Seasonal affective disorder was first described in 1984

(1) and was incorporated into DSM-III-R as “seasonal pattern,” a modifier to be applied to recurrent forms of mood disorders, rather than as an independent entity. It remains a modifier in DSM-IV.

The classification rules of DSM-III allowed only one axis I diagnosis, to which all other diagnoses were subordinated. For example, one could not have both seasonal affective disorder and bipolar disorder as two separate diagnoses. The adjectival modifier was the deus ex machina that enabled both conditions to be recognized. These rules were sensibly changed in DSM-III-R and DSM-IV, when comorbid diagnoses were permitted. In light of these changes, the status of seasonal affective disorder should be reconsidered.

Many convergent lines of research justify its classification as an independent disorder. The clinical picture is distinct: patients with seasonal affective disorder, predominantly women, become regularly depressed in autumn and winter and experience remission in spring and summer. They experience characteristic atypical vegetative symptoms during their depressive episodes and have a history of reactivity to environmental light (the more the better). Seasonal affective disorder increases in prevalence with increasing distance from the equator

(2) and has been described in the southern, as well as the northern, hemisphere

(3) .

Predictive validity is supported by prospective studies in which patients recruited during the summer while they are well become depressed in fall and winter

(1,

4) . When depressed, patients respond favorably to treatment with bright environmental light

(1,

5) . Researchers have worked to delimit patients with seasonal affective disorder from those with other forms of major depressive disorder. For example, Pendse et al. found that, contrary to their hypothesis, outpatients with seasonal affective disorder had more severe psychopathology than inpatients with nonseasonal major depression who had attempted suicide

(6) . Likewise, Sullivan and Payne found the condition to be more clinically severe and more prevalent than nonseasonal major depressive episodes in a college setting

(7) .

Of numerous biological studies in patients with seasonal affective disorder, several identify impaired ocular processing of light

(8,

9) . Patients also evidence seasonal changes in melatonin secretion not seen in healthy comparison subjects

(10) . There is also ample evidence of deficient serotonergic transmission, which may be reversed by exposure to bright light

(11,

12) .

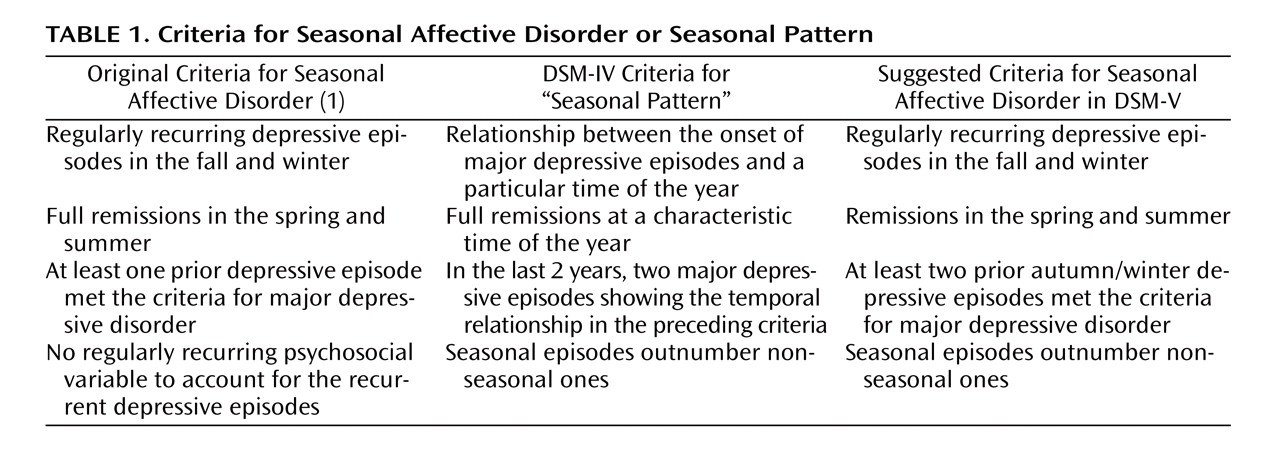

Suggested criteria for a DSM-V diagnosis of seasonal affective disorder are shown in

Table 1 . Aside from patients with clear diagnostic criteria for seasonal affective disorder, many patients, both those with mood disorders and those with other conditions, show seasonal variations in symptoms. Some worsen in summer; others in winter. Thus, it would be useful to provide the modifiers “with winter worsening” and “with summer worsening” for patients with any axis I condition (other than seasonal affective disorder) that worsens in the corresponding season. Although a summer form of seasonal affective disorder has been described

(3), it has not been sufficiently well studied to warrant a diagnostic category of its own at this time.

In conclusion, clinical, predictive, and biological data present a strong case for the construct validity of seasonal affective disorder. Substantial evidence suggests that patients with seasonal affective disorder have deficits in processing visual light, develop symptoms in the absence of adequate light, and respond favorably to enhanced environmental lighting. It would seem timely for DSM-V to recognize the scientific basis for the validity of this disorder as an entity and provide it with a category of its own. Now that psychiatric diagnoses are no longer hierarchical, a patient could be diagnosed with both seasonal affective disorder and bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder.