV diagnoses, the opposite pattern was observed among 7- to 10-year-old children, with acute stress disorder per child report being a more sensitive predictor (detecting 67% of positive cases at the 6-month follow-up) than was acute stress disorder from parent report (detecting 11% of positive cases at the 6-month follow-up).

Combined parent-child report diagnoses were superior predictors relative to diagnoses based on parent or child report alone, with both alternative algorithm PTSD per combined parent-child report and DSM-IV acute stress disorder per combined parent-child report detecting >70% of positive cases at the 6-month follow-up. In the case of acute stress disorder per combined parent-child report, positive predictive value and specificity were comparable with the best single-informant diagnosis (acute stress disorder per child report). However, this was not the case for alternative algorithm PTSD from combined parent-child report, for which the superior sensitivity was associated with markedly lower positive predictive value and specificity relative to the best single-informant diagnosis (PTSD from parent report). This appears to have been the result of the influence of integrated child-reported data, which suggests an “overdetection” by children of diagnoses at the initial assessment (which were not subsequent diagnoses at the 6-month follow-up).

In summary, these patterns indicate that in the assessment of preschool-age children, for whom parent report alone is used, alternative algorithm PTSD based on parent report is a better measure for early detection than acute stress disorder based on parent report, although only modestly effective. In the assessment of older elementary school-age children, for whom both parent and child can be interviewed, our data indicate that combined parent-child report is optimal and that acute stress disorder per combined parent-child report is a better measure than alternative algorithm PTSD per combined parent-child report, since it is both more sensitive (detecting nearly 80% of 6-month follow-up diagnoses) and specific.

The relatively stronger predictive data for the combined parent-child report diagnosis testifies to the importance of aggregating data across different informants. Nevertheless, the overall modest levels of specificity for full diagnoses derived using clinical interview at the initial assessment, combined with the relative difficulty in obtaining such diagnoses easily and quickly in the clinic, indicate that more research is required to develop valid and sensitive simple detection instruments—perhaps involving identification of a small number of key symptoms

(24) or the use of readily administered questionnaire instruments

(40) .

There are several limitations to the present study. First, the use of a sample of children who were exposed to a common single-incident stressor necessarily suggests caution in generalizing the data to survivors of more chronic trauma, such as abuse, or of large-scale natural disasters. Second, the fact that the 6-month follow-up assessment was conducted by the same assessor who conducted the initial assessment, while providing continuity, means that the 6-month follow-up assessment was not conducted blind to the initial assessment status. Last, the study would have benefited from more data regarding comorbid posttraumatic diagnoses.

In conclusion, the present study provides clear data in favor of the adoption of the alternative algorithm criteria for PTSD based on parent report in the assessment of psychopathology among 2- to 6-year-old children, replacing the established DSM-IV criteria for PTSD. For this age group, PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria per parent report identified more cases of posttraumatic psychopathology—not simply because it requires a lower symptom count—and showed better predictive validity and stability over a 6-month period. However, for 7- to 10-year-old children, our aggregate findings between informants suggest that (assuming that parent- and child-reported data are available) the alternative algorithm does not offer a clear advantage over the established DSM-IV diagnoses for acute stress disorder and PTSD based on combined parent-child report. Thus, there is not compelling evidence in this older age group to relinquish the established DSM-IV diagnoses.