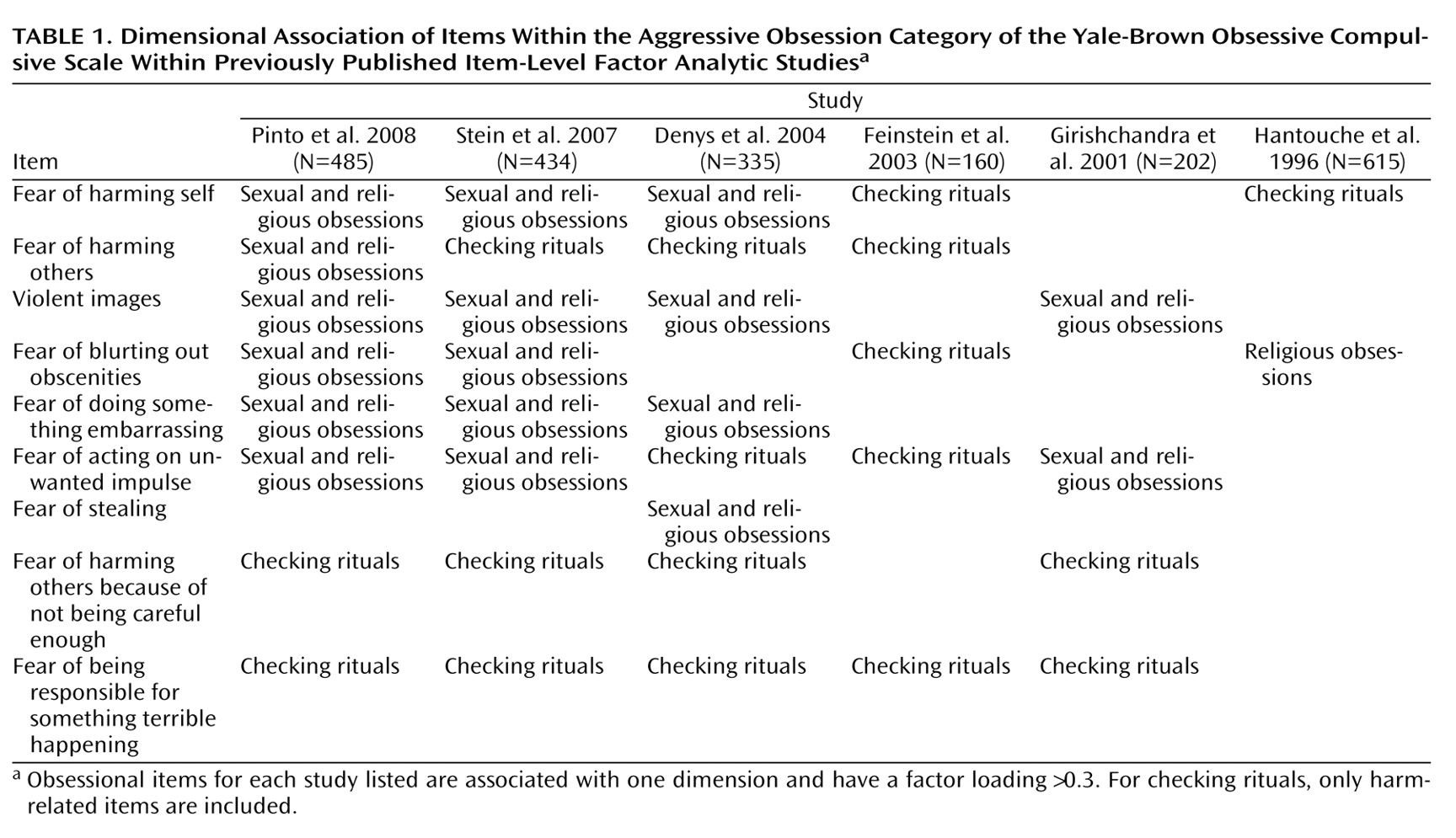

To the Editor: We thank Dr. Pinto et al. for their interest in our recent article. Their item-level factor analytic studies have provided important evidence supporting the division of the aggressive obsession symptom category into two item-level groupings. As noted in their letter, a first-proposed grouping includes items from the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale–Symptom Checklist related to over-responsibility for harm (e.g., “fear I will harm others because I am not careful enough”; “fear I will be responsible for something else terrible happening”). The other proposed grouping of aggressive obsession items involves aggressive images and impulses (e.g., “violent or horrific images”; “fear of acting on unwanted impulses”; “fear of blurting out obscenities and insults”; “fear of doing something else embarrassing”; “fear I will harm others”). However, while these item-level analyses support such a division, others do not. The optimal classification of individual aggressive obsessions remains unresolved and must await further item-level factor analyses that report on larger numbers of subjects.

Dr. Pinto et al. cite two recent item-level factor analytic studies in which the aggressive obsession category split into these two separate item groupings, with the aggressive imaging items being associated with sexual and religious obsessions while the over-responsibility for harm items were associated with checking items

(1,

2) . Other support for this proposed division comes from a large confirmatory factor analysis that replicated the four-symptom dimension structure reported in our meta-analysis for category-level but not item-level data

(3) . The inconsistent associations between aggressive, sexual, religious, somatic, and checking symptom categories within category-level factor analytic studies may constitute further circumstantial evidence supporting this separation. This inconsistency could be explained by the combination of 1) different prevalences of item-level symptoms between study cohorts within categories and 2) differing relationships of item-level symptoms within a category with other symptom categories.

However, several other item-level factor analytic studies have not supported this separation of items within the aggressive obsession category

(4 –

7) .

Table 1 illustrates the association of item-level aggressive obsessions from the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale–Symptom Checklist with sexual obsessions, religious obsessions, and harm-related checking items (e.g., “checking that I did not harm others”; “checking that I did not harm self”; “checking that nothing else terrible will happen”; and “checking locks, stoves, appliances, etc.”) in published exploratory item-level factor analytic studies.

All studies agree that items in the group of aggressive obsessions on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale–Symptom Checklist associate with sexual, religions, and/or checking symptoms and not with other symptom clusters. However, some item-level factor analytic studies support the association of the aggression items with only checking behaviors

(5) or place them in their own dimension

(6) . Continued item-level factor analytic studies similar to those already published may not efficiently resolve this ambiguity—21 individual-factor analytic studies did not settle this debate at a category level prior to meta-analysis and confirmatory factor-analysis

(8) . A better approach may be for researchers to pool their data for a larger more definitive item-level factor analysis of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale–Symptom Checklist or to conduct confirmatory factor analyses to existing factor structures.

There are several other symptom types that have not been well-defined by categorical factor-analytic approaches. These include somatic obsessions (e.g., “concern with illness or disease”; “concern with appearance”), miscellaneous obsessions (e.g., “need to know or remember”; “fear of saying certain things”; “fear of not saying just the right thing”; “fear of losing things”; “intrusive nonviolent images”), and rituals (e.g., “excessive list making”; “need to tell, ask, or confess”; “measures besides checking to prevent harm to self, others, or terrible consequences”; “need to touch, tap, or rub”). A large pooled item-level factor-analytic study or meta-analysis of published studies will help place these symptoms in appropriate dimensions.

The appropriate placement of checking symptoms within OCD symptom dimensions remains elusive. Although the individual items in the checking category of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale–Symptom Checklist explore well the symptoms of checking associated with harm (e.g., “checking that did not harm others”; “checking that did not harm self,” “checking that nothing else terrible will happen”; and “checking locks, stoves, appliance, etc.”) and checking associated with somatic symptoms, individual items of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale–Symptom Checklist neglect checking symptoms associated with symmetry, contamination, and sexual and religious obsessions. Checking associated with symmetry obsessions appears particularly prevalent in children. Item-level analysis of scales, such as the Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, that have further expanded checking symptom items to those associated with other symptom categories will be further helpful in describing the symptoms of OCD

(9) .

Clearly, significant areas of uncertainty regarding the dimensional structure of OCD remain, as highlighted by Dr. Pinto et al. However, there are also significant areas of consensus. The validity of the hoarding, symmetry, and cleaning dimensions is generally acknowledged. Furthermore, there is compelling evidence that sexual and religious symptoms belong in the same symptom dimension, along with many (but probably not all) aggression and, possibly, checking items. There also appears to be increasing consensus as to the potential power of a dimensional symptom structure in explaining some of the phenotypic heterogeneity of OCD in genetic and imaging studies and potentially in treatment response.

We urge authors using category-level data to conduct confirmatory factor analyses with the 4-factor structure put forth in our meta-analysis and several confirmatory factor analyses rather than conducting new exploratory factor analyses

(3,

8) . For item-level data, we recommend confirmatory factor analysis toward the four-factor category dimension solution or a five-factor item-level solution, with additional exploratory factor analysis only when the fit in this initial analysis is poor. The practice of performing novel exploratory factor analyses and then linking results of genetic, imaging, or treatment studies with these analyses has made the literature difficult to interpret. Different factor analyses tend to appear rather dissimilar when in reality the underlying structure might be very similar. This phenomenon occurs because the similarities between studies are often masked through differences in factor number and factor rotation. Given this tendency, we should work toward areas of consensus rather than differences in order to utilize dimensional factors to help interpret and optimize emerging research in OCD.