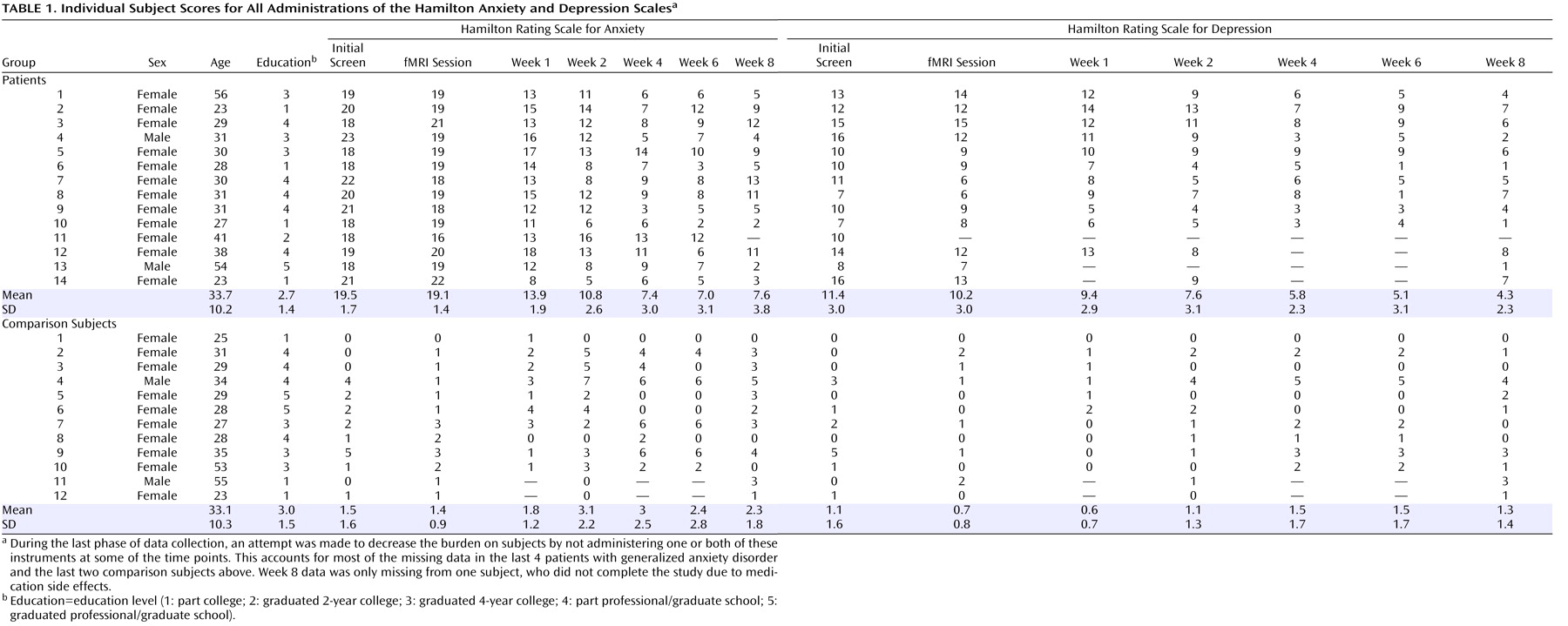

Generalized anxiety disorder affects 5.7% of the English-speaking population in the United States

(1) and can have dramatic effects on one’s social relations, occupational functioning, and well-being. Worry is a cardinal feature of generalized anxiety disorder and is often observed in other anxiety and mood disorders, which may in part explain the high rates of other illnesses that are comorbid with generalized anxiety disorder

(2) . Despite the high prevalence and frequent comorbidity of generalized anxiety disorder and the suffering it causes, its pathophysiology has been relatively understudied in comparison to other anxiety disorders

(3,

4) .

A theoretically sound starting place for investigating the pathophysiology of generalized anxiety disorder is to focus on worry and the anticipation of negative outcomes

(4 –

8) . Research on the neural circuitry of the anticipation of aversive stimuli has implicated a number of brain regions, including the amygdala, insula, anterior cingulate cortex, and prefrontal cortex

(8 –

14) . To facilitate work in this area, we developed a paradigm for investigating brain activity associated with the anticipation of aversive pictures

(8,

14,

15) . The paradigm involves one warning cue (e.g., a minus sign) that is followed by aversive pictures and a second warning cue (e.g., a circle) that is followed by neutral pictures. Subjects are instructed about the cue-picture pairings at the outset of the experiment. Anticipatory responses in this paradigm have been characterized in nonpsychiatric populations using both eye-blink startle

(15) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)

(8,

14) .

We hypothesized that patients with generalized anxiety disorder would show abnormalities in the circuitry normatively activated by the anticipation of aversion

(8,

10,

16), particularly in the amygdala

(8,

11,

14,

17 –

19) . Findings for amygdala function in generalized anxiety disorder have been mixed

(20 –

23), but no study with patients with generalized anxiety disorder has disentangled stimulus anticipation and stimulus response processes

(8,

14) . Based on the research reviewed above and related cognitive findings

(4), this study was designed to test the prediction that amygdala activation in anticipation of aversive pictures would be greater in patients with generalized anxiety disorder than nonpsychiatric comparison subjects, whereas no group differences were expected in anticipation of neutral pictures. Theoretical and empirical work implicating hyperresponsivity to both unpleasant and neutral stimuli in patients with generalized anxiety disorder

(7,

21,

24) suggested the testable alternative hypothesis that patients with generalized anxiety disorder would show greater anticipatory amygdala activation than comparison subjects preceding both aversive and neutral pictures. Group differences were also examined in other brain regions implicated in the anticipation of aversion

(8,

10,

12,

14,

16,

25) . Finally, based on prior reports of anterior cingulate cortex activity predicting treatment response

(26 –

29), we tested whether pretreatment anticipatory activity in the anterior cingulate cortex was associated with outcome following an 8-week trial of venlafaxine.

Discussion

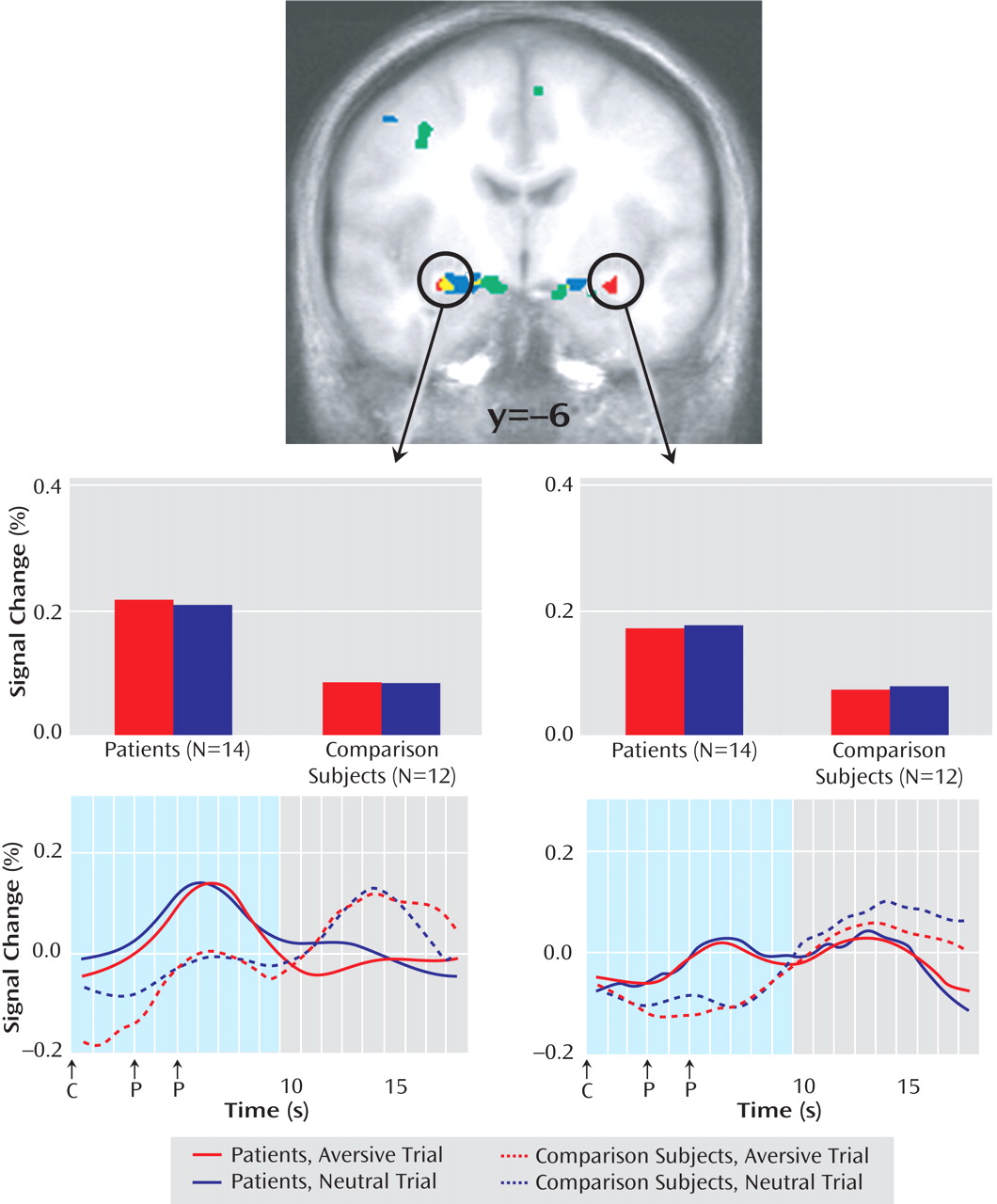

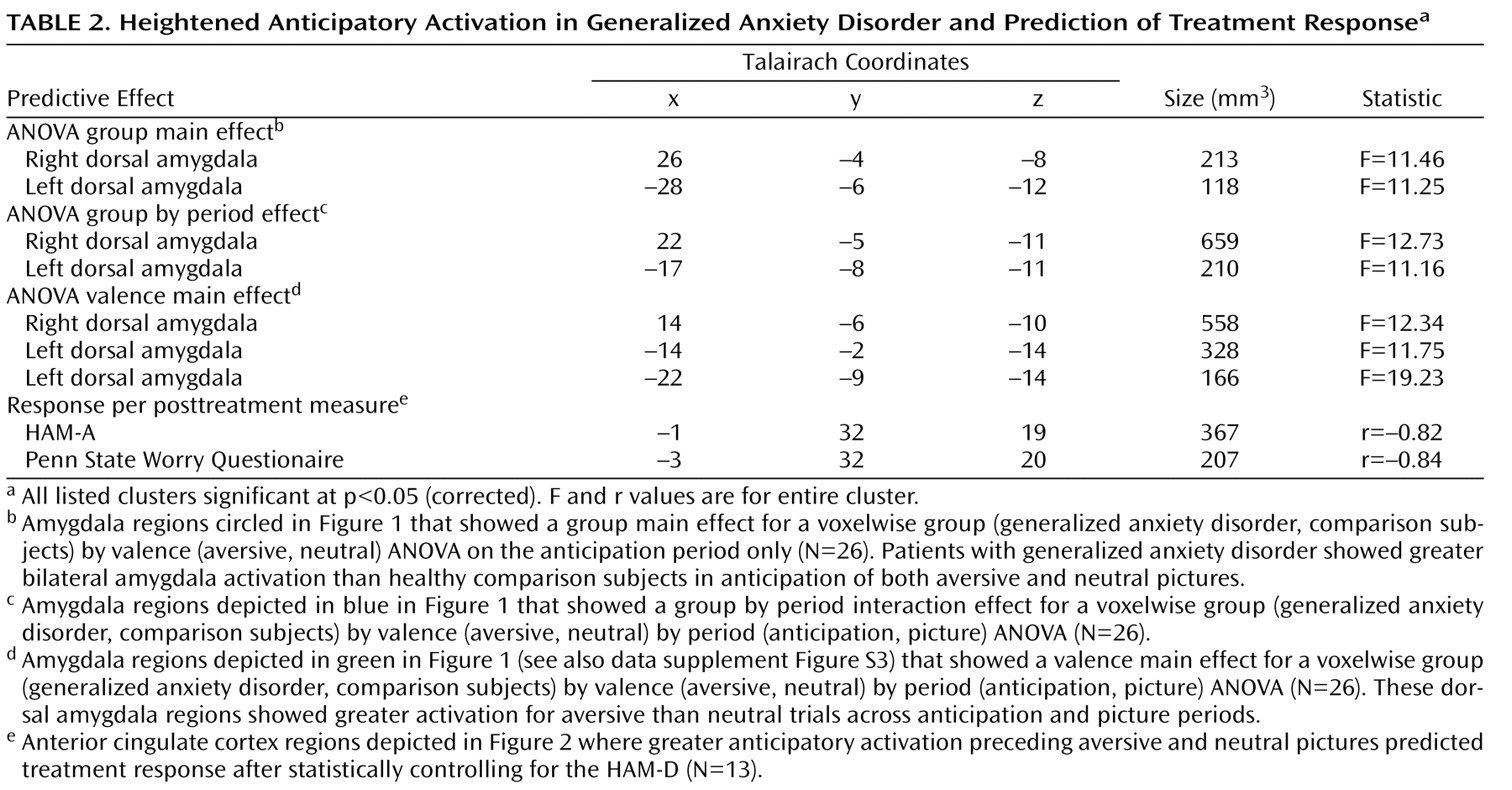

Anticipatory amygdala responses differentiated patients with generalized anxiety disorder and healthy comparison subjects. Specifically, the subjects with generalized anxiety disorder showed greater anticipatory activity in the bilateral dorsal amygdala preceding both aversive and neutral pictures than did the comparison subjects. These group differences for the right amygdala during anticipation were not present during picture viewing. This increased and indiscriminate response to anticipatory signals in the amygdala of subjects with generalized anxiety disorder may reflect a pathophysiological mechanism associated with the anticipatory anxiety and worry that are cardinal features of the disorder. In addition, anticipatory anterior cingulate cortex activity prior to the start of treatment was associated with response to venlafaxine.

Preclinical and clinical research has consistently shown that the amygdala preferentially responds to aversion across a variety of paradigms

(8,

11,

14,

17 –

19) . We did not find support for the hypothesis that amygdala activity in patients with generalized anxiety disorder was exclusively heightened in anticipation of aversion. Instead, subjects with generalized anxiety disorder showed anticipatory hyperresponsivity preceding both aversive and neutral pictures in amygdala regions lateral to the dorsal amygdala areas that respond preferentially to aversion (

Figure 1 )

(8,

14) . These findings lend neurobiological support to the conclusion drawn by Hoehn-Saric et al.

(21) that “GAD patients overreact to both pathology-specific and non-specific cues.” The mere onset of

any anticipatory cue presented in the context of cues that signal aversion may result in an initial indiscriminate amygdala response that alerts the GAD patient to the possibility of a negative outcome. Future research could address whether this putative pathophysiological mechanism in generalized anxiety disorder also extends to positive stimuli.

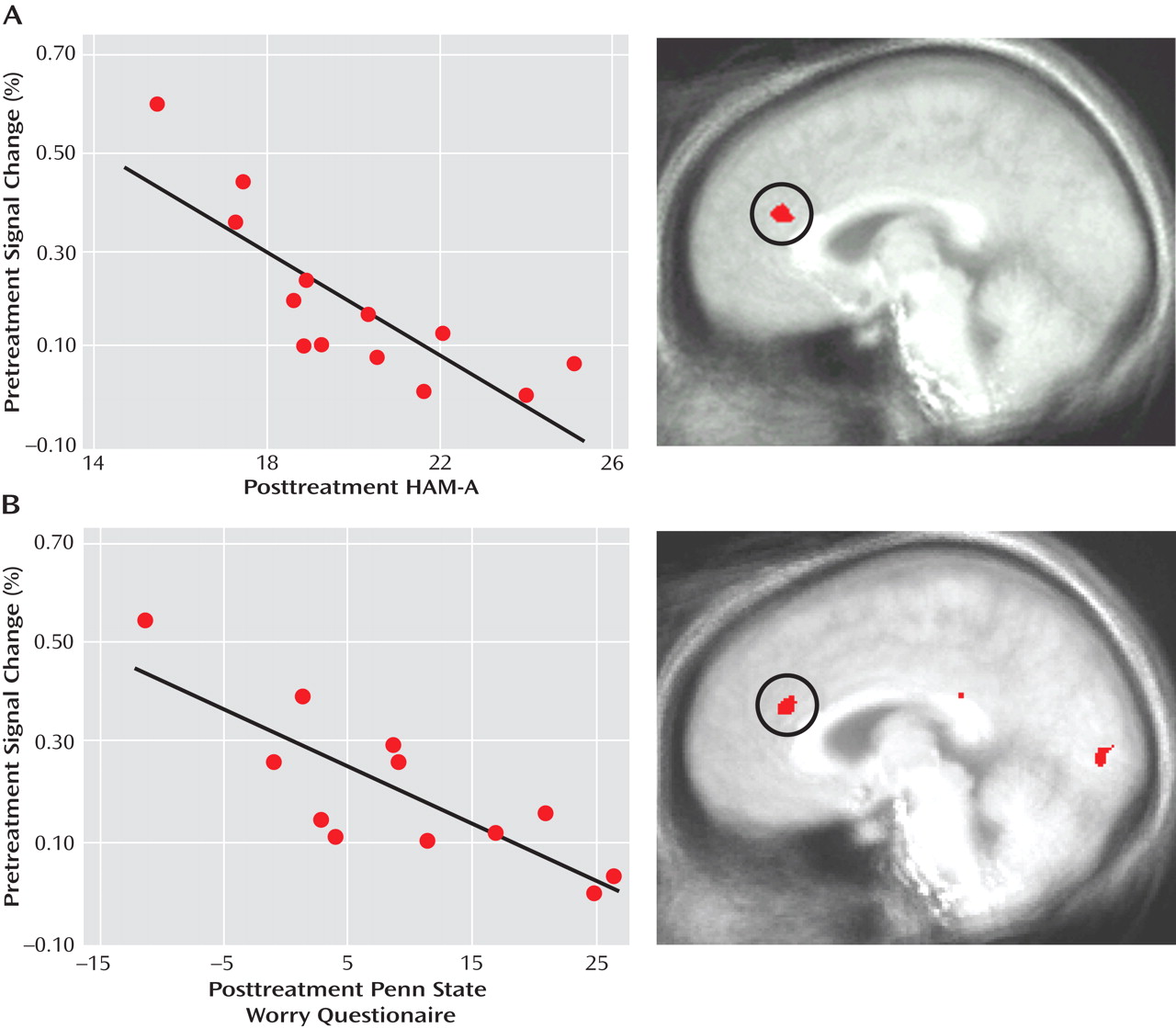

Patients with generalized anxiety disorder with increased anticipatory activity in the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex had better responses to venlafaxine 8 weeks later. Based on evidence pointing to the importance of the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex for detecting conflict in the emotional domain and recruiting cognitive control processes to resolve the conflict

(37,

38), we believe that heightened activity in the anterior cingulate cortex is indicative of preserved top-down regulation and volition in patients with better outcomes

(27,

28,

38) . This finding is consistent with multiple other reports of pretreatment activity in the anterior cingulate cortex predicting better clinical outcome in depressed patients

(26 –

29) . Our previous report on generalized anxiety disorder

(29) found that larger pretreatment anterior cingulate cortex responses to facial expressions were associated with better clinical outcome in a region that overlaps with the anterior cingulate cortex areas shown in

Figure 2 . With 10 of the same patients participating in both studies (see Method), this marks the first time that the association between pretreatment anterior cingular cortex activity and treatment response has been demonstrated using different paradigms in the same subjects. The similar findings for generalized anxiety disorder and depression suggest commonalities in the neural predictors of treatment response. Further research is needed to determine the extent to which the relation between treatment response and anterior cingulate cortex activity is shared with other anxiety disorders, as has been found for other sources of overlap between generalized anxiety disorder and depression

(39,

40) .

The present study further adds to this literature by demonstrating that

anticipatory brain processes are associated with treatment response. This association was found for both a general measure of anxiety (HAM-A) and a specific measure of worry (the Penn State Worry Questionnaire), but only after control was added for depression as measured by the HAM-D. Indeed, the analytic tools employed to statistically account for co-occurring depression symptoms represent a methodological contribution to this literature

(35) . Our findings suggest that research on neural predictors of treatment response will benefit from efforts to carefully address co-occurring depression and anxiety symptoms in sample recruitment and statistical testing. Moreover, the anterior cingulate cortex association with posttreatment HAM-A remained even after control was added for the Penn State Worry Questionnaire, and the anterior cingulate cortex association with posttreatment Penn State Worry Questionnaire remained even after control was added for the HAM-A, suggesting that anticipatory anterior cingulate cortex activity is independently associated with decreases in worry and other anxiety symptoms. Finally, the pregenual anterior cortex area found here and in previous studies

(28,

29) is dorsal to the area implicated in other works

(26,

27) . Anatomic specificity deserves attention in future research investigating the anterior cingulate cortex in treatment response, especially in light of recently reported cytoarchitecture data for pregenual anterior cingulate cortex

(36) .

In contrast to the amygdala findings, group differences were not observed for other key brain areas activated by our anticipation paradigm in healthy volunteers in this study (data supplement Tables 2 and 3) and previously

(8,

14) . In a recent report, “anxiety-prone” subjects (nine of 13 met DSM-IV criteria for generalized anxiety disorder) showed greater insula responses than “anxiety-normative” subjects (no DSM-IV disorders) during the anticipation of snake and spider pictures

(25) . The differences in sample and stimuli may explain why we found no group differences anywhere in the insula at p<0.05 corrected (or at p<0.005 uncorrected) for the voxelwise analyses or for analyses using the anterior insula regions previously identified with this anticipation paradigm (data supplement Table 2)

(8) . To address concerns about type II error, larger samples are needed to further assess group effects. Another limitation is the absence of online behavioral or autonomic data for examining relations with the neural findings. Of relevance, however, are the associations of brain data with treatment response, a valid and important behavioral criterion.

Using a paradigm that capitalized on anticipatory abnormalities as a key feature of anxiety disorders, we found that anticipatory amygdala hypersensitivity in a lateral region of the dorsal amygdala is a pathological signature of generalized anxiety disorder, whereas greater anticipatory activity in the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex may have adaptive benefits. This association of anterior cingulate cortex activity with treatment response to venlafaxine builds on prior reports indicating promise for neuroimaging as a prognostic tool

(26 –

29) . Crossover studies and double-blind designs involving placebo controls are important next steps for extending the findings from this initial open-label study that implicated amygdala-based anticipatory processes in the pathophysiology of generalized anxiety disorder and anterior cingulate cortex-based anticipatory processes in treatment response.