Although the Feighner criteria have had an immense influence on the development of psychiatry in the United States and around the world, the documentation of their development has been limited to a brief commentary by Feighner (

2) and a difficult-to-obtain collection of commentaries by a dozen authors (

3). A more detailed examination is needed. Many of the primary contributors to this effort, notably Eli Robins, Sam Guze, George Winokur, and John Feighner, are deceased. Our ability to reconstruct the key events in the development of the criteria is critically dependent on the memory of two of us—G.M. and R.M.—who were directly involved with the events described below. K.S.K. initiated this effort, organized the material, and wrote the initial draft of this article.

The Historical Context

In the 1940s, as a result of several historical processes, Freudian psychoanalytic theory and practice came to dominate American psychiatry. By the mid-1950s, nearly every department chairman of psychiatry in the United States was an advocate of psychoanalysis. In the higher-prestige residency training programs, trainees were typically expected to undergo a personal psychoanalysis as a part of their training.

At that time, psychoanalysts generally had a negative view of psychiatric diagnosis, arguing that diagnosis in the conventional sense could be injurious to patients. Early empirical investigations of psychiatric diagnoses, beginning with Ash in 1949 (

4) and reviewed by Beck in 1962 (

5), showed that the probability of agreement of two psychiatrists in diagnosing mental disorders in patients hardly exceeded chance. Wilson (

6) recounts the efforts of APA to convene, in 1953, a 3-day "Conference on the Development of a Research Program for the Evaluation of Psychiatric Therapies":

The goal of the conference was ambitious: to develop a "comprehensive evaluation of therapies" and to establish "sound criteria, methodology, or standards under which such validation might take place." The conference ended with the frank admission that efficacy of treatment was impossible to judge because of the lack of standardized criteria for both diagnosis and treatment outcome. (p. 403)

G.M. recalls: "That was a disastrous state of affairs in a discipline trying to become a science. Nobody appeared concerned."

In the mid-1950s, the Department of Psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis was nearly alone among the major departments of psychiatry in the United States in standing apart from this trend. The chair of Psychiatry and Neurology at Washington University at that time was Dr. Edwin Gildea, a scholarly man interested in biological theories of psychiatric illness and skeptical about the Freudian viewpoint (

7). He believed in open-minded inquiry and in the importance of supportive evidence. He assembled around him, in the early to mid-1950s, a like-minded faculty.

Dr. Eli Robins came to the department in 1949 from Harvard. His immediate goal was not to teach psychiatry but to learn a new technique in chemical microanalysis just being developed in the Department of Pharmacology at Washington University. He had been exposed to psychoanalysis under Dr. Helena Deutsch but considered it "silly." He had also been exposed to systematic clinical investigation under Dr. Mandel Cohen, a Boston psychiatrist interested in psychiatric diagnosis. Both acolyte and mentor were firmly of the opinion that in the absence of replicable evidence, no truth claim had any validity at all.

Dr. Cohen, an important influence on the development of the Feighner criteria, had, in the late 1940s to the mid-1950s, enlisted psychiatric residents to participate in systematic interview studies aimed at describing and delineating the natural history of common psychiatric disorders. These disorders included "anxiety neurosis" (

8), hysteria (

9,

10), and manic-depressive disease (

11). The clinical orientation and methodology that Robins brought to Washington University was shaped by his experiences with Dr. Cohen.

Dr. George Winokur also arrived at Washington University in 1950, as a third-year psychiatric resident. He came from Johns Hopkins, where, perhaps because of the strong Meyerian tradition there, he escaped strong Freudian influences. As G.M. recalls:

He shared our dismissal of claims that lacked evidential support. He was interested in the theoretical aspects of psychiatry but only to the extent that the proposals were testable. He was enthusiastic about clinical training and encouraging the research interest of the psychiatric residents and younger faculty.

Dr. Samuel B. Guze came to Washington University first as an undergraduate and then as a medical student. He trained in internal medicine and then, while a faculty member in medicine, began his psychiatric training at Washington University in 1950 and joined the Department of Psychiatry as a faculty member in 1955 (

12). G.M. recalls that "Sam was intense and highly organized. He was a dedicated educator and highly skilled administrator." G.M. joined the department on completion of his residency training in psychiatry in 1957.

The zeitgeist of the Washington University Department of Psychiatry at this time is well captured by this recollection of G.M.

Concern for stable and reliable diagnosis was never far from our thoughts. During my final year of residency (1956–57), Eli had invited me to join him in a systematic study of suicide. The methodology followed that of Mandel Cohen: a mimeographed booklet provided all the questions to be asked of each informant (spouses, family members, associates, friends, family physicians). Their responses were to be recorded verbatim in the booklet. Freudians scoffed: Was not free association the royal road to the unconscious? Our method was "too mechanistic." Eli and I analyzed the interview data independently. Disagreements in diagnosis were resolved, or not, based solely on the evidence at hand. Authority had no place in the deliberations. Eli introduced the diagnosis of "undiagnosed" to circumvent inadequately documented choices. The result of the data analysis was a clear picture of who commits suicide and under what conditions. Nearly all (95%) had been diagnosably psychiatrically ill at the time of their deaths. Moreover, two psychiatric illnesses accounted for two-thirds of the cases: major depression in nearly half, and substance abuse in about one-fourth. We had employed explicit criteria for the diagnoses. That was a first in American psychiatry.

The fate of the article Robins and colleagues wrote on that study is illustrative of prevailing attitudes of American psychiatry at that time. G.M. continues:

How bad was the rejection of diagnosis? We submitted a paper to the

American Journal of Psychiatry describing the suicide findings. Clarence Farrar, himself a supporter of psychoanalysis, was Editor in Chief. He reluctantly accepted our offering, but

personally expunged nearly all diagnostic terms from the text. That robbed the paper of its significance and utility. Not to be outmaneuvered, Dr. Robins inserted the diagnostic terms into the legends for figures accompanying the text and footnotes and thus retained the message linking specific psychiatric illnesses to their outcome (

13). A companion paper we submitted to the

American Journal of Public Health (

14) encountered no such discrimination.

Wilson (

6) recounts the following congruent recollection from Robert Spitzer:

[At] APA annual meetings in the 1960s, the academic psychiatrists interested in presenting their work on descriptive diagnosis would be scheduled for the final day in the late afternoon. No one would attend. Psychiatrists simply were not interested in the issue of diagnosis. (p. 403)

The development of the Washington University zeitgeist and the key role Eli Robins played in it is summarized in this quotation from Sam Guze (

12, p. 3):

During the early 1950s there really was no focus of idea generation in the Department of Psychiatry except for Eli Robins and George Winokur and me. I do not think we had a model when we started, but as we talked and talked and talked the outlines of the model grew as to just what the Department of Psychiatry ought to be. We went to Ed Gildea, the department head, and he laughed and rubbed his head and essentially said, "Well, if you want to try it go ahead." So we divided up responsibilities for the teaching. We put a lot of emphasis on research. We started insisting at that point that every resident would have a research rotation. Now once 1955 came around we really began to exert gradual control and we made Ed Gildea nervous because he was getting criticism about us, but he did not know what to do about us. Intellectually he could not really fault us, and it was an example of if you have a plan you are way ahead of the guy that does not have a plan. So Eli and Winokur and I met and talked, and we said, "Okay, we're going to have a department in which the keystone of education for medical students and residents is going to be to learn about diagnosis, to learn about the natural history of psychiatric disease, to learn about differential diagnosis, and we will encourage a broad ranging kind of research—clinical, neurochemistry, epidemiology." I owe to Eli opening up to me that whole field of literature. No one had taught me about that literature; Eli was the one.

The Development of the Criteria

John Feighner arrived as a resident at Washington University in 1966, 1 year behind R.M., who recollects:

In those days, the department had a number of papers that were obligatory reading for all the residents. John first came in 1967 with the proposal that a paper be published citing and reviewing those papers that clearly outlined the scientific and diagnostic bases for research in psychiatry. Drs. Robins, Winokur, and Guze were enthusiastic about the idea and proposed meeting to discuss it. Dr. Woodruff, then a junior faculty member, was invited as a highly regarded future leader of the department. I was invited because by then I was planning with Dr. Robins a large study of patients attending a psychiatric emergency room. At the first meeting there was agreement that the concepts expressed so far were often incomplete or vague, that much had to be rewritten and expanded, and that the paper would be more complex than initially intended.

The change in perspective and scope [from the original goal of a literature review to the decision to develop new criteria] was gradual. An example was the criteria for depression. Though everyone was initially satisfied by the thinking presented by Cassidy et al. (

11) in 1957, further examination led to new questions, changes, eliminations, and additions. This change was progressive and occurred with the full participation of everyone. Every change was made by consensus. I do not recall any vote because of disagreements. Everyone was taking notes, including me.

The criteria for depression were the first we discussed. When we finished with these criteria, it was clear that the same would be done with other diagnoses, and the process would be much longer than anticipated. In a typical fashion, the papers with the original criteria were discussed, and then the long process of discussion, modification, and addition of new perspective would begin and end before another diagnosis would be considered. A number of people in the department made "cameo appearances" at Dr. Robins's call, mostly to deal with specific subjects. Those I remember the most are Dr. Lee Robins [wife of Eli Robins], Dr. Hudgens, and Dr. Murphy.

The meetings occurred at irregular intervals, between each week and once or twice a month. They were in Dr. Robins's office, and he was clearly in charge. Dr. Feighner acted as a very active coordinator and provider of new information needed by the group. Drs. Robins, Winokur, and Guze were enormously generous with their time, their ideas, and their willingness to look further on matters that needed more thinking. Even though John Feighner was a junior resident, he was very proactive, inquisitive, enthusiastic, and not afraid to question anybody's thinking. As I remember, all the meetings were attended by the six coauthors; every effort was made to schedule the meetings so as to assure everyone's attendance. The only other people there would be Dr. Robins's secretaries.

Feighner recalled that the meetings lasted for approximately 9 months and that he was responsible for doing a "comprehensive literature review ... and a working outline of diagnostic criteria" for each disorder. The committee (the six coauthors) "would then meet, review these criteria, and upon the basis of their own research and understanding of ongoing studies and after review of the available data, these criteria were revised and then finalized" (

3, p. 8).

In the following sections, we attempt to reconstruct, as far as possible, the background and thinking of the developers of the Feighner criteria for three of their proposed categories—depression, antisocial personality disorder, and alcoholism—in some detail. We also comment on factors involved in the development of five other sets of criteria.

Depression

Of the diagnoses for which Feighner et al. proposed criteria, the prior historical precedents are clearest for major depression. Robins had been strongly influenced by the work of Cohen, whose group published a detailed clinical study of "manic-depressive disease" in 1957 (

11). Dennis Charney, who has been interested in the historical origins of the Feighner criteria for depression (personal communication, March 24, 2009), called John Feighner in 1980. Feighner reported that he "relied a lot on an article by Cassidy." The criteria for depression outlined in the Cassidy et al. article were as follows: "the patient (a) had made at least one statement of mood change ... and (b) had any 6 of the 10 following special symptoms: slow thinking, poor appetite, constipation, insomnia, feels tired, loss of concentration, suicidal ideas, weight loss, decreased sex interest, and wringing hands, pacing, over-talkativeness, or press of complaints." Charney then located Cassidy, who was retired and living in Florida. When asked how he decided on the threshold of six out of 10 criteria, Cassidy replied, "It sounded about right."

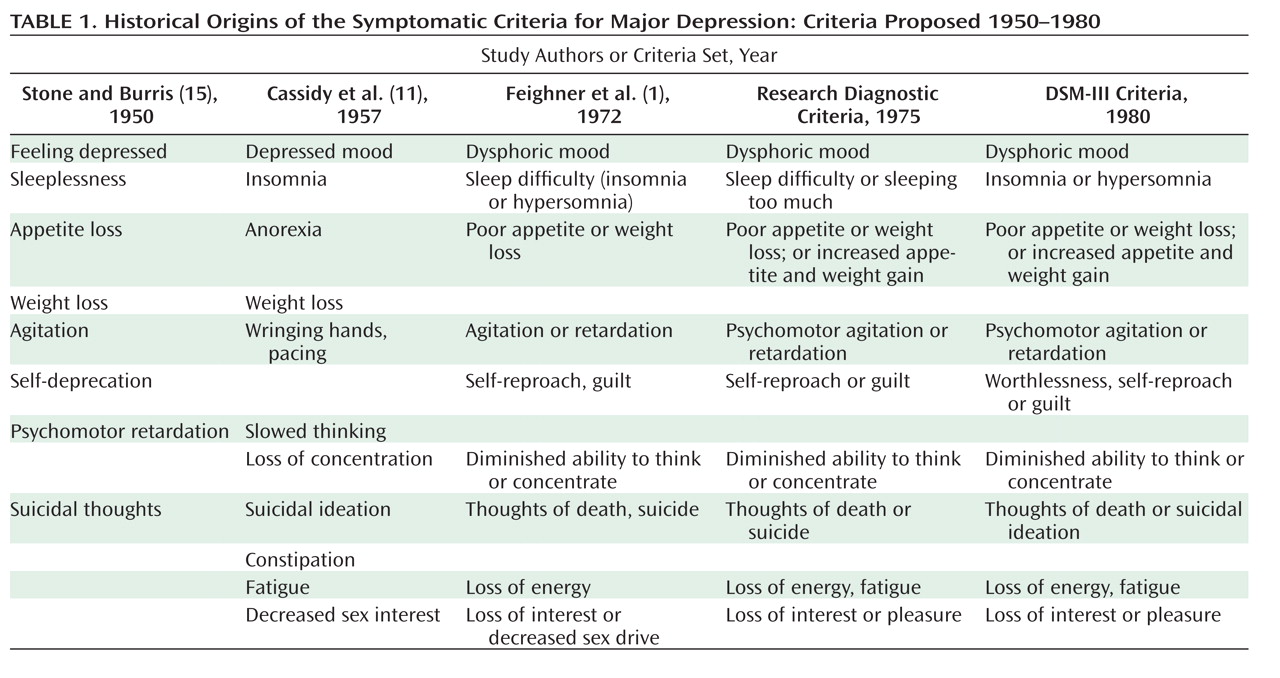

The proposed Feighner criteria were very similar to those utilized by Cassidy et al. (

11) (

Table 1). Four significant changes were made: constipation was dropped; feelings of self-reproach or guilt were added; insomnia was expanded to sleep difficulties, which included hypersomnia; and anorexia and weight loss were combined into one item. R.M. recollects the following:

Eliminating constipation was the result of Dr. Robins's thinking: Constipation was common among depressed patients, but lacked specificity. Most constipated people are not depressed. The initial criteria were tilted toward "physical" rather than "emotional" manifestations. Everyone agreed that adding self-reproach or guilt produced a more balanced and realistic set of criteria. Besides, "guilt" was prominent in all the surveys. Hypersomnia was also often mentioned in surveys, especially among depressed people who were gaining weight or slowed down. We came to see anorexia and weight loss as two sides of the same coin.

In trying to clarify the origins of the criteria employed by Cassidy et al. (

11), we reviewed the report they cited by Stone and Burris published 7 years earlier (

15). In addition to the assumed requirement of sadness, five of the key symptomatic criteria for depression included in the Feighner criteria (and which were carried through all the way to DSM-III—insomnia, anorexia/weight loss, agitation/retardation, self-reproach, and suicidal ideation) are all noted in this 1950 report (Table 1) (

15). There the trail peters out. If any other earlier explicit diagnostic criteria for depression exist that contributed to those proposed in the Feighner criteria, they have eluded our search.

Antisocial Personality Disorder

The starting point for the development of the Feighner criteria for antisocial personality disorder was the 19 criteria developed for sociopathic personality by Lee Robins and validated in her 1966 follow-up study (

16). Eight of the nine Feighner criteria for antisocial personality disorder had close parallels with these criteria. Two research projects involving antisocial personality disorder were then under way at Washington University involving prisoners (

17) and patients seen in an emergency department (

18–

20). While we cannot fully recreate the rationale for the specific Feighner criteria for antisocial personality disorder, R.M. recalls that in discussions the group was particularly concerned about avoiding confounds with poverty and drug abuse. This would explain the elimination of three of the 19 Robins criteria ("excessive drugs," "heavy drinking," and "public financial care"). With a focus on the problems of differential diagnosis, there was also a concern that some of the Robins criteria, such as "lack of friends," "impulsive behavior," "suicide attempts," and "many somatic symptoms," would be too nonspecific, and others, such as "lack of guilt," too difficult to evaluate reliably. The one criterion included in the Feighner criteria for antisocial personality disorder that was not in the Robins criteria ("running away from home") was empirically evaluated by Guze and Goodwin and found to be good at distinguishing individuals whose diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder was confirmed on follow-up from those whose was not (

21). These discussions may also have made use of the extensive data on the frequency of these symptoms in sociopathic individuals, other psychiatric patients, and comparison subjects presented in Robins's monograph (

16). For example, on inspection it is clear that the more frequently the individual criteria occurred in the group of sociopathic individuals in Robins's monograph, the more likely they were to be included in the Feighner criteria.

Alcoholism

The criteria for alcoholism were especially influenced by Guze. R.M. recalls:

He did a lot of his work in outpatient clinics where a number of patients had findings of "deviant drinking" so that many had a limited history of driving while intoxicated, passing out after drinking, or fighting. Most of the patients with a limited history did not have a chronic, deteriorating course. Dr. Guze wanted to have the diagnosis of alcohol addiction limited to those whose history suggested strongly the destruction of their lives by alcohol.

Indeed, the origins of the Feighner criteria for alcoholism can be traced to a 1962 study by Guze et al. on the prevalence of psychiatric illness in criminals (

22). That study employed an interview that included 20 criteria for alcoholism that were based in part on the prior work of Jellinek (

23). These criteria were organized into five groups, symptoms from at least three of which were required for a diagnosis. Individuals who met these criteria were more likely to have a family history of alcoholism and, in a 3-year follow-up (

24), had higher recidivism rates. In interviews conducted 8–9 years later, 74% of those originally diagnosed as alcoholic received the same diagnosis (

25).

The Feighner criteria for alcoholism—which contain four symptom groups—are closely related to those published in 1962 (

22), the major difference being the elimination of the three criteria making up group 2 ("drinking every day," "drinking the alcohol equivalent of 54 ounces of whiskey per week," and "unable to answer questions about alcohol consumption—interpreted as evasiveness."). The rationale for this change was outlined in their second follow-up paper (

25, pp. 585–586):

In the original study, the criteria for alcoholism included items concerning frequency and quantity of drinking. Further experience indicated that the reliability and validity of the data concerning frequency or quantity of drinking were hard to establish. On reviewing the 96 index cases who received the diagnosis of alcoholism, it was found that items dealing with frequency and quantity of drinking could be omitted without affecting the diagnosis. Such items, therefore, were excluded from consideration in subsequent alcoholism diagnoses.

With virtually no change, groups 3, 4, and 5 from the 1962 report became groups 2, 3, and 4 of the Feighner criteria. Slight changes were made to the criteria of group 1 from the 1962 report to make up group 1 for the Feighner Criteria.

Other Diagnoses

The Feighner criteria for schizophrenia required "at least 6 months of symptoms ... without return to the premorbid level of psychosocial adjustment." The symptomatic criteria were very simple. Only delusions, hallucinations, or thought disorder was required. The major influences here were Eli Robins and Sam Guze. R.M. recalls:

The point of departure in Dr. Robins's thinking was that schizophrenia was a deteriorating disorder. Dr. Robins, a student of Wing, Schneider, Leonhard, Fish, and others, became convinced that the symptoms they addressed had no prognostic value and were often seen in affective disorders with psychosis. As for "flat affect," he thought this was mostly an impression by some examiners. Dr. Robins thought schizophrenia could be diagnosed only in patients who had had symptoms for a long time and were presenting manifestations of social and occupational deterioration. He insisted that the course of the illness was much more important than the character of the delusions and hallucinations.

In the second follow-up of his criminal cohort (

25), Guze and his colleagues also assessed symptoms of schizophrenia, which they described in terms similar to those eventually adopted in the Feighner criteria:

This diagnosis was used as described by Langfeldt (

26) and Stephens et al. (

27) to refer to a chronic, frequently progressive disorder characterized by an insidious onset, poor prepsychotic adjustment, prominent delusions or hallucinations, severe disability in interpersonal relationships and job performance, minimal, if any, affective symptoms, and a clear sensorium. (

25, p. 585)

The only published precedent we were able to find for the Feighner criteria for mania was a 1967 paper by three Washington University faculty members who were not directly involved in the development of the criteria (

28). Of the seven symptomatic Feighner criteria for mania, five were proposed by Hudgens et al. (

28).

The Feighner criteria for hysteria were substantially influenced by a series of studies done by Robins and Cohen and published in the early 1950s (

9,

10,

29). One of these studies compared symptoms in 50 women with a clinical diagnosis of hysteria and 50 healthy comparison subjects (

9). Thirty-nine symptoms were noted to be significantly more common in the women with hysteria, and 32 of them made their way into the Feighner criteria. With the exception of two additional symptoms in group 2, all of the individual Feighner criteria for hysteria were used in a 1962 study by Perley and Guze (

30), which showed 90% diagnostic stability among individuals meeting these criteria when followed up over a 6- to 8-year period, and in the 1969 follow-up paper by Guze et al. (

25).

The Feighner criteria for drug dependence—consisting of only three criteria—were identical to those used in the 1969 follow-up of the criminal cohort (

25). This same paper also outlined diagnostic criteria for obsessive-compulsive neurosis—based on the work of Pollitt (

31)—which closely resembled those proposed in the Feighner criteria. For example, the decision in the Feighner criteria to exclude individuals with obsessive-compulsive symptoms in the setting of depression or schizophrenia follows the approach used by Pollitt.

The Influence of the Feighner Criteria

The Research Diagnostic Criteria and Toward DSM-III

Feighner and colleagues' "Diagnostic Criteria for Use in Psychiatric Research," which proposed criteria for 14 psychiatric disorders, was published in January 1972 (

1) in the

Archives of General Psychiatry. Fatefully, the Clinical Studies Committee of the Collaborative Program on the Psychobiology of Depression began work that year on the construction of diagnostic criteria and a clinical interview to standardize the assessments to be performed across the multiple sites of this program (

32). Robert Spitzer (personal communication, July 13, 2009) was in charge of that effort and recalls being called by Martin Katz, Ph.D., who helped direct the entire study. Dr. Katz suggested that Dr. Spitzer should collaborate on this effort with Eli Robins and colleagues at Washington University who had recently published the Feighner criteria. Spitzer recalls making six visits to Washington University, probably from 1972 to 1974, during which time he and Jean Endicott worked with Robins on the development of the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (

33,

34). Dr. Endicott (personal communication, July 16, 2009) commented on the intensity of these meetings. "Spitzer and Robins were both strong minded and passionate about psychiatric diagnosis. And yet, at the end of the day, we were nearly always able to reach a consensus."

Drs. Spitzer and Endicott concluded that they learned three major lessons from their interactions with Robins and the Feighner criteria that deeply shaped their subsequent efforts with the RDC and DSM-III. The first was to use operationalized criteria. While they had seen drafts of inclusion and exclusion criteria for individual disorders that were used for particular studies, the idea of developing a set of criteria for many disorders and for widespread use was a novel and, ultimately, very attractive idea for them. Using the Feighner criteria and the RDC as a precedent, Spitzer was able to convince the DSM-III task force to use operationalized criteria throughout DSM-III. A single dissenter argued that operationalized criteria should be used for research only.

Second, up until their contact with Robins and the Feighner criteria, the focus of the diagnostic work of Spitzer and Endicott had been on presenting symptoms and signs. As Endicott put it, "They were the first to tell us that we had to pay attention to more than the acute clinical picture. In defining disorders, we also had to be concerned with the course of illness and prognosis."

Third, as Spitzer and Endicott substantially expanded the number of disorders in the RDC beyond those considered in the Feighner criteria, Robins kept asking, in a persistent and skeptical manner, "What is the evidence?" They came to appreciate, as a result of these interactions, the importance of basing diagnostic criteria, wherever possible, on data rather than solely on clinical wisdom. Tellingly, a footnote on the front page of the Research Diagnostic Criteria (

33) states, "These diagnostic criteria are an expansion and elaboration of some of the criteria developed by the Renard Hospital Group in St. Louis, Mo."

Citation Analysis

As of July 20, 2009, the Feighner criteria paper has been cited 4,731 times (data from Thomson Reuters, ISI Web of Knowledge, 2009). Of these citations, 63.4% (N=2,998) originate from first authors in the United States. However, the international influence of this article is indicated by the countries from which the next largest numbers of citations originate: England (N=433), Canada (N=288), Germany (N=221), Australia (N=87), and France (N=79). Based on the Web of Science subject areas, 71.2% of these citing publications were in psychiatry. But large numbers of citations originated from other fields, which were, in descending order of frequency, psychology, neurology, neurosciences, and pharmacology. The ten most common institutional affiliations of the first author of the citing papers were Washington University (7.6%), University of Iowa (6.9%), New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University (4.6%), Harvard University (4.2%), University of California at San Diego (3.2%), University of Pittsburgh (3.0%), Yale University (2.6%), National Institute of Mental Health (2.5%), University of Texas (2.1%), and University of Washington (2.1%). The Feighner criteria have been used widely by leading psychiatric research centers throughout the United States.

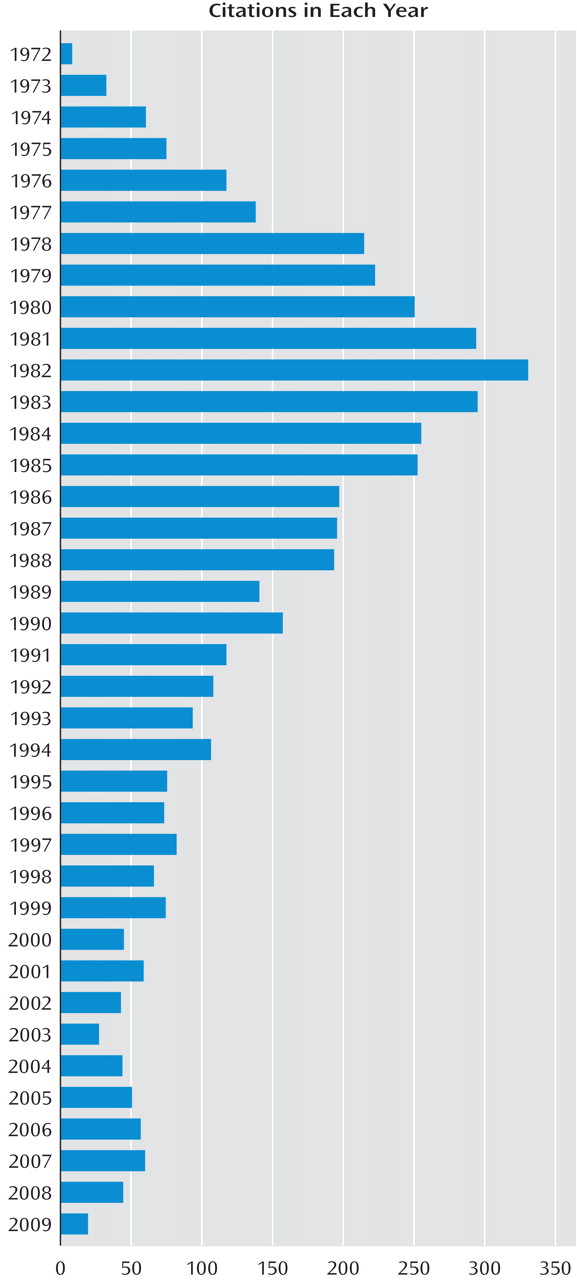

The temporal pattern of citations, shown in

Figure 1, depicts a rapid upswing in frequency of citation from 1972 to 1977. During this period, the RDC were being developed, and then published, and work on DSM-III had begun. G.M. recalls that "within 2 years [of publication of the Feighner criteria], the impact on the quality of research papers published in the U.S. was evident. We were now all speaking the same language! That had been the purpose of our efforts."

After a year's pause, another rapid upswing to over 300 citations a year occurred from 1979 to 1982. This period included the publication of DSM-III in 1980. From 1982 until the present, we see a general slow decline in the citation rate. The decline levels off around 1987 when DSM-III-R was published. A small increase in citations is seen in 1994 when DSM-IV was published. Interestingly, the citation rate moderately increased for the 4 years from 2004 through 2007.

Discussion

We have tried to summarize the historical context within which the Feighner criteria arose, clarify the development of these criteria, and examine their impact on the subsequent course of American psychiatry.

The historical record shows that the small group of individuals who created the Feighner criteria instigated a paradigm shift that has had profound effects on the course of American and, ultimately, world psychiatry. We concur with Spitzer and Endicott regarding the three lasting contributions of the Feighner criteria. First, they introduced for the first time the systematic application of operationalized criteria into psychiatry. As is common in important intellectual developments, the Washington University researchers were neither the first nor the only ones to apply operationalized criteria to psychiatric disorders. Others had proposed operationalized criteria for major depression in the early 1950s (

11,

15). The Present State Examination, developed by John Wing in the 1960s in the United Kingdom, contained a form of operationalized diagnostic criteria (

35), as did the DIAGNO computer program for DSM-II diagnoses developed by Spitzer and Endicott during the same period (

36). The philosopher Carl Hempel advocated the use of "operational definitions" in an address to the American Psychopathological Association in 1959 (

37) (although both R.M. and Spitzer deny that Hempel had any impact on the development of, respectively, the Feighner criteria and the RDC). Operationalized criteria had been published and empirically evaluated for several rheumatologic disorders from the 1940s into the early 1970s (

38–

41). R.M. considered it likely that particularly Guze, with his training in internal medicine, was aware of these developments. However, the development of the Feighner criteria represents the first systematic implementation of this methodology in psychiatry.

The developers of the Feighner criteria were conversant with the conceptual issues involved in the use of operationalized criteria. A few years after the publication of the criteria, Guze gave a thoughtful description of taxonomic principles and their application to psychiatry and medicine (

17). Showing wide knowledge of the relevant literature in biology and medicine, Guze noted the difficulty in applying essentialist or monothetic diagnostic models to psychiatric illness because psychiatric disorders can rarely be defined by single, pathognomonic features. Rather, he argued, like many categories in nature, psychiatric disorders typically share a substantial proportion of their symptoms and signs but do not necessarily agree in any single property. This polythetic model of illness is well captured by operationalized diagnostic criteria, which, he suggested, are particularly well suited for psychiatric disorders.

Second, the developers of the Feighner criteria brought back to American psychiatry an emphasis on course and outcome as a critical defining feature of psychiatric illness. This had been a feature of one major strand of European descriptive psychiatry culminating in the work of Kraepelin (

42,

43).

Third, the Feighner criteria can be best understood as part of a broad research program the goal of which was to develop psychiatric diagnoses that were based on empirical data. This approach was clearly articulated in a famous article from this group, published 2 years before the criteria, that proposed a set of validating criteria for psychiatric disorders (

44). In this article, they set out a research program to evaluate the validity of psychiatric disorders emphasizing, in particular, follow-up and family studies. They not only articulated these ideas, but the developers of the Feighner criteria, with many colleagues, embarked on a wide range of empirical studies seeking to validate many of the categories in the criteria (see, for example, references

16–

20,

22,

24,

25,

30,

45–

51).

The relative role of empirical data as opposed to informed clinical opinion in psychiatric nosology has remained controversial in the development of subsequent diagnostic systems in American psychiatry, including DSM-V. However, while informed by data and sharp clinical intuition, most of the key features of the Feighner criteria were not directly based on systematic empirical study. For example, to the best of our knowledge, the developers of the criteria had not conducted studies to examine specifically the validity of such key features as the proposed cutoff of five of eight criteria for definite depression, a 6-month duration for schizophrenia, or the need to meet criteria in three of four symptom groups for definite alcoholism. The decisions to add or subtract criteria, while often empirically informed, were not typically based on studies that specifically evaluated the alternative diagnostic approaches being considered—although such an approach was used when dropping from the criteria for alcoholism items that assessed the frequency and quantity of drinking (

25). The authors of the Feighner criteria were aware of the preliminary nature of their efforts and noted that "all [these] diagnostic criteria are tentative in the sense that they [will] change and become more precise with new data" (

1, p. 62).

One way to judge the importance of the Feighner criteria is to consider what would have happened to the course of American psychiatry if they had never emerged. Bob Spitzer, whose contributions made him particularly well placed to address this question, concluded: "The effect would have been big. Operationalized criteria would have probably emerged, but it would have been years later and probably in a less systematic form. DSM-III would have been delayed and would likely have looked quite different."

We do not wish this to be triumphalist history. There is, we suggest, a healthy dialectical tension between nomothetic (law-based) and ideographic (individual case) approaches to psychiatry and between scientific explanation and psychological understanding. When work on the Feighner criteria began, American psychiatry had lurched badly to one side of this dialectic. Diagnostic thinking was discouraged and with it a whole range of scientific questions that depended on reliable diagnosis. The renewed interest in diagnostic reliability in the early 1970s—substantially influenced by the Feighner criteria—proved to be a critical corrective and was instrumental in the renaissance of psychiatric research witnessed in the subsequent decades. However, neither we nor, we think, the developers of the criteria would claim that assessing operationalized diagnostic criteria is all there is to a good psychiatric evaluation. While critical, a diagnosis does not reflect everything we want to know about a patient. Our diagnostic criteria, however detailed, never contain all the important features of psychiatric illness that we should care about. That said, the task of developing reliable and valid psychiatric diagnoses will, we predict, remain central to the clinical and research mission of psychiatry for the foreseeable future. The shape of that historical journey was deeply influenced by the Feighner criteria and the small group of psychiatrists at Washington University who developed them.