Implementation of evidence-based care has been suboptimal for chronic illnesses

(1), especially serious mental illnesses

(2) . Improving concordance with evidence-based clinical practice guidelines has been a cornerstone of efforts to enhance quality of care and improve outcomes

(1) . However, guidelines for the treatment of mental illnesses are underdeveloped

(3) and not routinely well implemented in usual care

(4) .

Bipolar disorder is a chronic serious mental illness associated with multiple medical and psychiatric comorbidities, substantial functional deficits, and high suicide rates (see reference

5 for a review). It is the most expensive mental health condition for U.S. health plans

(6) . Evidence-based treatments are available, particularly for antimanic medication and maintenance treatment, and have been codified in multiple clinical practice guidelines

(7) .

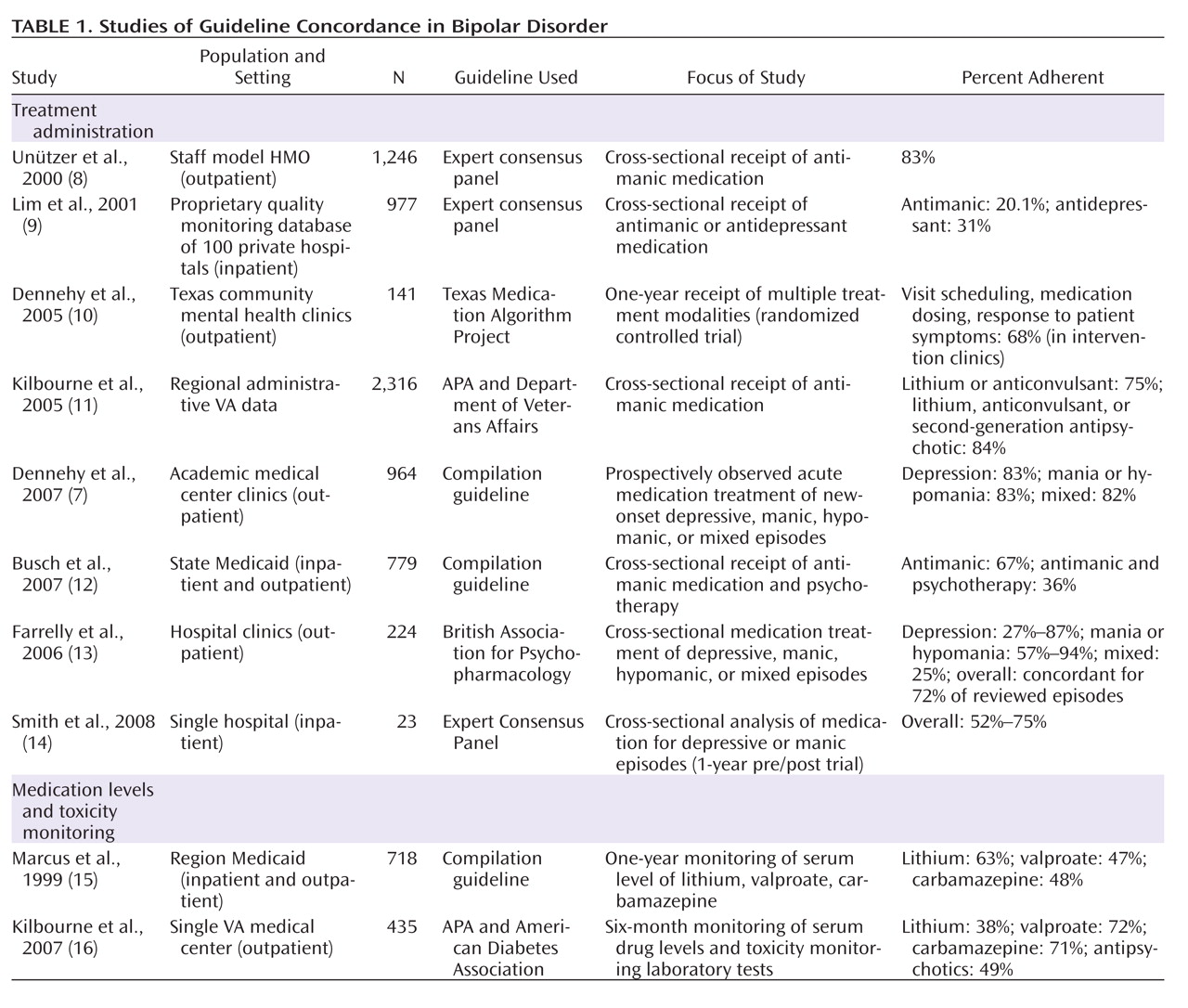

Guideline concordance rates for bipolar disorder vary widely (

Table 1 ), and only one randomized controlled trial assessing guideline concordance has been published. That study, the Texas Medication Algorithm Project

(17), used a guideline-focused disease management program in a state mental health system. The trial demonstrated improved clinical outcomes in individuals treated in intervention clinics relative to those treated in comparison clinics that received no guidelines or disease management training or resources. In a secondary analysis

(10), investigators demonstrated enhanced guideline concordance compared to baseline across three guideline domains in 141 patients followed for 1 year in intervention clinics, although no data were available for usual-care clinics. Better guideline adherence in this analysis was significantly associated with better outcomes.

Other related multicomponent interventions also show promise in enhancing guideline-concordant care for mental disorders. For instance, based on chronic medical illness care models

(18,

19), collaborative chronic care models have been shown to improve concordance with practice guidelines for depression treated in primary care (see references

20 –

22 as examples).

Collaborative care models for bipolar disorder have been tested and compared with usual care in randomized controlled effectiveness design

(23,

24) trials. These trials have demonstrated improved clinical outcomes

(25 –

27), improved social role functioning

(26), and improved mental

(26) or physical

(28) quality of life. In two multisite, multiyear randomized controlled trials, collaborative care models produced significant reductions in manic symptoms

(26,

27) . We thus considered that one potential mechanism for the long-term effects of collaborative care models for bipolar disorder is enhanced delivery of evidence-based antimanic treatment over the long term. Using data from one of these trials

(25,

26), we investigated the hypothesis that treatment with the collaborative care model improved multiyear concordance with guideline recommendations for antimanic treatment.

Method

Data for this study derive from Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Cooperative Study Program 430 (CSP 430), “Reducing the Efficacy-Effectiveness Gap for Bipolar Disorder,” conducted from 1997 to 2004. Methodological details are available elsewhere

(24,

25,

29) . Briefly, across 11 VA medical centers, 306 veterans hospitalized for bipolar disorder were randomly assigned at hospital discharge to receive 3 years of treatment in the collaborative care model or continued usual care. To be included, patients had to be age 18 or older, have a diagnosis of bipolar I or II disorder, and have had at least three prior psychiatric hospitalizations over the previous 5 years. Exclusion criteria, consistent with the effectiveness design of the trial

(23,

24), were minimal: dementia, a terminal illness with a life expectancy <3 years, and inability to provide informed consent. No other medical or psychiatric comorbidities were excluded; veterans who were intoxicated or withdrawing from substances were approached for recruitment only after resolution of acute withdrawal symptoms. Study procedures were approved by the relevant human subjects review boards. As noted above, compared to usual care over 3 years, collaborative care resulted in fewer weeks of mania and weeks in any affective episode and improved social role functioning and mental quality of life, with no net increase in total direct treatment costs

(26) .

Participants

As reported elsewhere

(25,

30,

31), the sample reflected the population of veterans seeking mental health care in the VA health care system; the mean age was 46.6 years (SD=10.1); 9% were female, and 23% were from minority groups. The sample was psychosocially complex, with 70% other than married or widowed and 13% homeless. The sample was also severely ill. Eighty-seven percent had bipolar I disorder, 34% were psychotic at intake hospitalization, 65% had a history of suicide attempt, and the sample had had a mean of 5.3 hospitalizations (SD=5.5) over the previous 5 years. Current comorbidity was the rule, with substance use disorders in 34% (lifetime diagnosis, 72%), anxiety disorders in 38% (lifetime diagnosis, 43%), any current psychiatric comorbidity in 79%, and active medical comorbidity requiring treatment in 81%.

Intervention

The collaborative care model consisted of three manual-based components

(24,

25,

29), which correspond to the core elements of chronic care models for medical illnesses

(18,

19) : patient self-management skills enhancement via structured group psychoeducation, provider support through evidence-based VA clinical practice guidelines in simplified format, and enhanced access to and continuity of treatment through a nurse care manager working in conjunction with a designated psychiatrist. Treatment of bipolar disorder was transferred to collaborative care clinics staffed by a part-time psychiatrist and a half-time nurse, with a nurse-to-patient ratio of approximately 1:50. All other mental and medical health care was provided as clinically indicated.

Randomization of patient assignment was conducted within medical centers, and usual care within medical centers was not constrained. In order not to disrupt usual care and to maintain a light research “footprint,” no specific process measures were taken during the study to characterize usual care, although we know from study-end analyses that there were no significant differences in either outpatient mental health treatment costs or inpatient all-cause treatment costs

(26) . VA guidelines for bipolar disorder were released in 1997

(32), and there was no concerted effort (and there still has not been) to implement them via clinical reminders, patient registries, or performance measures linked to these measures. Thus, usual care reflects the situation that is encountered in many clinical settings in a variety of health care systems: guidelines were available and were endorsed by the organization, but no specific effort was made at the clinic or provider level to monitor or enhance their implementation.

Medication Recording

At baseline and for six prospectively assessed 6-month intervals, medication utilization data were gathered by research assistants who reviewed pharmacy records, laboratory results, and progress notes and interviewed patients to ascertain medication utilization based on the best available information, including patient self-reports of adherence. For the 6 months preceding randomization and 3 years of prospective follow-up, these data were recorded according to a standardized instrument

(29), an updated version of the one developed for the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Study on the Psychobiology of Depression

(33) . Data collected included dosages and serum levels of lithium, carbamazepine, and valproate; dosages of first- and second-generation antipsychotics; dosages of antidepressants; and adjuvant bipolar medications. For recording purposes, first-generation antipsychotics were converted to chlorpromazine equivalents, second-generation antipsychotics to risperidone equivalents, and antidepressants to imipramine equivalents

(34) . Research assistants were trained to criterion and found to have high reliability in the study measures

(24,

25,

29), and pilot work showed that the medication assessment procedures were sensitive to change

(29) .

Antimanic Treatment Guideline Concordance

All clinical practice guidelines include multiple choice points for multiple conditions. We focused our analyses on antimanic medication treatment for several reasons. First, it meets the criteria of meaningfulness, feasibility, and actionability proposed for choosing quality measures

(3) . Second, the two long-term collaborative care trials that have been conducted

(23,

24) indicated that reduction in manic symptoms was probably an important component of beneficial collaborative care effects. Third, major practice guidelines for bipolar disorder recommend antimanic treatment on an ongoing basis (see reference

7 for a review); thus, at any point in time, independent of mood state, one would expect guideline-concordant care for bipolar disorder to include antimanic treatment. Episode-specific treatments (e.g., administration of antidepressants in a depressive episode, cessation of antidepressants during a manic episode) were not considered in these analyses.

Collaborative care providers were trained in the use of a simplified, one-page summary guideline based on the 1997 VA Clinical Practice Guidelines for Bipolar Disorder

(32) and received ongoing technical assistance via monthly conference calls; usual-care providers received the printed guidelines alone. These guidelines specify the primary use of lithium, and secondarily valproate or carbamazepine, for antimanic and maintenance treatment; thus, according to these older guidelines, at least one of these medications should be administered at all times in the course of bipolar disorder. While drug classes were specified (e.g., antimanic agent), the choice of individual agent (e.g., lithium versus valproate) was left to shared decision making between provider and patient

(29) . Because the guidelines were compiled before the development or widespread use of second-generation antipsychotics for antimanic or maintenance treatment, they were updated at midstudy to include any second-generation antipsychotic, with the recommendation of treatment with at least 2.0 mg/day of risperidone equivalents.

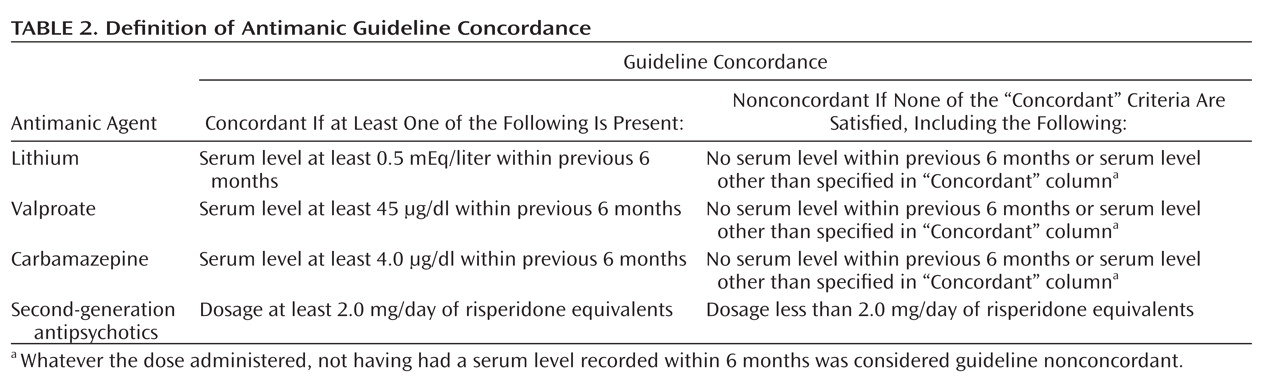

The definition of guideline concordance is summarized in

Table 2 . For example, if a patient’s treatment during an epoch consisted of 600 mg/day of lithium and the patient had a serum level of 1.0 mEq/liter, that epoch was considered concordant. If treatment during an epoch consisted of 2400 mg/day of lithium but no serum level was obtained within the previous 6 months, that epoch was considered nonconcordant. With combination treatment, an epoch was considered concordant if at least one treatment was concordant (e.g., 5 mg/day of risperidone equivalents plus 300 mg/day of lithium and no serum level); however, two nonconcordant treatments were not considered guideline-concordant (e.g., lithium with a serum level of 0.2 mEq/liter plus valproate with a serum level of 25 μg/dl). Thus, our primary hypothesis was that collaborative care would be associated with higher rates of receiving any of the more recent antimanic treatments as specified in

Table 2 during each 6-month epoch.

Since first-generation antipsychotics were in wider use at the outset of the study, we also conducted a sensitivity analysis that defined concordant treatment to include recommendations in

Table 2 or 100 mg/day of chlorpromazine equivalents

(33) . Results did not differ substantively from analyses using the

Table 2 criteria alone, so only analyses based on the

Table 2 criteria are presented here; that is, lithium, carbamazepine, valproate, and second-generation antipsychotics were considered guideline-concordant antimanic medications, but first-generation antipsychotics were not considered.

Statistical Analyses

Guideline concordance (yes/no) was determined at baseline for the previous 6 months and for each of six prospectively assessed 6-month epochs. These six prospective measurements served as primary outcome variables in a repeated-measures analysis using generalized estimating equations with an autoregressive correlation structure used to model the correlations between concordances at successive time points. The repeated-measures model was run using treatment group (collaborative care versus usual care), epoch (time), baseline concordance, bipolar type (I versus II), and age as main effects, with a treatment-by-time interaction term. SAS, version 9.2, was used for the analyses.

Discussion

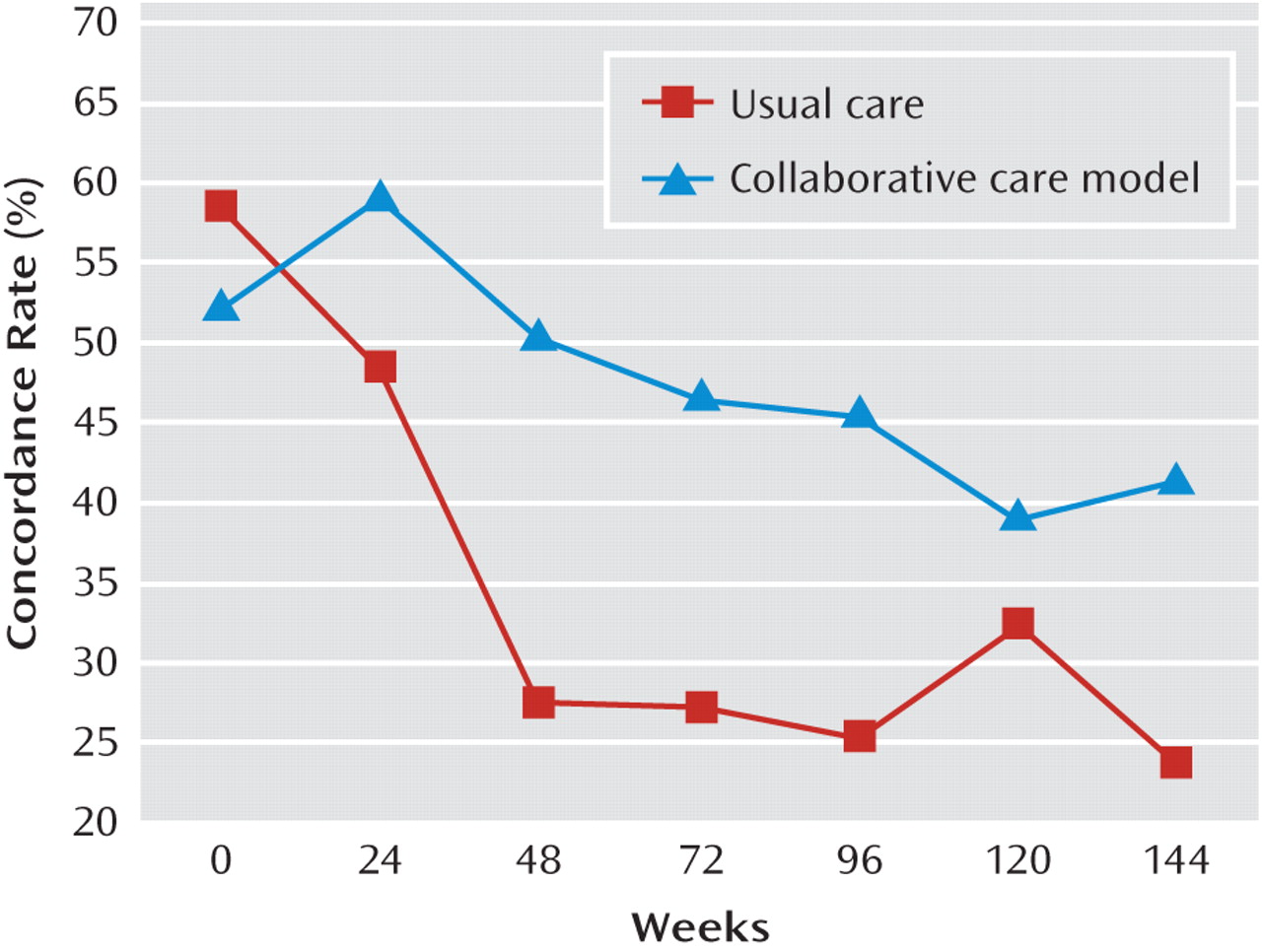

This study provides the first prospectively collected data of more than 1 year’s duration on clinical practice guideline concordance in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Additionally, it provides the first prospective bipolar clinical trials data comparing guideline concordance in an intervention group and a comparison group. Treatment in the multicomponent collaborative care model significantly improved and sustained long-term guideline concordance rates compared to usual care. These benefits were demonstrated despite enrolling a severely ill population with high rates of medical comorbidity, psychiatric comorbidity, suicidality, and psychosis. The lack of effect of age and bipolar type indicates that these benefits are relatively broad-based.

Compared with the 1-year Texas Medication Algorithm Project trial, which achieved 68% concordance with the intervention

(10), the first-year guideline concordance rates with collaborative care were somewhat lower (50%–60%;

Figure 1 ), although direct comparison is not possible because different methods of data analysis and presentation were used. Nonetheless, it is possible that the guideline components assessed and intervention, patient, and system factors all contribute to potential differences. It is also to be expected, given our method of relying on the best available data, including accounting for patient self-report of adherence, that rates would be somewhat lower.

It is noteworthy that guideline concordance rates in both trials, as well as in both arms in this trial, declined over time. Since there are no other guideline concordance data for follow-up periods longer than 1 year, we cannot know whether this is atypical. However, it is not unexpected given the pattern of inconsistent patient adherence over time in bipolar disorder

(35,

36), and it represents an area of challenge for researchers, clinicians, and our patients.

The finding that a multicomponent intervention tested in an effectiveness design can result in significant and sustained improvements in guideline concordance gives reason for hope and direction for further work, particularly since improvements in concordance may be associated with improvements in outcome for bipolar disorder

(10) . Given that CSP 430 demonstrated significant effects on weeks of mania or hypomania, weeks in affective episode, overall functional outcome, and mental quality of life

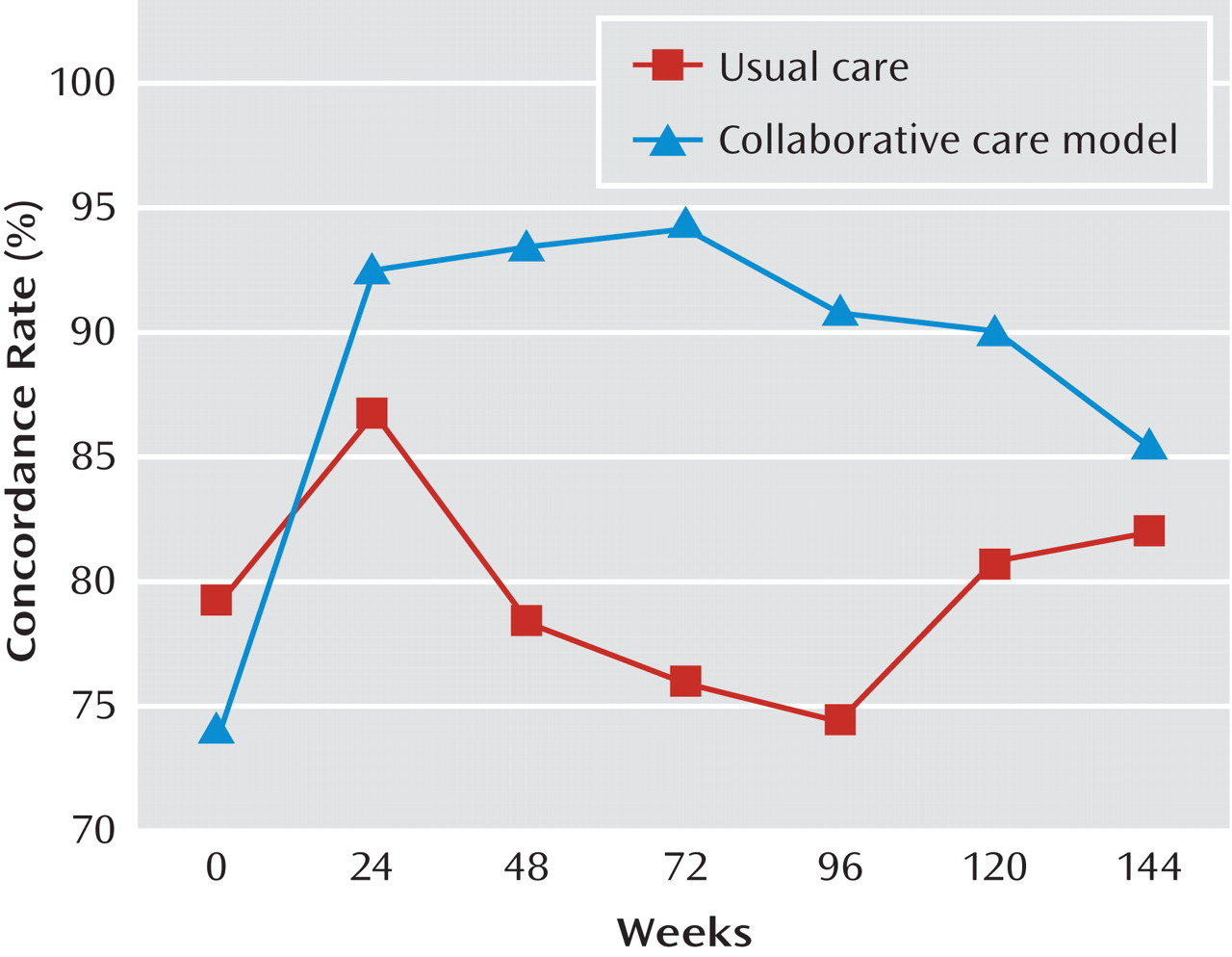

(26), it is reasonable to propose a straightforward mechanism for collaborative care effects: implementation of the guideline-enhancement component of the collaborative care model → improved antimanic treatment guideline concordance → reduced weeks of mania or hypomania → reduced weeks in affective episode → improved social functioning → improved mental quality of life. However, this simple model remains speculative, despite its intuitive sense, since multicomponent interventions may work via multiple mechanisms. Intriguingly, indirect evidence suggests that the most difficult step in establishing guideline-concordant treatment is to establish and maintain any antimanic treatment rather than to achieve therapeutic levels or doses once an agent is administered, since the vast majority of those receiving any antimanic treatment received guideline-concordant treatment (

Figure 2 versus

Figure 1 ).

It is not clear whether enhanced guideline concordance requires a collaborative care approach of the specific type tested here. In fact, given the results of the Texas Medication Algorithm Project study, it is likely that this approach represents a family of methods that includes components to enhance patient, provider, and system elements of care. The most salient next question is that of which components of collaborative care models are responsible for the improvements in health outcomes seen with such multicomponent interventions

(10,

25 –

28) .

There are several limitations to this study. The trial was carried out with a sample of predominantly male veterans who consented to participate in a treatment trial and were treated in the VA health care system. However, the sample was representative of the population from which it was drawn and was clinically complex and severely impaired

(25,

30,

31) . Moreover, as health care systems move toward more integrated delivery systems and more measurement-based care under any funding system, lessons from the VA health care system should become even more relevant. Nonetheless, results cannot be directly generalized to other systems and populations, such as populations with more women and less severely ill individuals. However, clinical outcome results were replicated using a similar collaborative care model tested in a population-based, less severely ill sample in a commercial health maintenance organization

(27) ; while we do not know from that trial whether collaborative care had a similar impact on process measures such as guideline concordance, there were similar effects on clinical outcome. The manner of data collection did not permit specification of not-to-exceed levels or dosages for medications and did not address episode-specific treatment or toxicity (e.g., hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia). However, it is unlikely that collaborative care (which, in addition, emphasized patient education and access in order to facilitate clinical management) was associated with unmeasured medication-related psychiatric or medical toxicity, since the clinical trial demonstrated that the collaborative care model improved clinical outcome, functioning, and quality of life without any difference in all-cause direct treatment costs

(26) . Finally, there are many other guideline monitoring points that could have been chosen for analysis (

Table 1 ). We chose to focus on a component that was supported by a strong and consistent evidence base

(7), that represented a known problem area

(3), and that was likely to be associated with the strongest clinical effect with collaborative care, namely, reduction of time in mania

(26 (27) . Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that other guideline parameters would not have shown similar improvements in concordance under collaborative care.