Reports of psychiatric symptoms form the basis of diagnostic protocols and serve as the primary source of information for evaluating patient functioning and prognosis. At present, research and clinical models are built on the assumption that an individual’s level of symptoms is the key predictor of impairment. Although there is good reason to believe that increased symptoms are associated with impairment, we know very little about how other dimensions of symptoms may affect behavior or relate to patient outcomes. Although symptoms for many common psychiatric disorders fluctuate significantly across time and context, this fluctuation receives little empirical attention

(1) . Indeed, symptom change and fluctuation are integral to conceptualizing the course of many common psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety, substance abuse). Yet, very little is known about how symptom variability is associated with patient functioning and long-term outcomes. For example, are troubled interpersonal relationships best predicted by static or dynamic measures of depressive symptoms? Is an individual’s poor job performance predictable from highly volatile patterns of anxiety symptoms? Do rapid changes in symptoms precede relapse during substance abuse treatment? Unfortunately, we have not been able to answer such questions because we lack methods for characterizing symptom dynamics. In this article, we use data from a unique sample of individuals followed intensively over 26 weeks and present a methodology for capturing symptom dynamics. We illustrate how systematic patterns of variability can be recovered from repeated symptom observations among high-risk individuals and then explore associations between symptom patterns and violence, a key indicator of psychological impairment. We focus on violence as a key marker of impaired functioning for three reasons. First, violence is commonly used by clinicians as a marker of individual impairment (e.g., as an item in the DSM-IV Global Assessment of Functioning Scale). Second, violence is a costly marker of impairment. Billions of dollars in health care-related expenses and productivity losses are estimated to be attributable to interpersonal and self-directed violence in the United States and elsewhere each year

(2,

3) . Third, the present sample was selected based on their high likelihood of recurrent violence. Therefore, it is of particular interest to test whether features of symptoms—other than symptom level—are associated with whether, and how often, violence occurs within this high-risk sample. Our prior work with this high-risk sample

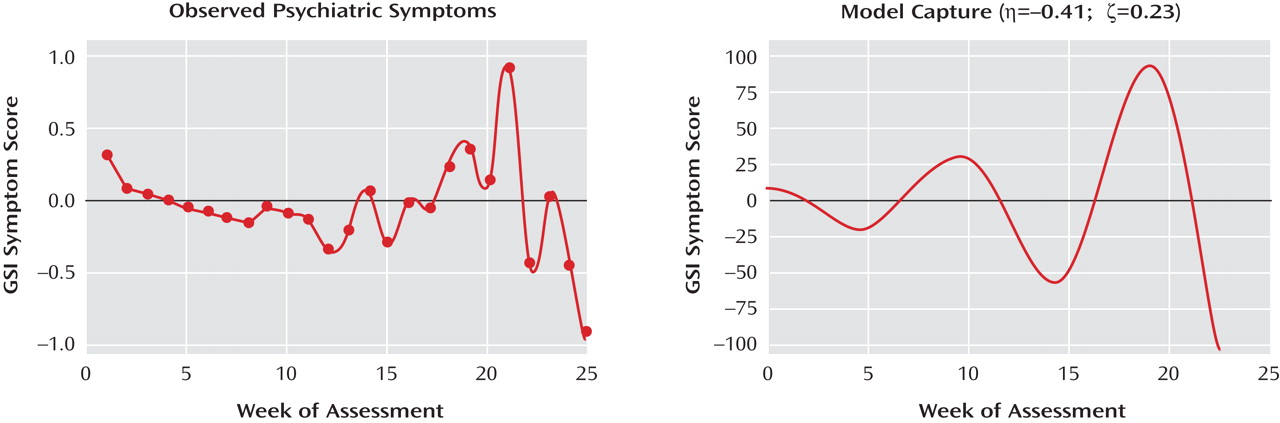

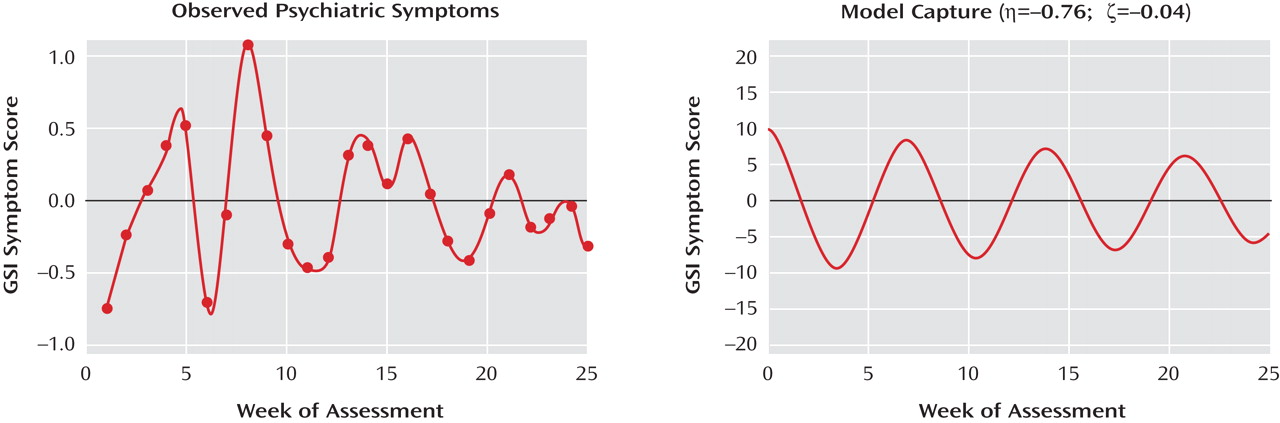

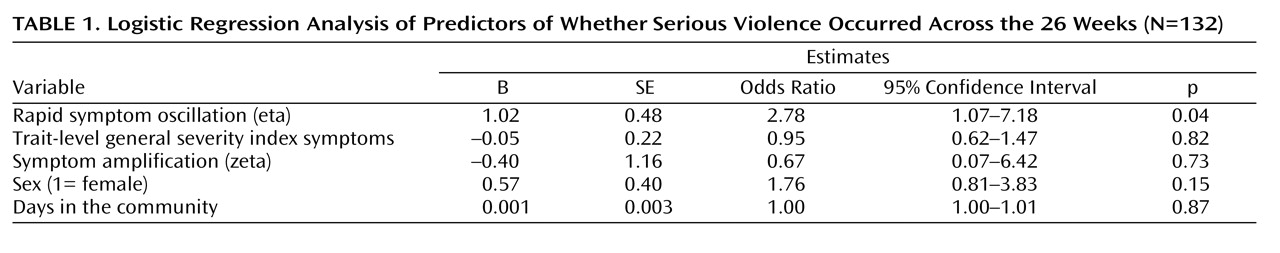

(4) demonstrated that elevated symptom levels (namely anger) increase the risk of violence the following week. However, our sole focus on symptom levels followed a long tradition of treating intraindividual fluctuations in psychiatric symptoms as noise, thereby ignoring potentially important and clinically useful information. The present analysis is innovative in that it applies a dynamic approach to test whether changes in symptoms from week to week within each individual demonstrate a systematic pattern or structure. The chief goal is to determine whether patterns of symptom (dys)regulation and oscillation can be reliably captured. We then explore whether parameters that summarize symptom fluctuation patterns over a 26-week period are associated with the occurrence of violence during that same period. A major reason to pursue this novel approach is that dynamical systems models align closely with how we conceptualize the course of many common psychiatric disorders. For example, depression has been characterized as a “dynamical disease”

(5) in which symptoms wax and wane over time and, in more extreme cases of bipolar disorder, diagnosis is based on the presence of rapidly cycling symptom patterns

(6,

7) . More generally, emotion regulation and related conditions have been described as oscillating systems

(8), whereby individuals fluctuate around a hypothesized equilibrium. Therefore, characterizing patterns of symptom fluctuation over time begins to bridge the chasm between theoretical conceptualizations of what psychiatric symptoms look like over time in an individual and the statistical models used to characterize them. The most common practices when assessing psychiatric symptoms are to rely only on a single snapshot (i.e., cross-sectional assessments) or to calculate a difference score between two or more assessment points (i.e., comparing pre- versus posttreatment symptoms levels)

(1) . The pervasiveness of static symptom assessments is unfortunate because there is a long history of interest in moving toward dynamic approaches for assessing symptom change in psychiatry

(9,

10) . Yet, with a few notable exceptions,

(11) symptoms continue to be conceptualized as dynamic entities but analyzed and measured as static indicators. In short, the time is now ripe for importing a new generation of models to capture complex symptom patterns, which are likely to be the rule rather than the exception for most psychiatric disorders

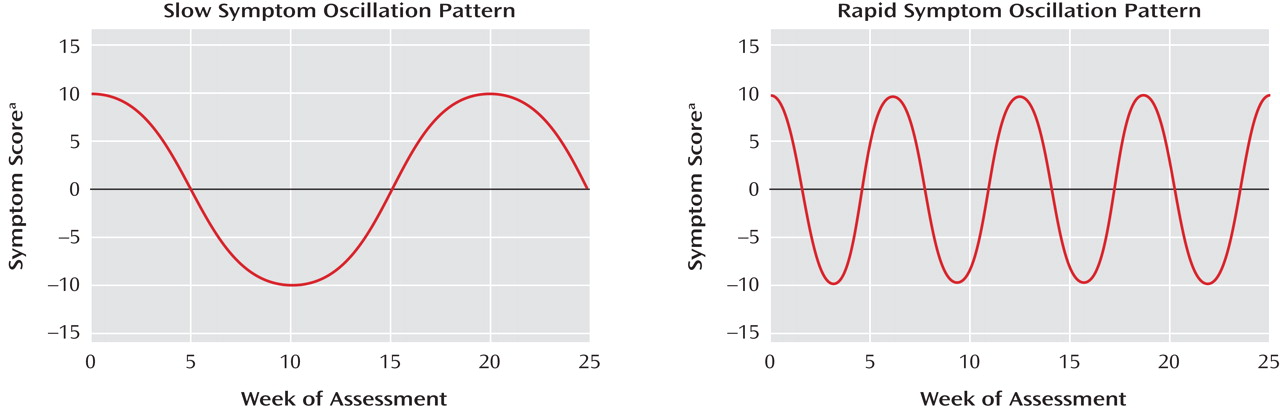

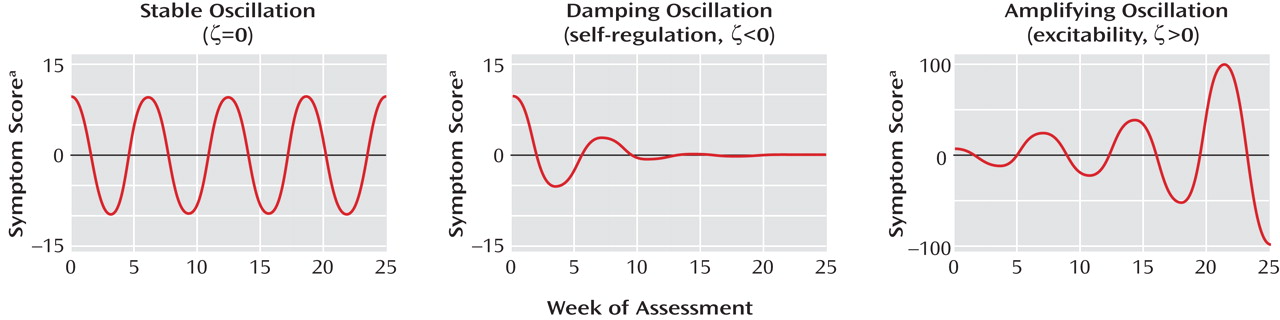

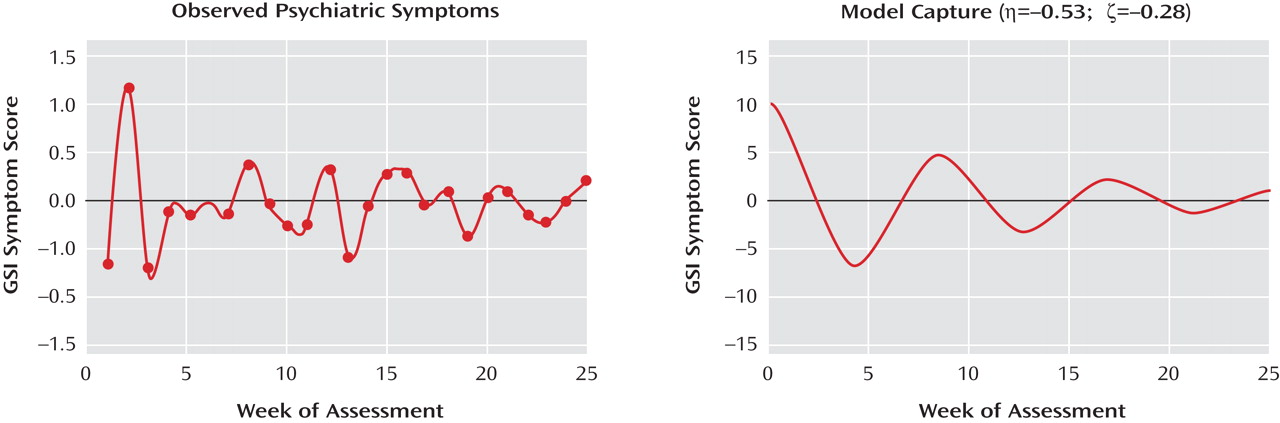

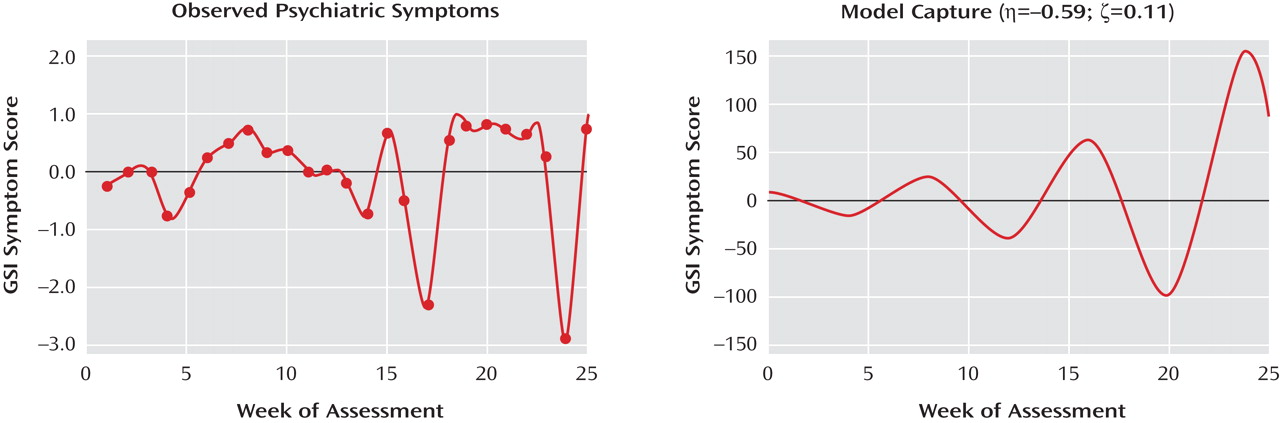

(10) . In the present study, we demonstrate how key dimensions of short-term symptom change—namely how rapidly symptoms vary (symptom oscillation) and the pattern of that oscillation (i.e., whether symptoms are amplifying versus damping over time)—can be captured using dynamical systems models. This class of models was developed to describe systems that exhibit intrinsically predictable patterns of change

(12) and also map closely to clinically relevant characteristics of symptom change

(12 –

15), including, for example, whether symptoms are “rapidly cycling,” “coming back to baseline,” or “ramping up” over time

(14,

16) .