Sample and Study Design

The Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology Study collected data on the prevalence, incidence, risk factors, comorbidity, and course of mental disorders in a representative random population sample of adolescents and young adults, age 14–24 years, from the general population in Munich, Germany. The baseline sample, following ethics committee approval, was randomly drawn in 1994 from the respective population registry offices of Munich and its 29 counties to mirror the distribution of individuals expected to be 14–24 years of age at the time of the baseline (T0) interview in 1995. The base population were all those born between June 1, 1970, and May 31, 1981, registered as residents in these localities and having German citizenship. These registers can be regarded as highly accurate because 1) each German is registered by his town, 2) the registers are regularly updated, 3) in the interest of scientific studies, any number of randomly drawn addresses with a given sex and age group can be obtained, and 4) strict enforcement of registration by law and the police applies. More details on the sampling, representativeness, instruments, procedures, and statistical methods of the sample have previously been presented (

21).

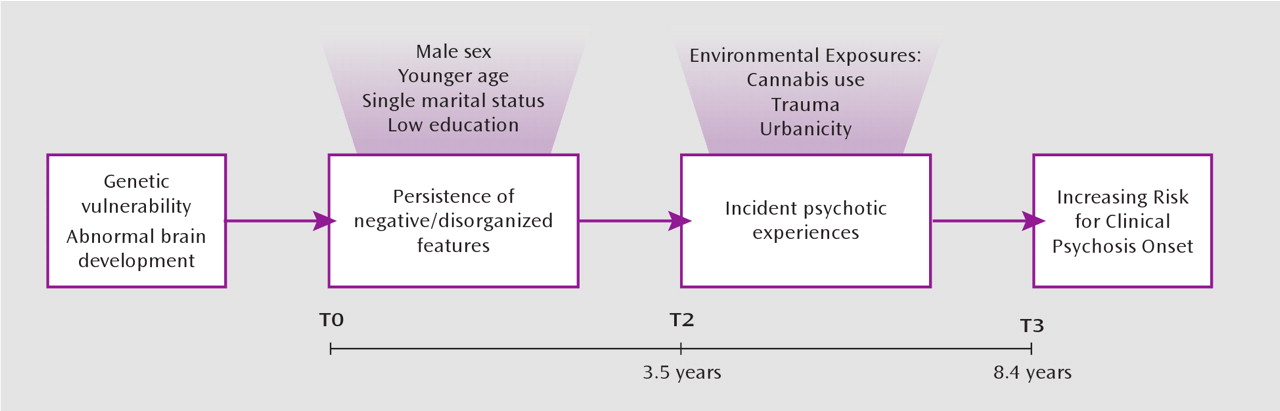

The longitudinal prospective design consisted of a baseline and three follow-up surveys (time 1, time 2, and time 3), covering a time period of on average 1.6, 3.5, and 8.4 years (range=7.3–10.5), respectively, from baseline. As the primary goal of the study was to examine developmental aspects of psychopathology, the younger group (14 and 15 years of age) was sampled at twice the rate of persons 16–21 years of age, and the oldest group (22–24 years) was sampled at half this rate. For the same reason, subjects 14–17 years of age at baseline were examined at all four time points, whereas the full baseline sample was only assessed at three time points (baseline, time 2, and time 3).

The present study is based on the three assessments that were available for the full baseline sample: 3,021 individuals 14–24 years of age at baseline and their follow-up assessments at time 2 (N=2,548; response rate=84%) and time 3 (N=2,210; 73%). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Participants were interviewed with the Munich Composite International Diagnostic Interview (

22). Trained and experienced clinical psychologists conducted the interviews at baseline (lifetime version) and follow-up assessments (interval version: covering the assessment period from the previous interview).

Psychopathology Assessment

Information from the psychosis section and the clinical interview rating section, with its embedded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (

23), were used to derive measures of psychopathological clusters. In order to calculate measures of frequency, discrete variables indicating presence or absence of clusters across interview waves were, per definition, necessary.

Negative/disorganized symptom cluster.

A combined cluster of negative and disorganized symptoms was designed, in accordance with psychopathological findings in the early course of psychosis, showing that the “Bleulerian blend” of negative, catatonic/motor, and disorganization symptoms load on a single factor, while positive symptoms load on another (

24) in agreement with Kraepelin's description in which avolition and disorganization were joined as the two defining features of the syndrome (

25). Although negative, disorganized, positive, and affective clusters consistently load on separate domains in factor analytical studies of chronic psychotic patients (

26,

27), meta-analysis indicates that negative and disorganized dimensions are conflated in their association with neurocognitive alterations, contrary to the positive and affective dimensions (

28). A sensitivity analysis was planned, reanalyzing essential results for the negative cluster and the single disorganized item separately.

At baseline and time 3, two items concerning classic negative and disorganized symptoms from the interview ratings section were used: indifference (X11) and thought incoherence or illogicality (X12). These two items were rated on a 7-point scale (1=absent, 2=very little, 3=a little, 4=moderately, 5=moderately strong, 6=a lot, 7=very much). Each item was dichotomized: absent (coded as 0) versus present (coded as 1, indicating any score above “1”). For the purpose of the analyses, presence of the negative/disorganized cluster at baseline and time 3 was defined as a rating of “present” on either of the two items.

At time 2, not only the two previous items but also five items from the interview observation section were available: flat affect (P3), slow speech (P5), slow movement (P6), poverty of speech (P7), and avolition (P8). These five items were dichotomously rated: absent (coded as 0) versus present (coded as 1). Presence of the negative/disorganized cluster at time 2 was defined as a rating of “present” on any of the seven items.

Positive symptom cluster.

Interview ratings from the psychosis section (items G1, G2a, G3–G5, G7–G13, G13b, G14, G17, G18, G20, G20C, G21, and G22a) on delusions (15 items) and hallucinations (5 items) were collected at time 2 (lifetime) and time 3 (interval version). These 20 items concern classic psychotic symptoms, including Schneiderian first-rank symptoms such as audible thoughts, thought insertion, thought withdrawal, and made acts and impulses. Participants were first invited to read a list of all the psychotic experiences and asked whether they had ever experienced such symptoms. Each psychosis item was rated absent or present. Presence of the positive cluster was defined as a rating of “present” on any of the 20 psychosis items (

6).

Depressive symptoms.

At time 2 and time 3, the 28 symptom items of the depression section were used. Items were rated either yes or no as being present for at least 2 weeks. A sum score of “depressive symptoms” was formed, with a minimum of 0 and a maximum score of 28 endorsements (

29).

Cluster persistence.

The time 2 (lifetime) and time 3 (interval) ratings for the positive cluster were used to create a three-level summary “positive cluster persistence” variable: no occurrence (coded as 0), present at one assessment (coded as 1), and present at two assessments (coded as 2). In order to have a comparable longitudinal measure of “negative/disorganized cluster persistence,” the baseline (lifetime) and time 2 (interval) measures were combined into a cumulative lifetime variable. Together with the information at time 3 (interval), this resulted in a similar three-level summary score of persistence: no occurrence (coded as 0), present at one assessment (coded as 1), and present at two assessments (coded as 2)

Other Clinical Assessments

Age, gender, social status, marital status, level of education, urbanicity, cannabis exposure, and self-reported trauma were considered.

As part of the treatment module, participants were shown a list of different types of medication and were asked to endorse those they had been given for any psychopathological or psychosomatic problem. The acknowledgment of any antipsychotic medication (item Q1EA4) reported at time 2 and time 3 was used to derive the antipsychotic treatment variable (coded as 1 for yes).

Clinical relevance of positive psychotic symptoms was assessed with interview ratings of the psychosis section (

6). Three help-seeking items assessed whether participants had ever sought help because of psychotic symptoms: seeking doctors' help because of delusions (G16) or hallucinations (G23) or seeking help from other mental health professionals, ranging from a general practitioner or school psychologist to psychiatric sheltered housing (Q1DG). A dichotomous “help-seeking” variable was created, indicating a positive answer to any of the three questions (coded as 1) versus negative answers on all.

The diagnostic interview also assesses the effect of psychotic experiences on feeling upset or unable to work, go places, or enjoy oneself at the time of having these experiences (G28); being less able to work (G29) or less able to make friends or enjoy social relationships (G29a) since these experiences began; and how much their life and everyday activities were impaired when these experiences were at their worst (G36). A dichotomous “dysfunction” variable was created representing a positive answer on any of the four questions (coded as 1) versus negative answers on all.

Finally, a dichotomous variable “psychotic impairment” was created, coded as 1 for subjects with psychotic experiences who had ratings of “1” on either help-seeking or dysfunction or both.

The interviewer's opinion regarding clinical evidence of psychological ill health (item X16) was rated according to four levels: 0=essentially not noticeable, 1=not very noticeable, 2=clearly ill, and 3=very ill. The dichotomous variable “caseness” indicated individuals with a noticeable level of psychiatric caseness (i.e., any score above “1”).

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted using the software package STATA 10.1 (StataCorp, 2008).

First, in order to investigate the reliability and the rate of the variables representing the positive and the negative/disorganized psychopathological domains, the Cronbach alpha coefficient was used as a measure of internal consistency for each symptom cluster: the negative/disorganized cluster (

24), the negative cluster (excluding the disorganized item), and the positive cluster (

6) at time 2. Alpha values of 0.7 are regarded as satisfactory. Lifetime cumulative incidence and interval prevalence estimates of the positive cluster were calculated. Prevalence estimates of the negative/disorganized cluster were calculated, with and without additional sensitivity analyses excluding 1) participants exposed to antipsychotic treatment or 2) individuals with a DSM-IV diagnosis of depression (secondary negative symptoms). The distribution of symptom clusters was examined at time 2 and time 3, distinguishing individuals with only negative/disorganized symptoms, only positive symptoms, or a combination of the two. Because additional exclusion of participants exposed to antipsychotic treatment or individuals with a DSM-IV diagnosis of depression revealed no change in the rates, no sensitivity analysis was conducted.

Second, associations between psychopathology and risk factors were examined. It was hypothesized that the negative/disorganized cluster would be associated with younger age (

30), male sex (

31), and single marital status and low educational level (

32), whereas female sex (

31), cannabis exposure (

33), urbanicity (

34), self-reported trauma (

34), and low level of education (

32) would show significant associations with the positive cluster. Logistic regression analyses were conducted with the data in the “long” format, i.e., each individual contributing two timepoint observations (time 2 and time 3). Clustering within subjects was controlled for by including a variable reflecting measurement occasion in the model. Associations were expressed as odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Third, in order to examine the natural association between the positive and negative/disorganized clusters (

24), cross-sectional associations between the two were examined, controlling for depressive symptoms. Again, logistic regression analyses were carried out with the data in the “long” format (time 2 and time 3), adjusting for the indicator variable representing measurement occasion. Given that cross-sectional associations between symptoms may arise as a function of shared interview variance or represent chronicity effects, associations between clusters were also carried out in longitudinal predictive models across measurement occasions. Thus, logistic regression was used to calculate 1) the association between the negative/disorganized cluster at time 2 and the positive cluster at time 3, controlling for depressive symptoms and excluding individuals in whom the positive cluster was present at time 2; and 2) the association between the positive cluster at time 2 and the negative/disorganized cluster at time 3, controlling for depressive symptoms and excluding individuals in whom the lifetime negative/disorganized cluster was present at time 2.

Fourth, the null hypothesis of independence of the natural courses of the two psychopathological domains (

35) was examined, analyzing the influence of the degree of persistence (from the interview assessing lifetime presence to time 3) of one psychosis cluster (i.e., positive cluster or negative/disorganized cluster) on time 3 onset of the other cluster and vice versa. To this end, logistic regression analyses were performed to examine the associations between 1) the degree of negative/disorganized persistence on the one hand and first onset (incidence) of positive cluster at time 3 on the other in individuals

without lifetime positive cluster present at time 2, and 2) the degree of negative/disorganized persistence on the one hand and positive cluster at time 3 on the other in individuals with lifetime positive cluster present at time 2 and vice versa, controlling for depressive symptoms at time 3.

Fifth, the clinical relevance of the combination of positive and negative/disorganized experiences was calculated by examining whether the association between the positive cluster and its associated psychotic impairment rating was moderated by the negative/disorganized cluster. Consistent with previous work, the interaction between the positive cluster and the negative/disorganized cluster was calculated on the additive scale (

33,

34,

36) using the STATA BINREG command, controlling for depression, with the data in the “long” format. In order to validate psychosis impairment, logistic regression analyses were conducted against the caseness and antipsychotic treatment variables.