Western medicine is struggling to keep up with the catastrophic effects of the western diet. Substantial durable dietary changes at the individual level are exceedingly difficult. Food intake habits are influenced by a complex array of factors. Eating is perhaps the quintessential biopsychosocial behavior, and mounting data suggest its central importance in the overall health of our patients. Obesity has been identified as a priority area by the National Institute of Mental Health, and studies have demonstrated that more healthful eating patterns are associated with better cardiovascular health (

1,

2). We currently lack data from randomized, controlled trials to demonstrate the efficacy of healthful eating on psychiatric disorders. However, a growing body of epidemiologic evidence supports a relationship between nutrition and mental health. Manifestations of nutritional deficiencies include psychiatric symptoms, and single nutrients such as omega-3 fatty acids and folate have received attention in epidemiologic and treatment studies targeting mental health (

3,

4). Now, new evidence is emerging regarding specific food intake patterns and risk of depression.

In this issue, Jacka et al. (

5) present data regarding the association of dietary patterns with depression and anxiety. Jacka and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study in Australia in which adult women were randomly selected. A comprehensive food frequency questionnaire was developed to reflect 12-month eating habits, and it was administered to each subject. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR was utilized to assess psychiatric disorders, with particular focus on major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and anxiety disorders. The 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) was also used to quantify psychiatric symptoms. Covariates, such as socioeconomic status, education, physical activity, alcohol and tobacco use, and body mass index, were also recorded.

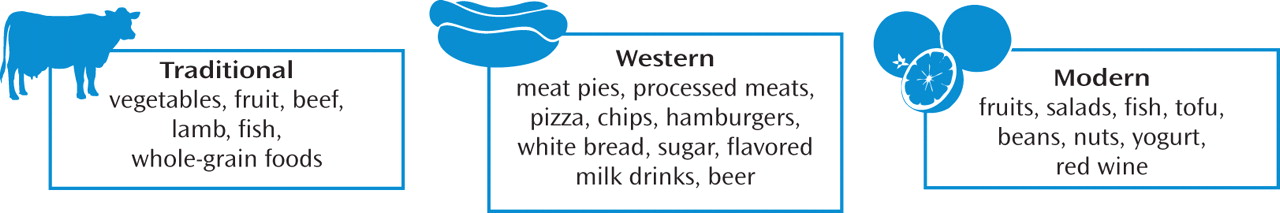

Diets were categorized into three types: traditional, western, and modern (

Figure 1). A separate diet quality score was calculated on the basis of Australian national nutrition guidelines: "This scoring method assigns points for the consumption of desirable foods at the recommended levels; for example, a point is assigned for the consumption of at least two servings of fruit a day, at least five servings of vegetables per day, red meat consumption one to five times per week, using low-fat dairy products, and using high-fiber, whole-grain, rye, or multigrain breads. In addition, a maximum of two points was assigned for alcohol consumption at the recommended levels."

The authors found that the western diet was associated with higher GHQ-12 scores, although no relationship was found between GHQ-12 score and either the traditional or modern diet. A traditional diet was associated with a lower risk of a diagnosis of depression or anxiety, and a western diet was associated with a higher rate of depressive disorders. Higher diet quality scores were associated with lower GHQ-12 scores.

Two prospective cohort studies from Spain (

6) and the United Kingdom (

7) also provide information regarding the relationship between depression and patterns of nutritional intake. In the Spanish study (

6), the Mediterranean dietary pattern was found to confer protection against the development of depression. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet was categorized into quartiles, with incremental increases in risk for depression associated with lower adherence. Particular inverse associations with incident depression were noted with higher consumption of fruit, nuts, and legumes, as well as a higher ratio of monounsaturated to saturated fatty acids. In the U.K. study, a dietary pattern containing higher amounts of processed foods was associated with a higher risk of subsequent development of depressive symptoms (

7). Dietary patterns were assessed for "whole foods" (with fruit, vegetables, and fish characteristic of intake) and processed foods (largely represented by processed meat and bread products and high-fat dairy products). After adjustment for confounding variables, persons in the group with the highest intake of whole foods had the lowest rate of depressive symptoms on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale. In addition, a study from France demonstrated an association between the metabolic syndrome and depression (

8).

It is both compelling and daunting to consider that dietary intervention at an individual or population level could reduce rates of psychiatric disorders. There are exciting implications for clinical care, public health, and research.

It has been previously emphasized in the epidemiologic literature that "we do not eat nutrients, we eat foods…in certain patterns" (

9). These patterns are influenced by cultural and environmental factors, including availability and accessibility of foods, ability to buy and prepare them, marketing, and educational efforts to foster healthy dietary intake (

9).

Implications for the Patient You Are Seeing Today

It is practical to include nutritional habits and weight history in patient assessments. Dialogue with patients about what they eat and associated factors may enhance our ability to provide medical monitoring and advice. Inquiry about nutritional habits can give us a window into the socioeconomic and social circumstances of our patients. The inquiry itself conveys to patients that we consider their overall health a priority. Children are dependent on others for food accessibility and availability. For many of our patients, households may be the smallest units for targeted nutritional changes.

Implications for the Population and Public Policy

Since purposeful change of dietary habits at the individual level is exceedingly difficult, policies and educational efforts at the community and national levels are important. Successful shifting of nutritional intake is likely to be variable within a population. For example, New York City requires that some restaurants post calorie labeling as an effort to improve nutrition and decrease obesity. While health officials have reported some modest consumer behavior changes overall, no change was observed in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods (

10). Barriers to better nutrition must be understood at the population level and among groups who are most likely to have poorer-quality diets and those at highest risk for psychiatric disorders. Prevention strategies might focus on children, through targeting parents and schools as agents of change.

Future Research Directions

Rigorous research into nutritional approaches in psychiatry needs to continue to assess potential specific nutritional interventions and complex patterns of eating. It has been suggested that rather than focusing research efforts on the nutritional changes of individuals in randomized, controlled trials, research should instead focus on larger groups. Assessment and implementation of nutritional changes may need to occur "in a dynamic community setting, where many contextual factors are hardly controllable. The strict [randomized, controlled trial] design does not fit well in this context…randomizations must be done at larger unit levels such as school classes, whole schools or communities" (

11).

However, in order to assess the impact of nutritional interventions on the course of psychiatric disorders, randomized, controlled trials for individuals with psychiatric disorders or those who are at risk are needed. There is no better way to elucidate a causal relationship between nutritional interventions and psychiatric illness. Challenges include adherence to dietary patterns, a topic of great public health significance.

We need to understand what variables are associated with poorer diet quality and what factors represent modifiable barriers to improvement. There is a risk of oversimplification of dietary recommendations. Indeed, we are what we eat, literally and figuratively. Understanding eating patterns and the relationship with psychiatric disorders will likely include well beyond what we eat, to why, how, and with whom. In order for an individual to improve his or her dietary quality, one must have the prerequisite education about and comprehension of what constitutes good nutrition and also must have accessible healthy foods. Diet quality may be integrally related to social support, self-efficacy, and future-oriented perspectives. Some food intake behaviors parallel patterns of substance abuse or misuse, with cueing and reward mechanisms important to delineate.

It would be a pivotal change for psychiatry if specific dietary patterns are definitively demonstrated to prevent or diminish psychiatric disorders in prevalence or severity. However, if improving the quality of nutrition for our patients is discovered to have a modest or minimal impact on psychiatric disorders, but overall health benefits are observed, a focus on better nutrition will still represent a valuable contribution.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr. Scott A. Freeman and Ms. Elizabeth Lemon for editorial suggestions on the writing of this commentary.