Establishing diagnostic criteria is an iterative process, beginning with a listing of clinical observations and revising these criteria as more empirical evidence is collected

(12,

13) . Traditional tests of the validity of these criteria entail demonstration of etiology, pathogenesis, illness course, including response to treatment, and familial patterns. Few diseases have one necessary and sufficient cause or pathognomonic indicators. Most, e.g., coronary artery disease, cancer, and Parkinson’s disease, result from a mixture of etiologies and complex pathogenesis

(12,

14) . Because the etiology and pathogenesis of most psychiatric disorders remain largely unknown, diagnostic validity in psychiatry is largely limited to follow-up studies of illness course, response to treatment, and family studies

(12) .

Robins and Guze proposed a procedure for validation of psychiatric diagnoses nearly 40 years ago

(15) . First adopted by DSM-III in 1980, this process revolutionized definitions of psychiatric disorders, most recently formalized in DSM-IV-TR. This validation procedure entails five investigative phases: 1) clinical description (including symptom profiles, demographic characteristics, and precipitating factors), 2) laboratory studies (including psychological tests and radiological, chemical, and postmortem findings), 3) separation from other disorders (through exclusion criteria), 4) follow-up studies (demonstrating diagnostic stability and treatment response), and 5) family studies

(15) . A major strength of this approach is that it is agnostic and atheoretical regarding disease etiology. It avoids premature constraint to assumed etiologies and facilitates research exploring potential causal pathways. Diagnostic criteria have been validated by these methods for more than a dozen psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, antisocial personality disorder, and alcohol use disorders). The remaining 200+ diagnoses in DSM-IV-TR, however, await completion of focused validation of their diagnostic criteria through these rigorous and systematic methods

(14,

16) .

PTSD is not among the diagnoses most completely validated by this process. This does not mean, however, that the diagnosis is necessarily invalid or that its criteria cannot be validated. To the contrary, we propose in this article that further validation research can suggest potential improvements based on empirical testing of proposed alternative diagnostic criteria yielding greater homogeneity in family patterns, longitudinal stability, biological indicators, and differentiation from other disorders.

Empirical Research on PTSD

In 1987, Breslau and Davis wrote, “There is as yet little empirical research on the validity of the diagnosis” of PTSD (p. 255)

(17) . In 1988, a workshop convened by the National Institute of Mental Health outlined research needed to validate the diagnosis of PTSD

(9) . It determined that existing criteria lacked validating evidence pertaining to characteristics of the traumatic stressor, coherence of the observed syndrome, and supporting evidence demonstrating a consistent longitudinal course, familial associations, and relationship to other syndromes.

Nearly two decades later, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academy of Sciences reviewed existing evidence supporting diagnostic validity of PTSD through application of the five historical validation phases

(18) . Although designed to be illustrative rather than comprehensive, the IOM report found considerable evidence supporting the first phase of clinical description. What was disappointing in our view was the limited research supporting the remaining four phases (biological markers, separation from other disorders, and follow-up and family studies).

The IOM report described inconsistent findings from major lines of investigation into PTSD. Hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis and brain imaging abnormalities appear contradictory and not necessarily specific to PTSD. Several studies indicate genetic predispositions, with PTSD heritability estimates ranging around 30% to 40%, but investigations of candidate genes, e.g., serotonin (5-HTT) and dopamine (DRD2, DAT), have yielded variable results. PTSD has been differentiated from other disorders only by expert conceptualization

(19) but not in actual patients. Although apparent symptom overlap with other disorders may represent a potential threat to differentiation from other disorders required for diagnostic validation

(3,

4,

7,

20 –

23), methodological problems, especially nonadherence to established criteria, have limited this line of research. Comorbidity is typical for PTSD but also occurs with other valid diagnoses and does not automatically disqualify the diagnosis from validation

(18) . Follow-up studies have examined the serial prevalence of PTSD over time, but few have presented findings on the longitudinal course of individual cases needed to determine diagnostic stability. Studies of familial associations in PTSD have been largely limited to family history obtained from probands rather than examining family members. PTSD research has demonstrated familial associations with other psychopathology but not PTSD.

The evidence for the other four diagnostic validation phases for PTSD is destined to remain limited until the evidence for the first phase—description of clinical characteristics—is more fully established. This first validation phase is, in our view, particularly important because it provides a specific set of defining clinical attributes as a foundation on which other phases (follow-up, family, exclusion, and biological studies) are based. Robins and Guze’s determination of valid diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia made possible a generation of research into its genetics and neurobiology. A similar solidification of the diagnosis of PTSD is needed to permit meaningful research into its causes and treatment.

The Trauma Criterion

The most controversial aspect of PTSD validity is paradoxically the organization of PTSD’s definition around a potentially causal event (the traumatic “stressor criterion”). Fundamental to PTSD conceptualization, this criterion creates formidable difficulties for clinicians and researchers alike

(2,

3,

6,

22,

24,

25) . PTSD differs from other psychiatric diagnoses by its inherent dependence on two distinct processes: first, exposure to trauma, and second, development of a specific pattern of symptoms in temporal and/or contextual relation to the traumatic event.

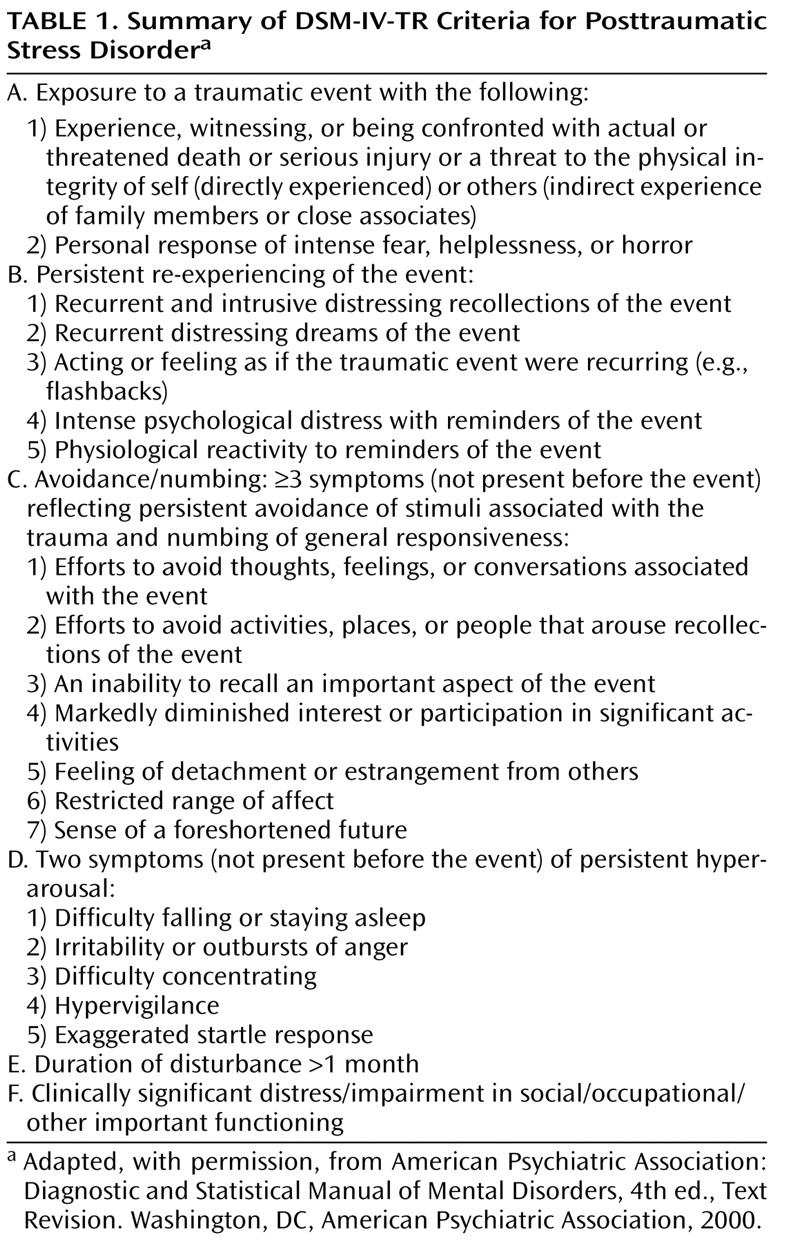

PTSD, as originally conceptualized and currently defined in DSM-IV-TR, occurs only in conjunction with trauma exposure (see summary of diagnostic criteria in

Table 1 ). Criterion A specifies that the individual must have been sufficiently exposed to a stressor qualifying as traumatic to be a candidate for a PTSD diagnosis. Without sufficient exposure to a qualifying traumatic event, symptoms cannot be considered contributory to the diagnosis. Symptoms occurring in association with nonqualifying (possibly stressful but not classifiably traumatic) events (e.g., being fired, being sued) might alternatively be subsumed under the diagnosis of adjustment disorder

(6) or could be part of depressive or anxiety disorders—or even simply distress that is not part of a recognizable psychiatric disorder.

By definition, PTSD may occur in association with a range of trauma types, e.g., natural disasters and terrorism, rape and other assaultive violence, military combat, and accidental injuries. Trauma types demonstrated most commonly associated with PTSD are rape, kidnapping, and torture

(26) . The qualification of such extreme trauma is generally undisputed, but questions have arisen about whether other stressors should qualify, such as purely psychosocial events without immediate physical injury or threat (e.g., divorce, failing an important examination). Mounting pressure to broaden the definition of qualifying events has been countered by protestations over “bracket creep”

(2,

27) . Criteria have accordingly been altered in successive DSM editions. Previously defined as “markedly distressing to almost anyone,” a qualifying stressor now requires threat to “physical integrity”—i.e., to life or limb. Such trauma, however, does not have to be directly experienced; witnessing or “being confronted with” (hearing about a traumatic experience of a family member or other “close associate”) also qualifies. In addition, DSM-IV added a subjective component (response of intense fear, helplessness, or horror—criterion A2).

Leading trauma researchers have long recognized problems of confounding of descriptive characteristics (symptoms and other characteristics) with purported etiology (a traumatic stressor)

(17,

28,

29) . Continuing debates over the trauma criterion have revolved around the type of qualifying traumatic event (and the requisite degree of exposure to it) and whether or not the definition should even require such an event, or even any stressor. One suggested solution is to simply remove the requirement of a stressful event from the definition. Two decades ago, researchers

(17,

28,

29) recommended assessment of etiological agents and their effects independently to unconfound them operationally, allowing observable symptom patterns to clarify the types of events that are associated with PTSD. In this seemingly backward approach, the type of event would function as a dependent variable predicted from the associated symptoms.

Others, however, remain adamant that PTSD be defined around a traumatic event—the essence of what makes it distinctly PTSD

(5,

21,

28,

30) . Breslau and colleagues

(21) noted that the link of symptoms to a specific traumatic event “transforms the list of PTSD symptoms into a distinct DSM disorder” (p. 574). They cautioned that severing the definitional link between the symptoms and a traumatic event distorts the integrity of the diagnosis. Breslau mused

(30), “Without exposure to trauma, what is posttraumatic about the ensuing syndrome?” (p. 927). We agree and whimsically propose that a syndrome following a nontraumatic stressor might more appropriately be named “poststressor stress disorder” and one associated with no identified stressor called “nonstressor stress disorder.”

Basing the definition of PTSD on a required traumatic event and an associated set of symptoms introduces causal complexities. The risk factors for exposure to a traumatic event may differ from those conferring the likelihood of psychiatric illness afterward. Attempts to assign causality to a syndrome defined in relation to two processes with different sets of risk factors are thus confounded. Breslau

(30) noted, “Personality traits of neuroticism and extroversion, early conduct problems, a family history of psychiatric disorders, and preexisting psychiatric disorders are associated with increased risk for exposure to traumatic events” (p. 926). Thus, a portion of the psychopathology observed after trauma may simply represent an extension of the preexisting risk factors for exposure. We caution that a definition automatically assigning causality of the ensuing syndrome to the preceding traumatic event fails to allow alternate causal possibilities, oversimplifies relationships, and obscures the importance of scientific inquiry into causality.

Recently, Maier

(31) concluded that current conceptualizations of PTSD widely embraced by professionals and the public alike promote inappropriate monocausal assumptions regarding traumatic events and associated mental health difficulties. Basing diagnostic definition on etiology, in his estimation, creates a tautology blurring pre-event, peri-event, and postevent factors. He stressed that defining PTSD etiologically deviates from the explicitly stated goals of diagnostic manuals to define diagnoses phenomenologically, avoiding etiological assumptions. Maier urged the field to shun simple causal models, instead promoting an understanding of PTSD as “a multifactorial disorder just like any other mental disorder, even when a single external factor still may be identified as particularly important and indispensable for the emergence of the disorder” (p. 105). We find these concerns vital to furthering PTSD research and establishing diagnostic validity.

Because causality is problematic to the definition of PTSD, yet the inclusion of a traumatic event is considered essential to PTSD, we propose an achievable solution through adoption of a descriptive approach to its definition that requires a traumatic event without invoking causal assumptions. DSM-IV-TR already does this, merely stating that the associated symptoms follow the event and refraining from assigning causality to the traumatic event: “The essential feature of posttraumatic stress disorder is the development of characteristic symptoms following exposure to an extreme traumatic stressor” (emphasis added) (p. 463). This definition allows research to proceed unimpeded to test etiological hypotheses from monocausal to complex causal models, ultimately enabling empirical findings rather than opinions to settle disputes. This subtle but important attention to wording of the relationship encourages research to examine untested causal assumptions. However, an inconsistency occurs two sentences later, with causality inadvertently ascribed: “The characteristic symptoms resulting from the exposure to the extreme trauma include…” (emphasis added). Although Maier considers the “A criterion” to be invalid and noncontributory to the diagnosis, for sociopolitical reasons, he ultimately recommended retaining the traumatic event within the definition of PTSD to preserve the obvious association of trauma with the symptoms. Thus, even in the minds of those who advocate definitional separation of stressor and symptom, the tie remains.

The Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks introduced further complexities for interpretation of criterion A1

(32) . The burning Twin Towers could be viewed from a distance of miles; and both live and replayed television coverage brought graphic images into every home in real time and for days and weeks afterward. All of these September 11th experiences might conceivably be considered a form of witnessing. As written in DSM-IV-TR, the “witnessing” specification does not require one to be an

eyewitness or even observe the scene from a circumscribed proximity. Numerous studies related to September 11th reported on the prevalence of PTSD among populations of Manhattan and Washington, DC, and surrounding areas, and in national samples as far away as Houston, Tex., and Los Angeles

(33 –

36) . Presumably, most of the people in these locations had not been personally present at the site and did not have a close friend or family member who was injured or killed or directly endangered by the attacks. Thus, they must have been considered PTSD candidates (and many were identified as having PTSD) through viewing television coverage of the attacks, hearing about it, or somehow perceiving that they too were endangered. The above studies carefully represented the findings not as PTSD but as “stress symptoms,” “symptoms of PTSD,” and “probable PTSD.” We agree with Silver and colleagues

(36), who cautioned that such symptoms do not necessarily imply psychopathology but may represent normal responses to an event of extreme proportions. The significance of PTSD “symptoms” outside the context of diagnosis is unclear.

Only 5% of a post-September 11th Manhattan sample assessed for PTSD resided south of Canal Street (within ∼1.5 miles of the World Trade Center); 37% “directly” witnessed the attacks, 11% said a family member or friend was killed in the attacks, and 11% reported involvement in rescue efforts

(33) . These vague exposure categories did not differentiate, for example, between observing the attacks from the base of the towers and seeing them from several miles away or between losing a spouse and hearing that a distant friend or acquaintance had been killed in the attacks. Some 6% of people

without direct exposures had “symptoms consistent with PTSD,” and those

with exposures were about two or three times more likely to report such symptoms.

Empirical study is needed to test the associations between stressor types and related symptom patterns. Precise definitions for provisional categories of types of traumatic events and levels of exposure to them (e.g., direct threat to life or limb, eyewitness to an event, and indirect exposure through a loved one exposed to an event) must be adopted and operationalized to compare associated syndromes by exposure type, confirming and/or further refining the diagnostic criteria. Once this is accomplished, research can assess whether psychopathology following exposure to events qualifying as traumatic under DSM-IV-TR criteria can be differentiated from psychopathology in people without sufficient exposure or with exposure to a nontraumatic event they perceive as stressful. We agree with the admonishment by Weathers and Keane

(5) that an excessively broad definition could “hinder research by increasing heterogeneity of participants” (p. 112). Although it remains to be tested, we suspect that nontraumatic stressors (e.g., being fired, being divorced, suffering a large financial loss) and distant exposures to traumatic events, such as hearing of injuries and deaths of far-away strangers, will not be found to yield an identical syndrome with similar prevalence to that following direct exposure to traumatic stressors such as surviving a plane crash.

Progress has been made toward investigating the effects of applying different criteria for traumatic events. Breslau and Kessler

(24) empirically demonstrated an altered prevalence of traumatic events and PTSD resulting from DSM definition evolution. Changes between DSM-III-R and DSM-IV increased criterion A1-qualifying traumatic events by 59%, mostly related to hearing of the sudden unexpected death of a loved one. New application of the A2 criterion, however, limited the increase of criterion A (A1 and A2)-qualifying events to 22%. The A2 criterion added little to ultimate diagnosis, as very few people not endorsing intense fear, helplessness, or horror met the symptom threshold. Thus, it was suggested that the A2 criterion might be most useful as a screener to rule out cases unlikely to meet full criteria. Overall, 38% of DSM-IV-determined PTSD cases were attributable to definitional expansion by inclusion of new event types.

PTSD Symptoms

Although the trauma criterion has been controversial, research on the symptom criteria has made substantial progress. The diagnosis of PTSD requires assessment of 17 trauma-associated symptoms divided into three groups: B (requiring ≥ 1 intrusive memories of the event), C (requiring ≥ 3 avoidance and numbing responses), and D (requiring ≥ 2 hyperarousal symptoms). In DSM-III, PTSD included only the intrusion and avoidance/numbing symptom groups; the hyperarousal symptom group was not added until DSM-III-R in 1987. The group C criteria have been criticized as being relatively too stringent and restrictive for optimal definition of PTSD

(37,

38) . It has alternatively been argued that the group B and D criteria are relatively too sensitive to be of use in the differentiation of psychopathology from distress

(38) .

Several research groups examined the relative contribution of symptom group criteria to the full diagnostic criteria for PTSD and concluded that the avoidance/numbing cluster (group C) is a strong determinant of PTSD

(32,

37 –

42) . Traumatized individuals are usually two or more times as likely to meet groups B and D criteria than C criteria

(37,

38,

40,

41) . Breslau et al.

(42) pointed out that relative to group B and D criteria, group C criteria present a higher threshold, effectively making group C a rate-limiting factor for the diagnosis. In part, this may be because the group C criteria require three-sevenths (43%) of avoidance/numbing symptoms, compared to group B, requiring one-fifth (20%) of intrusive reexperience symptoms, and group D, requiring two-fifths (40%) of hyperarousal symptoms. Based on the relative number of symptoms in each group, group B has a proportional advantage over groups C and D for fulfilling symptom group criteria. The relatively infrequent fulfillment of group C criteria, however, ultimately relates to individual symptom frequency. In traumatized populations, group C symptoms present less frequently than group B and D symptoms

(28,

37,

40,

41,

43) .

Group C criteria may be more than just contributory to the diagnosis of PTSD as currently defined. Experts have observed that the C symptom group is “largely responsible” for the diagnosis (p. 516)

(37), “the critical one for a diagnosis of PTSD” (p. 16)

(44), and “central to the diagnosis of PTSD” (p. 59)

(39) . Maes and colleagues

(38) wrote that the diagnosis “relies only on the criterion C symptoms [and] symptoms belonging to criteria B and D are not needed” (p. 189). Previously, we observed that 94% of directly exposed Oklahoma City bombing survivors who met group C criteria (i.e., meeting ≥ 3 avoidance/numbing symptoms) met full DSM-III-R criteria, compared to (by definition) none of those not fulfilling group C criteria

(40) . Further, symptom groups B and D by themselves, in the absence of fulfillment of group C criteria, did not predict PTSD. These and similar findings from bombing survivors in Nairobi, Kenya

(45), and studies of other researchers as noted above led us to conclude that, based on the organization of current diagnostic criteria and the manner of presentation of the symptoms in their trauma survivors, group C is a marker for PTSD.

Among Oklahoma City bombing survivors, we found that meeting group C criteria was also significantly associated with self-reports of preexisting psychopathology, postdisaster comorbidity, seeking mental health treatment, taking psychotropic medication, drinking alcohol to cope, and difficulties in functioning

(40) . In the absence of group C, however, groups B and D did not predict these associated indicators of psychopathology. Group B and D symptoms were quite common, with about 80% of the sample meeting these symptom group criteria, compared to only 36% meeting C criteria and 34% meeting full PTSD criteria.

These findings have been confirmed by others. Breslau’s group

(42) also found in community samples that meeting group C criteria after a traumatic event was associated with seeing a physician, taking medication for the disturbance, and functional impairment from posttraumatic symptoms. In a study of emergency room trauma survivors, Shalev’s group

(46) also observed that group C symptoms predict psychiatric illness and comorbidity. In a study of injured survivors of a terrorist attack on a civilian bus, Shalev

(47) further noted that the pervasiveness of B and D symptoms limited their specificity for PTSD. Given the saturation of B and D symptoms in traumatized populations and their lack of association with other indicators of psychopathology in the absence of group C among Oklahoma City bombing survivors, we concluded that the group B and D symptoms in general appear to represent normative responses which, by themselves, do not necessarily indicate psychopathology

(40) . Thus, while the relatively common group B and D symptoms signify distress, the less prevalent group C cluster serves as a marker of psychopathology.

Relationships Between Traumatic Events and Symptoms

The relationship of symptoms to traumatic events, which persists in the thinking of most scholars of PTSD despite attempts to separate them, is useful for efforts to refine the specificity of the symptoms of PTSD. Symptoms not defined by their association with an event are destined to be nonspecific to an event of interest and to suffer inadvertent contamination from individuals who habitually endorse high levels of distress. Studies of symptoms without association with a specific event have been overwhelmingly unsuccessful in identifying a characteristic set of symptoms

(4,

7,

20 –

23), demonstrating the essential nature of connecting symptoms to a traumatic event to define a coherent posttraumatic syndrome. Even the strongest association with an event, however, does not necessarily imply specific causality.

Taking care to evaluate posttraumatic symptoms according to criteria as currently specified by DSM-IV-TR may, on the surface, seem a subtle issue, but this distinction is critical to diagnostic validation and selection of the most homogeneous samples. Careful adherence to DSM-IV-TR will exclude unrelated symptoms not contextually tied to the event (e.g., requiring nightmares of the event rather than just any nightmares) or temporally tied to it (e.g., requiring new onset of insomnia, problems concentrating, or loss of interest after the event, rather than just the presence of these symptoms after the event).

Biological Observations

Confirming our own observations of the importance of relating traumatic events and subsequent symptoms

(40), Yehuda and McFarlane

(23) clarified distinctions between psychopathology and normative distress following trauma and emphasized that most trauma survivors do not develop psychopathology. They concluded that demonstrated differences between the biology of PTSD and the biology of normative distress response support the concept of PTSD as a disorder distinct from distress. Biological findings they identified as distinguishing PTSD from normative distress are HPA axis abnormalities (decreased baseline cortisol and increased negative feedback regulation, suggesting HPA axis oversensitivity) and physiological, electrophysiological, and neurochemical aberrations in the regulation of sympathetic nervous system and other neuromodulatory systems.

These findings suggest that a vital step in advancing PTSD research is the convergence of nosological, epidemiological, and biological lines of investigation. Strong collaborations among traumatology biologists, epidemiologists, and nosologists will be needed to map the correspondence between the clinical and biological indicators of psychopathology and further differentiate them from normative responses to trauma. For example, epidemiologic evidence that avoidance and numbing represent a core aspect of psychopathology in PTSD suggests an approach to mapping biological findings, such as HPA axis and imaging abnormalities, to these clinical findings. In contrast, physiological correlates of ordinary stress response may be demonstrated in relation to intrusion and arousal alone. Differentiating the biology of normative trauma response and psychopathology following traumatic exposure through combined epidemiological and biological streams of investigation will be critical to the future understanding of PTSD.

The Demographics of PTSD

Just as biological studies form one test of the validity of PTSD, coherence across different demographics constitutes another potentially validating element. Population studies and disaster research have consistently shown that women have approximately twice the rates of PTSD of men

(48 –

50) .

PTSD has been documented in developed and undeveloped countries alike, in settings of war and mass violence and with endemic accidental trauma during peacetime. Attempts to compare PTSD in trauma survivors of different countries and continents have historically been limited by noncomparable research methods. Using structured diagnostic interviews, our team has documented remarkable cross-national similarities in PTSD between civilian groups in the United States (Oklahoma City) and Kenya (Nairobi) directly exposed to terrorist bombings

(45) . The incidence of PTSD by gender was similar among survivors in the two countries (20%–30% in men and 40%–50% in women). In both sites, group C was strongly predictive of a diagnosis of PTSD. Both groups overwhelmingly depended on support from loved ones to help them cope. Secondarily, Nairobi, Kenya, survivors were inclined to seek comfort from their religious community, whereas Oklahoma City survivors favored medical treatment, medications, and alcohol for coping. Thus, the expression of PTSD itself was more similar than different in the two sites, but coping responses differed.