In this issue of the

Journal, Etkin and colleagues (

1) have published a functional MRI (fMRI) study of implicit affective regulation in health and anxiety that is both provocative and exciting. Provocative because it demonstrates that the elusive process of implicit emotion regulation may be measurable, and exciting because this approach is applied to a clinical question.

The study examines the effects of trial repetition on task performance, particularly for trials with conflicting information. This work relies on more than a decade of research investigating "the conflict monitoring theory" (

2). This theory posits that the resolution of a conflict—defined as the concomitant presence of stimuli calling for incompatible responses—requires initial

detection of the conflict as well as its subsequent

resolution. The

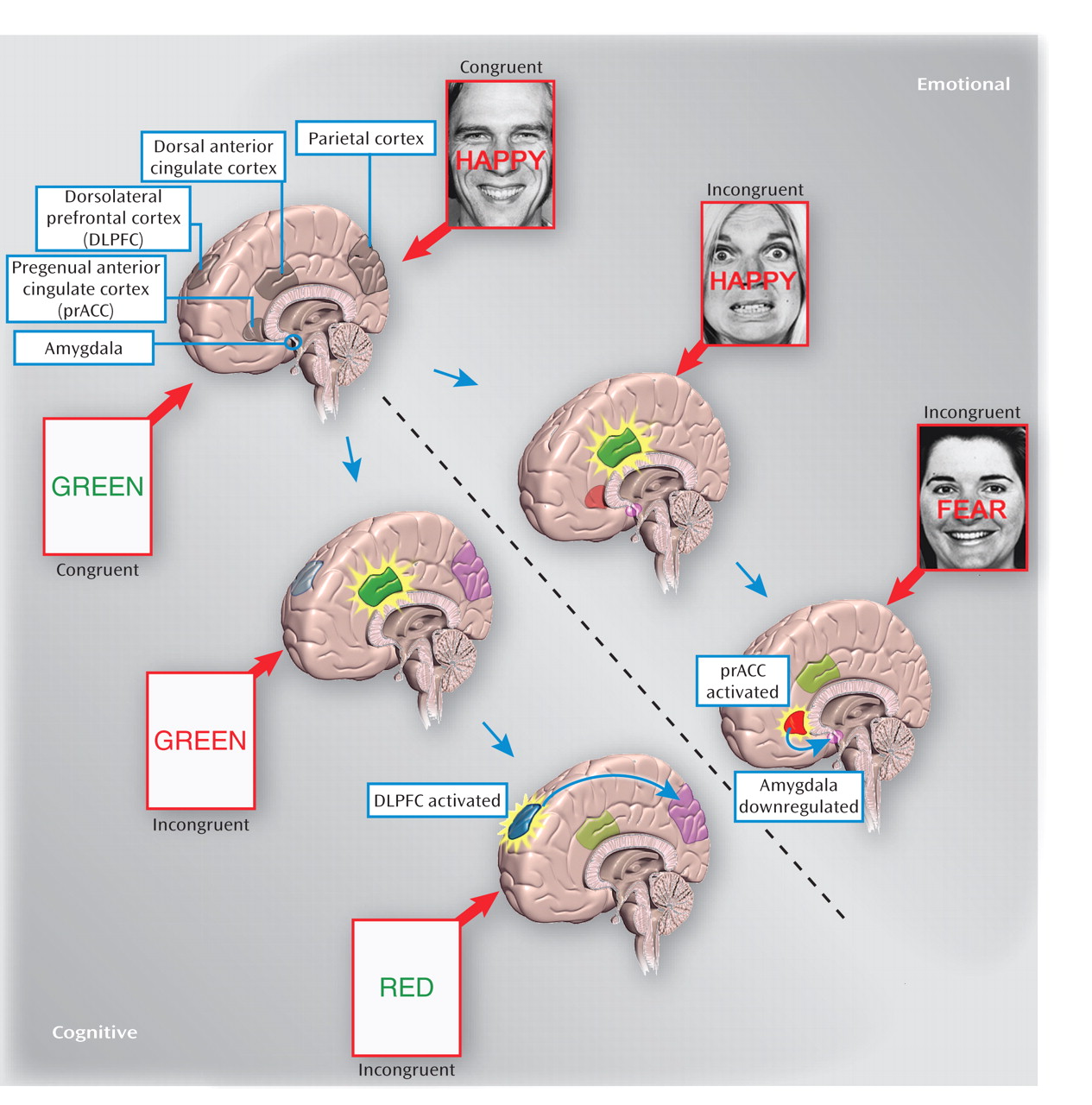

detection site resides in medial prefrontal structures, including the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex extending dorsally to premotor regions. Once activated, the detection system alerts a cognitive control system that initiates conflict resolution by modulating information processing, i.e., facilitating the processing of the appropriate response while hampering the processing of the incorrect, conflictual, response. The

resolution site resides in regions of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. The modulated information-processing streams lay in posterior brain regions (e.g., the parietal cortex), which are dedicated to sensory-perceptual integration. The study by Etkin and colleagues draws on the critical observation that performance in a conflict trial is influenced by the level of conflict present in the preceding trial. Specifically, performance on a conflict trial is facilitated when preceded by a similar conflict trial. This effect, which relies upon small behavioral adjustments, has been called

conflict adaptation (

3).

The paradigm used by Etkin and colleagues employs pairs of stimuli that combine fearful or happy faces with the words "FEAR" or "HAPPY." In this study, "conflict" entails the presence of competing stimuli (e.g., "HAPPY" printed on a fearful face) in incongruent trials, and "absence of conflict" refers to synergistic stimuli (e.g., "HAPPY" on happy faces) in congruent trials. Subjects were instructed to identify the facial emotion (target stimulus) as fast as possible, while ignoring the word (distracter stimulus). Consistent with the conflict monitoring theory described above, the incongruent stimuli engage the conflict

detection node. This node, in turn, activates the conflict

resolution system, which biases information processing and promotes correct responding. It is at this critical point that the focus of this study lies. The idea is that the conflict

resolution node, by remaining active, would facilitate response to a subsequent incongruent stimuli trial; that is, facilitation of the response to an incongruent trial when preceded by an incongruent trial. This facilitation, termed "conflict adaptation" is implicit, because individuals are not aware of it. Notably, the effect can be captured by a speeded reaction time and is reflected at the neural level by activation of a prefrontal region that initiates conflict resolution (

2).

As described above, Etkin and colleagues use emotional stimuli, in contrast to the classic studies that employed nonemotional stimuli (such as the color Stroop task in which subjects have to identify the actual color of a word when the word itself reads a different color, i.e., answering "green" when the word "red" is printed in green-colored type [

2,

5]). Doing so, Etkin and colleagues extend previous, purely cognitive work into the domain of affective neuroscience. In this context of emotional stimuli, conflict adaptation recruits the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex instead of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (

Figure 1). This pregenual anterior cingulate cortex activation presumably down-regulates amygdala function, as inferred by the negative functional connectivity found between these two regions in healthy individuals. Notably, the conflict resolution node differs in the context of emotional stimuli (pregenual anterior cingulate cortex) versus nonemotional stimuli (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) (

4). Of particular importance is the novel finding that patients with generalized anxiety disorder exhibit an absence of conflict adaptation; these individuals did not exhibit speeded reaction time or recruitment of the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex. The research and clinical implications of this finding are impressive.

With this study, Etkin and colleagues provide a research tool to measure regulation of emotional information that does not depend on self-reports and is sensitive to psychopathology. Furthermore, these findings support existing theories of emotion regulation that implicate the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex (

6). Most of this earlier research has used strategies that instruct study participants to modulate emotional responses (e.g., reappraisal or redirected attention) and that rely on explicit manipulations. In contrast, Etkin and colleagues examine implicit, automatic regulation. Related to this fundamental difference, previous investigations focused on experienced emotion, whereas the present study examines cognitive response (selective attention) to conflict between emotional stimuli. In other words, whereas prior work examined "emotion regulation" per se, Etkin and colleagues probe "conflict regulation" and, by using emotional stimuli, challenge neural circuits of emotion appraisal. Whether and how such automatic emotion-related responses contribute to daily emotional experiences remain unknown. However, the finding that individuals with generalized anxiety disorder are impaired on this function suggests that this deficit may contribute to affective dysregulation. In the same vein, the possibility that patients with generalized anxiety disorder could also be impaired on a purely cognitive conflict adaptation paradigm might mitigate the specific relevance of the present findings to emotion processing. Nevertheless, this would not diminish the potential treatment implications. Indeed, the "conflict adaptation" deficit might very well explain the inability of generalized anxiety disorder patients to dampen feelings of anxiety. As a result, strengthening the underlying neural network of "conflict adaptation" via relevant behavioral training could remedy this deficit (similar to the novel Attention Bias Modification Treatment developed for other anxiety disorders [

7]).

Finally, the premise of this study does raise one important caveat. The claim that the task probes "emotion regulation" rests on the emotional nature of the stimuli and the neural responses involved (e.g., pregenual anterior cingulate cortex is typically recruited in affective processes, whereas the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is recruited in studies of cognitive conflict adaptation [

2]). However, no evidence exists that the conflict adaptation effect exhibited in the present study modulates emotional experience. This type of inferences from specific patterns of neural activation to behavior is common in the interpretation of neuroimaging studies. Because they can alternately foster novel theories or stimulate invalid lines of research, such inferences can have tremendous consequences.

Despite this caveat, the study by Etkin and colleagues in this issue of the Journal has the potential to ignite a novel, influential, and highly promising line of research that ingeniously applies a well-described purely cognitive phenomenon to mechanisms pertaining to emotion processing. This line of research will be particularly relevant to automatic mechanisms underlying biased processing of affectively laden stimuli that contribute to anxiety disorders. The study provides insights that may eventually translate into innovative therapies for anxiety disorders.