On April 1, 2008, the U.S. House of Representatives unanimously passed House Resolution 1005 supporting the month of May as borderline personality disorder awareness month. The resolution stated that “despite its prevalence, enormous public health costs, and the devastating toll it takes on individuals, families, and communities, [borderline personality disorder] only recently has begun to command the attention it requires.” House Resolution 1005, which was the outcome of public advocacy efforts, drew attention to the disproportion between the high public health significance of borderline personality disorder and the low levels of public awareness, funded research, and treatment resources associated with the disorder. A recurrent theme in this review is the persistence of borderline personality disorder as a suspect category largely neglected by psychiatric institutions, comprising a group of patients few clinicians want to treat.

The review highlights the major clinical, scientific, and public health issues, as well as some of the remarkable personalities, that have shaped the development of this diagnosis. It is necessarily selective. It is organized chronologically, beginning with the period before the diagnosis was used clinically and then dividing the subsequent period somewhat arbitrarily into decade-long intervals. This approach allows the review of the trials and tribulations of borderline personality disorder to proceed within the framework of the changes that were concurrently transforming psychiatry.

Before 1970—From Untreatable Patients to Personality Organization: “A Psychoanalytic Colloquialism”

The identification of patients as “borderline” first arose in an era when the psychoanalytic paradigm dominated psychiatry and our classification system was primitive. At that time classification was tied to analyzability: patients with neuroses were considered analyzable—and therefore treatable—and those with psychoses were considered not analyzable—and therefore untreatable.

The psychiatrists most responsible for introducing the label “borderline” were Stern

(1) and Knight

(2) . By identifying the tendency of certain patients to regress into “borderline schizophrenia” mental states in unstructured situations, these authors gave initial clinical meaning to the borderline construct. The primary category to which these patients were “borderline” was schizophrenia

(3 –

7) . Still, until the 1970s the term “borderline” remained a rarely and inconsistently used “colloquialism within the psychoanalytic fraternity”

(8) .

The construct took its next major step forward in 1967, when Kernberg

(9), a psychoanalyst concerned with the boundaries of analyzability, defined borderline as a middle level of personality organization bounded on one side by sicker patients who had psychotic personality organization and on the other by those who were healthier and had neurotic personality organization. As such,

borderline personality organization was a broad form of psychopathology defined by primitive defenses (splitting, projective identification), identity diffusion, and lapses in reality testing

(9) . Kernberg then went on to suggest that these patients could be successfully treated with psychoanalytic psychotherapy

(10) .

Beyond the substance of Kernberg’s contributions, their significant impact must be appreciated in part as the product of his authoritative Old-World style and his tireless campaigning on their behalf. He, and to a lesser extent Masterson

(11), who highlighted abandonment issues and poor early parenting, fueled the enthusiastic pursuit of ambitious long-term intensive psychoanalytic psychotherapies for these patients.

Even as this therapeutic optimism was swelling, Klein

(12) voiced a cynical counterpoint: “Analysts’ progressive disillusionment with their ability to make permanent change in nonpsychotic patients has been masked by terminological revision. The diagnosis of

borderline disorder preserves intact the belief that classical psychoanalysis is the uniformly effective treatment of choice for neurosis, since failures occur only with the borderline patients” (p. 366).

Despite the doubts about this diagnosis’s parentage, important contributions to the borderline construct from these early psychoanalytic observations have endured, among them recognition of these patients’ “stable instability”

(13) ; their desperate need to attach to others as transitional objects

(14) ; their unstable, often distorted sense of self and others; their reliance on splitting; and their abandonment fears.

1970–1980—From Personality Organization to Syndrome: “An Adjective in Search of a Noun”

In the decade after “borderline” achieved the status of a colloquialism, the advent of descriptive psychiatry and psychopharmacology brought significant changes to psychiatry. The initial effort to describe borderline patients was made by Grinker, an early and powerful advocate of empiricism, and his colleagues in a seminal book entitled

The Borderline Syndrome (15) . This development set the stage for the publication of a review of this syndrome’s place within the context of a broader literature in a paper entitled “Defining Borderline Patients”

(16) and for the borderline syndrome to become reliably assessable with discriminating criteria

(17) . Soon afterward, it entered DSM-III

(18) as “borderline personality disorder.”

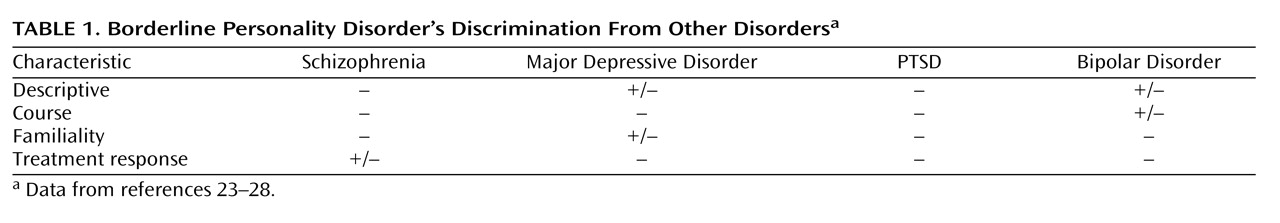

Borderline personality disorder was official, but what was it? Even before its inclusion in DSM, it had become clear that the disorder was not related to schizophrenia, and the inclusion in DSM-III of another new category, schizotypal personality disorder, finalized this cleavage

(19,

20) . Even without that, the distinctive phenomenology of borderline personality disorder made a spectrum relationship with schizophrenia unlikely. Borderline patients were interpersonally needy, very emotional, and with the exception of occasional lapses in reality testing, they were definitely not psychotic (

Table 1 ). What was also apparent was that they were “difficult” patients and had considerable suicidal risk. Klein

(21) described them as “fickle, egocentric, irresponsible, love-intoxicated.” Houck

(22) found that they were “intractable, unruly” patients who used hospitals to escape from responsibilities. Thus, these patients attracted pejorative descriptions that discouraged charitable understanding.

Given the high levels of comorbid depression in “borderline” patients, some clinicians felt that they had an atypical form of depression

(8,

29 –

31) . Akiskal

(32) famously wrote that “borderline was an adjective in search of a noun”—and at that time, in many people’s minds, that noun was clearly “depression.” Others, echoing Klein’s earlier cynicism

(12) about the origins of this disorder, felt that borderline personality disorder had been included in DSM-III simply as a conciliatory gesture intended to placate the psychoanalytic plurality, many of whom were opposed to DSM-III’s operationalization of psychiatric diagnoses.

During the 1970s, the literature on treatment for borderline personality disorder was almost exclusively about psychoanalytic psychotherapy. Numerous conferences on psychoanalytic therapy for borderline personality disorder were held, drawing large audiences. The featured speakers all achieved local, regional, or national recognition for what was considered at that time to be their heroic tolerance and remarkable skills

(10,

11,

33 –

38) . The subsequent flood of books on the disorder (

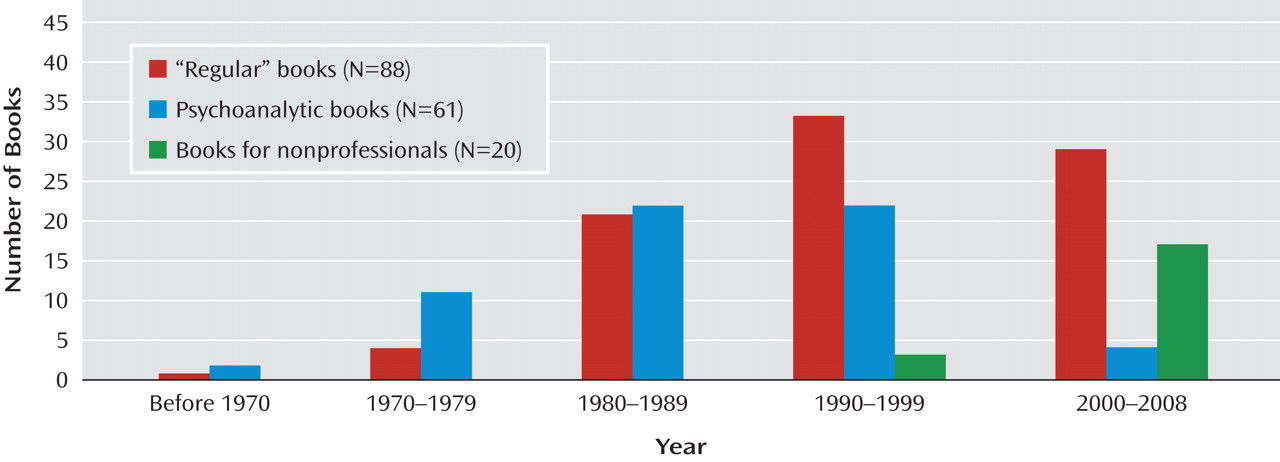

Figure 1 ) provided compelling accounts of the many serious problems encountered during these therapies, among which were the signal problems of “countertransference hatred”

(39) and “negative therapeutic reactions”

(10,

40) . Kernberg

(40) wrote that negative therapeutic reactions were common and that they derived from the borderline patient’s “1) unconscious sense of guilt (as in masochistic character structures); 2) the need to destroy what is received from the therapist because of unconscious envy …; and 3) the need to destroy the therapist as a good object because of the patient’s unconscious identification with a primitive and sadistic object” (p. 288). In retrospect, it is notable how the failures of psychoanalytic therapies were explained solely by the borderline patient’s pernicious motivations.

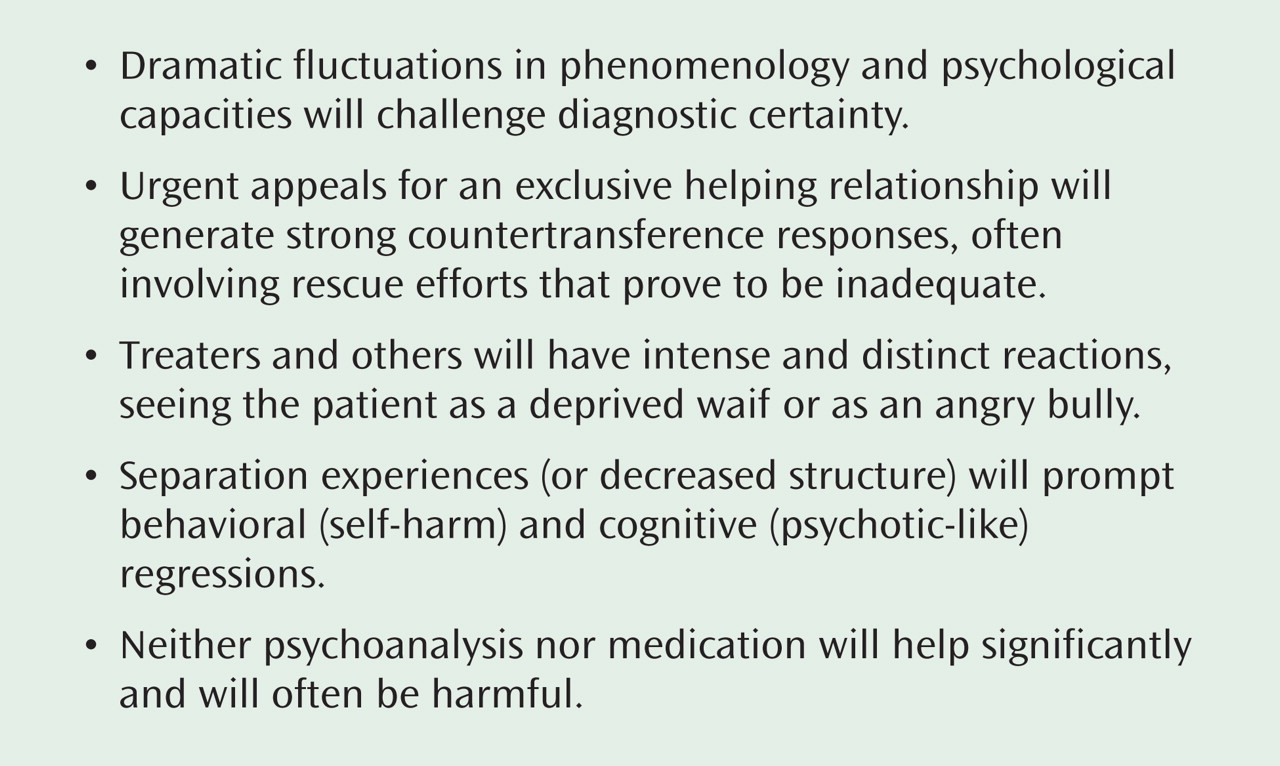

Thus, by 1980, when borderline personality disorder officially entered the DSM classification system, its validity rested primarily and still quite precariously on its clinical utility, and specifically on the ability of the diagnosis to predict a set of clinical dilemmas that were more or less specific to these patients (

Figure 2 ).

1980–1990—From Syndrome to Personality Disorder: “Wisdom Is Never Calling a Patient Borderline”

During the 1980s, biological psychiatry came to the fore and the recession of psychoanalysis began. After DSM-III defined many disorders with specific and measurable criteria, their validity was now being tested using standards set forth by Robins and Guze

(41) . This meant that the validity of borderline personality disorder, like other diagnostic syndromes, was measured via examinations for discriminating descriptors, familiality, longitudinal course, treatment response, and biological markers. The systematic examination of these areas was carried out in numerous clinical research projects on borderline personality disorder. Until 1980, fewer than 15 research reports on borderline personality disorder had been published; in the decade from 1980 to 1990, more than 275 appeared. With only one exception, these projects were conducted without federal funding.

This research showed that the borderline personality disorder syndrome was an internally consistent, coherent syndrome

(42,

43) with a course that differed from those of schizophrenia and major depression

(44 –

46) . It also showed that the syndrome was familial and that the prevalence of schizophrenia and depression was not increased in the families of borderline patients

(44,

47,

48) . The decade’s research also indicated that borderline personality disorder had modest and inconsistent responses to multiple classes of medications

(49 –

51) . One conclusion from this considerable body of clinical research was that borderline personality disorder was not simply a variation of—and was probably not closely related to—depression

(23,

52) (

Table 1 ).

The research drew attention to a previously unrecognized diagnostic interface—that with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Here, the differential diagnostic issues were based less on descriptive overlaps than on etiologic considerations. Studies of childhood physical and sexual abuse showed that there were reports of abuse in the histories of 70% of borderline personality disorder patients

(53) . This observation occurred at the same time that feminist concerns were raised about DSM-III diagnoses, including borderline personality disorder, that pathologized women or that implicitly blamed victims. Feminist clinicians suggested that descriptions of borderline psychopathology were fueled by men’s anger

(54) and that men’s use of this diagnosis for female patients reflected their negative gender biases

(55) . Herman wrote that the borderline syndrome was a “disguised presentation hiding underlying PTSD”

(53) .

The high frequency of early dropouts from psychoanalytic therapy was now well documented

(56 –

58), as was the infrequency of success with this therapy

(58 –

60) . The harm of neutrality, passivity, poor maintenance of boundaries, and countertransference enactment had become clearer, and out of the crucible of popular debates between Kernberg and other analysts (such as Adler

[35] and Kohut [

61,

62 ]) and relational psychologists (such as Jordan et al.

[63] ), the essential role of empathy and support became more widely appreciated.

Thus, the emerging trauma data and the feminist concerns about the borderline label were joined by the ever-growing chronicle of the problems borderline patients allegedly created within psychoanalytic therapies to consolidate a highly pejorative meaning for the borderline diagnosis. From this confluence, Vaillant wrote that “the beginning of wisdom is never calling a patient borderline”

(64) .

By this time, sufficient clinical wisdom had accumulated that while we may not have become clear about what we should do, we had learned a lot about what

not to do. For example, hospitals knew that borderline patients were not simply feigning symptoms to get admitted; rather, the symptoms were real, but they remitted as a result of the hospital’s “holding” and supportive functions. Indeed, borderline patients’ changing phenomenology could be made coherent by appreciating whether they felt “held” (depressed, cooperative), rejected (angry, self-destructive), or alone (impulsive, brief psychotic experiences)

(65) . It was also becoming clearer that nonpsychoanalytic modalities, including group and family therapy and medications, could often be helpful. Thus, the hopes for curative changes that had previously propelled psychoanalytic therapies were quietly being replaced by more pragmatic multimodel approaches that had more modest rehabilitative goals

(65 –

71) .

1990–2000—From Unwanted Personality Disorder to Disorder-Specific Treatability: “Would the Patient Be Borderline If She Remitted From a Medication?”

In the 1990s, DSM-IV was published (with only modest changes in the definition of borderline personality disorder) and the biological paradigm had come to dominate psychiatry. During one DSM-IV meeting a new question about borderline personality disorder’s diagnostic integrity was raised: “Would the patient be borderline if she remitted from a medication?”

(72) . This was not an easy question to answer. Indeed, borderline personality disorder’s validity was—and still remains—suspect because it has neither a specific pharmacotherapy nor a unifying neurobiological organization from which biological psychiatry can find purchase.

Against this backdrop Siever and Davis

(73) proposed two psychobiological dispositions,

affective dysregulation (with hyperresponsivity of the noradrenergic system) and

behavioral dyscontrol (with reduced serotonergic modulation), which provided a much-needed conceptual and scientific structure for understanding the origins of borderline personality disorder as well as a way to explain borderline personality disorder’s comorbidities and its spectrum relationships with other disorders. On this base, good arguments could be built for viewing borderline personality disorder primarily as an impulse spectrum disorder

(74) or an emotional (affective) dysregulation disorder

(75,

76) .

By this time, the cogent considerations about the etiological overlap between borderline personality disorder and PTSD had informed the borderline construct and had usefully shaped its boundaries

(24) . Among the clarifying findings were that borderline personality disorder has about 30% comorbidity with PTSD

(77), that borderline personality disorder often develops without a history of significant trauma

(78), that childhood abuse and trauma predispose to many other psychiatric disorders

(79,

80), and that while exploratory/expressive therapies are even more contraindicated for PTSD than for borderline personality disorder, treating borderline patients as victims of abuse usually made them worse

(81) . A subsequent group of studies has now confirmed that while childhood trauma, especially sexual abuse, is related to borderline personality disorder, a history of such trauma is unnecessary and usually does not account for much of the etiological variance

(82 –

84) .

The primary differential diagnostic issue had now become bipolar disorder. There was a substantial overlap in the underlying constructs of the two disorders as identified by Siever and Davis’s

(73) psychobiological dispositions and in their phenomenology, that is, impulsive/behavioral dyscontrol and affective/emotional instability. Moreover, the bipolar construct was expanding to include spectrum variants—most significantly, bipolar II disorder, for which mania was not required

(85) . While the response of borderline personality disorder to mood stabilizers was unimpressive

(73), the disorder’s persisting lack of any distinctive neurobiological base made it an obvious candidate for inclusion in bipolar disorder’s growing spectrum.

Even as these propositions and questions about borderline personality disorder’s biological integrity were gaining attention, the borderline construct was independently receiving creative and groundbreaking advances with respect to the psychosocial aspects of its development and treatment. From England, Peter Fonagy, a Hungarian-born psychologist and psychoanalyst armed with both his skills as a developmental researcher and his contagious energy, enthusiasm, and creativity, introduced studies of early child development and the vicissitudes of caretaking that he postulated set the stage for later development of borderline personality disorder. Beginning with studies of attachment

(86,

87) and building on earlier work by Winnicott

(88) and Bowlby

(89), Fonagy postulated that caretakers’ failure to accurately mirror a child’s mental states was responsible for establishing handicaps in knowing one’s self and in empathizing with others—an inability to

mentalize that made the child vulnerable to borderline personality disorder.

In this context, the first major stimulus to therapeutics since the psychoanalytic therapy initiative of the 1970s arrived from an unexpected source: dialectical behavior therapy was introduced by Linehan

(90), a self-described “radical behaviorist.” Dialectical behavior therapy was a carefully manualized 1-year outpatient therapy combining well-integrated group and individual therapy components. While targeting the borderline patient’s pattern of self-harm and suicidality, its benefits also extended to less utilization of medication and hospitalization

(91) . Among the innovative departures from prior therapies were dialectical behavior therapy’s insistence on split treatment and on identification of treatment goals; its emphasis on validation, skill-building, and here-and-now interventions; its provision of around-the-clock availability; and its definition of the role of the therapist as coach. As important as its empirical support was, and as innovative and learnable as dialectical behavior therapy itself was, one could not have anticipated its impact without appreciating Linehan’s personal role. She was bold, charismatic, and plainspoken. She openly challenged the claims of a psychoanalytic tradition and all other non-empirically based therapies. She inspired a new generation of zealously dedicated—and empirically buttressed—much more effective psychotherapists. Moreover, she introduced a borderline personality disorder-specific therapy that, because it was psychosocial, unwittingly offered an unexpected alternative to the reliance on medication response for satisfying the Robins and Guze

(41) validation standard of discriminating treatment response.

Eight years later, a second treatment specifically designed for borderline personality disorder was also shown to be effective. “Mentalization-based treatment” was derived from Fonagy’s developmental research and established its efficacy in an English partial hospitalization program

(92) . It was designed to correct the borderline patient’s underlying handicaps in mentalizing by adopting a noninterpretive, “not-knowing,” inquisitive stance intended to facilitate the accurate recognition and acceptance of one’s own and others’ mental states (including the therapist’s).

2000–2009—Borderline Personality Disorder: “A Good-Prognosis Brain Disease”?

The current decade has been associated with a search for the underlying etiological bases for psychiatric disorders. This reflects both a growing impatience with the extensive comorbidities in the current classification system and an excitement about the newly available neurobiological and genetic technologies.

Beginning with the stimulus given by several parent advocacy groups (most notably, the National Education Alliance for Borderline Personality Disorder, and most conspicuously, the indomitable and ubiquitous Valerie Porr) and by the establishment of the Borderline Personality Disorder Research Foundation by a bereaved Swiss family, this decade has seen the adoption of borderline personality disorder by major mental health organizations, such as the National Alliance of Mental Illness, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and, as noted at the beginning of this article, even the U.S. Congress. In this context, borderline personality disorder seems to have achieved a new legitimacy, at least as a subject for scientific study and for public awareness. Why has this occurred and what does it mean?

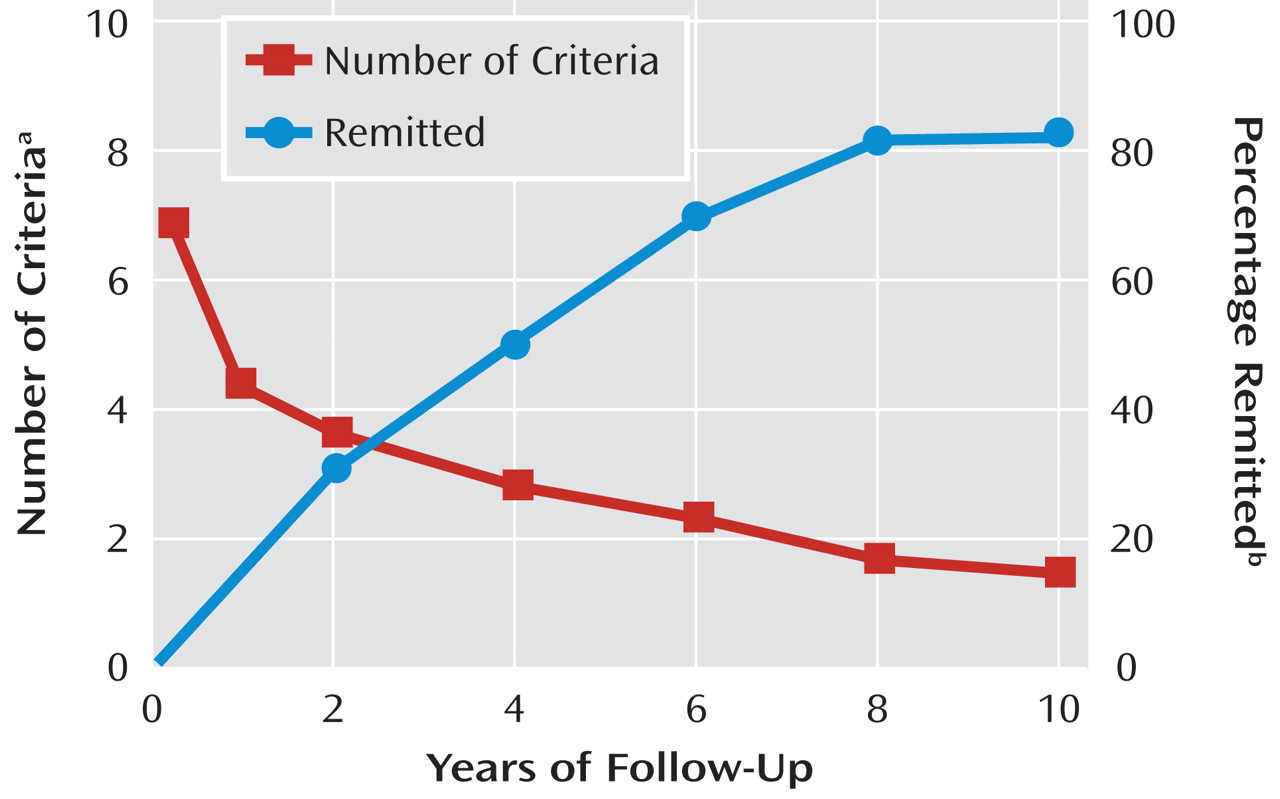

Two major findings have greatly affected the borderline construct, one showing that the disorder is significantly heritable and the other that it has an unexpectedly good prognosis. The confluence of these findings is all the more significant because together they seem to defy the expectation that heritable disorders should be among the least changeable. Torgersen and colleagues’

(93) finding of a 68% heritability abruptly invalidated the many theories about borderline personality disorder’s etiology that had focused exclusively on environmental causes. It established borderline personality disorder’s credentials as a “brain disease.”

Signaling the potential yield of the still very limited NIMH-funded research, this decade bore the fruits of two NIMH-funded longitudinal studies, the McLean Study of Adult Development

(94) and the Collaborative Longitudinal Study of Personality Disorders

(53) . These studies showed that borderline personality disorder has an unexpectedly good course (

Figure 3 ). After completing her seminal long-term follow-up reports

(95,

96), Zanarini even began to call borderline personality disorder “the good-prognosis diagnosis.” This fact offered enormous encouragement to patients with the disorder even as it raised questions about how those of us in the mental health fields could have been so mistaken. When this finding is combined with the evidence of heritability, it is clear that the DSM criteria are epiphenomena.

In 2001, despite the relative absence of an empirical basis, APA prepared guidelines for the treatment of borderline personality disorder

(97) . This was done because, as noted earlier, we now knew a lot about what

not to do. The guidelines retained a primary role for psychotherapy, but they emphasized the need to enroll patients as collaborators, the need for a primary (i.e., administratively responsible) clinician, and the value of psychoeducation, family involvement, and the use of an algorithm for medications

(98) .

Even as the APA guidelines retained a primary role for individual psychotherapy, the role of psychoanalytic psychotherapy and the literature about it had seriously declined (see

Figure 1 ). In this decade only four new books on psychoanalytic therapy for borderline personality disorder were published, and three of them were treatment manuals. Most notably these included the manualization of a revised version of Kernberg’s original psychoanalytic therapy, transference-based psychotherapy

(99) . In combination with the earlier pioneering development of mentalization-based therapy, the empirical validation of transference-based psychotherapy’s effectiveness

(100) revitalized the relevance of psychoanalytic contributions to the treatment of borderline personality disorder.

The Present—Awareness: “Borderline Personality Disorder Is to Psychiatry What Psychiatry Is to Medicine”

House Resolution 1005 states that “it is essential to increase awareness of borderline personality disorder among people suffering from this disorder, their families, mental health professionals, and the general public by promoting education, research, funding, early detection, and effective treatments.” Borderline personality disorder remains terribly and unfairly stigmatized. Most mental health professionals want to avoid—or actively dislike—borderline patients (B.M. Pfohl et al., May 1999 data from unpublished survey). Borderline personality disorder remains far behind other major psychiatric disorders in awareness and research. The difference between its reported prevalences in clinical settings (15%–25%)

(28) and in the community (1.4%–5.9%)

(101,

102) indicates that a large number of people with the disorder are undiagnosed and untreated. Research on the disorder receives a total of only about $6 million annually in NIMH funds, less than 2% of the amount allocated to research on schizophrenia (which has a prevalence of 0.4%)

(103) and less than 6% of that for bipolar disorder (which has a prevalence of 1.6%)

(104) . Despite the significant impact of borderline personality disorder on the course and treatment of anxiety disorders

(105) and mood disorders

(106), psychiatric research on these other disorders often fails even to document its co-occurrence.

Research on borderline personality disorder suffers from a lack of young investigators. Most of those who put this diagnosis on the map are approaching retirement, and few of them have the research credentials or funding to nurture a next generation. A growing number of empirically validated treatments for borderline personality disorder exist, but they remain largely unavailable or, when available, are often not reimbursed. More remarkable is that borderline personality disorder still lacks a standing presence in psychiatric training curricula. Appropriate teaching—both academic and clinical—for residents is nonexistent in all but a few institutions.

Figure 4 identifies some of the future directions for borderline personality disorder in light of these facts.

The escalating number of books written for nonprofessionals (see

Figure 1 ) bears witness to the devastating toll the disorder takes on others. Still unknown are the public health costs of this disorder, but given borderline patients’ heavy utilization of psychiatric services; medical complications; involvement in divorce, libel, and childrearing lawsuits; and violence and sexual indiscretions, the costs can be expected to be tremendous. Also unknown, despite significant advances

(107 –

109), is borderline personality disorder’s core psychopathology and its related neurobiology. While spectrum relationships with bipolar disorder and antisocial personality disorder

(110) seem most significant, borderline personality disorder’s defining clinical features remain interpersonal

(111) .

With the development of DSM-V under way, borderline personality disorder’s internal coherence and integrity stand on firm ground

(112 –

115), but questions can be expected about whether the label “borderline” should be retained, about whether the diagnosis belongs on axis I instead of axis II, and about whether the diagnosis should be given to adolescents. I believe the term “borderline” has earned honorific status by virtue of its familiarity. As highlighted in this review, it accurately signifies borderline personality disorder’s unclear boundaries while reminding us of an unwanted truth, namely, that psychiatric disorders, like other medical conditions, are heterogeneous and have flexible boundaries. It should not be scapegoated because of this. With respect to the question of whether it should be on axis I or axis II, it belongs on axis I to signify its severity, its morbidity, and its unstable course. But it belongs there too to prioritize its usage and to underscore the need for its treatment to be reimbursed. Use of the borderline diagnosis clearly should be extended to adolescents; its clinical usage in this group is already extensive, its internal coherence and stability are established, and it predicts adult dysfunction as well as adult borderline personality disorder

(116) .

In modern psychiatry, borderline personality disorder has become the major container for sustaining the relevance of the mind, an arena that has been endangered by our growing biological knowledge. For example, when a borderline patient cuts him- or herself, the behavior can be understood as providing relief by redirecting intolerable and inchoate psychic pain into physical pain with both a welcome focus of attention and a welcome release of neurohormones. This behavior can just as aptly be considered a breakdown in the ability to mentalize, that is, to keep in mind both the feelings about oneself and another. Such conceptualizations still need to recognize that the intensity or intolerance of the affect has a heritable base—as does, probably, the violent and impulsive cutting behavior itself—and that the patient has a special sensitivity to rejection. But so much is lost if in addition to these explanatory conceptions the cutting is not also seen as an act of self-punishment related to an overly harsh self-judgment reflecting a long-standing perception of “badness.” It is the latter translation of the event that reintroduces the mind. When that sense of badness is further understood as having been derived in part from a family context with much criticism and little nurturance, we begin to give color and distinction to the environmental experiences that account for much of the etiological variance behind the patient’s cuttings. We also begin to recognize a unique personal narrative that allows the person’s life experience to be meaningful and unique and for the person to feel understandable and acceptable—and not as bad as he or she thought.

At this time, borderline personality disorder is the only major psychiatric disorder for which psychosocial interventions remain the primary treatment. Residents who go into psychiatry with an interest in personal involvements, in seeing themselves in their patient’s experiences and their selves as therapeutic tools, now can find few other places in psychiatry to actualize these aspirations. Residents and other mental health professionals who make a serious investment in treating patients with borderline personality disorder can expect to become proud of their professional skills and of their personal growth in tolerance and empathy and to experience a highly personal, deeply appreciated, life-changing role for their patients.