Illicit anabolic-androgenic steroid (AAS) use represents a growing worldwide public health problem

(1,

2) . Some AAS users consume only a few courses of these drugs in a lifetime, but others progress to a maladaptive pattern of almost continuous use, despite adverse medical, psychological, and social effects

(3,

4) . In the last 20 years, accumulating animal and human studies have documented and characterized this syndrome of AAS dependence. For example, rats and mice will select AAS in conditioned place preference models

(5), and hamsters will self-administer testosterone even to the point of death

(6) . Unlike rodents, humans may initially develop a pattern of AAS dependence as a result of “muscle dysmorphia”—a form of body dysmorphic disorder characterized by preoccupation with the idea that one does not look adequately muscular

(7) . In later stages, however, AAS dependence comes to resemble classical drug dependence, with a well-defined withdrawal syndrome mediated both by neuroendocrine factors and by a variety of cortical neurotransmitter systems, especially the opioidergic system

(5,

8) . Dependence on AAS may be associated with substantial medical morbidity, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiomyopathy, and persistent hypogonadism, together with psychoactive effects, such as manic or hypomanic episodes during AAS use (sometimes associated with aggression and violence), major depressive episodes during AAS withdrawal (with occasional reported suicides), and progression to other forms of substance abuse and dependence, especially opioid dependence

(2) . The full magnitude of these risks is still unknown, because widespread AAS abuse did not spread from the athletic world to the general population until the 1980s

(2), and only now are many AAS users becoming old enough to have developed a dependence pattern with an increased risk for these adverse outcomes. Although AAS users historically have been reluctant to seek treatment

(1,

9), these adverse outcomes may now bring increasing numbers to clinical attention.

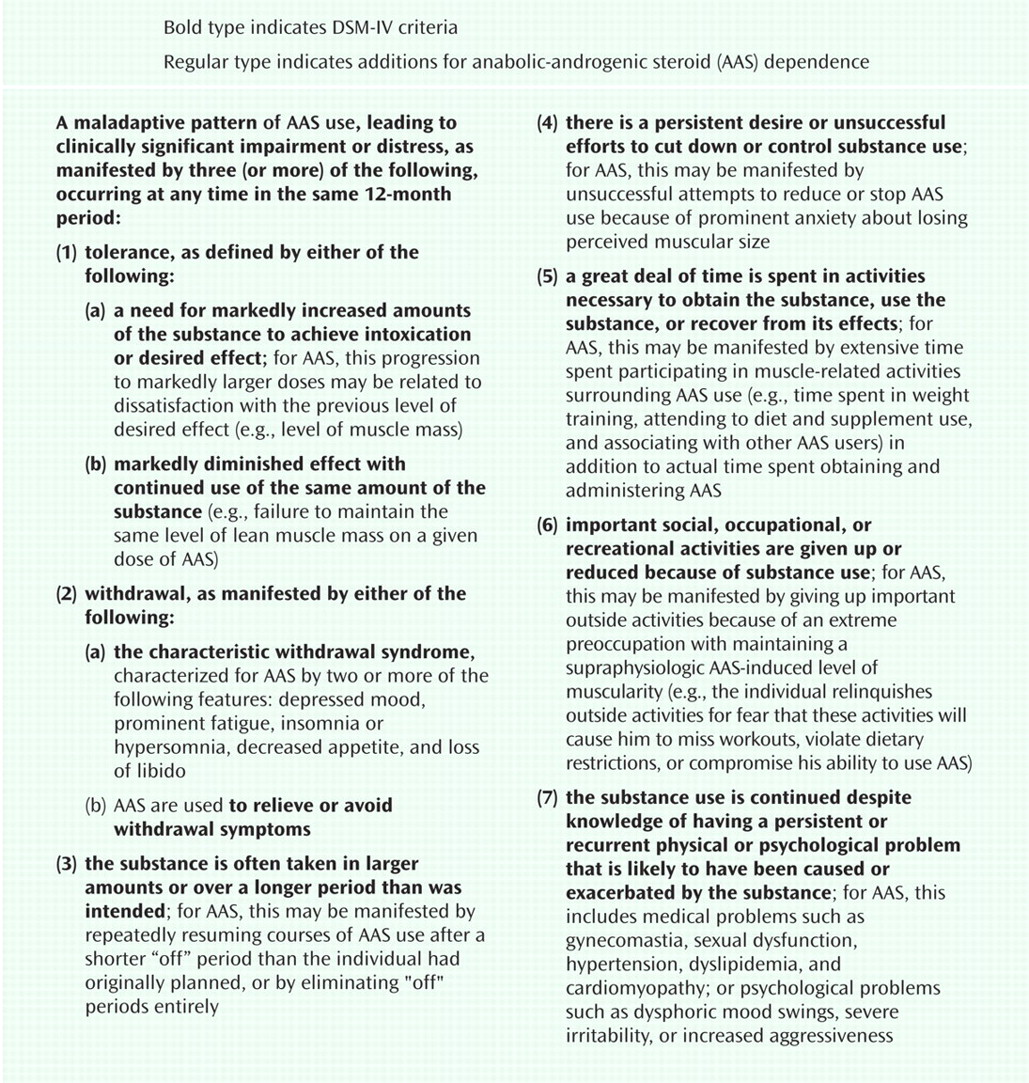

An important difference between classical drugs of abuse and AAS is that the latter are not ingested to achieve an immediate “high” of acute intoxication but, instead, are consumed over a preplanned course of many weeks to achieve a delayed reward of increased muscularity. Therefore, the existing DSM-IV criteria for substance dependence, which were designed primarily for acutely intoxicating drugs, do not apply precisely to AAS. For example, criteria such as “the substance is often taken in larger amounts...than was intended” and “important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of substance use” apply more easily to alcohol or cocaine than to AAS. But these considerations should not obscure the fact that AAS have definite psychoactive effects, including a potential for addiction, which is likely underestimated because attention has focused on the drugs’ muscle-building properties

(1) .

On the basis of the available literature

(2 –

4,

10) and clinical experience with AAS-dependent individuals, we suggest that the existing DSM criteria be adapted for diagnosing AAS dependence with only small interpretive changes (

Figure 1 ). Presently, AAS are the only major class of drugs scheduled by the Drug Enforcement Administration for which DSM-IV does not explicitly recognize a dependence syndrome

(11) ; this omission could be rectified in DSM-V by offering these proposed interpretations for AAS dependence in the substance dependence section. Alternatively, DSM-V could initially propose these criteria only for research purposes, pending further evidence of their reliability and validity. In either case, clarified criteria for AAS dependence will likely improve recognition of this diagnosis among clinicians and researchers encountering the syndrome, and they should stimulate increased attention to this emerging public health problem.