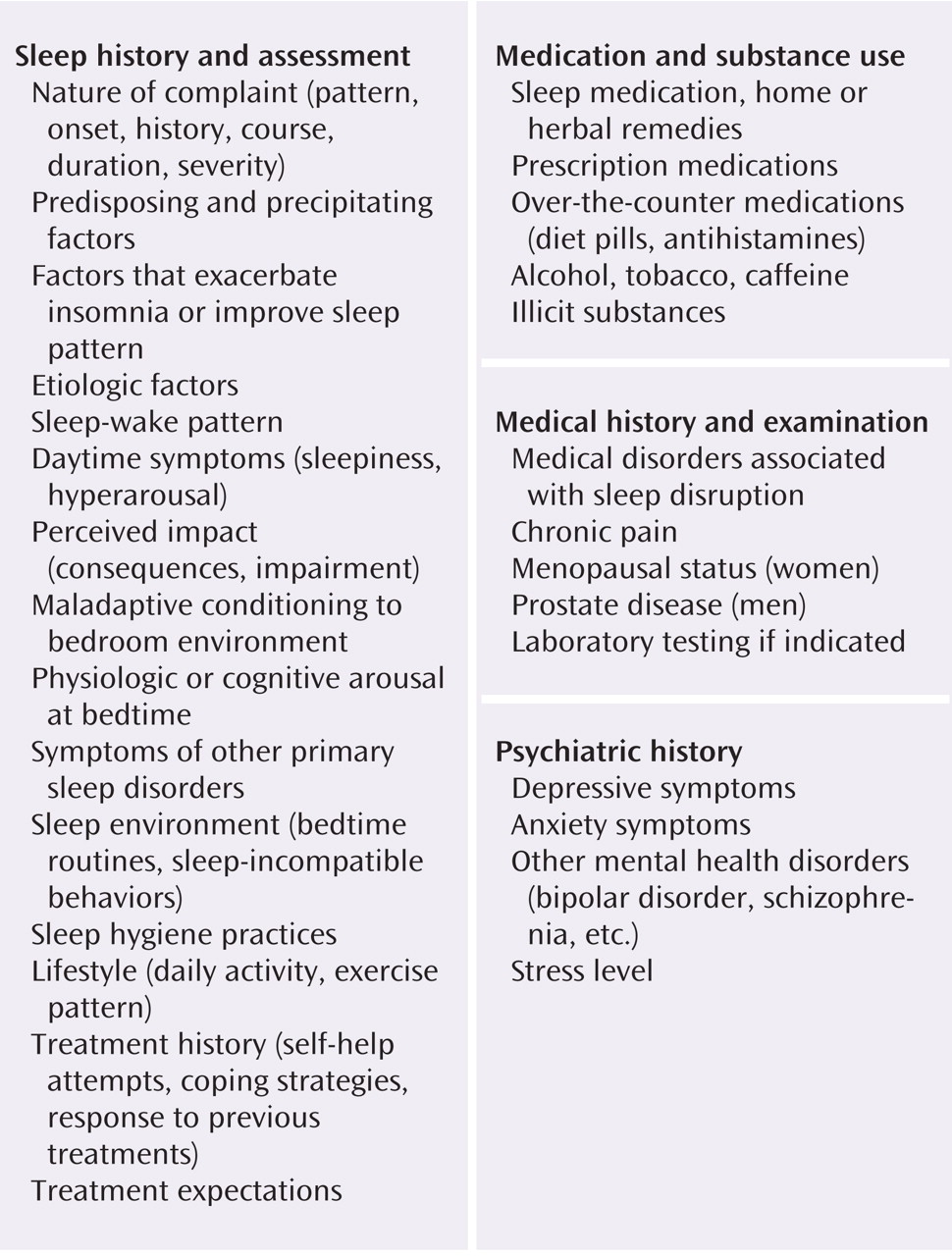

Insomnia symptoms, which include difficulty falling asleep, multiple or prolonged awakenings from sleep, inadequate sleep quality, or short overall sleep duration when given enough time for sleep, are common across the spectrum of psychiatric illness, including bipolar disorder. When these symptoms cause impairment, it becomes important to address them; insomnia has been independently associated with significant morbidity, functional impairment, and health care costs

(113) . The multitude of treatments for insomnia can be broadly grouped into psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic treatments. We discuss each in the context of bipolar disorder.

Psychotherapy for Bipolar Insomnia

The primary psychotherapeutic treatment of insomnia is cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I). The efficacy of CBT-I in primary insomnia (insomnia not related to another medical or psychiatric disorder) is well established, and there is some suggestion that it may be more effective than pharmacotherapy

(114,

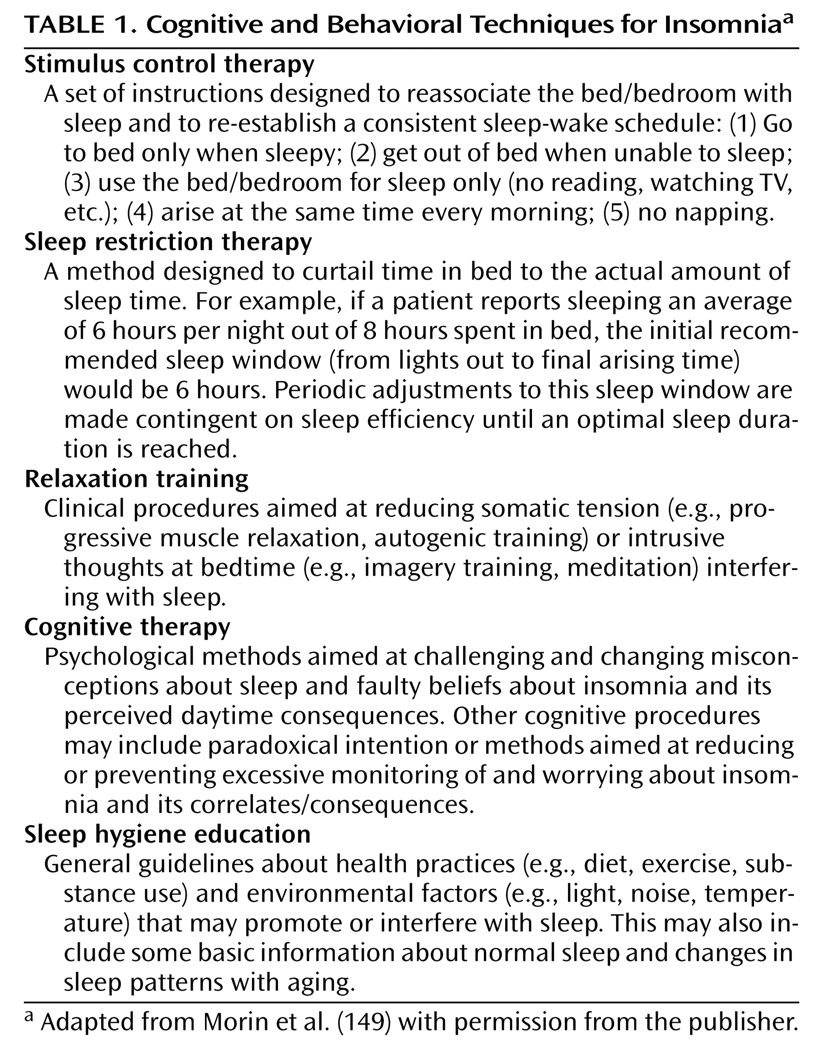

115) . Strategies of CBT-I can include sleep restriction therapy, sleep hygiene education, stimulus control therapy, and relaxation training (

Table 1 )

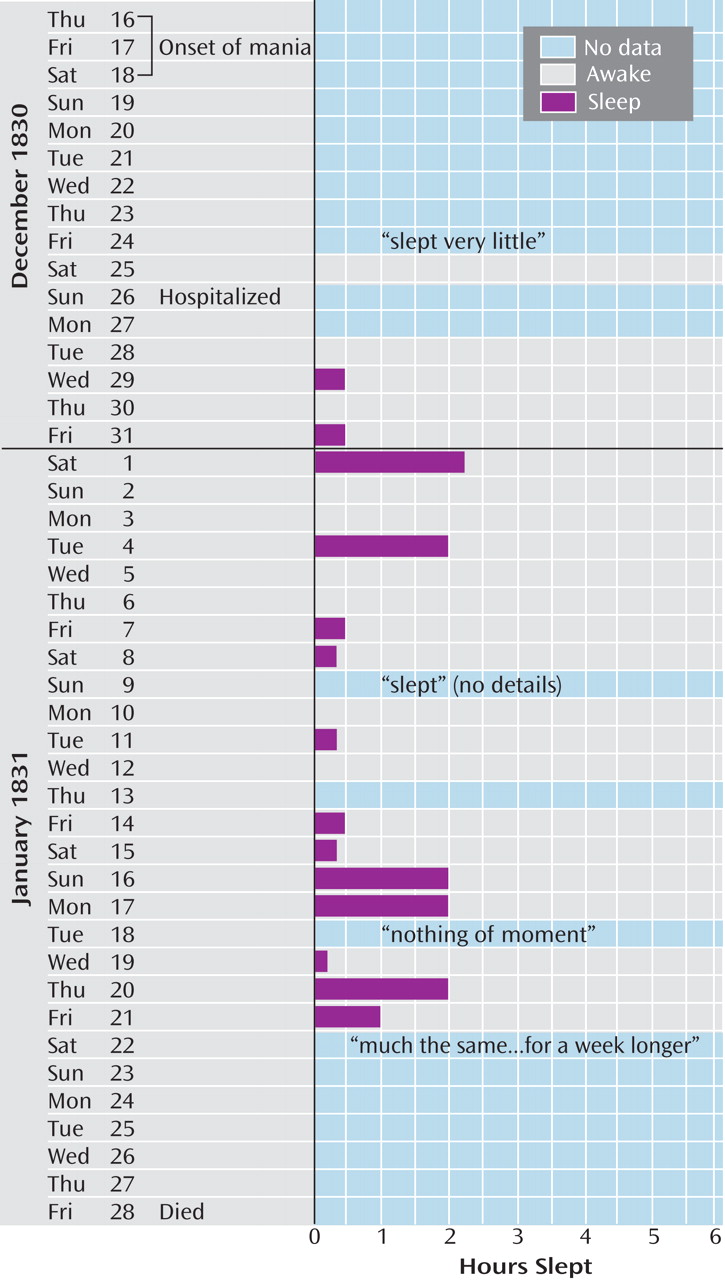

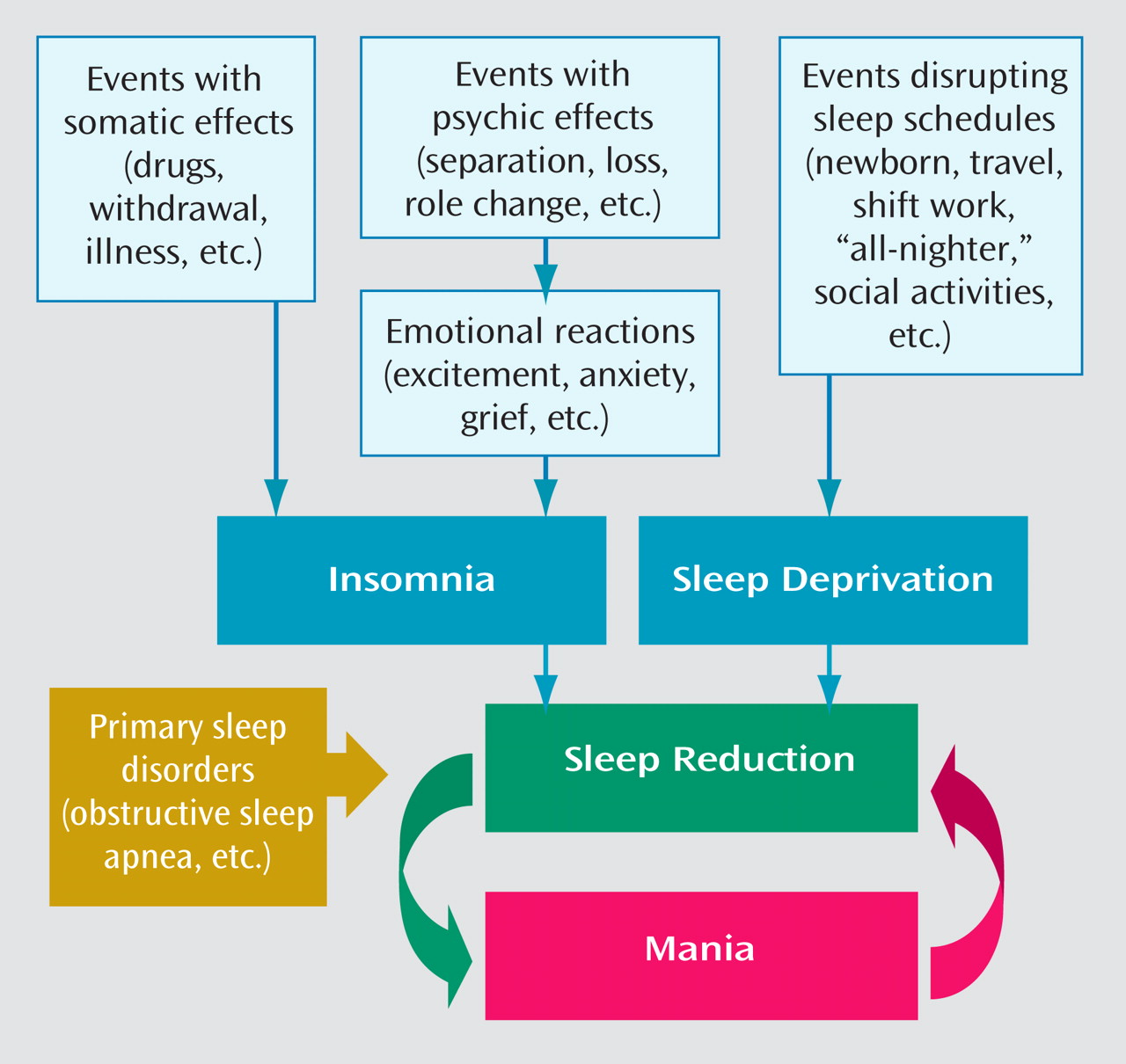

(116) . Unfortunately, there are no studies of CBT-I in bipolar insomnia, although most of these techniques could probably be applied without fear of negative outcome in bipolar patients. The exception is sleep restriction therapy, in which time in bed is limited to the number of hours the patient believes he or she is sleeping, which could increase the chances that a bipolar patient will switch to mania

(117) . Unfortunately, sleep restriction is considered one of the most efficacious CBT-I techniques, and hence the overall value of CBT-I may be limited in bipolar disorder

(118) . Management of insomnia in bipolar patients using CBT-I also may be complicated by the fact that bipolar patients (particularly those who are rapid cycling) often complain of difficulty arising in the morning and can have mild hypomanic symptoms that intensify over the course of the day, potentially disrupting their ability to sleep at night or adhere to prescribed CBT-I interventions

(119,

120) .

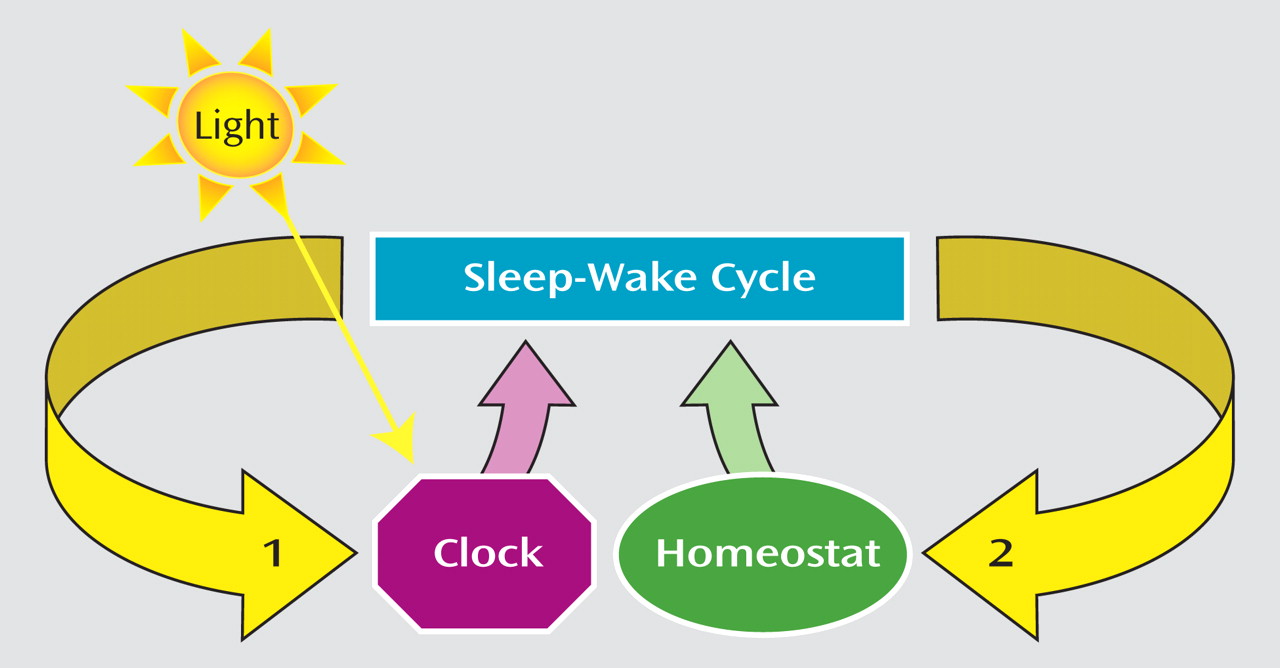

Psychotherapies used successfully in the treatment of bipolar disorder utilize psychoeducational components that emphasize identification of prodromal symptoms (e.g., sleep disturbance) and the importance of lifestyle regularity, including stabilization of sleep-wake rhythms

(121) . Colom et al.

(122) found that group psychoeducation significantly reduced the number of patients who relapsed and the number of recurrences per patient, as well as the time to recurrences (depressive, manic, hypomanic, and mixed). Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, which is based on the notion that management of life stressors that disrupt patterns (e.g., social patterns, sleep-wake patterns) may improve outcomes in bipolar disorder, has been shown to prolong maintenance and decrease affective relapse

(123,

124) . Similarly, cognitive-behavioral treatments for bipolar disorder often stress maintenance of sleep-wake patterns through psychoeducational and/or cognitive-behavioral approaches and have been shown to be an efficacious modality in bipolar disorder

(125,

126) .

Pharmacotherapy for Bipolar Insomnia

The empiric pharmacological treatment of insomnia in bipolar disorder includes benzodiazepines, benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BzRAs), sedating antidepressants, anticonvulsants, sedating antipsychotics, and melatonin receptor agonists. Here we briefly discuss the pros and cons of these medications in the context of bipolar disorder, with the caveat that no medication has been specifically approved for management of insomnia in bipolar disorder.

Benzodiazepines, long considered first-line therapy for insomnia, offer several benefits in the treatment of insomnia, including known efficacy and a wide range of half-lives. No studies have directly demonstrated that using benzodiazepines to improve sleep also improves mood stability in bipolar patients, nor have any controlled trials examined the use of benzodiazepines in prodromal phases of mania. However, in both an uncontrolled retrospective chart review and a prospective open trial at the same institution, clonazepam was found to be effective as a replacement for neuroleptics used adjunctively with lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder, although two other trials did not have success with this approach

(127 –

130) .

The potential for abuse, tolerance, withdrawal, daytime sedation, and motor/cognitive impairment is often a limiting factor in the use of benzodiazepines for the treatment of insomnia. BzRAs (e.g., zolpidem, zaleplon, and eszopiclone) are similar to traditional benzodiazepines in that they work at the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor, but they are more specific to GABA

A receptors containing α-1 subunits. All have short to intermediate half-lives, which reduces the likelihood of daytime carryover and the resultant side effects. Although BzRAs also have potential for tolerance and withdrawal, there is evidence that non-nightly use of BzRAs over 8–12 weeks is not associated with such sequelae

(131,

132) . Furthermore, newer agents have been studied for extended durations (up to 6 months) without evidence of tolerance or rebound insomnia on discontinuation

(133,

134) . Although BzRAs are clinically used as hypnotics in bipolar insomnia, we know of no studies to date examining their use as adjunctive medications in the management of bipolar disorder.

Despite evidence that benzodiazepines and BzRAs are effective for insomnia, the agents most commonly prescribed to treat chronic insomnia are sedating antidepressants at low dosages

(135) . Their use in insomnia has increased dramatically since the early 1990s, probably as a result of concerns about long-term use of BzRAs (including label restrictions on duration of use), widespread use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in treating depression (which, in contrast to the older antidepressants, are not sedating and may in fact be alerting), and restrictions on access to branded BzRAs by health maintenance organizations. Trazodone and other antidepressants, particularly tricyclics, are known to have the capacity to induce mania in bipolar patients, and there is limited evidence that trazodone may somewhat paradoxically induce manic switching more rapidly than SSRIs

(136 –

138) . Thus, we recommend that sedating antidepressants, even at low dosages, be used with caution in patients with bipolar disorder.

Anticonvulsants that are not approved for the treatment of bipolar disorder (gabapentin, topiramate, and tiagabine) are also sometimes used off-label as hypnotics in bipolar patients. This is likely because they are sedating and are not associated with manic switching, and because some other anticonvulsants have demonstrated mood-stabilizing properties. Again, there is little direct evidence to support this strategy specifically in bipolar patients. However, there is some suggestion that gabapentin can improve subjective sleep quality, decrease light sleep, increase REM sleep, and possibly increase slow-wave sleep

(139) . Similarly, tiagabine may increase slow-wave sleep, although its usefulness as a hypnotic in primary insomnia is limited

(140) . These agents are probably less effective than benzodiazepines and BzRAs in the treatment of insomnia, and their side effects (cognitive impairment, daytime sedation, etc.) should be considered before prescribing them as hypnotics in bipolar disorder.

Antipsychotics, in particular atypical antipsychotics, are frequently used as adjunctive or primary agents in bipolar disorder, often with the intention of improving sleep, and these agents have gained popularity as off-label sedative-hypnotics in the general population. However, use of antipsychotics solely as hypnotics is controversial, especially given their propensity to cause metabolic abnormalities, daytime sedation, and weight gain and their risk of extrapyramidal symptoms

(141) . The antipsychotic most commonly used in clinical practice as a sedative-hypnotic is quetiapine, typically in low doses (25–100 mg), which has been shown to increase total sleep time and improve subjective sleep quality in healthy subjects

(62) . However, clinicians should be cautious in using antipsychotics in the management of bipolar insomnia because antipsychotics may induce or worsen sleep-related movement disorders, such as restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements of sleep, which may paradoxically diminish quality of sleep

(62,

142,

143) .

Drugs that act on the melatonin receptor, such as ramelteon and exogenous melatonin, may be useful in the management of bipolar insomnia, particularly in patients with comorbid substance use, as these agents are not associated with any risk of abuse

(144,

145) . Although melatonin has shown some promise in treatment-refractory mania in rapid-cycling patients, melatonin and melatonin receptor agonists have not been carefully studied in maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder

(64) . A case series of five euthymic rapid-cycling patients suggested that exogenous melatonin had little effect on mood or sleep, although melatonin withdrawal delayed sleep onset time and may have had mild mood-elevating effects

(146) . Thus, the use of agents that target the melatonin receptor in bipolar patients requires further investigation.