Key Clinical Characteristics

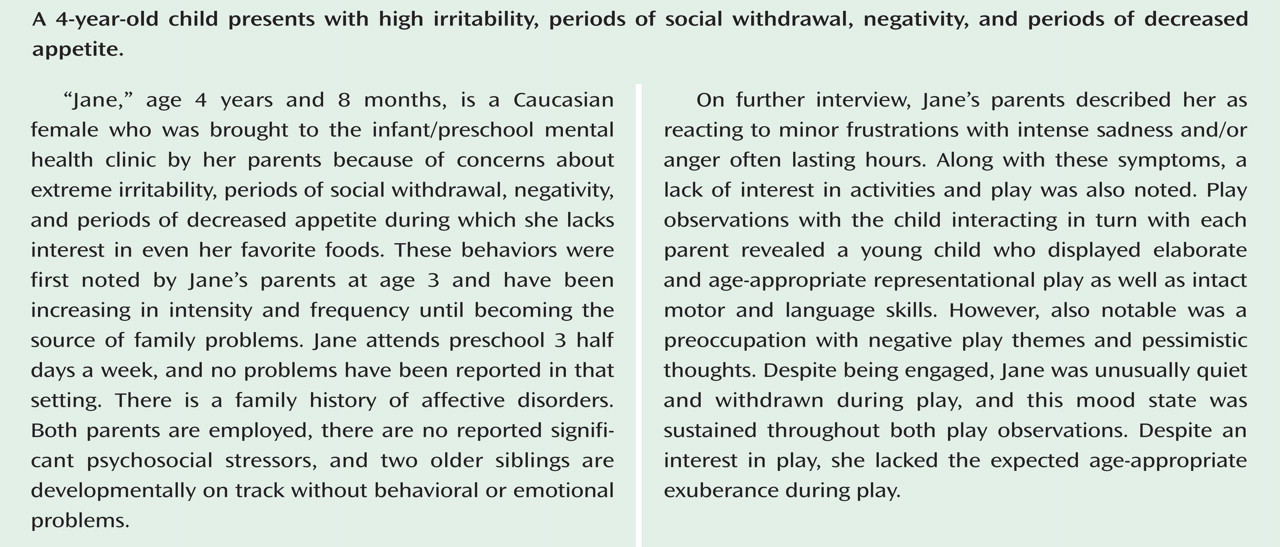

The case vignette below illustrates several clinical features typical of early childhood depression. Intense irritability is perhaps the most common symptom prompting parents to bring a young child for mental health evaluation other than disruptive behavior. While irritability is nonspecific and may be a symptom of a variety of early childhood disorders, when it presents along with social withdrawal and anhedonia and/or excessive guilt, early depression should be considered. The absence of significant developmental delay and the report that the symptoms are not impairing in a preschool setting that the child attends for short blocks of time are also common features. Data have shown that, similar to depression in older children, preschool depression is more often characterized by age-adjusted manifestations of the typical symptoms of depression than by “masked” symptoms, such as somatic complaints or aggression

(1,

2) . Notably, while irritability was added to the DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder for children based on the assumption that it may serve as a developmental proxy for sadness, there is little empirical data to support this thesis. In a sample of 75 depressed preschoolers, only five (7%) failed to meet criteria for major depression when the symptom of irritability was set aside, suggesting that irritability is not a key proxy for sadness in preschool children (J.L. Luby et al., unpublished 2008 data).

A key issue in the assessment of internalizing disorders, particularly depression, in young children is that caregivers may fail to spontaneously report symptoms (changes in play, social interest, sleep, and so on) or may unwittingly accommodate these behaviors and thereby fail to regard them as symptoms (e.g., anxious rituals, rigidities, and social withdrawal), making it incumbent on the clinician to make detailed inquiries into all aspects of a young child’s functioning.

Validation for Early Childhood Depression

The study of depression arising during the preschool period (prior to age 6) is relatively new. However, over the past decade, empirical data have become available that refute traditional developmental theory suggesting that preschool children would be developmentally too immature to experience depressive affects (see reference

3 for a review). Basic developmental studies, serving as a framework and catalyst for these clinical investigations, have also shown that preschool children are far more emotionally sophisticated than previously recognized

(4 –

8) . While some of these emotion developmental findings are new, others have been available for some time but never previously applied to clinical models of childhood affective disorders. These findings on early emotion development, obtained using narrative and observational methods, provide a key framework for studies of early childhood depression, as they establish that very young children are able to experience complex affects seen in depression, such as guilt and shame. Indeed, guilt and shame have been observed to occur more frequently in depressed than in healthy preschoolers

(9) .

Adding to early studies by Kashani and colleagues first identifying preschool depression

(10,

11), larger studies have investigated the validity of the early-onset disorder. Markers of the validity of preschool depression include findings of a specific and stable symptom constellation, biological correlates evidenced by alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (elevated stress hormone reactivity) similar to those seen in adult depression, and increased rates of affective disorders in family members of depressed preschoolers

(2,

12,

13) . These findings encompass several of the proposed markers of a valid psychiatric syndrome as proposed by Robins and Guze

(14), used in the application of the medical model to psychiatric disorders. In addition, preschool depression has been detected in four independent study samples

(2,

15 –

17) . Whether early childhood depression shows longitudinal continuity with later childhood depression remains a key empirical question. Along this line, recent longitudinal data

(18) demonstrate that preschool-onset depression shows homotypic continuity over a 2-year period and has a chronic and recurrent course continuous with and similar to that seen in school-age depression.

Treatment: Background and Progress

Very little empirical literature is available to guide treatment once the diagnosis of depression is established. Given the relatively recent scientific validation and related acceptance of preschool depression, no systematic treatment studies have yet become available. This is a particularly challenging scientific issue, as to date, effective treatments for depression during the school-age period have remained elusive. Psychotherapies known to be effective in adult and adolescent depression, in particular cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy, have been adapted for use in school-age children. While several empirical investigations of CBT for children have shown positive treatment effects, data demonstrating the efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy are currently available only for adolescents. The results of several smaller CBT trials in school-age children have been promising

(21 –

23) . However, a comprehensive meta-analysis of studies of psychotherapies for childhood depression suggests a much smaller effect size than previously reported, concluding that longer-term efficacy of CBT for school-age children has not been established

(24) . A large multisite treatment study of adolescent depression that investigated CBT and medication, independently and in combination, demonstrated promising short-term outcomes but high relapse rates

(25) . In addition, novel and highly feasible treatments for depression in school-age children, using group formats and/or behavioral activation strategies, are also undergoing testing and appear promising

(26,

27) . Given these remaining challenges in the treatment of school-age depression, no clear model for extending effective treatments to early childhood populations is yet available. Another potential area for extrapolation would be the application of prevention strategies designed for and known to be effective in older children to younger populations. Alternatively, novel approaches adapted from psychotherapies with established efficacy in treating other early childhood disorders applied to the treatment of depression may be worthwhile, and one such approach that is currently being tested is described below.

Although one study has demonstrated the efficacy of fluoxetine for the treatment of school-age depression

(28), further complicating the treatment of early childhood depression is the idea that depression in younger children is characterized by unique alterations in neurotransmitter systems. These developmental differences have been proposed as an explanation for the known lack of efficacy of tricyclic antidepressants as well as several negative studies of the newer-generation antidepressants (see reference

29 for a review). Short of a few case reports

(30,

31), no data are available on the safety or efficacy of antidepressant medication in any form of preschool psychopathology. Based on this and the finding that younger children may be at greater risk for activation from selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

(32), the use of antidepressants is not a first- or even second-line treatment for early childhood depression at this time.

Considering these findings, and balancing the need for safety and efficacy, parent-child dyadic psychotherapeutic interventions are currently recommended as the first line of treatment for early childhood depression. Dyadic approaches (defined by focus on child and caregiver together) are central to psychotherapies appropriate for young children, given the fundamental reliance of the child on the caregiver for socioemotional and adaptive functioning. Early psychotherapeutic and behavioral approaches have shown promise in the treatment of disruptive disorders in early childhood

(33 –

36) . Following these promising findings, a novel parent-child psychotherapy has been developed for the treatment of preschool depression and is currently undergoing testing. Parent Child Interaction Therapy–Emotion Development (PCIT-ED) utilizes and expands a well-validated manualized treatment (PCIT) developed by Eyberg that has proven efficacy for preschool disruptive disorders

(37) . For the treatment of mood disorders, a newly developed key module has been added that focuses on enhancing emotion development. This emotion-development module is designed to target and enhance the preschooler’s emotional developmental capacities through the use of emotion education. Perhaps most important, it also targets the child’s capacity for emotion regulation by enhancing the caregiver’s capacity to serve as an effective external emotion regulator for the child. The module is based on a model of early mood disorders that links alterations in emotion development to risk for and onset of depression

(38) . Several independent lines of empirical evidence provide support for such an emotion developmental model

(39,

40), with at least one study emphasizing the role of parental depression history and parent-child interaction in these risk trajectories

(41) . Therefore, the intervention targets the enhancement of emotional skills as well as a more adaptive pattern of emotional response to evocative events experienced in daily life.

PCIT-ED is a manualized 14-session psychotherapeutic treatment. As originally outlined by Eyberg in PCIT, the primary caregiver is key to the implementation of this treatment and serves as the “arm of the therapist.” A microphone and earbud are used during interactions with the child in session to allow the therapist, who observes through a one-way mirror, to provide in vivo coaching of the caregiver to intervene more effectively on the child’s behalf. Homework is designed to enhance skill achievement between weekly sessions. In the case of the depressed young child, enhancing positive emotion in response to incentive events and reducing negative emotion in response to frustrating or sad events are targets of treatment by coaching the parent to respond to the child during contrived (and spontaneous) in vivo experiences in session. Enhancing the child’s capacity to identify emotions in self and others is a primary goal. These therapeutic targets are based on an emotion dynamic model of depression in which the child’s capacity for emotional responses at peak intensity, but with the capacity for optimal regulation (i.e., return to euthymic baseline), is deemed key to healthy emotion development and amelioration of early mood symptoms.

A central feature of this treatment for early depression is the emphasis on the ability to experience positive affect at high intensity as well as the capacity to regulate and recover from negative affect. This is based on the hypothesis that depressed children will be less reactive to positive stimuli and more reactive to negative stimuli than healthy children. Related biases in the areas of cognitive distortion and emotional memory are well established in depressed adults and have also been detected in older depressed children

(42,

43) . The emphasis on achieving a broad emotional repertoire, an important basic developmental goal, is also central. In essence, the key emotion-development element of treatment is fundamentally developmental and has relational elements, as it identifies the caregiver’s strengths and weaknesses in serving in this capacity for the child based on their own temperament, interpersonal and caregiving relationship history, emotional maturity and, in some cases, overt psychopathology. Caregivers with affective disorders (not uncommon in this population) are referred for their own treatment. However, when affective symptoms impede their ability to participate effectively in treatment, this is also directly addressed through in vivo coaching and in individual parent sessions.

PCIT-ED is currently undergoing randomized controlled testing. In a phase I open trial, significant and robust-appearing amelioration of symptoms of depression and anxiety were observed in treated preschoolers. Testing of an adaptation of PCIT for the treatment of anxiety disorders by an independent research group is also under way, and preliminary results have shown positive treatment responses

(44) .

Early intervention targeting developmental skills during the preschool period is an area of increasing interest and promise for the treatment of early childhood mental disorders in general. Several early-intervention programs have been empirically tested and proven to successfully ameliorate preschool disruptive symptoms

(34,

36) . A prevention program designed to enhance emotion competence in high-risk preschoolers has also shown efficacy

(45) . New therapeutic modalities that adapt cognitive-behavioral approaches as well as PCIT to target early childhood anxiety show promise

(44,

46) . Intensive behavioral approaches that target social and speech development in autism have shown remarkable outcomes in subgroups of young patients

(47) .

Although it remains unclear why early interventions are effective and whether they are more effective than later intervention, several lines of developmental evidence suggest this may be the case

(48 –

51) . While there is a need for careful empirical studies of the relative efficacy and mechanisms of early intervention, the possibility of critical periods of development, based on relatively greater neuroplasticity during early childhood, is intriguing. Such processes have been demonstrated in medical disorders (e.g., strabismus) and have driven early-treatment strategies so that these windows of opportunity for more effective treatment can be captured

(52,

53) . Treatment models utilizing critical periods of neurodevelopment have unclear applicability to early-onset mood disorders; however, empirical testing is well warranted given the potential positive public health impact.