In their functional magnetic imaging (fMRI) study of unmedicated patients with generalized anxiety disorder, Nitschke and colleagues

(1) show us how the fMRI method can provide us with new insights into the cognitive and neural mechanisms of a common anxiety disorder. The study generalized anxiety disorderalso provides us with an additional clue as to the neurobiological basis of resiliency and treatment responsiveness in this condition. Informed by previous literature implicating-overhyperactivation in the amygdala in the anterior medial temporal lobes, in both anxiety and depression, the authors presented cues to subjects in the scanner that indicated that subjects were about to view either a negative picture or a neutral one. Subjects were scanned for a period of 2.5 to 4.5 seconds after they viewed the cue as well as during the picture. Compared to the healthy group, patients with generalized anxiety disorder showed increased post cue (pre-picture) anticipatory activity bilaterally in the dorsal amygdala. Of interest, this increased activity was seen after cues indicating a forthcoming neutral picture as well as those indicating a negative picture.

The link between activity in the amygdala, with its strong role in the neurobiology of fear and other aspects of emotional responsiveness, including stress and arousal, suggests a neurobiological mechanism underlying the anticipatory worry and associated physiological arousal that characterizes the generalized anxiety disorder syndrome. The fact that this enhanced anticipatory response is also seen when generalized anxiety disorder patients are cued that they will see a nonaversive picture is also very interesting and may shed some light on the abnormal cognitive and emotional processing that characterizes generalized anxiety disorder. This somewhat unexpected finding might reflect an overall enhanced anticipatory emotional responsiveness in generalized anxiety disorder. Other studies have reported that the amygdala responds to positive as well as negative stimuli

(2), and it is possible that the neutral cues are emotionally salient for the generalized anxiety disorder group, experienced as positive perhaps in the context of the negative cues. This would indicate that generalized anxiety disorder is associated with a general overresponsiveness in an amygdala-based anticipatory arousal system. These possibilities could be tested by presenting each cue type in a blocked manner or including positive stimuli, perhaps mixed with neutral ones. An alternative interpretation of the results would reflect the requirement that in order to ensure subjects were on task they were required to press a button indicating whether the cue and the picture matched (on a small proportion of trials they did not) so that neutral cues were rarely followed by negative pictures. It is possible that generalized anxiety disorder patients overestimate the probability that a negative picture will follow a neutral cue (though this happens only once in 25 trials) and anticipate a negative picture even after a neutral cue. This would indicate a cognitive bias rather than a general, amygdala-based, anticipatory overactivity. Additional studies that vary the likelihood of negative pictures following neutral or positive cues could address this concern and clarify whether the excessive amygdala activity seen in the generalized anxiety disorder group is driven by anticipation of negative outcomes or by enhanced anticipatory activity to a range of emotionally salient outcomes.

Amygdala overhyperactivity is seen in depression as well as in anxiety disorders such as generalized anxiety disorder

(3,

4) . In the present study, individuals with prominent depressive symptoms or a recent depressive disorder were excluded and the Hamilton Depression Scale score for each patient was included as a covariate in the analysis in order to enhance the researchers’ ability to link their findings specifically to generalized anxiety disorder. On the other hand, generalized anxiety disorder, dysthymia, and major depression are frequently comorbid and may be expressions of a common underlying anxiety-depression diathesis. Whether or not the present findings of increased anticipatory activity to both negative and neutral cues are specific to generalized anxiety disorder could be very informative in this regard. It would be valuable to complete a comparable study in which patients with generalized anxiety disorder, other anxiety disorders (such as social phobia or panic disorder), and major depression were compared directly.

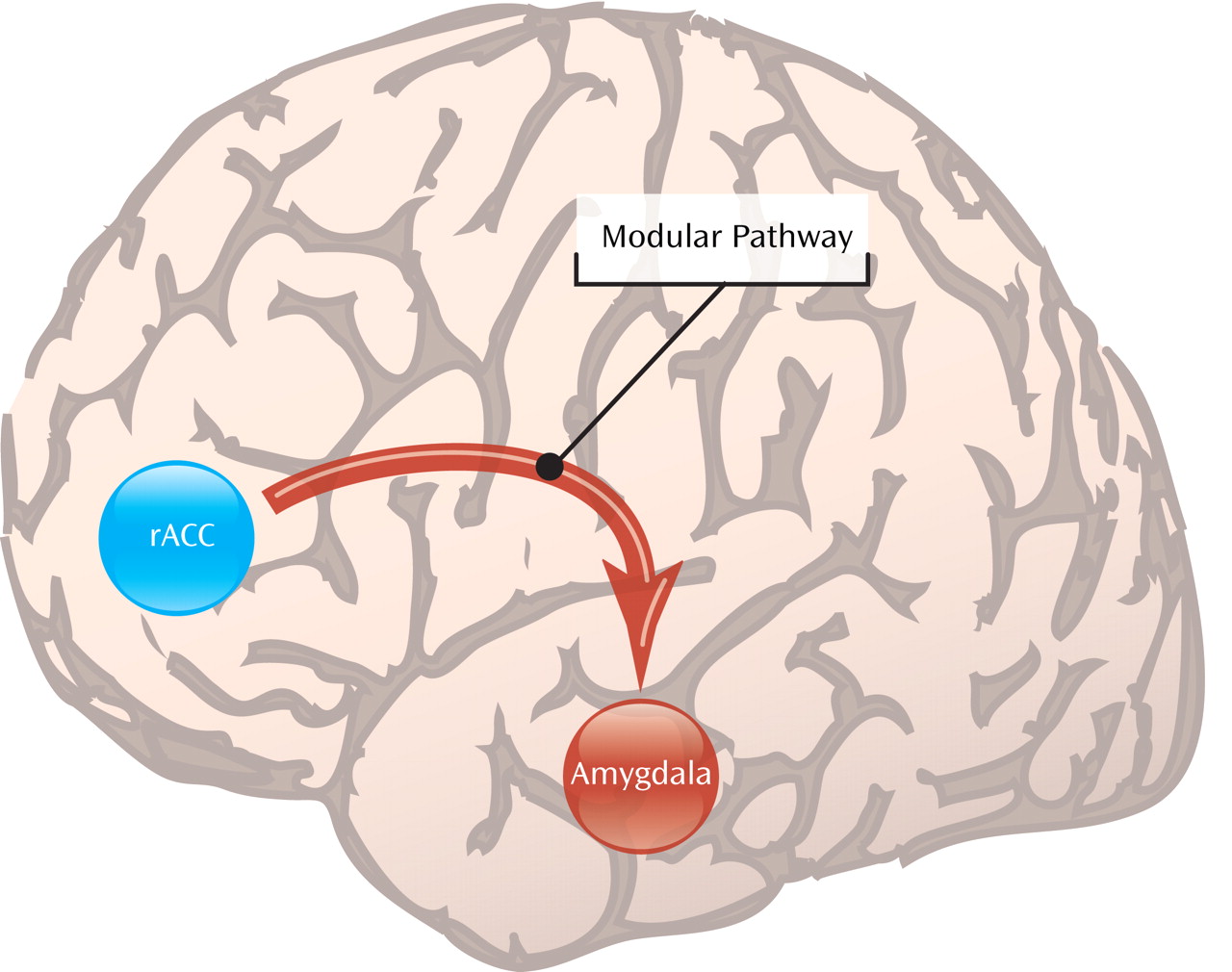

The second striking finding in the study by Nitschke et al. is that greater activation during picture anticipation of a region of the anterior cingulate cortex just in front or rostral to the genu of the corpus callosum predicted individual responses to a subsequent course of venlafaxine therapy. This is remarkable since previous studies

(5,

6) have shown a similar relationship between rostral anterior cingulate cortex activity and response to a variety of psychological and pharmacological treatments in depression. This suggests that higher levels of rostral anterior cingulate cortex activity are associated with resiliency and treatment responsiveness across depression and anxiety. The neurobiological mechanism underlying this relationship between activity and treatment response is likely due to the role of the rostral anterior cingulate cortex in modulating or suppressing the amygdala, with which it has rich reciprocal connections. A potential direct suppressive effect has been shown using fMRI in healthy subjects performing a task in which emotional distracters disrupted performance on a selective attention task

(7) . The rostral anterior cingulate cortex may also indirectly modulate the amygdala through its connections with the contiguous subgenual anterior cingulate cortex, which plays a key role in modulating fear extinction in the amygdala in both nonhuman animals and humans

(8) . In the present study, the relationship with positive treatment outcome is associated with cue-related activation, in some other studies in depression, it was with resting activity. Since amygdala hyperactivity seems to be a common feature across anxiety and depression, it follows that the integrity of a region whose function involves modulating the amygdala may be an important resiliency factor. Although this study clearly establishes cingulate cortex activity as a predictor of treatment response in generalized anxiety disorder, future studies could use fMRI to look at brain activity during and following treatment to better characterize the neural mechanisms that coincide with treatment success. It will be interesting to see if treatment success correlates with decreased amygdala response to cues and/or increased functional connectivity between the amygdala and the anterior cingulate cortex.

More work is needed to establish under which circumstances measurements of anterior cingulate cortex functional activity can be used in such a manner and in what diagnoses. However the clinical value of being able to identify those individuals who are most likely to be treatment responsive raises the possibility that fMRI, which has become widely available in the research setting in recent years, may become a useful clinical tool in the future. Further investigation of the mechanisms though which rostral anterior cingulate cortex functioning is associated with treatment responsiveness is also likely to yield new understanding of the neurobiology of depression and anxiety as well of resilience and treatment responsiveness in these disorders.