Predictions about the epidemic nature of both diabetes mellitus and depression during the first quarter of the 21st century are a matter of concern (

1,

2), and negative effects in cases of comorbidity of these two conditions have been reported (

3). In this context, hypotheses regarding the possibility that depression may eventually produce diabetes mellitus have recently been tested in longitudinal studies. In a meta-analysis, Mezuk et al. (

4) identified 13 such studies and concluded that depressed individuals have a 60% increased risk of developing diabetes mellitus (

4). However, most of these studies used rather weak methods to document depression (

5), such as self-reports or general physicians' diagnoses, and therefore do not provide enough information on subjects with clinically significant depression (

6). Of interest, in a previous meta-analysis, Knol et al. (

7) found that only the study conducted by Eaton et al. (

8) used formal diagnostic criteria for depression, and the reported hazard ratio was nonsignificant in that study. A more recent study conducted by Mezuk et al. (

9) reported an association with new-onset diabetes mellitus in individuals with major depression that was detected in the community using the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule. However, most cases of depression in the general population, particularly in older age groups, may not be major (

10–

13).

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that clinically significant depression, not limited to major depressive disorder, increases the risk of diabetes mellitus in the general population. In addition, we examined the effect of the following characteristics of depression frequently observed in previous community studies: nonsevere depression, first-ever depression, persistent depression, and untreated depression.

Results

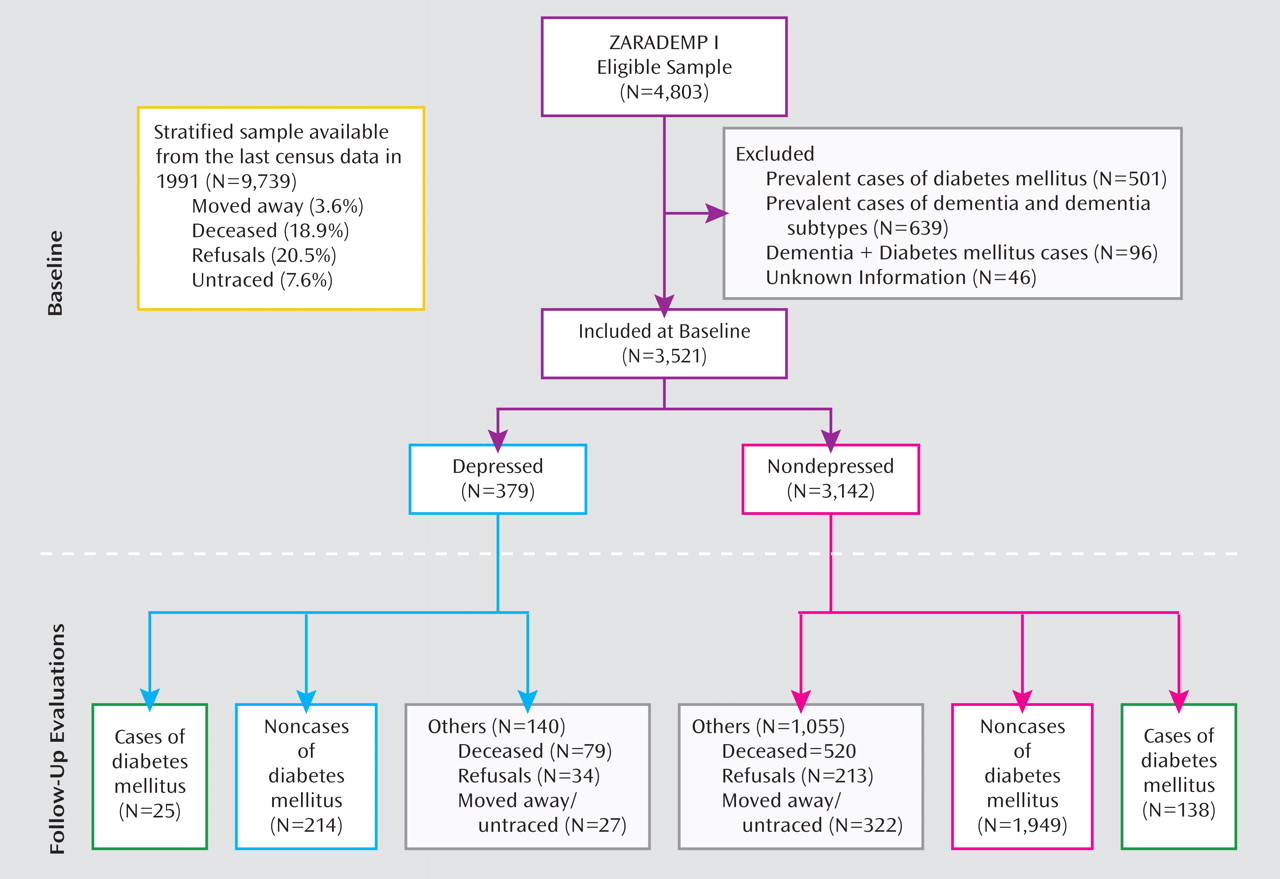

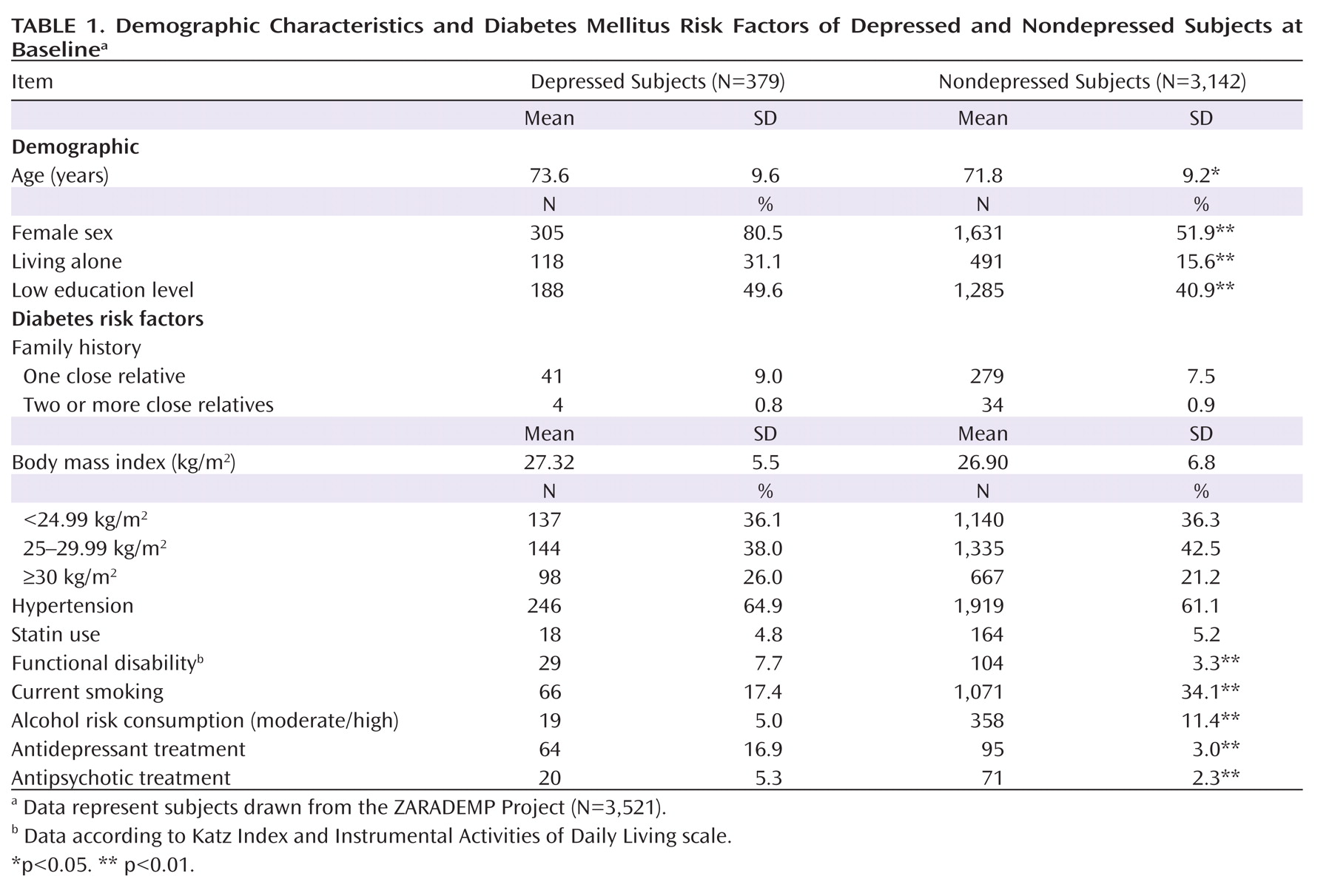

Of the total sample in the analysis for this study (N=3,521), 379 participants (10.8%) were diagnosed with depression. Baseline characteristics of depressed and nondepressed participants are shown in

Table 1. Compared with participants without depression, depressed subjects were 1.7 years older and were more likely to be female, to be less educated, to live alone, and to have a functional disability. No significant differences were observed between groups in mean body mass index, statin use, family history of diabetes, or hypertension. Depressed subjects were less likely to be smokers and/or moderate to high alcohol consumers. In contrast, they were more frequently taking antidepressant and/or antipsychotic medication.

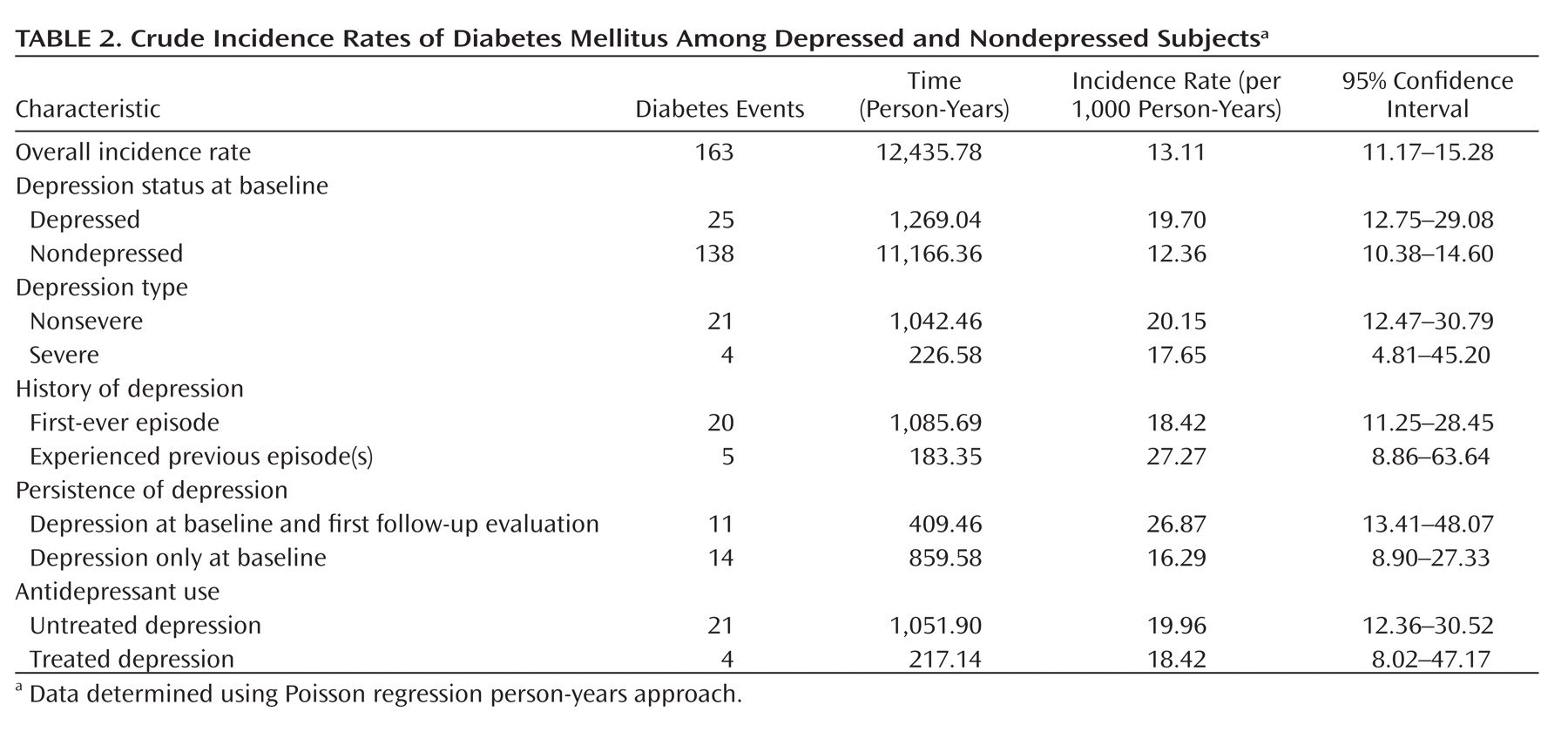

As seen in

Table 2, 163 incident cases of diabetes mellitus were found in the follow-up assessment waves (25 depressed subjects [6.6%] and 138 nondepressed subjects [4.4%]). The incidence rate was higher among depressed subjects (19.70 per 1,000 person-years) relative to nondepressed subjects (12.36 per 1,000 person-years).

In relation to characteristics of depression, most individuals who were depressed at baseline (N=315 [83.1%]) were considered to have nonsevere depression; 51 [13.5%] had a history of depression; and 64 [16.9%] were taking antidepressant medication. At the follow-up assessments, 109 individuals (28.8%) continued to be depressed (persistent depression). The incidence rate of diabetes mellitus was higher in individuals who had nonsevere depression, a history of depression, and untreated depression. It was also higher for those who had persistent depression, when compared with each depression counterpart (e.g., severe versus nonsevere, previous versus first-ever).

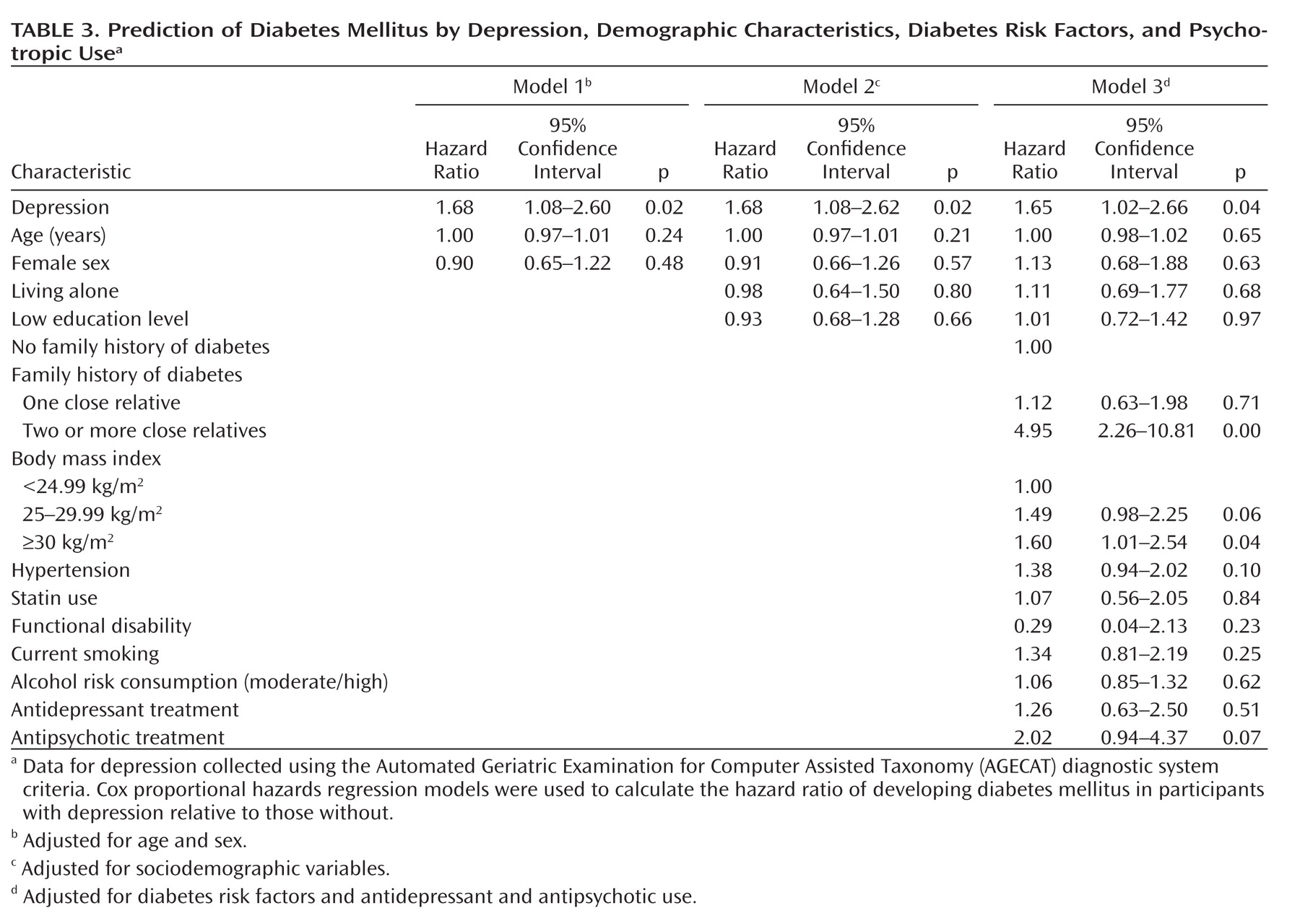

In the multivariate analysis (

Table 3), a significant association was observed between depression at baseline and incident diabetes mellitus, adjusted for age and sex (model 1). Other factors at baseline were also associated with incident diabetes mellitus, adjusted for age and sex. The risk estimates (hazard ratios) were 4.67 (95% CI=2.18–10.00) for family history of diabetes (two or more close relatives); 1.61 (95% CI=1.10–2.40) for body mass index 25–29.99 kg/m

2; 1.92 (95% CI=1.25–2.96) for body mass index ≥30 kg/m

2; and 1.57 (95% CI=1.08–2.27) for hypertension. The association between depression and incident diabetes mellitus persisted after adjustment for other sociodemographic variables (model 2) and after additional adjustment in model 3 for diabetes risk factors and antidepressant and antipsychotic use (hazard ratio=1.65; 95% CI=1.02–2.66). In this final model (model 3), incident diabetes mellitus was also associated with family history of diabetes (two or more close relatives) and with a body mass index ≥30 kg/m

2, but the association with both antidepressant and antipsychotic use was nonsignificant. By removing both antidepressant and antipsychotic use from the model, the increased risk of diabetes mellitus in depressed subjects persisted (hazard ratio=1.75 [95% CI=1.11–2.77, p=0.02]). In contrast, when depression was removed from model 3, the association of each psychotropic drug with diabetes mellitus increased but remained nonsignificant.

The population attributable risk percentage for diabetes mellitus, comparing depressed and nondepressed subjects and based on hazard ratios obtained after adjustment in model 3, was 6.87% (95% CI=1.04%–11.64%).

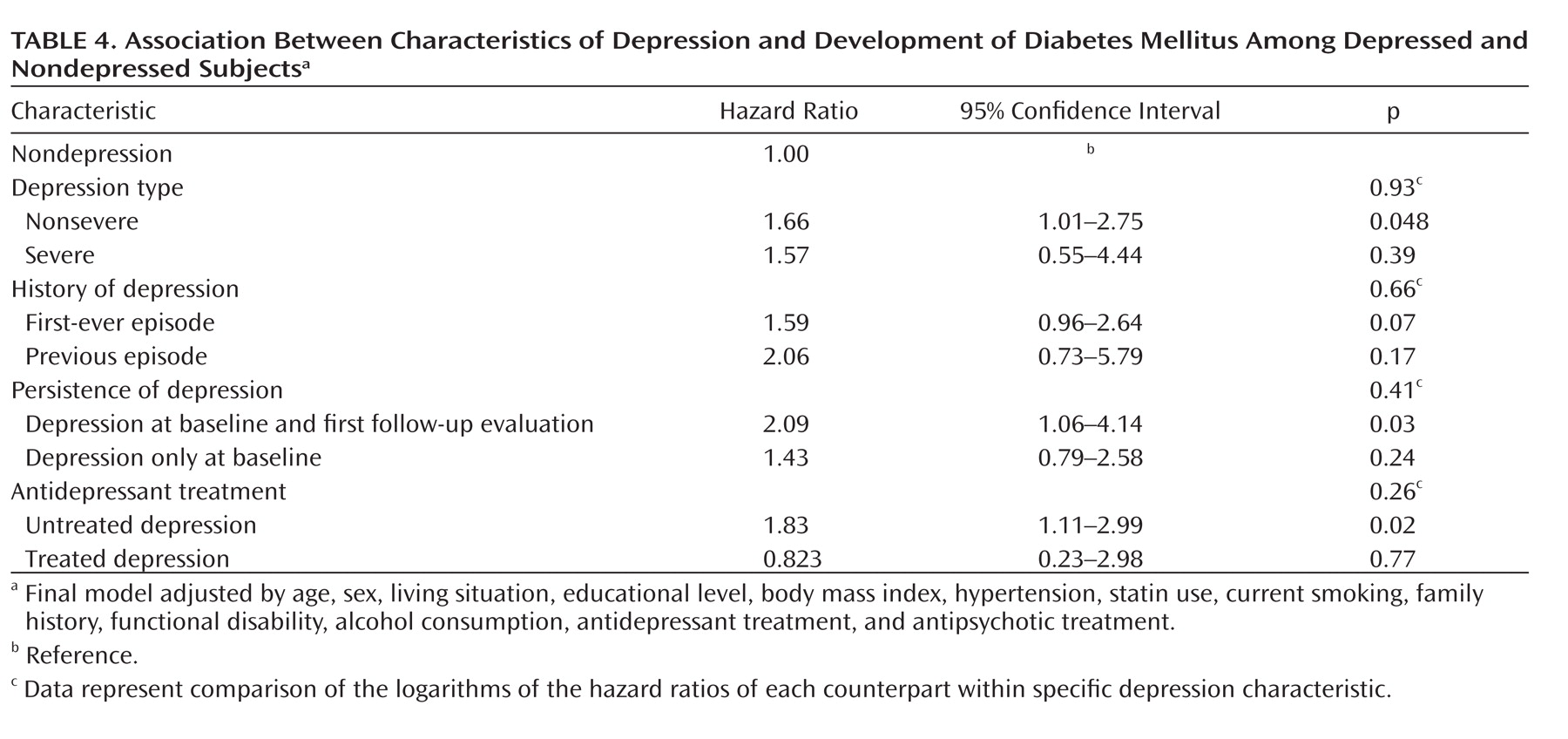

Table 4 shows hazard ratios for the development of diabetes mellitus in relation to depression characteristics. Compared with nondepressed individuals, participants considered to have nonsevere depression at baseline had a significantly increased risk of diabetes mellitus (hazard ratio=1.66 [95% CI=1.01–2.75, p=0.048]). Similarly, the risk was statistically significant for individuals with persistent depression (hazard ratio=2.09 [95% CI=1.06–4.14, p=0.03]) and for individuals with untreated depression (hazard ratio=1.83 [95% CI=1.11–2.99, p=0.02]). Furthermore, a nearly significant difference for developing diabetes mellitus was observed in individuals both with and without a history of depression. Directly comparing the hazard ratios associated with specific depression characteristics with each counterpart within depression (e.g., severe versus nonsevere, previous versus first-ever) did not result in any significant difference in hazard ratio.

Discussion

This 5-year longitudinal study of community dwelling adults aged ≥55 years supports the hypothesis that clinically significant depression increases the risk of diabetes mellitus. As expected, body mass index and, particularly, family history of diabetes (two or more close relatives) were associated with new-onset diabetes mellitus, and the association with other related factors, such as hypertension and antipsychotic use, was close to statistical significance. However, when we controlled for all of these potential confounders, the association of depression with diabetes mellitus remained statistically significant (hazard ratio=1.65 [95% CI=1.02–2.66, p=0.04]).

Two recent meta-analyses (

4,

7) previously reported an increased risk of developing diabetes in depressed individuals. However, most studies reviewed used self-reports or general physicians' diagnoses to document depression and therefore did not provide enough information on clinically significant depression. To our knowledge, only Epidemiologic Catchment Area studies have previously used a standardized psychiatric interview in this type of assessment. Eaton et al. (

8) did not find a significantly increased risk of diabetes mellitus, and Mezuk et al. (

9) reported an increased risk only in cases of major depressive disorder. In contrast, the association with new-onset diabetes mellitus in our study was not limited to major depressive disorder. Furthermore, the fact that we used standardized AGECAT diagnostic criteria (

15,

21) provided us with an advantage over many previous studies (

5). AGECAT "caseness" (confidence level ≥3) implies the "desirability of intervention" (

21,

26). A previous 4.5-year follow-up study conducted in Zaragoza, Spain (

13), supports the clinical implications in cases of depression detected using this system in the assessment of community elderly (42.0% of subjects died, and 22.7% remained depressed at the follow-up interview). The public health perspective in our study also seems relevant, since the estimated rate of diabetes mellitus attributable to depression was 6.87% (prevalence of depression: 10.8%). The population attributable risk is a function of the strength of the association and the prevalence of the risk factor. The estimated attributable risk was 9% in the Mezuk et al. meta-analysis (

4), with a reported prevalence of depression of 16%.

Our study suggests that the association with diabetes mellitus may vary according to some characteristics of depression. The increased risk of this endocrine disease in individuals with severe depression that was detected using AGECAT criteria was not statistically significant, but it is unclear whether the nonsignificant findings are the result of the relatively small number of severe cases or the magnitude of the association. However, we found a statistically significant increment in the risk of diabetes mellitus in individuals with nonsevere depression. This is remarkable, since most cases of depression with clinical repercussion in our study (83.1%), and similarly in other studies of community dwelling adults aged ≥55 years, were nonsevere (

10–

12,

21,

27). Cases of depression considered to be nonsevere using AGECAT criteria may be similar to those considered "minor" or "subthreshold" by some investigators (

28). In relation to DSM criteria, agreement with AGECAT criteria is considered "moderate" (

26). Data reported by Schaub et al. (

26) are fairly coincident with our previous data (

10,

12) and suggest that close to 50% of AGECAT "severe" cases of depression correspond to DSM-IV-TR criteria for "major" depression and approximately two-thirds of "nonsevere" cases correspond to DSM-IV-TR criteria for "minor" depression.

Contrary to van den Akker et al. (

29), we did not find an increased risk of new-onset diabetes in subjects with first-ever depression. However, van den Akker et al. limited their study to the population <50 years of age. Conversely, we found support for our conjectures about the increased risk for diabetes mellitus associated with both persistent and untreated depression. Carnethon et al. (

30) suggested the association with persistent depression, but their assessment was based on self-reports. We cannot claim that the hazard ratios associated with these specific characteristics explored are significantly higher when compared with each counterpart within depression. Nevertheless, the associations found are still noticeable because both persistent and untreated depression are commonly reported in population studies of the elderly (

12,

13).

In relation to treating depression in community studies of the elderly, there is conflicting evidence about the potential association of antidepressant use with new-onset diabetes mellitus (

31,

32). Andersohn et al. (

32) recently reported an increased risk in a large cohort of depressed patients in a clinical network. Their finding may lead to arguments about the possibility that antidepressant treatment and not depression itself increases the risk of diabetes mellitus. However, we did not find support for this argument, since we observed that depression increased the risk of new-onset diabetes after controlling for antidepressant use. Moreover, if we remove antidepressant treatment from the model, the increased risk of diabetes mellitus among the depressed patients persists, and if we remove depression from the model, the risk of diabetes mellitus does not increase significantly as the result of antidepressant treatment at baseline.

Some limitations to this study must be addressed. There was significant attrition from sampling to enrollment, which was higher than that of studies such as the Cache County Study (

33). However, the investigators in the Cache County Study considered their sample to be unusual and their response rate to be high. Moreover, the attrition rate in our sample was expected in the study design (

10,

14), and we previously argued that our investigation competes favorably with several two-stage epidemiological studies in this field (

14). It might also be argued that the exclusion of subjects with dementia at baseline from the two follow-up interviews might have affected the main findings related to incident diabetes mellitus. However, secondary analysis has shown no significant differences in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus between individuals with and without dementia. Since we have not found evidence that dementia modifies the risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus, we trust that this has not biased our study in any important way.

In view of previous reports (

34), we were surprised to find less frequent smoking among depressed subjects relative to nondepressed subjects and no differences in the frequency of body mass index categories. Cultural factors should be considered in relation to smoking, since women predominate in this sample and tobacco use is rare among women in this age group in Spain (

35), which is reflected in this study (tobacco use in women: 6.1%). The absence of differences between depressed and nondepressed subjects in relation to body mass index categories might be partially explained by differential loss between both groups for this particular variable. Since we used imputation techniques to address these losses, we also trust that our results have not been severely biased.

The main limitation in this and similar studies of self-reported diabetes relates to the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus in the absence of laboratory measures. We believe the information was acceptable in cases previously diagnosed by primary care physicians or specialists, but previous reports suggest that a considerable proportion of patients are not aware that they have diabetes mellitus (

36,

37). Undercounting cases of diabetes might be more important among depressed individuals, since they are less likely to see a doctor (

38). However, the resulting systematic misclassification would not modify the main conclusion derived from this study. False negative cases of diabetes among depressed subjects at baseline would be erroneously included in the denominator (person-years) for calculation of the incidence rate of diabetes. Moreover, undercounting diabetes among depressed subjects in the two follow-up waves would result in a decrement of the numerator (incident cases of diabetes) and the underestimation of the incidence rate of diabetes among this group. In this way, the rates for depressed subjects would come nearer to the rates for nondepressed subjects, and the risk ratio (hazard ratio) would be nonsignificant. However this is contrary to our findings.

In summary, previous reports have suggested that there is a robust association between depression and incidence of diabetes mellitus (

4). The results of this study, showing a 65% increased risk of diabetes mellitus associated with clinically significant depression, reinforce that conclusion. Furthermore, depression with characteristics frequently observed in the community, namely nonsevere, persistent, and untreated depression, is associated with an increment of risk of diabetes mellitus. In view of the epidemic nature of both diabetes and depression, we believe our results have important public health as well as clinical implications. However, whether interventions in depression lower the increased risk of diabetes has yet to be examined.