Maternal depression is a risk factor for child psychopathology that is consistent and well-replicated. The disorders among children of women with maternal depression vary according to the developmental stage of the affected offspring, with the average age at onset of anxiety and behavior disorders before puberty, the average age at onset of major depression in early adolescence, and the average age at onset of substance use disorders in late adolescence or early adulthood

(1 –

4) . Furthermore, maternal depression has been associated with less robust response to treatment among depressed adolescent offspring

(5) . Until recently, little has been known about the effect of treatment for depressed mothers on their offspring

(6 –

8) . The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study provided a unique opportunity to investigate whether successful treatment for depressed women would lead to improvement in psychiatric disorders and symptoms among their offspring

(9) . The study of outcomes in these offspring is referred to as the child STAR*D (STAR*D-Child) study

(10,

11) . The main objective of the STAR*D study

(12 –

14) was to determine which treatment or sequence of treatments would be effective in adult patients with a diagnosis of major depression who did not remit after first-line treatment with the antidepressant citalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Remission was defined as a score of ≤7 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D

[15] ).

At the initiation of maternal treatment, approximately one-third of the offspring (aged 7–17 years) of women in the STAR*D study had a current psychiatric disorder

(10) . Eligible offspring were independently assessed in the STAR*D-Child study by a team that was not involved with the mothers’ treatment. Three months after the initiation of treatment for maternal depression, we reported that remission among the mothers was associated with a significant decrease in the rates of children’s diagnoses as well as decreases in internalizing, externalizing, and total symptoms

(11) . Interestingly, a ≥50% maternal response to treatment was required to detect improvement in the offspring.

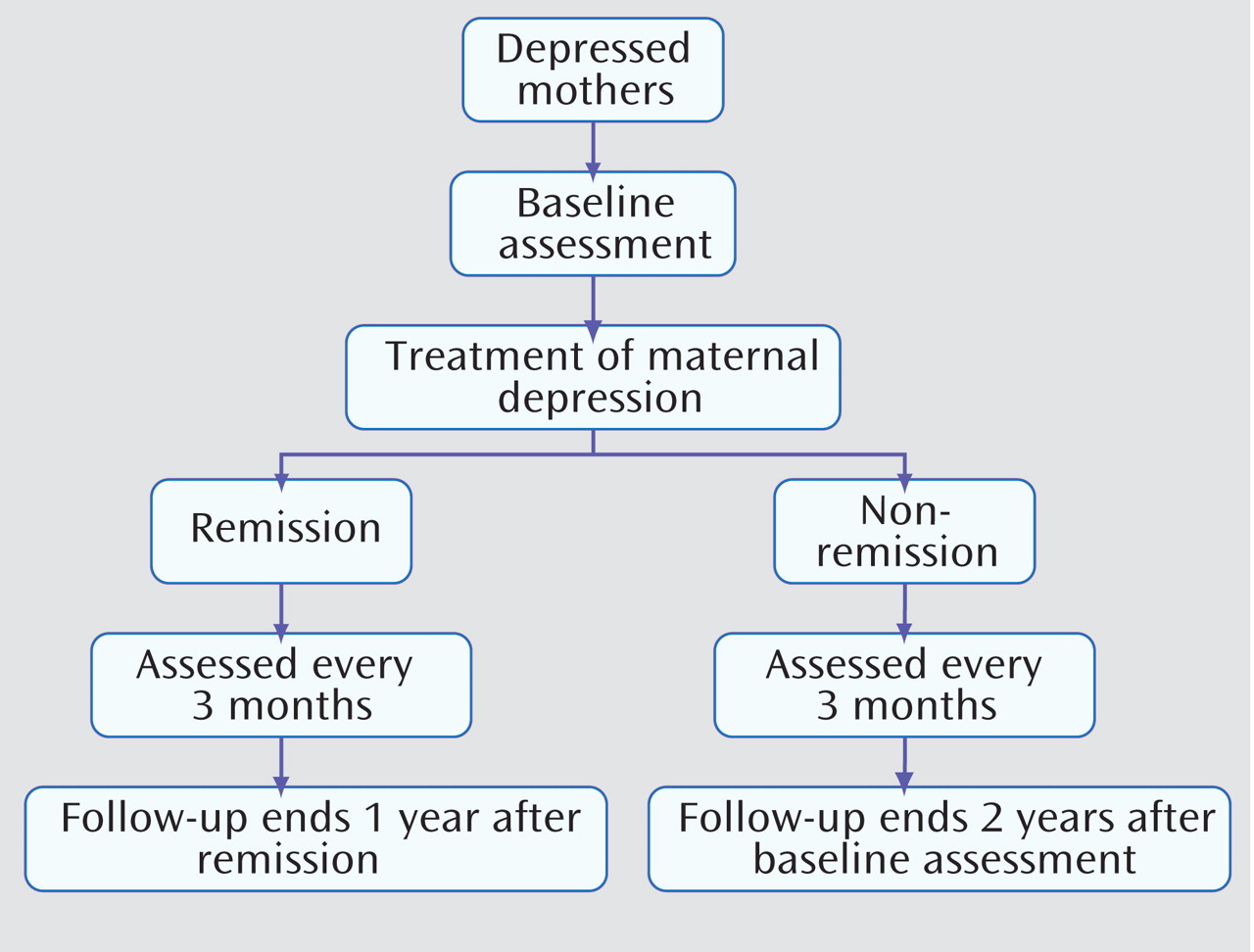

In the STAR*D-Child study, mothers and their offspring were followed every 3 months for 1 year after the initiation of treatment for maternal depression. The objective of the present study was to assess both maternal and child outcomes as reported in the STAR*D-Child study. We investigated two important issues that concern adult and child clinicians. First, we assessed whether those children of mothers who remitted by the 3-month follow-up remained well throughout the remainder of the 1-year follow-up interval. Second, we assessed whether those children of mothers who remitted after the 3-month follow-up similarly benefitted from maternal remission. In the present study, we refer to depressed mothers who remitted by the 3-month follow-up as early remitting subjects and to those who remitted after the 3-month follow-up as late remitting subjects. Most of the mothers (92%) who remitted by the 3-month follow-up were treated with citalopram

(11) . Late remitting subjects received two or more treatments as provided by the STAR*D protocol

(12) .

We hypothesized that the following outcomes would occur during the 1 year after the initiation of treatment for maternal depression: 1) mothers would show a significant decrease in HAM-D scores, with children showing a significant decrease in offspring psychiatric symptoms, and changes in child outcomes would be associated with changes in maternal HAM-D scores; 2) children of early remitting subjects, who were shown to benefit from remission of maternal depression 3 months after the initiation of treatment

(11), would continue to demonstrate a lower prevalence of psychiatric symptoms relative to children of nonremitting subjects, providing that their mothers remained in remission; and 3) children of late remitting subjects would demonstrate intermediate outcomes.

Results

Sample

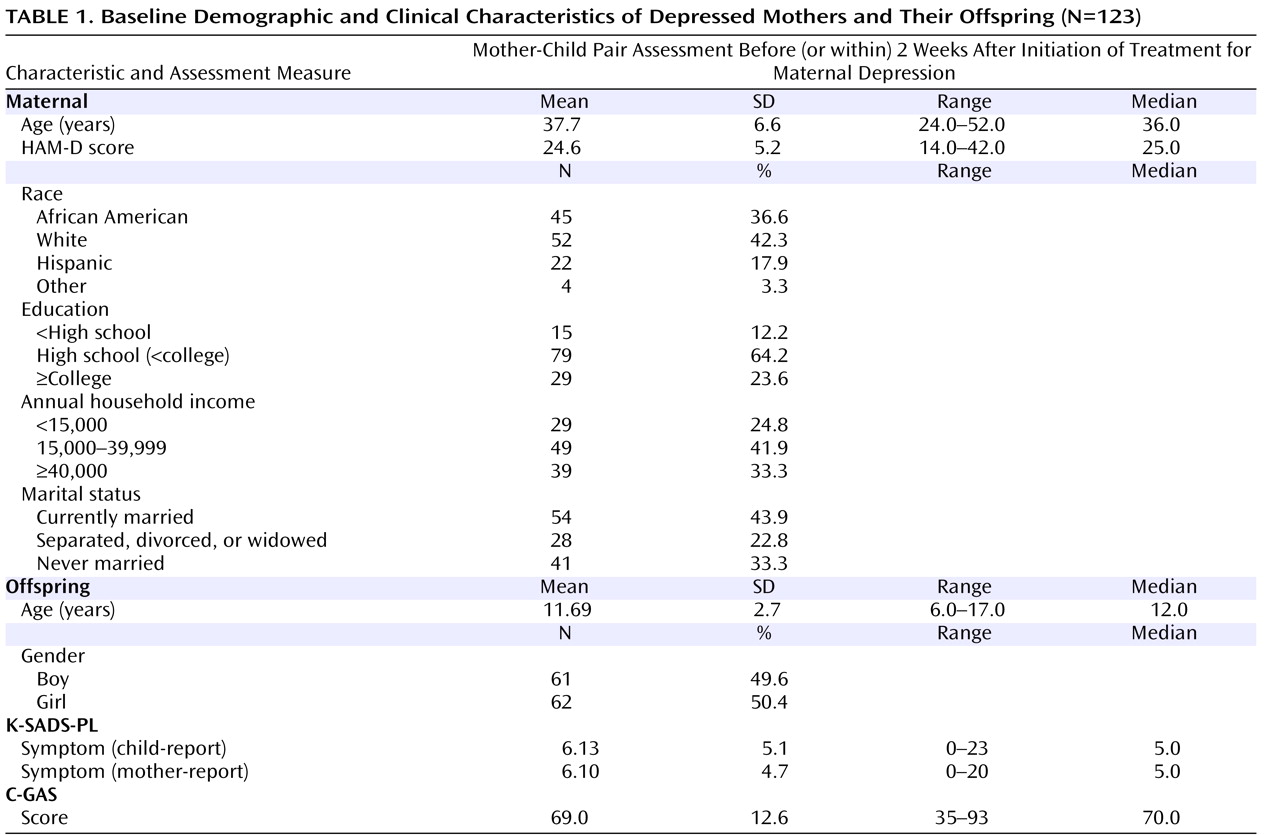

At baseline, 151 mother-child pairs were assessed. Of these, 123 completed at least one of four follow-up assessments. Unless noted otherwise, these 123 mother-child pairs constituted the evaluable sample in the present study, and their demographic characteristics are detailed in

Table 1 . Additional data pertaining to screening and recruitment have been reported elsewhere

(10,

11) . Baseline demographic characteristics of the 123 mother-child pairs with follow-up data and the 28 mother-child pairs who participated only in the baseline assessment did not differ on the following variables: education, household income, marital status, mothers’ baseline HAM-D scores, and child gender (data not shown). The 123 mothers with follow-up data were, on average, 3.3 years older than the 28 mothers without follow-up data (37.7 years old versus 34.4 years old; p=0.02). In addition, children with follow-up data were slightly older than children without follow-up data (11.7 years old versus 10.5 years old; p=0.05).

Changes in Maternal and Child Outcomes

Maternal depression severity

In the year following the initiation of treatment, 70 (57%) of the 123 mothers with follow-up data experienced remission (39 early remitting subjects and 31 late remitting subjects, respectively).

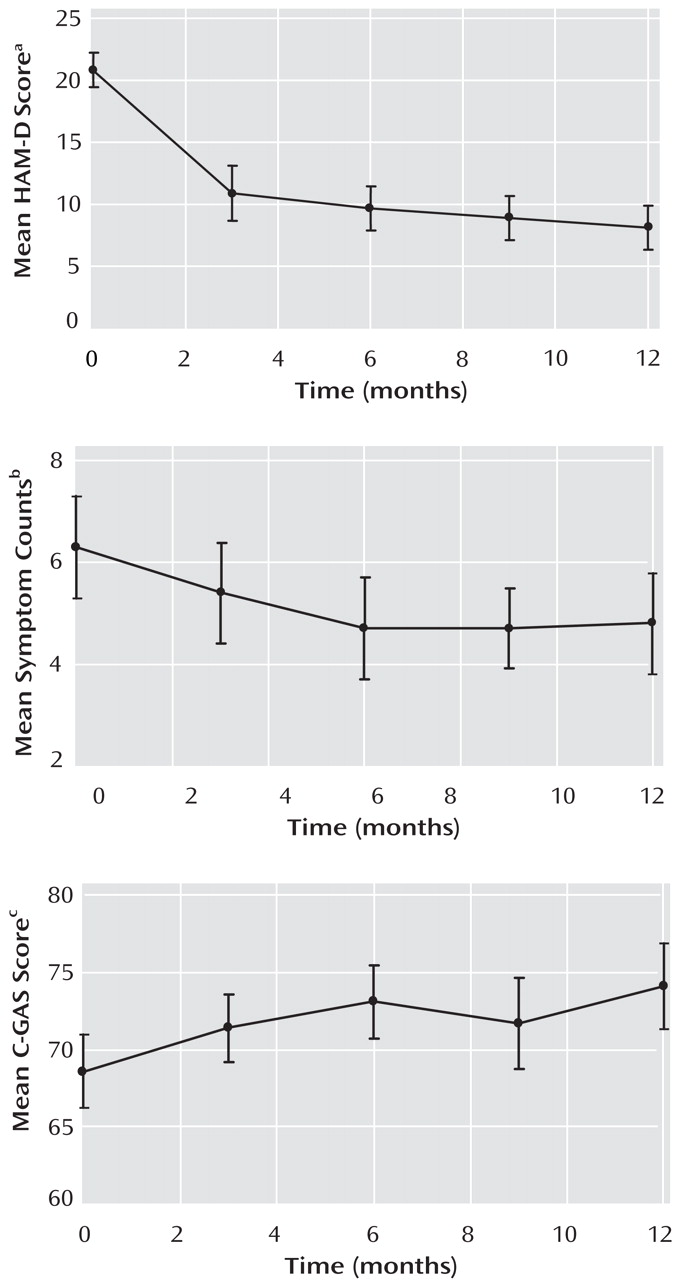

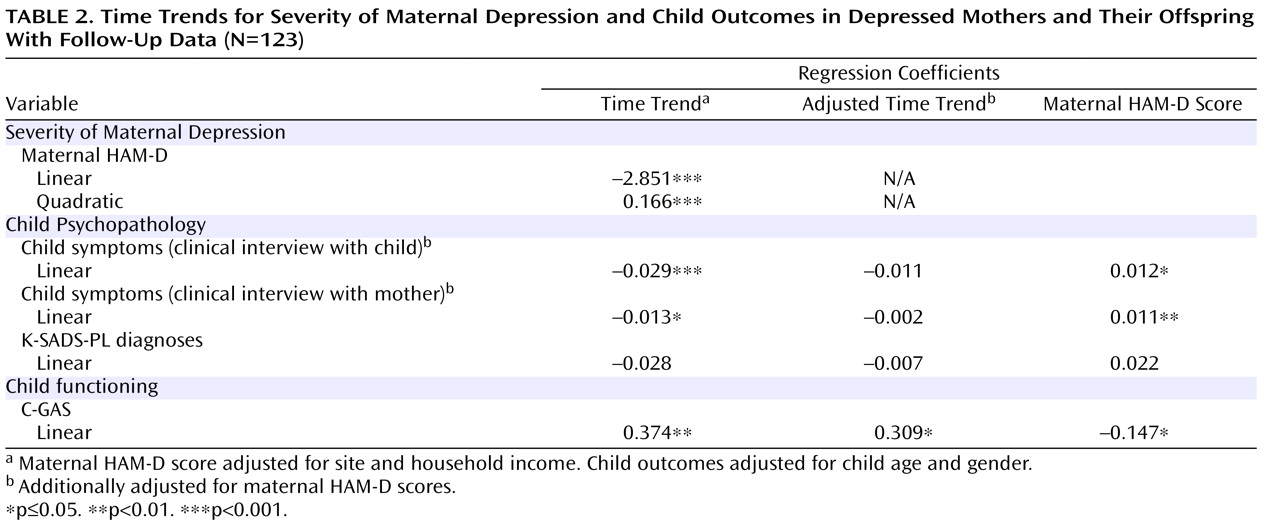

Figure 2 shows that maternal HAM-D scores decreased markedly during the first 3 months, moderately during the subsequent 3 months, and only slightly thereafter.

Table 2 shows the results of fitting a polynomial mixed-effects regression model, with linear and quadratic terms, to model changes in maternal depression severity. Both linear and quadratic terms were found to be significant. The negative linear component and the positive quadratic component suggest that maternal HAM-D scores decreased significantly and then leveled off and may have increased slightly toward the end of the follow-up interval. Coefficients for time trend refer to monthly changes in the relevant variable. Results of the random regression model show that there was significant variation in mothers’ baseline HAM-D scores (sigma

2 intercept =22.98, p=0.0002) and slope parameter (sigma

2 slope =1.665, p=0.03) but not in quadratic parameter. In addition, no significant correlation was found between mothers’ baseline values and rate of improvement (slope) in HAM-D scores during the 1-year follow-up period (correlation coefficient=–0.39, p=0.28).

Children’s psychopathology and functioning

Child symptoms decreased during the first 6 months, with few changes thereafter (

Figure 2 ). As shown in

Table 2, results of fitting a Poisson regression analysis reveal a significant negative linear term (–0.029 and –0.013 for the logarithm of children’s K-SADS-PL symptoms reported by the child and mother, respectively), which suggests that child symptoms decreased significantly over time during the year following the initiation of maternal treatment. Specifically, the expected number of symptoms decreased by 2.9% ([1–e

–0.029 ]×100) per month by child report and by 1.3% per month by maternal report. The proportion of children receiving one or more diagnoses (K-SADS-PL) also decreased over time, but the linear time trend was not statistically significant.

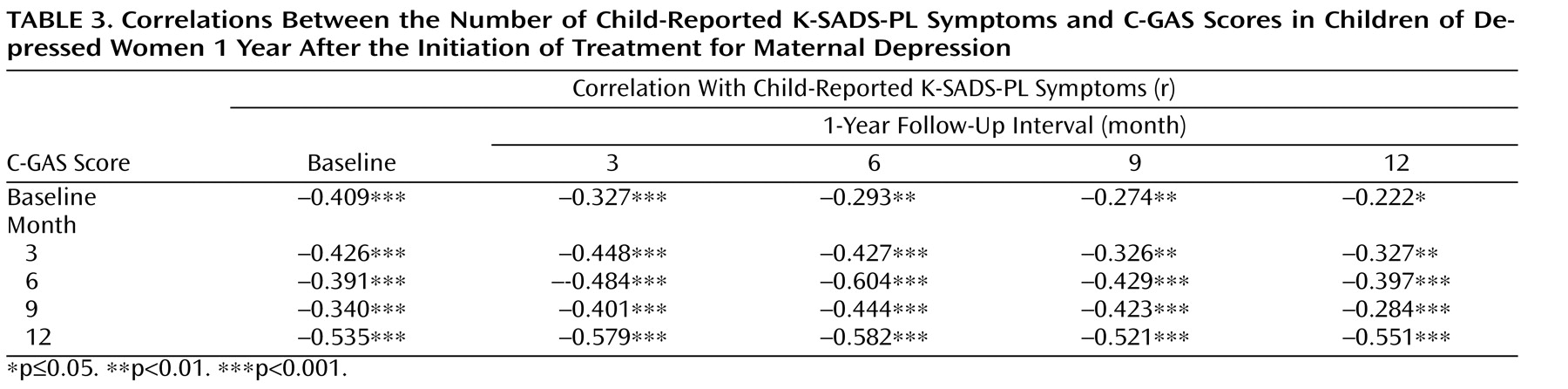

C-GAS scores improved (i.e., increased) moderately during the first 6 months, with few changes thereafter (

Figure 2 ). A random regression analysis showed that only the linear component was statistically significant, which suggests improvement in C-GAS scores over time (

Table 2 ). As expected, C-GAS scores had a moderate negative correlation with the number of K-SADS-PL symptoms (

Table 3 ). To arrive at the correlations shown in

Table 3, we used counts of child-reported symptoms from the screening section of the K-SADS-PL as well as C-GAS scores. Correlations between mother-reported child symptoms and C-GAS scores were similar to those detailed in

Table 3 (available upon request from the authors).

Associations Between Changes in Severity of Maternal Depression and Child Outcomes

To determine whether significant changes in child outcomes were related to changes in the severity of maternal depressive symptoms, we repeated the regression analyses but included mothers’ HAM-D scores as a time-dependent covariate. If the inclusion of maternal HAM-D scores decreased the magnitude of the coefficient associated with time while the regression coefficient associated with maternal HAM-D scores was found to be statistically significant, the results would suggest that changes in child outcomes were related to changes in maternal HAM-D scores. Applying these criteria, the results detailed in

Table 2 suggest that 1) changes in child symptoms (by maternal and child report) were related to changes in maternal depression severity as measured by HAM-D scores, and changes in maternal depression severity appeared to be associated with changes in child symptoms over time; and 2) although there was a significant association between child C-GAS scores and maternal HAM-D scores, this association explains very little of the linear change over time in C-GAS scores. Specifically, a one-unit decrease in maternal HAM-D scores was associated with a monthly 1.2% and 1.1% decrease in child- and mother-reported symptoms, respectively, and with a monthly increase of 0.147 in C-GAS scores.

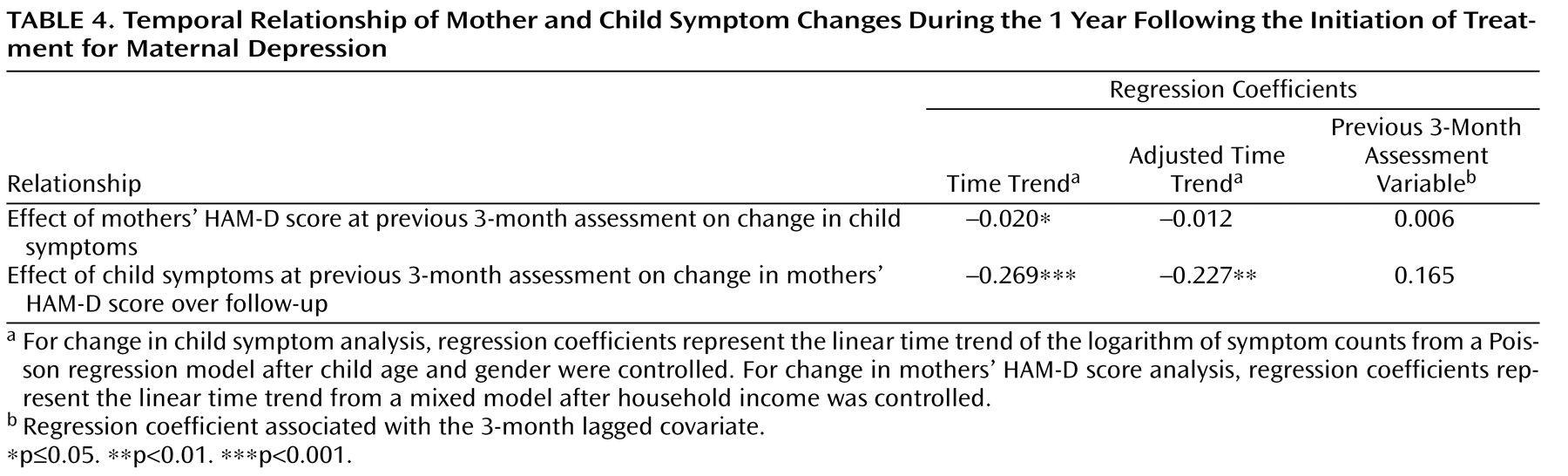

Temporal Relations Between Changes in Maternal and Child Symptoms

Through the use of time lag analysis, we examined whether changes in maternal HAM-D scores preceded changes in child symptoms. First, we estimated regression coefficients associated with time trends in child symptoms, from 3 to 12 months after baseline assessment, that were obtained using a Poisson regression model and for which child age, gender, and household income were controlled. Results of this analysis revealed that there was a statistically significant decrease in child symptoms during this time period (

Table 4 ). When maternal HAM-D scores from the previous 3-month assessments were included in the model as a time-dependent covariate, the time trend was no longer significant. However, the regression coefficient corresponding with the 3-month lagged covariate (maternal depression severity) was also not significant. These results suggest that changes in the mothers’ prior HAM-D scores (i.e., 3 months prior to the child assessment) may explain changes in child symptoms over time, although the lack of significant association with prior maternal HAM-D scores renders these results somewhat inconclusive.

We also examined the possibility that maternal HAM-D scores could be predicted by previously assessed child outcome measures

(26) .

Table 4 details the effects of child symptoms over the previous 3 months on changes in maternal HAM-D scores over the 3- to 12-month follow-up period. Although there was a significant decrease in maternal HAM-D scores over this period, the inclusion of child symptoms did not appear to explain this change (the adjusted time trend remained significant). Furthermore, there was no significant association between child symptoms over the previous 3 months and current maternal depression severity. These results suggest that decreases in maternal depression scores were not associated with decreases in child symptoms during the previous 3 months. Thus, it is unlikely that mothers became less depressed because their children improved (reverse causation).

Together, these results show that there was no statistically significant association between previous maternal HAM-D scores and current child symptoms or between previous child symptoms and current maternal HAM-D scores. Furthermore, the proportion of change in child symptoms that appeared to be related to change in maternal HAM-D scores was greater (approximately 47%) than the proportion of change in maternal HAM-D scores that appeared to be related to change in child symptoms (approximately 18%).

Child Outcomes According to Maternal Remission Status

Before analyzing child outcomes by maternal remission status, we compared baseline characteristics for early, late, and nonremitting mothers. Nonremitting mothers were significantly less likely to have an annual household income ≥$40,000 (p=0.005) and less likely to be currently married or cohabitating (p=0.04). These mothers were more likely to have higher HAM-D scores at baseline (p<0.0001). Specifically, at baseline the mean HAM-D scores for early, late, and nonremitting mothers were as follows: 22.26 (SD=4.31), 23.97 (SD=5.06), and 26.98 (SD=5.14), respectively.

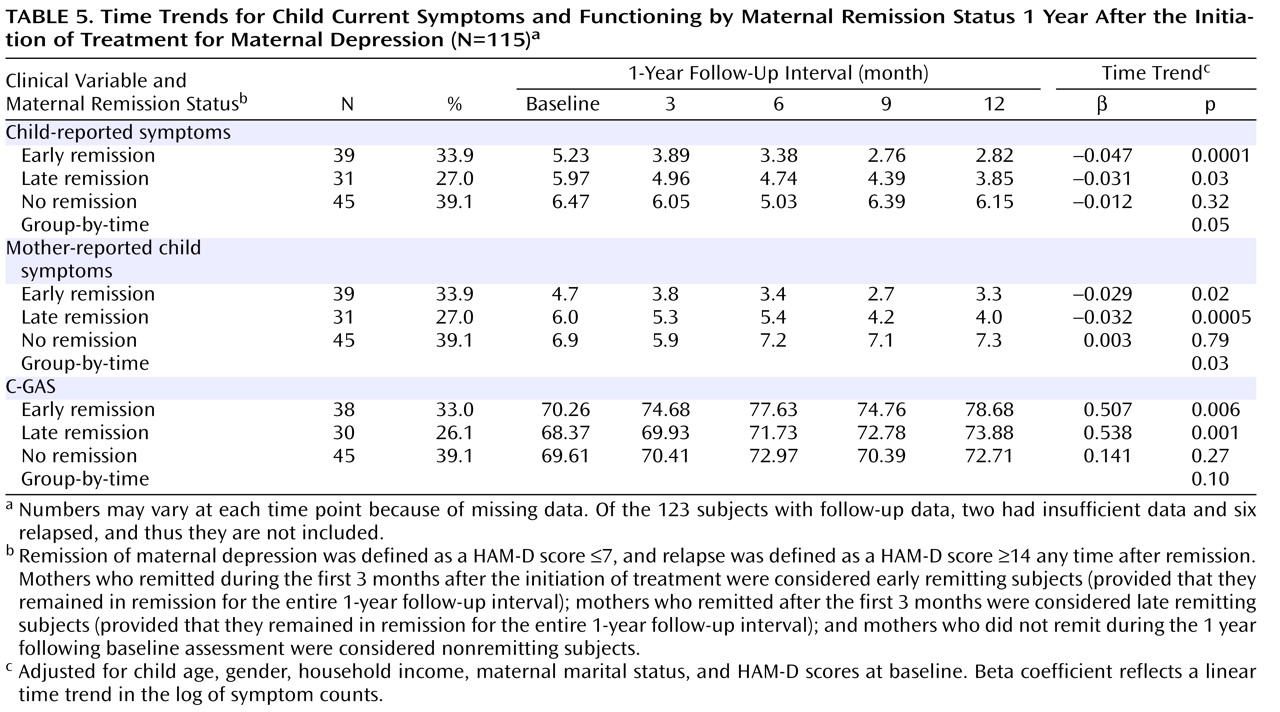

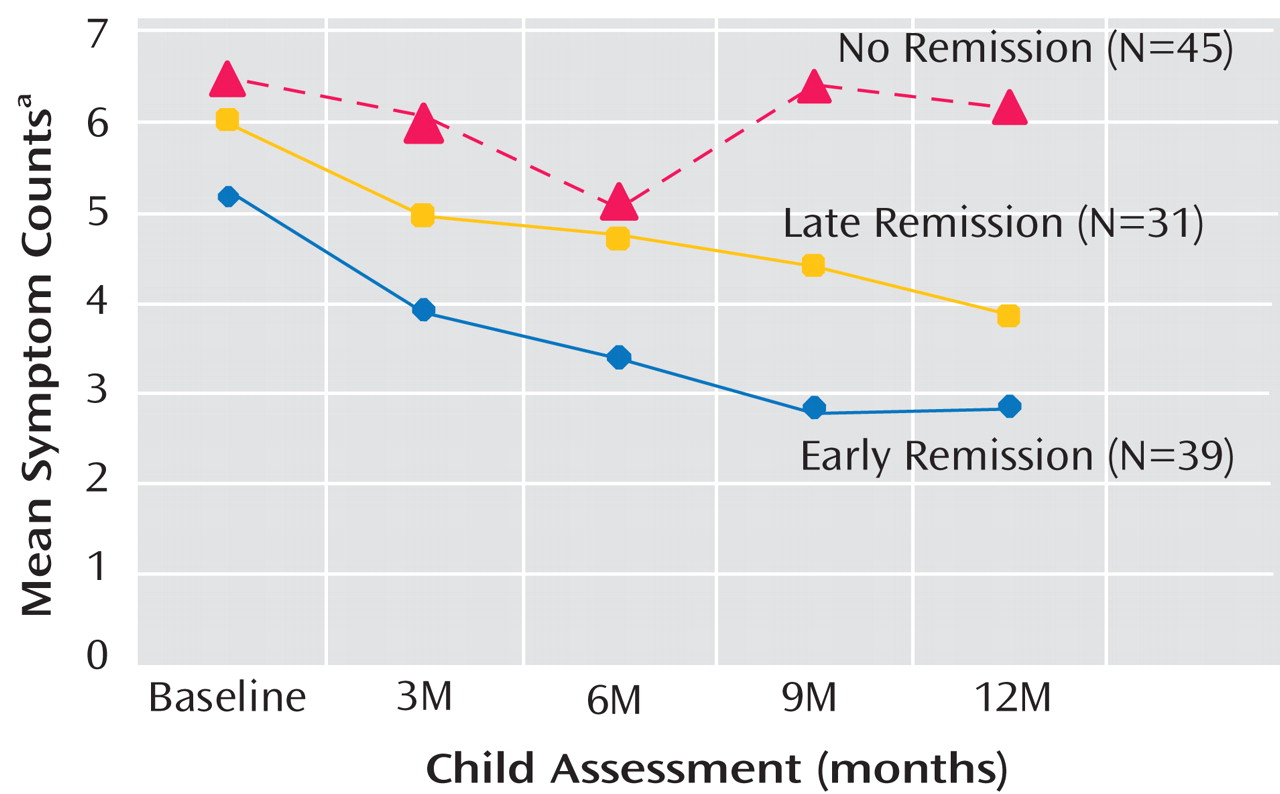

As shown in

Table 5, we compared child outcomes (symptoms and C-GAS scores) by time of maternal depression remission (early, late, and nonremitting mothers), adjusting for child age, gender, and household income and mothers’ baseline HAM-D scores. Because estimates for the six mothers who relapsed would have been unreliable, they were not included in the analysis for child outcomes according to maternal remission status. Two additional mothers had insufficient data. Thus, this particular analysis was based on 115 mother-child pairs. During the 1-year follow-up interval, there was a statistically significant decrease over time in the number of symptoms among children of early and late remitting mothers, as reflected in the beta coefficients detailed in

Table 5 . In contrast, among children of nonremitting mothers, the number of child-reported symptoms increased and did not change significantly by the end of the 1-year follow-up interval (

Figure 3 ). The group-by-time interaction coefficients were significant (p=0.05 and p=0.03 for child- and mother-reported symptoms, respectively), which suggests that changes in the pattern of symptoms differed significantly over time across the three mother-child pair groups. C-GAS scores increased significantly over time among children of early (p=0.006) and late (p=0.001) remitting mothers, but the group-by-time interaction was not statistically significant.

The results shown in

Table 5 include all 115 children, with and without symptoms at baseline. In addition, we conducted an exploratory analysis of symptoms among 66 children who had definite K-SADS-PL symptoms at baseline. The mean number of definite symptoms among these children during each 3-month assessment period was as follows: baseline, 10.1 (SD=10.1); 3 months, 7.8 (SD=10.0); 6 months, 8.6 (SD=11.1); 9 months, 9.4 (SD=11.2); and 12 months, 8.3 (SD=11.5). After excluding the six mother-child pairs corresponding to the six relapsing mothers, we conducted an exploratory analysis of time trends limited to children with definite baseline symptoms (N=60 [

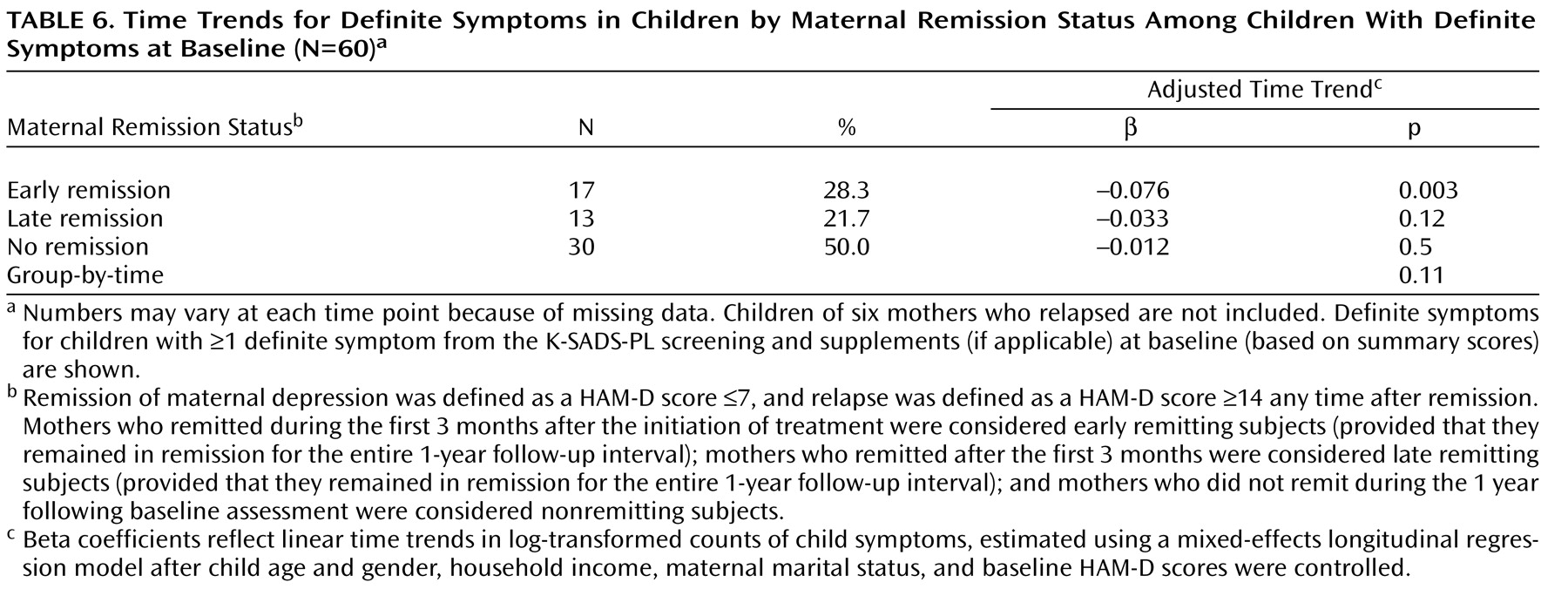

Table 6 ]). As shown in

Table 6, time trends were significant only for children of early remitting mothers, but the direction of the results was similar to the analyses that included all children (

Table 5 ).

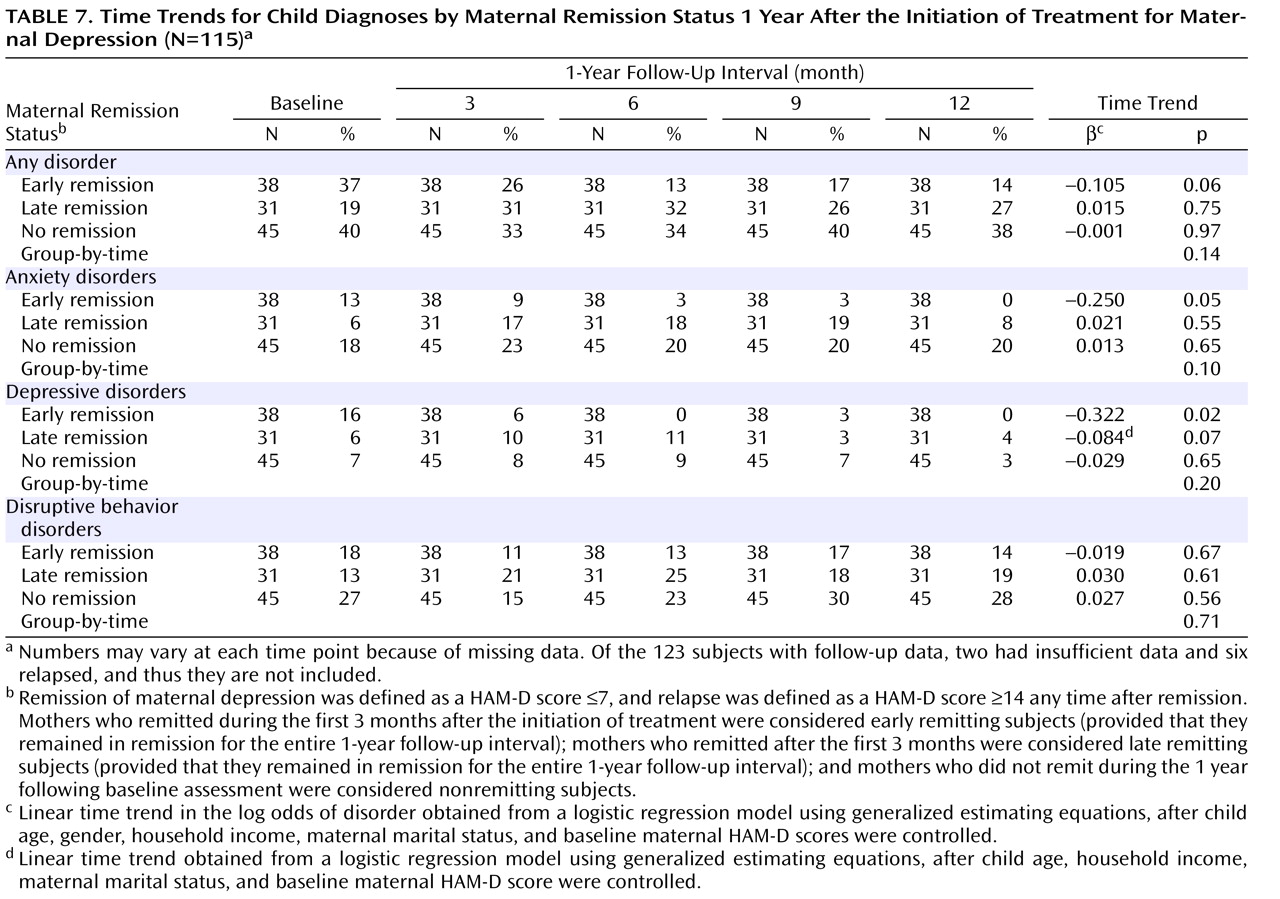

Additionally, we examined the prevalence of child psychiatric disorders by maternal remission status (

Table 7 ). Prevalence of anxiety and depressive disorders decreased significantly over time among children of early remitting mothers, with little change among children of nonremitting mothers and intermediate outcomes among children of late remitting mothers. The prevalence of disruptive behavior disorders did not change significantly, regardless of maternal depression status.

Children Receiving Treatment

Children did not receive treatment as part of the STAR*D-Child study. However, if a child had a diagnosis (K-SADS-PL) and was impaired or distressed, the interviewer offered feedback to the child and the child’s family, encouraged treatment, and provided appropriate referrals. At each follow-up assessment, mothers were asked the following question: “Has your child received treatment for a psychiatric condition or emotional problem since we last saw you?” There were no statistically significant differences in the proportion of children receiving treatment by maternal remission status, with 15%, 16%, and 22% of children of early, late, and nonremitting mothers, respectively, receiving treatment. The number and proportion of children receiving treatment among those in need of treatment (defined as a K-SADS-PL diagnosis and C-GAS score <70) were as follows: 7 (26.9%), 6 (28.6%), 7 (36.8%), and 8 (50%) at the 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month follow-up assessments, respectively.

Discussion

In the present analysis, mothers with major depressive disorder were treated, and their offspring were followed up for 1 year after the initiation of maternal treatment. At the beginning of the study, approximately one-third of the children (aged 7–17 years) had a current psychiatric disorder, and approximately one-half had a lifetime history of a psychiatric disorder

(10) . At the 3-month follow-up assessment, we found that maternal remission from depression was associated with a significant decrease in children’s diagnoses

(11) . One year after the initiation of treatment for maternal depression, we found that maternal depression severity and children’s psychiatric symptoms continued to decrease over time, with most of the offspring symptom alleviation and functional improvement occurring within the first 3 to 6 months during the 1-year follow-up interval. Furthermore, decreases in the number of child psychiatric symptoms were significantly associated with decreases in maternal depression severity as reflected in maternal HAM-D scores, and these decreases tended to precede symptom and functional improvements in children. When child outcomes were examined separately for the offspring of mothers who remitted early (i.e., within the first 3 months after the initiation of treatment for maternal depression), later (i.e., after the first 3 months of the initiation of treatment for maternal depression), or not at all over the 1-year follow-up interval, a statistically significant decrease in symptoms was evident in children of early and late remitting mothers but not in children of nonremitting mothers. We also found that child global functioning improved significantly over time. In contrast, offspring functioning remained unchanged at the 3-month follow-up assessment

(11) . This pattern is consistent with previous research indicating that reductions in psychiatric symptoms frequently precede changes in functioning

(27,

28) . We do not know why maternal depression remission had a positive impact on children, but mechanisms suggested by other investigators include diminished marital discord, improved parenting, and a less critical attitude toward the offspring

(25) .

One-third of the children had a current psychiatric disorder at baseline

(10) . However, when symptom scores were averaged across the entire sample, it might have appeared that children were not severely impaired at baseline and that our results may only be applicable in mildly to moderately impaired children. An exploratory analysis restricted to children with at least one definite symptom at baseline revealed that symptoms decreased significantly over time only among children of early remitting mothers. However, the direction of change over time was the same as it was in the analysis for the entire sample (i.e., a greater decrease of symptoms among children of early remitting mothers relative to children of late remitting mothers and no significant change in children of nonremitting mothers).

An exploratory analysis of psychiatric diagnoses suggests that among children of early remitting mothers the prevalence of internalizing disorders (i.e., depressive and anxiety disorders) decreased significantly over time, without similar decreases among children of nonremitting mothers and intermediate outcomes among children of late remitting mothers. However, the prevalence of disruptive behavior disorders did not change significantly in any of the three mother-child pair groups. We do not know why a remission of maternal depression was not associated with changes in the prevalence of these disorders. However, in their study of the offspring of depressed parents, Hammen and Brennan

(29) found that severity of maternal depression was less likely to be associated with nondepressive child outcomes than chronicity. Additionally, the category (disruptive behavior disorders) includes attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, a disorder that might not change significantly when the rearing environment changes (i.e., when maternal depression remits).

In the STAR*D study, an estimated one-third (36.8%) of the patients experienced remission with one treatment (citalopram) in approximately 3 months. The cumulative remission rate (which is a theoretical rate because it assumes that there were no dropouts) was 67% after completion of all four treatment levels, which occurred within a 1-year interval

(13) . The STAR*D study revealed that persistent treatment of adult depression can lead to more remissions over time, and the STAR*D-Child study showed that children’s psychiatric symptoms decrease when mothers experience remission. In the STAR*D-Child study, the benefit for children was greater when mothers remitted early. However, children of late remitting mothers also experienced a statistically significant decrease in psychiatric symptoms.

Except for a small pilot study (N=18) that we conducted several years ago

(6), there are no other published studies, to our knowledge, that have followed the outcomes of children of depressed parents based on parental remission status after treatment of parental depression. Beardslee et al.

(8) examined parents with mood disorders (N=93) and their children (N=121), who were randomly assigned to a psycho-educational intervention or control condition. Treatment of parental mood disorders was not provided as part of the study, and the analysis did not relate changes in parental clinical status to changes in child clinical outcomes. However, in both the intervention and control conditions, children reported increased understanding of parental illness, and internalizing symptoms decreased among the children.

In our study sample, remission was not evenly distributed. As expected, nonremitting mothers had higher HAM-D scores at baseline. Additionally, these mothers were more likely to have lower annual incomes and more likely to be single relative to mothers who experienced remission. The STAR*D study reported that patients who were married or cohabitating remitted with greater frequency than single participants. This suggests that social support may be a positive predictor of response to treatment for major depressive disorder

(9) .

Mothers might have become less depressed in reaction to positive changes experienced by their children (reverse causation). To address this possibility, we examined whether previous maternal HAM-D scores predicted subsequent child symptoms as well as whether previous child symptoms predicted subsequent maternal HAM-D scores. There was no significant association between previous maternal HAM-D scores and subsequent child symptoms or between previous child symptoms and subsequent maternal HAM-D scores. However, although a moderately large proportion (approximately 47%) of the changes in child symptom scores over time appeared to be related to changes in maternal HAM-D scores, the changes in maternal HAM-D scores, which appeared to be the result of changes in child symptom scores, were more modest (18%). These findings suggest that reductions in child symptoms are not likely to be the predominant reason for the observed decrease in maternal HAM-D scores.

There are several limitations to the present study. First, child assessors were aware that all mothers were depressed at baseline. However, they were not involved with the mothers’ treatment and were unaware of the mothers’ response to treatment.

Second, although our study did not provide treatment to children, some child participants received treatment outside of the study. Since treatment was not significantly more prevalent in the offspring of nonremitting mothers than in the offspring of mothers who experienced remission, child treatment is not likely to have biased our results. Last, limited statistical power rendered our findings pertaining to changes in the number of children with psychiatric disorders to be tentative and precluded an examination of changes in the prevalence of specific disorders.

Clinical Implications

The STAR*D study showed that continued efforts to treat depression until remission is achieved are likely to benefit adults with nonpsychotic major depressive disorder. The present study revealed that continued treatment of maternal depression until remission is achieved is associated with decreased symptoms and improved functioning in the offspring. Clinicians who treat adult patients might choose to inform depressed mothers about the potential benefits of remission for their children. Child clinicians may consider recommending treatment for maternal depression as an adjunct to child treatment when children of depressed mothers seek treatment. Future research should examine the mechanisms underlying the link between remission of maternal depression and changes in child outcomes and whether remission of paternal depression might be associated with similar outcomes.