Enduring psychiatric sequelae in children who have lost a parent have been demonstrated by retrospective, record-linkage, and prospective studies

(1 –

3) . However, relatively little is known about the time, course, and causal pathways leading to disorders in parentally bereaved children. The delineation of predictors and temporal pathways to disorders and recovery could help to clarify the boundaries of normal versus pathological bereavement and to frame targets for effective intervention.

We have previously reported that children of parents who died of suicide, accidental death, or sudden natural death had higher rates of new-onset depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) than nonbereaved comparison subjects during the first 9 months after the death, with no within-group differences attributable to cause of parental death

(4) . Significant correlates of depression, the most common new-onset condition, were degree of impairment in the surviving parent, intercurrent life events, negative child coping, and child history of a psychiatric disorder before the death.

We now report on a 21-month follow-up of this cohort in order to describe the ongoing trajectory of disorders and symptoms in the bereaved youth relative to nonbereaved comparison subjects. We hypothesized that 1) at 21 months after the death, bereaved youth would continue to show a higher prevalence and symptom severity of depression and PTSD than nonbereaved comparison subjects, 2) during the second year of follow-up, youth whose parents died by suicide would show the highest prevalence and incidence of depression, 3) predictors of depression during follow-up would include worse caregiver functioning, stressful life events, negative coping, low social support, and prior history of depression, and 4) within the bereaved group, depression would be predicted by the preceding variables, in addition to parental suicide and high baseline levels of complicated grief.

Results

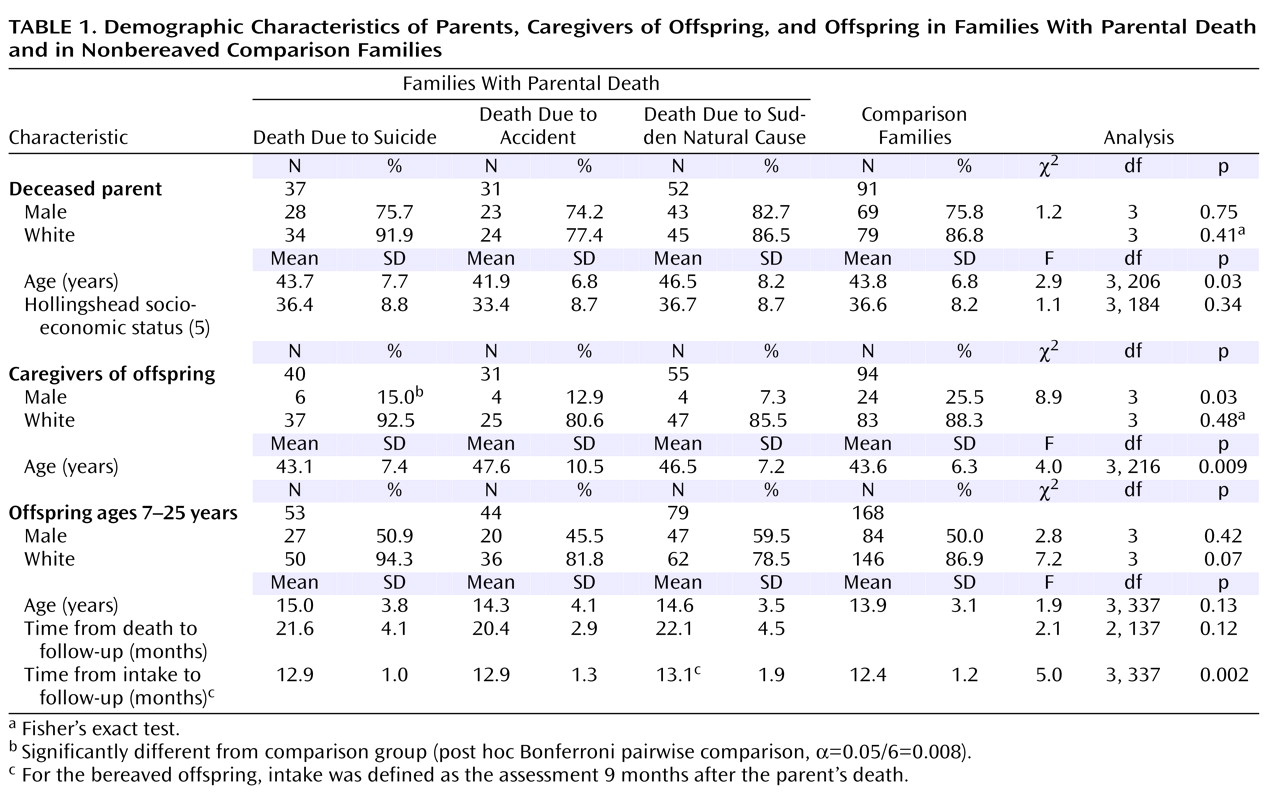

Diagnoses and Symptoms 21 Months After Parent’s Death

In relation to the nonbereaved comparison group, the total group of bereaved offspring had higher rates of major depression (10.2% versus 2.4%; p<0.007, Fisher’s exact test) and alcohol or substance abuse (4.5% versus 0.0%; p=0.008, Fisher’s exact test). As shown in

Table 2, post hoc contrasts showed that the offspring of parents who died by suicide and offspring of those who died in accidents showed higher rates of major depression than did the comparison subjects, and the children of suicide victims showed a higher rate of alcohol or substance abuse disorders than did the comparison subjects. Overall differences were found for severity of anxiety symptoms and level of functioning (

Table 2 ). Post hoc comparisons showed that anxiety was higher in youth whose parents died through accidents than in the comparison subjects and functional impairment was greater in the offspring of parents who died by accidents or by sudden natural death than in the comparison subjects. There were also group differences with respect to scores for complicated grief; the post hoc contrasts indicated that the level of complicated grief was higher in youth whose parents died through accidents than in those whose parents died by sudden natural death.

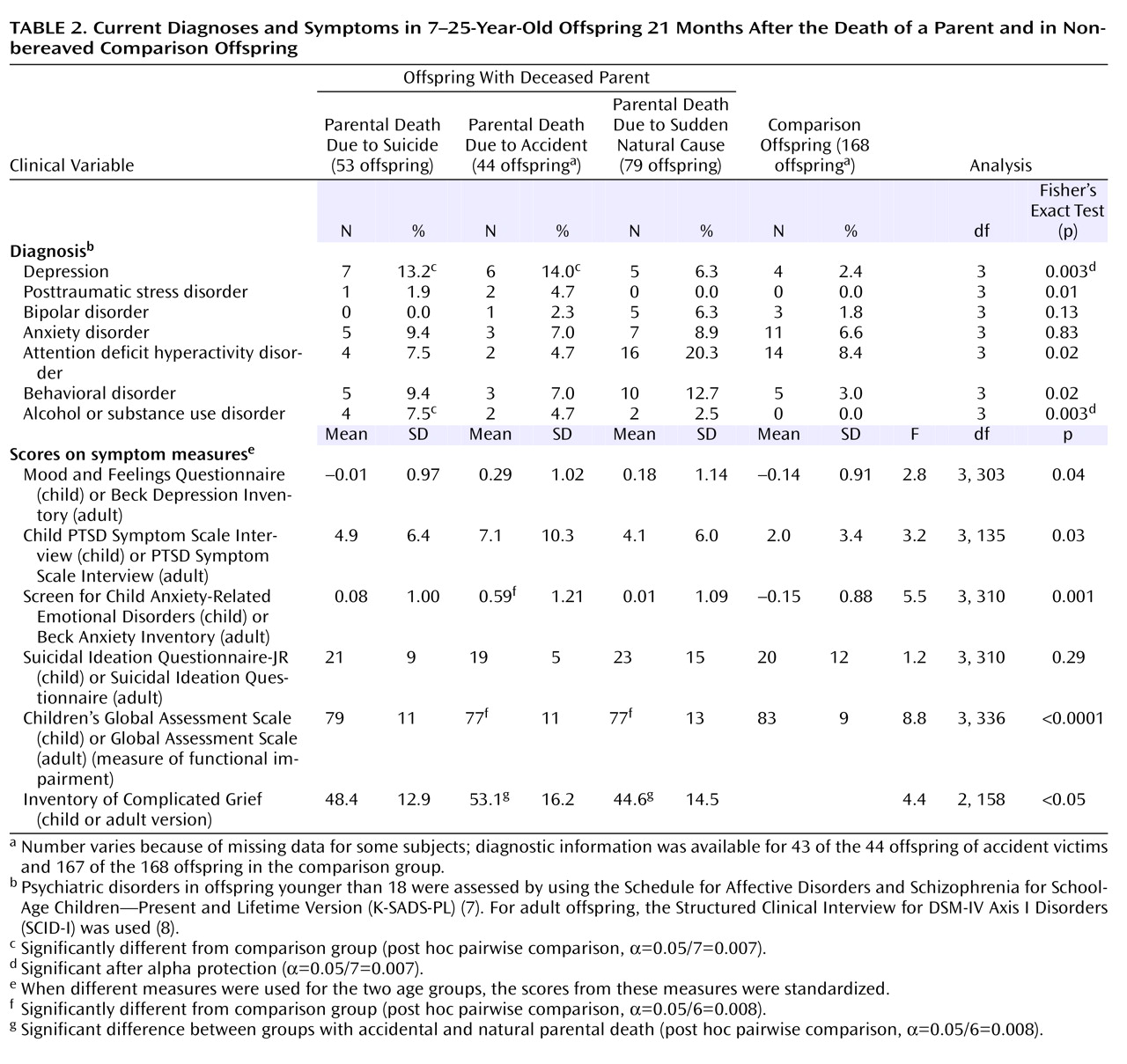

Cumulative Incidence and Course of Depression

The incidence rate ratio for depression was greater in the bereaved than in the comparison offspring; the incidence rate ratio was 2.7, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 1.6 to 4.8. There were significant differences between each of the three bereaved groups and the comparison subjects (incidence rate ratios, 2.1–3.4) but with no significant differences among the three bereaved groups (

Figure 1 ). Bereavement had a strong effect on the incidence of depression in the 9 months following the parent’s death (23.9% versus 5.4%; χ

2 =23.3, df=1, p<0.0001) but not during the subsequent year (8.5% versus 7.1%; p=0.69, Fisher’s exact test). The post hoc contrasts showed that the rate of incident depression between the 9- and 21-month assessments was higher in the offspring who lost a parent to suicide (nine of 53, 17.0%) than in those whose parents died by sudden natural death (two of 79, 2.5%) (p=0.007, Fisher’s exact test). The rates of depression remission observed in those who became depressed during the first 9 months after the death were similar in the bereaved (30 of 42, 71.4%) and comparison (six of nine, 66.7%) groups (p=1.00, Fisher’s exact test).

Cumulative Incidence and Course of PTSD

The incidence of PTSD was higher in the bereaved group than in the comparison group during the first 9 months after the death (8.5% versus 0.0%; p<0.0001, Fisher’s exact test) but not during the second year of follow-up (2.8% versus 0.0%; p=0.06, Fisher’s exact test). Of the 15 individuals with incident PTSD within 9 months of the death, all but one experienced a remission. During the second year, two of the five who experienced incident PTSD had remissions.

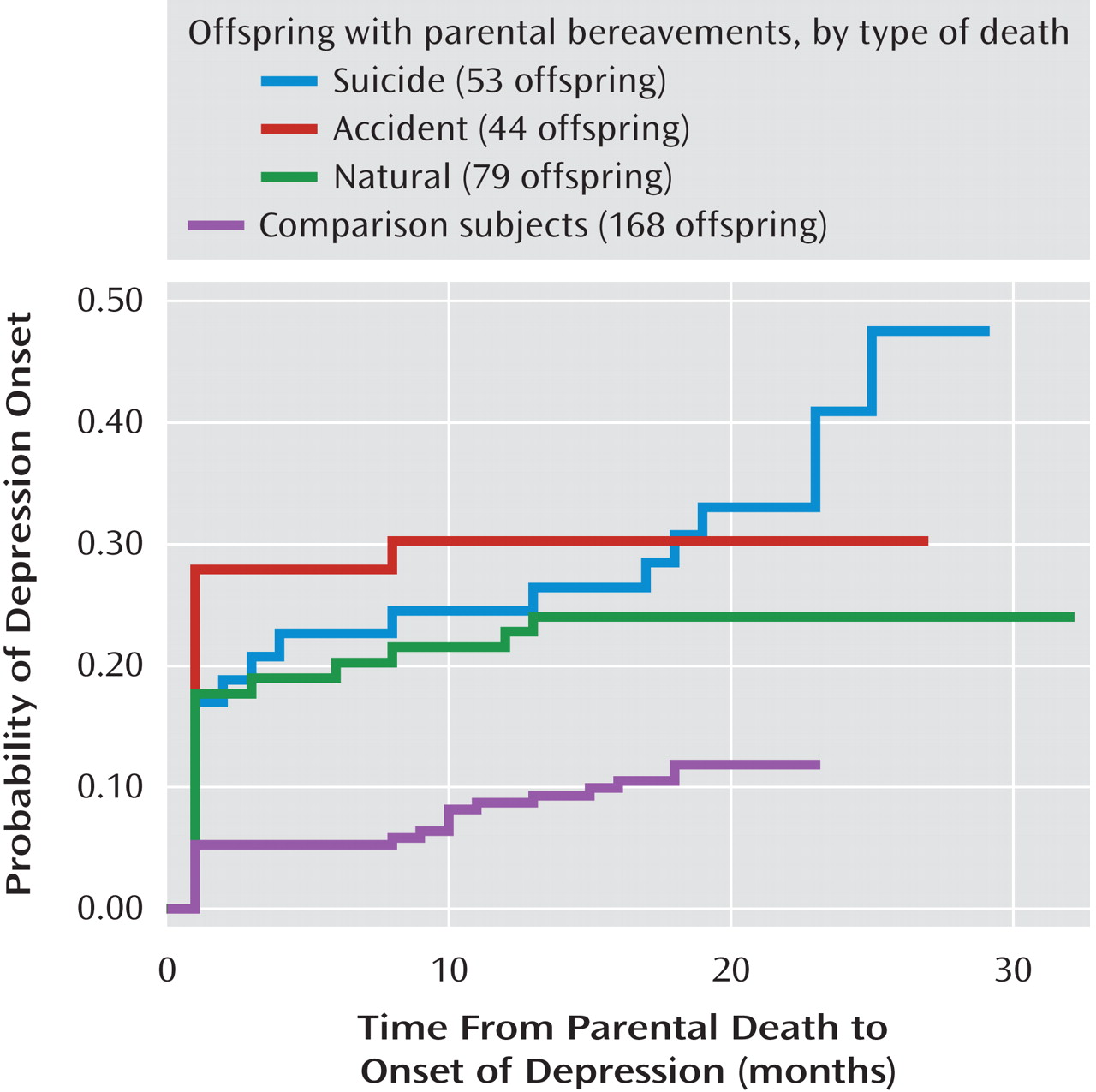

Correlates of Depressive Episode During Second Follow-Up Year

At some point during the second year of observation (from 9 to 21 months after the death), 35 offspring had a depressive episode, 22 bereaved youth and 13 comparison subjects. These depressive episodes (“follow-up depression”) included both those that were ongoing from the time of the 9-month assessment (N=8) as well as those that were incident during this time interval (N=27). Correlates of follow-up depression were female gender, older age, a previous history of anxiety or depression, and a history of sexual abuse (

Table 3 ). Characteristics assessed at the 9-month assessment that were associated with follow-up depression were greater functional impairment; higher levels of self-reported depression, anxiety, PTSD, suicidal ideation, and impulsive aggression; negative coping; greater number of stressful life events; lower family cohesion; and lower perceived social support. Many of these same variables assessed at the 21-month follow-up were also associated with a depressive episode during the follow-up period. Having had an episode of depression during the first 9 months was predictive of depression in the following year. Depression at 21 months was more likely to be a persistence or recurrence from the first observation period in the bereaved group (12 of 176, 6.8%) than in the nonbereaved offspring (three of 168, 1.8%) (p=0.03, Fisher’s exact test).

The best-fitting, most parsimonious model that predicted the occurrence of depression between 9 and 21 months included previous history of a depressive episode (odds ratio=8.6, 95% CI=1.7 to 43.8), self-reported anxiety at 9 months (odds ratio=1.6, 95% CI=1.1 to 2.4), and negative life events at 9 months (odds ratio=1.9, 95% CI=1.2 to 2.9) and 21 months (odds ratio=1.7, 95% CI=1.2 to 2.5). Compared to the other bereaved and nonbereaved groups, the offspring of parents who died sudden natural deaths had a lower risk of depression (odds ratio=0.01, 95% CI=6×10 –5 to 0.99). There was an interaction between bereavement and previous history of depression, meaning that a previous history of depression conveyed an even greater risk for subsequent depression in the nonbereaved group (odds ratio=23.5, 95% CI=1.6 to 350.7). In this regression, the diagnosis of bipolar disorder in the proband, which was an important correlate of incident depression within the first 9 months after parental loss, was associated with a threefold (odds ration=3.15, 95% CI=0.98 to 10.2) increased risk of depression, although it was not statistically significant (p=0.06).

Within the bereaved group, depression between 9 and 21 months was associated with the loss of a mother rather than a father (41.9% versus 13.7%; p=0.004, Fisher’s exact test) and a previous history of any psychiatric disorder (57.1% versus 32.9%; χ 2 =4.7, df=1, p=0.03). The risk of follow-up depression tended to be higher in those whose parent died by suicide than in those with parental bereavement due to natural death (18.9% versus 1.3%) (p=0.05, Fisher’s exact test). Higher scores for complicated grief at 9 months and lower self-esteem scores (mean=13.0, SD=5.1, versus mean=18.6, SD=7.0; t=–3.5, df=21.8, p=0.002) were associated with subsequent depression, as were a similar set of measures of self-reported symptoms and psychosocial characteristics at both 9 and 21 months, as noted already. Those who developed depression in the first 9 months after the death were more likely to have an incident depressive episode between 9 and 21 months (54.5%) than were those without depression in the first 9 months (19.6%) (χ 2 =12.9, df=1, p<0.001). Those with PTSD during the first 9 months were also more likely to develop depression during the next assessment period (18.2% versus 5.2%; p=0.05, Fisher’s exact test). Risk for depression during the second year of follow-up was also higher among bereaved offspring whose last conversation with the deceased was discordant (26.3% versus 6.1%; p=0.02, Fisher’s exact test) or who felt that others were accountable for the death (47.6% versus 21.6%; χ 2 =6.6, df=1, p=0.01).

Logistic regression identified the following as the most parsimonious, best-fitting set of predictors of depression among bereaved offspring between 9 and 21 months: baseline low self-esteem (odds ratio=1.16, 95% CI=1.05 to 1.28) and high negative coping (odds ratio=1.34, 95% CI=1.03 to 1.75) at 9 months. With the two variables in the model, parental bereavement through suicide was, as predicted, associated with a higher risk for depression between the two assessments, relative to accidents (odds ratio=2.9, 95% CI=0.83 to 10.0) and sudden natural death (odds ratio=3.5, 95% CI=0.95 to 12.8), but these findings escaped statistical significance.

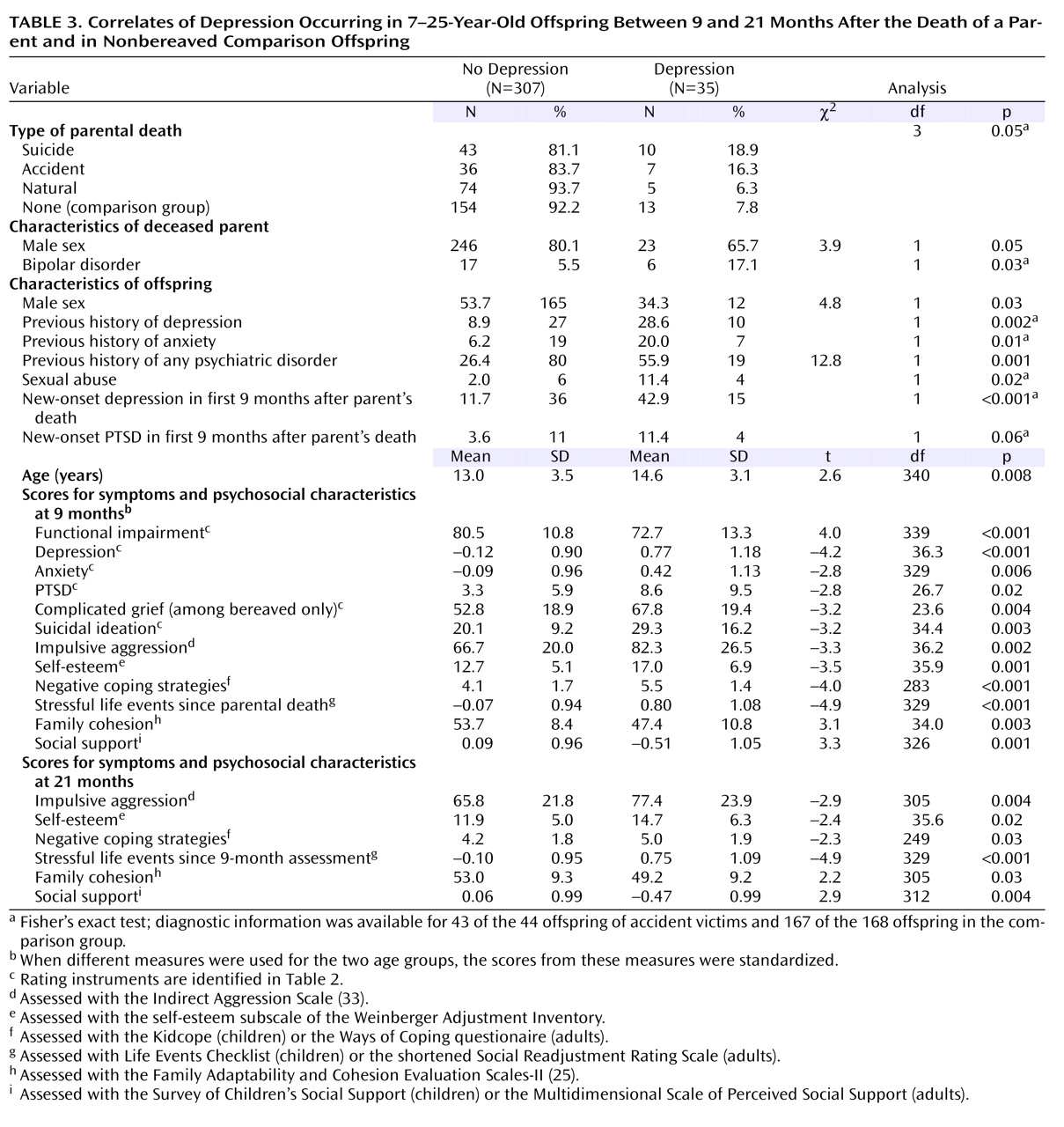

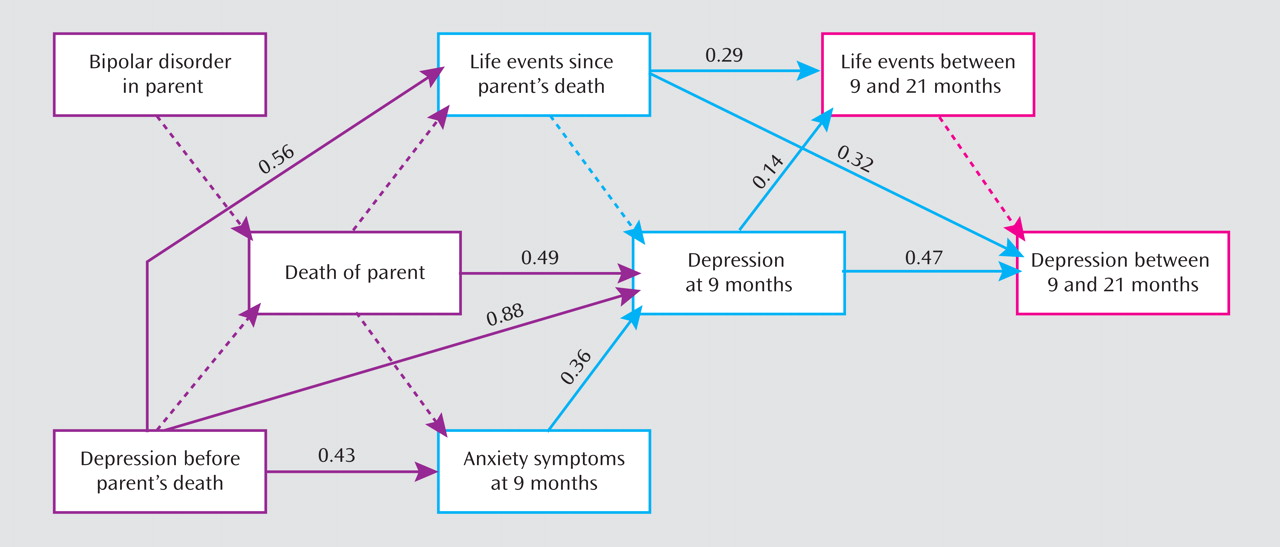

Path Analysis

A good-fitting path model predicting depression between 9 and 21 months was developed by using variables selected by logistic regression (chi-square test of model fit=10.4, df=8, p=0.24; comparative fit index=0.98; Tucker-Lewis index=0.96; root mean square residual=0.03; weighted root mean square residual=0.58). In this model, bereavement had an indirect effect on depression at 21 months, mediated by the relationship between bereavement and incident depression within the first 9 months of depression (

Figure 2 ). A previous history of depression, antedating the period of observation, was related to depression at 21 months through two pathways: 1) history of depression was related to negative life events, which in turn increased the risk of depression between 9 and 21 months, and 2) history of depression was related to a higher score for self-reported anxiety symptoms at 9 months, which was associated with incident depression at 9 months, which then increased the risk for depression during the subsequent year.

Discussion

In this longitudinal study, there were enduring effects of parental bereavement on the offspring, with higher rates of depression and alcohol or substance abuse, greater functional impairment, and higher self-reported anxiety nearly 2 years after the loss. Bereavement by accident and by suicide were associated with higher risks of depression than seen in nonbereaved comparison subjects; suicide-related bereavement was also associated with alcohol or substance abuse, and accident-related bereavement was also related to higher symptom levels. The direct effect of bereavement on incident depression and PTSD was limited to the first 9 months after the loss, except in the offspring of parents who died by suicide, who continued to have a higher incidence of depression than offspring whose parents had sudden natural deaths. During the second year of follow-up, the effect of bereavement on depression was mediated by the occurrence of new-onset depression during the first 9 months postbereavement. Within the bereaved group, depression at 21-month follow-up was predicted by parental suicide, loss of a mother, postbereavement depression, complicated grief, negative coping, low self-esteem, and blaming others for the death.

These results should be considered within the context of the strengths and limitations of this study. This is one of the largest population-based longitudinal studies of the impact of parental bereavement on children, and it is one of the few to examine the specific effects on offspring of parental death by suicide. Despite the study’s relative size, contrasts among the different causes of death can detect only relatively large effects. Also, the study group is mostly Caucasian and does not include parental homicide, thereby limiting the generalizability of these findings.

Nearly 2 years after the death, bereaved youth showed higher rates of depression and alcohol or substance abuse than comparison subjects, higher self-rated anxiety, and greater functional impairment. The main effect of bereavement on both incident depression and PTSD occurred shortly after the death, as has been reported in other studies of adolescent bereavement

(12,

34) . However, bereavement had an indirect effect on depression during the second year of follow-up, by increasing the risk of incident depression within 9 months of the loss, which increased the likelihood of depression during the next year. This pathway is attributable in part to the persistence and recurrence of these incident episodes of depression occurring shortly after the loss in the bereaved group.

Prior history of depression was related to depressive outcome at 21-month follow-up through two pathways. First, a history of depression was associated with an increased risk of negative life events, which then increased the risk of subsequent depression. Second, a history of depression was related to anxiety at 9 months, which was associated with incident depression during the first 9 months; depression in the first 9 months increased the risk of incident depression between 9 and 21 months. While a prior history of depression predicted depression at 21 months among the bereaved, it was an even stronger predictor of subsequent depression in the nonbereaved comparison subjects, which contrasts with findings in some other studies of adolescent bereavement

(12) .

As hypothesized, offspring of parents who died by suicide showed higher rates of current and incident depression from 9 to 21 months after the death, in relation to the comparison subjects and the offspring of parents who died by sudden natural death, respectively. Offspring of the suicide group also showed a higher rate of alcohol or substance abuse. However, all deleterious effects of bereavement were not attributable to suicide. Offspring of parents who died through accidents also showed higher rates of depression than comparison subjects at 21 months, had the highest scores on self-reported anxiety and complicated grief, and were more functionally impaired. Other studies have shown either no difference between youth whose parents died by suicide and those whose parents died of other causes

(35) or more behavioral or anxiety symptoms, but not depression

(36) .

The pathways and predictors of depression in this study group suggest that there may be a window of opportunity shortly after a parent’s death in which to prevent or attenuate further depressive episodes in bereaved youth. This is because the effect of bereavement on depression 21 months after the death is mediated by the occurrence of depression in the 9 months after the death. Previous intervention studies have not found a critical period during which the intervention is more effective, but these studies did not have data about prior course for participants enrolled longer after the death

(37) . However, our previous

(4) and current findings are convergent with the prevention studies of Sandler and colleagues, who have identified the critical roles of coping, self-esteem, negative life events, family cohesion, and social support in mediating long-term outcome for parentally bereaved youth

(37) .

Within the bereaved group, we found that the loss of a mother was more deleterious than the loss of a father. Although this finding did not survive multivariate analyses, it is consistent with other reports

(38,

39) . Bereaved youth who had high levels of complicated grief and those who blamed others for the death were at particularly high risk for depression at the 21-month follow-up. This finding is consistent with studies in adults showing prolonged time to recovery from depression in those with complicated grief, and it provides additional support for the existence of complicated grief in children and adolescents

(14,

40) . Interventions that target complicated grief and the placement of blame for the death on others may be useful in managing symptomatic and impaired parentally bereaved youth.

In conclusion, we have shown that there are enduring effects of parental bereavement, especially with regard to the occurrence of depression during the second year of follow-up. The offspring of parents who died by suicide showed the highest risk for subsequent depression. Since the effects of bereavement on depression in the second year were mediated by the increased risk of depression occurring shortly after the death, the best time to intervene to prevent further depression episodes may be shortly after the loss. Further follow-up of this cohort should help to address the validity and impact of complicated grief and whether individuals with a parent who dies by suicide do indeed suffer more long-term sequelae, compared to other bereaved youth.