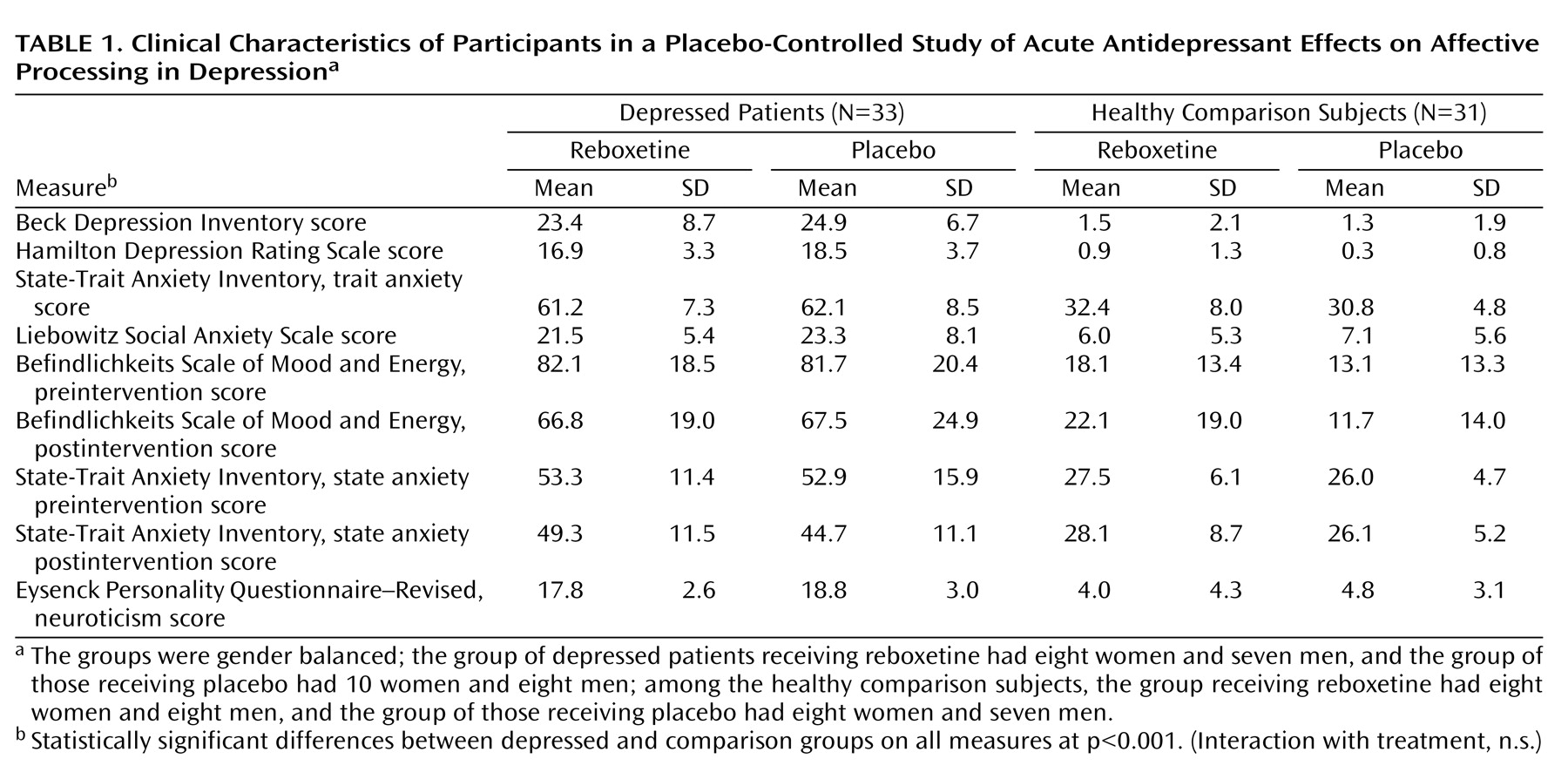

Cognitive psychological models of depression emphasize the importance of negative biases in information processing in the etiology and maintenance of depressive disorders

(1) . Experimental evidence suggests that depressed patients are more likely to remember negative than positive emotional information in self-relevant tasks

(2,

3) and to interpret key social signals, such as facial expressions of emotion, as either more negative or less positive than do matched healthy volunteers

(4 –

6) . Such effects have been linked to increased risk of relapse

(4) and are thought to fuel negative thinking and low mood in depression

(1) .

We recently hypothesized

(7) that antidepressant drug treatments may produce their ultimate clinical effects by normalizing these negative biases in information processing. Indeed, healthy volunteers show early effects of antidepressants on emotional processing even in the absence of subjective changes in mood. For example, a single dose of the norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor reboxetine was found to increase the recognition of happy facial expressions, speed responses to positive self-referent information, and facilitate memory for these positive personality characteristics

(8) . Similar effects on the recognition of happy facial expressions have been seen with acute administration of both the serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram

(9,

10) and the serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor duloxetine

(11), which suggests that such changes in emotional processing may be a common effect of pharmacological treatments effective in the management of depression. Early effects of antidepressants on emotional processing may contribute to later changes in mood and symptoms as the patient learns to respond to this new and more positive intra- and interpersonal environment.

The early effects of antidepressant treatment on emotional processing have been characterized in healthy volunteer samples. However, it is not known whether these early changes in emotional processing also occur during the treatment of acutely depressed patients, and if so, whether they are of a magnitude similar to those seen in healthy volunteers. In this study, we examined the effect of a single dose of reboxetine compared to placebo on emotional processing in a sample of unmedicated patients with major depression and matched healthy comparison subjects. The same three measures of emotional processing found to be affected by antidepressant administration in healthy volunteers were used here

(8,

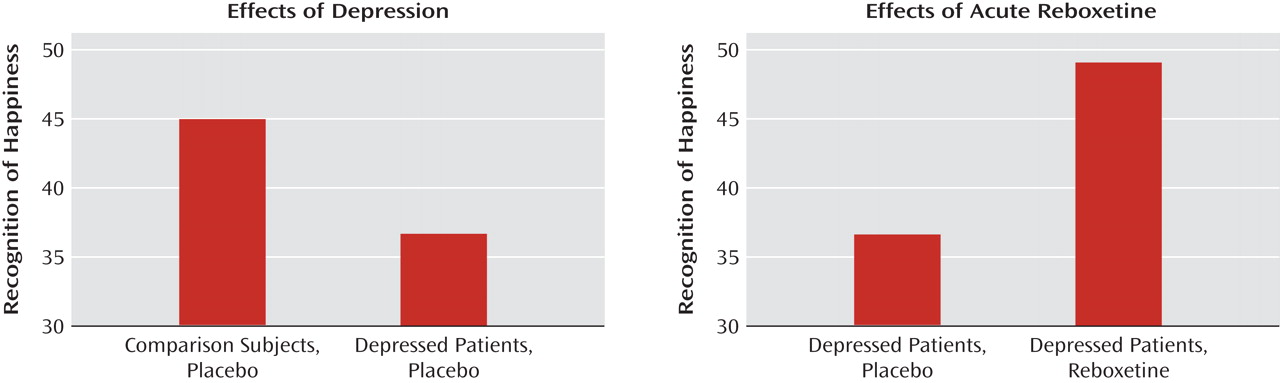

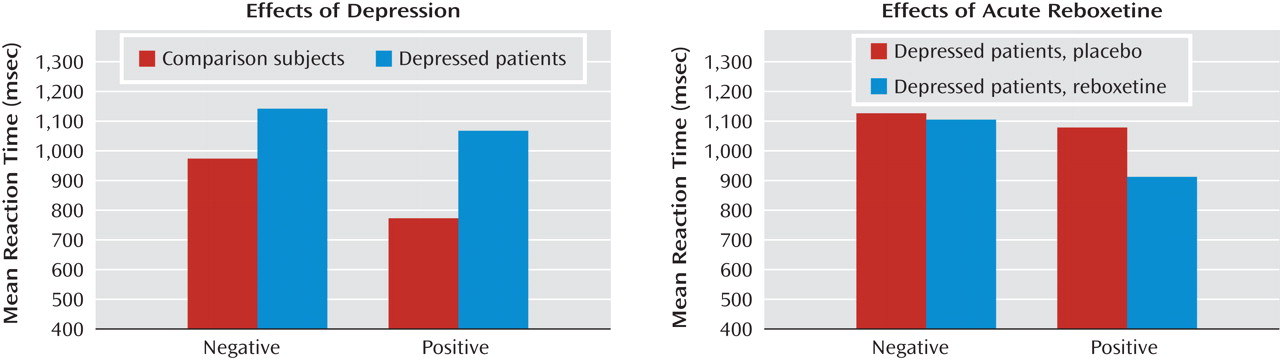

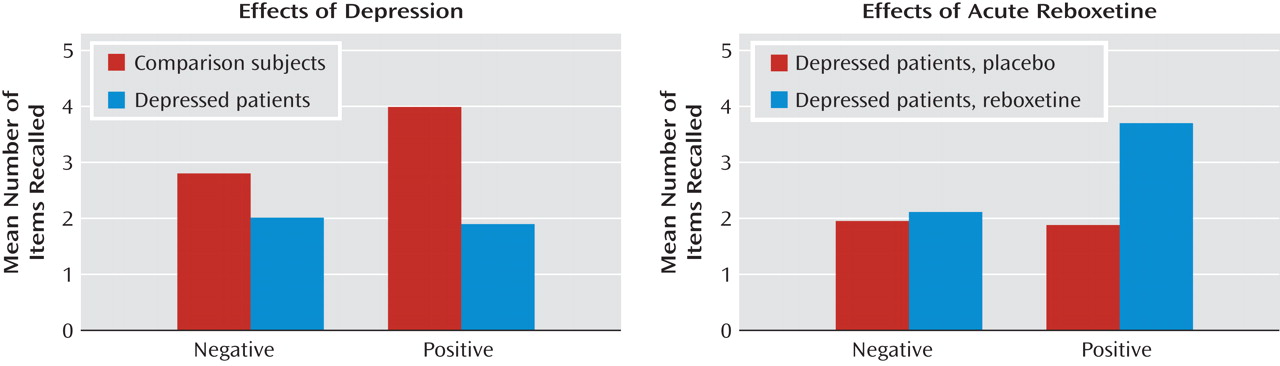

12) . We hypothesized that acutely depressed patients would show negative biases on these measures compared to healthy volunteers when receiving placebo. This would be manifested as lower recognition of happy facial expressions, lower speed in identifying positive versus negative self-descriptors, and lower recall for positive personality descriptors. Administration of reboxetine was predicted to reverse these effects and lead to increased positive emotional processing on these same measures in the absence of changes in mood.

Discussion

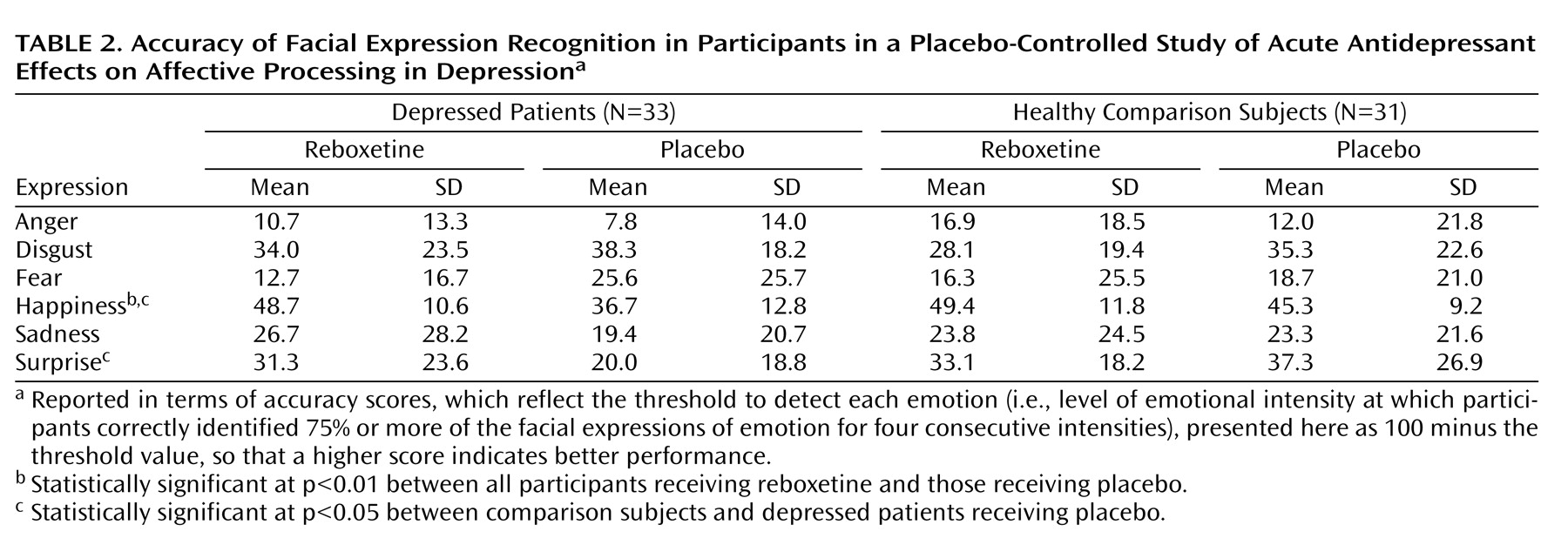

Our findings indicate that acute administration of an antidepressant can modify emotional processing in acutely depressed patients. Under placebo conditions, the depressed patients showed reduced recognition of positive facial expressions, decreased speed to respond to positive self-relevant personality adjectives, and reduced memory for this positive information compared to matched healthy volunteers. However, a single dose of reboxetine reversed these effects in the absence of changes in subjective ratings of mood or anxiety. The magnitude of the effects of reboxetine on emotional processing was either similar or larger in the depressed patients relative to the healthy volunteers. These results therefore validate our previous findings from healthy volunteer groups

(8 –

12) and suggest that the same effects are seen in depression early on in treatment with antidepressant drugs.

The reduced positive affective processing seen here in unmedicated depressed patients is consistent with cognitive theories that emphasize the role of such biases in underlying etiology

(1,

23) . Similar to the results we present here, previous studies have also reported reduced recognition of positive facial expressions and/or increased recognition of aversive facial expressions in depressed patients, as well as negative biases in self-referent emotional memory (for a review, see reference

24 ). This replication indicates that our emotional processing tasks are sensitive to the negative emotional biases that are characteristic of the depressed state. It is remarkable that the effects of reboxetine were almost exactly the converse of the effects of depression, suggesting that antidepressants could work by targeting the negative and often implicit biases in emotional processing that are believed to characterize and maintain the disorder.

The therapeutic effect of antidepressant treatment requires time and repeated administration to become clinically apparent. This is often taken to prove that the key neurobiological change may also be delayed in some way. In fact, this interpretation of clinical trial data and clinical experience may be less soundly based than is often assumed. The rate of improvement in depressive symptoms over the first week of treatment with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) is at least as great as in subsequent phases of treatment

(25) . This could imply that the causal change takes place immediately and sets in train a process with a fixed time course. It is therefore striking that effects of antidepressant treatment on emotional processing in depressed patients can be seen even with a single administration of half the daily dose recommended for treatment. We have hypothesized that the critical time lag in antidepressant drug action does not result solely from a delay in relevant neuropharmacological actions, such as desensitization of autoreceptors or the requirement for neurogenesis

(7) . Instead, we suggest that there is an inherent delay between the effects of antidepressants on emotional processing and the subsequent effects on mood. According to this view, effects of antidepressants on emotional bias are seen rapidly, but the translation of these changes into improved subjective mood takes time as the patient learns to respond to this new, more positive social and emotional perspective of the world

(7) . An increased tendency to interpret social signals as positive may not immediately lead to improved mood but could reinforce social participation and social functioning, which over repeated experience improve mood and the other symptoms of depression. This does not exclude a critical role for delayed neuropharmacological effects, but the therapeutic delay before clinical benefit does not prove their existence, as is often assumed.

Negative biases in information processing in depression and anxiety are the explicit target for psychological treatments such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

(1) . The actions of antidepressant treatment are not usually explored in a psychological framework, and reductions of biases toward aversive information following antidepressant treatment are often attributed to mood improvement. However, our results show that antidepressants change emotional processing and memory in depression very early on in treatment and in the absence of a measurable change in subjective mood. These results therefore suggest that cognitive theories of depression may also be relevant to antidepressant drug action, with different treatments having the potential to affect similar underlying processes. Indeed, researchers have reported overlapping as well as distinct effects of CBT and antidepressant drug treatment on cerebral blood flow in neuroimaging studies

(26,

27), which supports the idea that there may be some commonalities in their neural mechanisms of action. The challenge now remains to explore such effects early on in treatment to help us understand to what extent these approaches are similar prior to the induction of clinical changes in mood state.

This study has a number of limitations. Although the depressed patients in our sample all met criteria for a current episode of DSM-IV depression, symptom severity fell within the mild to moderate range largely because of the need to recruit an unmedicated sample. The negative biases seen in these patients validates this approach, but further studies are required to replicate these effects in a larger and more severely affected group, also allowing for correlation analyses to be performed between clinical ratings and emotional processing performance. It is also unknown whether similar effects are seen early on in the treatment of depressed patients with other antidepressant drugs, including the more commonly used SSRIs. A recent meta-analysis suggests that reboxetine may be less effective in the treatment of depression than other second-generation antidepressants

(28), which may seem to contrast with the robust effects seen here in the experimental medicine model, although there is also evidence that such clinical observations with reboxetine are partly a consequence of poor tolerability and high dropout rates rather than reduced efficacy

(29) . Further study is nonetheless required to assess whether this experimental medicine approach can discriminate between agents with different levels of efficacy early on in treatment and whether those agents that perform well in the clinic are also those with the strongest early effects on emotional processing measures.

The significant effects on emotional processing that we have seen in depressed patients after a single dose of reboxetine raise the possibility that models of emotional processing may be useful in drug development and screening. If acute effects in emotional processing measures are seen reliably with effective antidepressants in depressed patients, then performance in these models may be a useful way of screening novel candidate antidepressant agents before full-scale clinical trials are initiated

(30) . It is also possible that individual effects on these measures could be used to predict eventual response in depressed patients starting treatment. Consistent with this, increased recognition of happy facial expressions after 1 week of treatment with citalopram in depressed patients predicted eventual therapeutic response after 6 weeks of continued treatment

(31) . Such findings highlight a potentially critical role for early changes in emotional bias in therapeutic efficacy.