Anhedonia has long been considered a core clinical feature of schizophrenia (

1–

3). The most common understanding of anhedonia is that it reflects a diminished experience of pleasure. Although this definition clearly applies to individuals with major depression who report experiencing less pleasure when exposed to activities or stimuli that were previously enjoyable and who rate positive stimuli as being less pleasant than do healthy comparison subjects (

4–

7), it is uncertain whether these notions accurately reflect anhedonia as it occurs in schizophrenia.

Confusion regarding the nature of anhedonia in schizophrenia comes from a consistent set of contradictory findings in the empirical literature, which have come to be termed the “emotion paradox.” Patients report levels of positive emotion similar to those of healthy comparison subjects when providing reports of current feelings, but they report less pleasure relative to comparison subjects when reporting their noncurrent feelings (see references

8,

9 for a meta-analysis and review). When results from these diverse methods are viewed together, it is unclear what anhedonia actually reflects in schizophrenia. In this article, we review the empirical literature on anhedonia and emotional experience in schizophrenia through the lens of a well-validated model of emotional self-report developed in the affective science literature (

10) and use this model to resolve the “emotion paradox” and provide a new conceptualization of anhedonia.

Is There an “Emotion Paradox” in Schizophrenia?

In clinical practice, it is often assumed that the same processes are involved in all types of emotional self-report; however, this assumption is mistaken. There is consistent empirical evidence for discrepancies among different types of emotional self-report indicating that healthy individuals frequently report differences in what they are currently experiencing compared with what they have experienced in the past or expect to experience in the future (

10,

30,

31). These discrepancies result from accessing different types of knowledge when providing the various types of emotional self-report. Each source of information can result in a different pattern of self-reported emotional experience, depending on what is required by the method of measurement, and inconsistencies among the different methods of assessment would thus be expected.

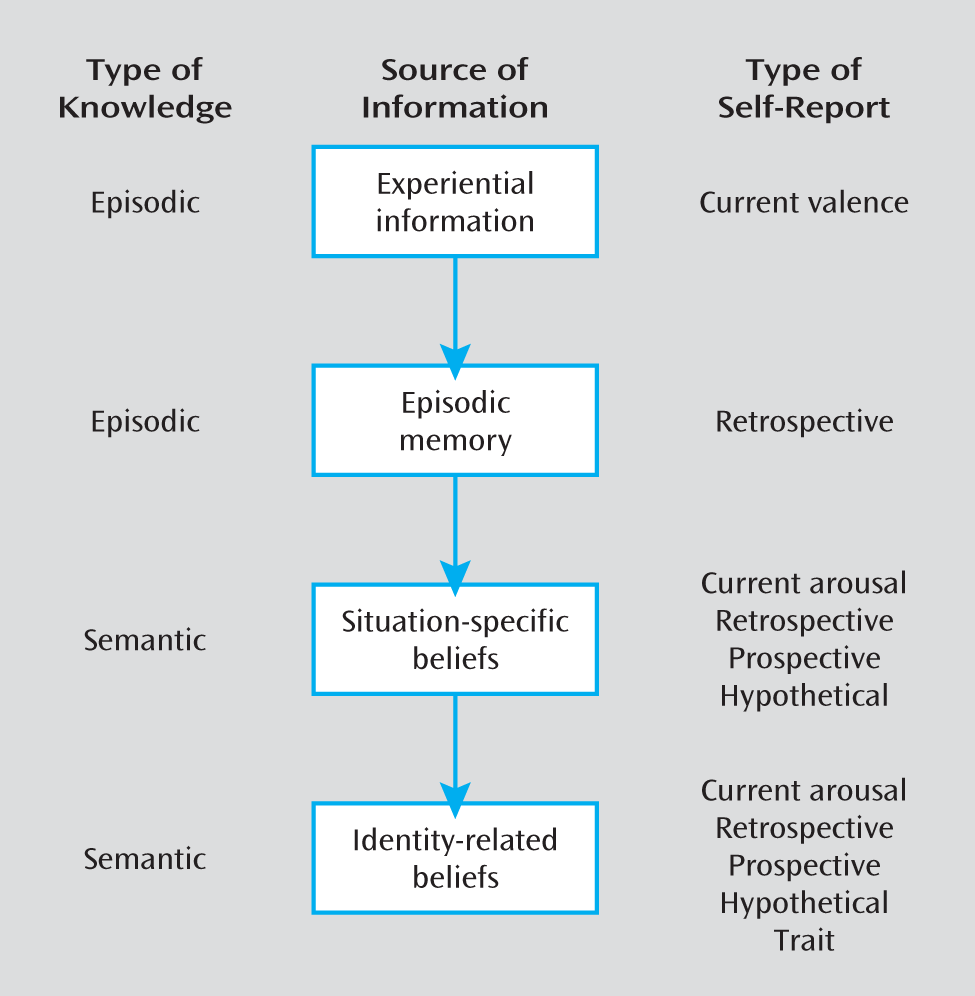

The accessibility model of emotional self-report, a model of emotional self-report developed in the affective science literature by Robinson and Clore (

10), clarifies why such discrepancies are likely to occur and delineates the sources of knowledge that people access when providing reports of current and noncurrent feelings. The model proposes that people may access four sources of information when reporting their feelings: 1) experiential knowledge, 2) episodic memory, 3) situation-specific beliefs, and 4) identity-related beliefs. Individuals are thought to prioritize these sources of information, relying first on the most specific and accessible source of information that is relevant to the query presented. In this sense, when a given query renders one type of knowledge inaccessible, people respond by accessing the next most specific source of information that is available (

Figure 1).

In brief, Robinson and Clore (

10) propose that when reporting on current feelings, individuals access experiential knowledge and report directly on their emotions in a way that is uninfluenced by episodic memory abilities or overarching attitudes and beliefs. However, when required to provide self-report of noncurrent feelings, individuals attempt to utilize episodic memory to retrieve relevant contextual details that can enable them to re-create their previous emotional experiences (

Figure 2). To the extent to which enough contextual details can be retrieved to generate an emotional experience similar to the one at the time of the initial episode, individuals are able to use episodic memory to report their recent emotions, and these reports are consistent with their previous experiences. However, when episodic memories are inaccessible or are irrelevant to the response format at hand, people will rely on broader sources of information that are available to them, namely, situation-specific or identity-related beliefs. These most general sources of knowledge include beliefs about which types of emotions are likely to be elicited by specific situations (e.g., “Social interactions are enjoyable”), as well as general attitudes and beliefs that the person holds about him- or herself (“I am generally a happy person”), respectively.

Consistent with this model, there is evidence indicating that reports of current and noncurrent feelings of positive emotion made by healthy individuals diverge in meaningful and expected ways. For example, when healthy individuals are asked to rate their prospective pleasure before a vacation, their in-the-moment pleasure during a vacation, and their retrospective pleasure after a vacation, they typically overestimate their level of pleasure prospectively and retrospectively relative to what they experienced in the moment (

32). Robinson and Clore (

10) propose that this bias toward overestimating positive emotions during reports of noncurrent feelings occurs because healthy individuals draw on semantic knowledge stores and rely on situation-specific or identity-related beliefs when making these reports. Elevated reports of noncurrent relative to current feelings therefore reflect that most healthy individuals believe that they are generally in a moderately positive mood and that specific types of situations (e.g., vacations) are pleasurable.

Much like healthy individuals, individuals with schizophrenia also show discrepancies among reports of current and noncurrent feelings (as previously reviewed). Below we report a secondary analysis of data from Heerey and Gold (

33) and Strauss et al. (

29) to examine whether schizophrenia patients and healthy comparison subjects display the same patterns of relationships between reports of current and noncurrent feelings.

To test the hypothesis that patients and comparison subjects display similar patterns of emotional self-report, we first examined whether various reports of noncurrent feelings were more highly correlated with each other than with reports of current feelings. Measures of current feelings (see reference

33) consisted of self-reported feelings of positive and negative emotion in response to pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral stimuli from the International Affective Picture System (

34). Reports of noncurrent feelings were examined from all of the major emotional self-report response formats, including retrospective (the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms), hypothetical (the Chapman Physical and Social Anhedonia Scales and the Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale), trait (the Positive and Negative Affect Scale) (

35), and prospective (the anticipatory pleasure subscale of the Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale) measures. As can be seen in

Table 1, for both comparison subjects and patients, in-the-moment valence reports (i.e., reports of current feelings) were not significantly correlated with trait positive and negative affect on the Positive and Negative Affect Scale or the Chapman Physical or Social Anhedonia Scales (i.e., reports of noncurrent feelings). Additionally, there was no significant association in patients between valence reports and anhedonia on the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms.

Table 2 presents correlations among various self-reports of noncurrent feelings in comparison subjects and patients; both groups generally show moderate relationships among the trait, hypothetical, and prospective reports. Importantly, in both groups, the magnitude of correlations among the various reports on noncurrent feelings is higher than the magnitude of correlation between reports on current and noncurrent feelings.

A number of studies of healthy individuals indicate that reports of current and noncurrent feelings are often moderately correlated with each other (e.g., references

36,

37; see reference

10 for a review) but that various measures of noncurrent feelings tend to correlate with each other more highly than they do with measures of current feelings. This pattern of correlations is consistent with Robinson and Clore's (

10) notion that current and noncurrent emotion reports are completed by accessing different sources of emotion knowledge. Relatively few studies have reported correlations among a wide number of emotional self-reports in schizophrenia; however, there is consistent evidence that patients display a pattern of correlations among reports of current and noncurrent feelings that is similar to that displayed in healthy comparison subjects (

13,

15,

38,

39).

Although additional studies are needed to make a definitive determination, these findings suggest that there is in fact no “emotion paradox” in schizophrenia—at least not in the sense that different types of emotional self-report lead to inconsistent results in patients but not healthy subjects. However, this should not be surprising and should even be expected, because it is known that individuals complete reports of current and noncurrent feelings by accessing different sources of emotion knowledge (

10). What is surprising, however, is that patients and healthy comparison subjects show different patterns of self-report across measures of current and noncurrent feelings. Whereas healthy subjects report higher levels of noncurrent than current positive emotions, individuals with schizophrenia do not. This pattern of self-report may be a reflection of patients

underestimating their positive emotions prospectively and retrospectively or of patients having a reduced or absent

overestimation bias. We are unaware of any sampling studies asking patients and comparison subjects to provide prospective, current, and retrospective self-reports using the same reporting format; such a study would clarify which interpretation is correct.

What Do Diminished Reports of Noncurrent Positive Emotion Reflect in Schizophrenia?

When viewed in relation to the Robinson and Clore model (

10), the apparent discrepancies among different types of self-report are clearly interpretable. When asked to make reports of current positive emotion, patients, like comparison subjects, will access experiential knowledge and report directly on their feelings. In this sense, reports of current feelings are the only true indication of a person's “capacity” for pleasure when exposed to a pleasurable event or stimulus because he or she relies only on experiential emotion knowledge. The fact that patients and comparison subjects report experiencing similar levels of pleasure when providing reports of current feelings suggests that the long-held notion that people with schizophrenia have a reduced “capacity” for pleasure (

3) should no longer be viewed as an accurate conceptualization of anhedonia as it occurs in this patient population (see also references

8,

9,

13,

15,

33).

The reports of low levels of positive emotion that have been taken as an indication of anhedonia occur when patients are asked to report their noncurrent feelings using retrospective, hypothetical, trait, and prospective formats. What these self-reports have in common is that they require access to semantic rather than experiential emotion knowledge and thus require that subjects access beliefs about pleasure. For example, measures with hypothetical reports like the Chapman scales are by their nature completed by accessing semantic memory, and people respond to individual items by drawing on situation-specific or identity-related beliefs. Similarly, the “in general” time frame in trait reports makes it difficult to average across life events, and trait measures are completed by accessing beliefs about pleasure. The reports of lower levels of positive emotion observed using the various reports of noncurrent feelings can thus be interpreted as reflecting that patients do not display the same retrospective/prospective overestimation bias as comparison subjects and that they either do not possess normative beliefs regarding whether specific situations result in pleasure or do not hold the same broad identity-related beliefs as comparison subjects. Future studies should investigate whether the self-reports of low levels of noncurrent positive emotion seen in schizophrenia reflect situation-specific, identity-related, or both types of beliefs.

It is of considerable clinical importance to understand the meaning of retrospective reports of pleasure that are obtained during a symptom interview. When providing retrospective reports, individuals attempt to retrieve contextual details of episodes that occurred in the time period that is queried (e.g., the past 2 weeks, the past month) and reconstruct their past feelings by recalling relevant event-related details and past thoughts (

10,

30,

31). The ability to recall these contextual details fades quickly over time (

40), and when there are too few episodic details to facilitate reports about past emotions, individuals access semantic memory and rely on more general beliefs about their emotions to fill in the details of what they cannot remember (

31). In such cases, retrospective reports may be inconsistent with the actual emotions experienced during the period in question. The wider the time frame used in the query, the more likely a subject will be to rely on semantic rather than episodic memory to complete the emotion report. In healthy individuals, there is evidence that episodic memory can typically be accessed to complete emotion reports for time frames narrower than “the last few weeks” and that semantic memory is accessed for time frames broader than this (

31).

These findings are important for understanding the meaning of retrospective emotion reports in schizophrenia and what appear to be contradictory findings in the empirical literature. On the one hand, we have experimental data from studies showing that patients do not differ from comparison subjects in retrospective pleasure reports when relatively short time frames (e.g., 4 hours) are used (

13,

38), and on the other hand, we have clinical interview data collected using wider time frames (e.g., past 2 weeks) in which patients retrospectively report diminished pleasure (

25). A likely explanation for these discrepancies is that when patients are asked to provide retrospective reports over shorter time frames, they can rely on episodic memory and accurately recall their initial experience of positive emotion. However, when providing retrospective reports over longer time frames, patients (much like comparison subjects) are likely to rely on semantic memory because they cannot recall enough contextual details of episodes that occurred during these wider time frames. Retrospective reports of low levels of positive emotion in the context of longer time frames therefore likely reflect that patients base their report on their general sense of well-being, rather than the actual emotions they experienced during the time frame in question. The severity of patients' episodic memory impairments should dictate the point at which they no longer base their report on episodic memory and shift to relying on semantic memory. This should be taken into account when conducting symptom interviews; the time frame selected for the retrospective report is of critical importance because it dictates whether the self-report reflects memory for recent feelings, as intended, or beliefs about how the patient thinks he or she generally feels, which may be inaccurate.

Newer, “next-generation” negative symptom scales include prospective emotion reports for assessing anhedonia (

41,

42). Prospective reports are less influenced by episodic memory than other types of emotion report and more influenced by beliefs about emotion (

10). Studies utilizing prospective self-reports that have found patients to report less predicted future pleasure than comparison subjects (

19) provide converging evidence with studies utilizing retrospective, hypothetical, and trait self-report formats and indicate that patients have abnormal beliefs related to pleasure and lack the overestimation bias seen in comparison subjects. Overestimating future pleasure occurs for a number of reasons, including accessing unrepresentative memories to gauge how good one will feel in the future; focusing on essential features of future events, particularly far-off events, and ignoring inessential features that may be less pleasant and lower the overall net value of the event; focusing on early moments of a future event and ignoring that later feelings are likely to be less intense; and ignoring the fact that contextual factors that are present or not present at the moment may be more or less important in the future (

43). Any number of these factors may function differently in schizophrenia and make prospective overestimation less likely.

It will be important to determine how patients develop these beliefs of low pleasure. We speculate that such beliefs may stem from not having an adequate number and diversity of pleasurable experiences to develop normative beliefs of pleasure, as well as early negative life events (e.g., social rejection) that shaped their identity-related and situation-specific beliefs about pleasure.

Role of Cognitive Impairments in Emotional Self-Report in Schizophrenia

It is clear that there are different cognitive demands associated with various emotional self-reports, and these demands may affect patients and healthy subjects differentially, depending on the nature and severity of patients' cognitive impairments. In addition to the influence of episodic memory deficits on retrospective reports previously discussed, hypothetical reports are also likely to be influenced by cognitive impairments. Hypothetical reports like the Chapman scales require that individuals form a mental representation of the situation being probed (

44)—a process that requires working memory. It is likely that the severity of patients' working memory impairment would interact with their ability to complete hypothetical reports, potentially causing them to rely on broad identity-related beliefs when they have difficulty forming a mental representation of the hypothetical scenario. Thus, the presence of cognitive impairments may influence patients' reports of noncurrent feelings in a predictable way, causing them to access semantic memory and base their self-report on broad identity-related beliefs instead of the intended sources of emotion knowledge (i.e., episodic memory for retrospective reports and situation-specific beliefs for hypothetical reports).

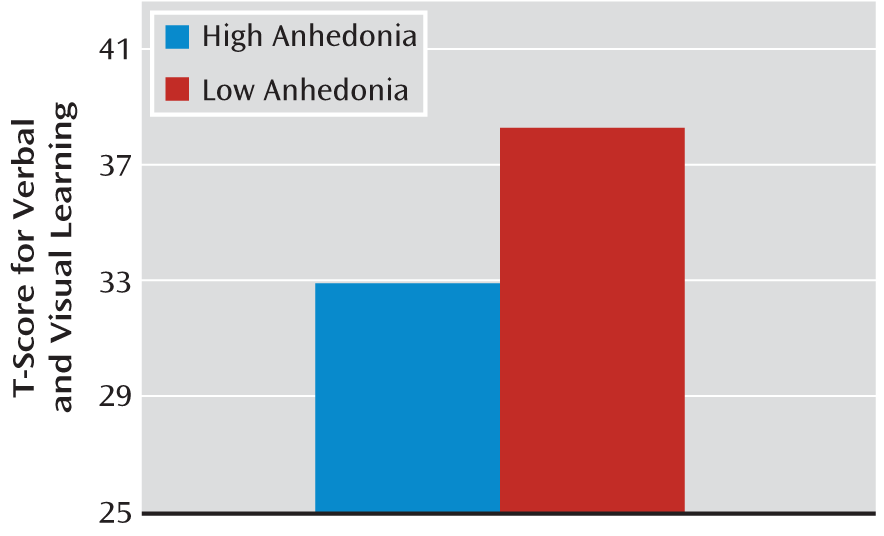

To test the possibility that cognitive processes are related to reports of noncurrent but not current emotion in schizophrenia, we conducted a secondary analysis of data from Heerey and Gold (

33) and Strauss et al. (

29). We hypothesized that 1) retrospective reports of pleasure on the anhedonia item of the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms would be related to poorer episodic memory on a standard neuropsychological memory measure, and 2) reports of pleasure on hypothetical scales like the Chapman scales and the Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale would be related to working memory impairments. As can be seen in

Table 1, reports of current feelings in response to positive stimuli were not significantly correlated with either working memory or episodic memory. This nonsignificant correlation is consistent with Robinson and Clore's (

10) notion that cognitive processes do not affect reports of current feelings. As hypothesized, retrospective reports of pleasure on the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms were associated with poorer episodic memory (

Table 2), and patients with mild to severe clinically rated anhedonia had poorer memory than patients with questionable or no anhedonia (

Figure 3). Also as predicted, poorer working memory was significantly correlated with reports of lower levels of pleasure on hypothetical reports, as indicated by significant associations between working memory performance and anhedonia on the Chapman scales and lower levels of pleasure on the consummatory subscale of the Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale (

Table 2). Notably, the correlation between working memory and the anticipatory subscale of the Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale was nonsignificant; however, this may reflect the lack of an anticipatory pleasure deficit in our patient sample (

29).

Overall, these findings provide some preliminary support for the notion that cognitive impairment is related to reports of noncurrent feelings in schizophrenia. Other studies have also demonstrated the role of cognitive and neurophysiological impairments in emotional self-report. For example, Ursu and colleagues (

45) found that patients displayed neural activation similar to that of healthy subjects in the presence of emotional stimuli at prefrontal, limbic, and paralimbic structures but reduced activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during a 12.5-second delay period that occurred before subjects made a retrospective emotion report, when cognitive control processes were actively engaged in maintaining emotional experience. Burbridge and Barch (

46) found that working memory moderates the relationship between hypothetical reports and in-the-moment pleasure reports, which is consistent with the notion that working memory deficits may predict the extent to which patients complete noncurrent feeling reports by relying on semantic rather than episodic emotion knowledge.

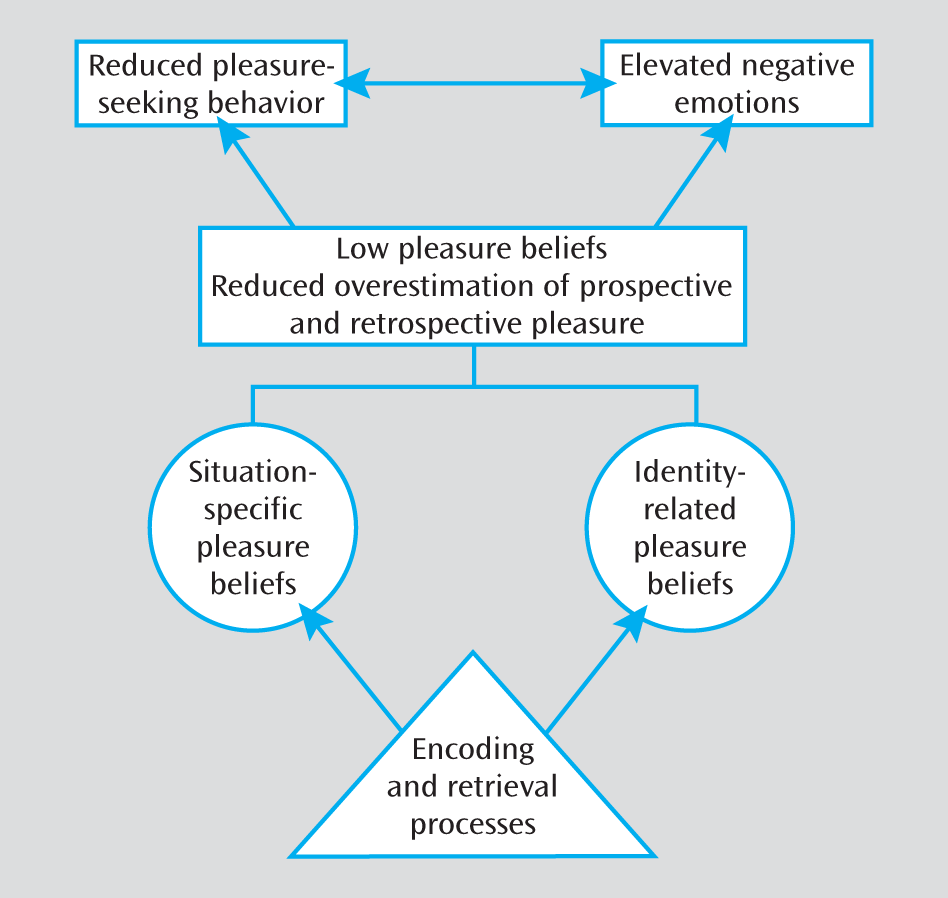

An important question also remains as to how patients maintain beliefs of low pleasure despite having some life experiences in which they do engage in pleasure-seeking behavior and experience high levels of positive emotion while doing so. Why do these experiences not serve as counterevidence to alter these beliefs? One possibility is that cognitive processes facilitate the maintenance of such beliefs. In the literature on personality and autobiographical memory in healthy individuals, there is evidence that broad identity-related beliefs are sometimes dissociated from daily life events (

47). This research demonstrates that individuals form emotional schemas (e.g., “How I generally feel during family interactions”) and that these schemas are used to organize and reconstruct details from life events, especially those occurring further in the past. When a life event does not match the schema that an individual holds, it is often forgotten or not retrieved (

47,

48). These schemas thus play a major role in forming and maintaining identity-related beliefs, even in the face of contradictory evidence. Once such beliefs are formed, they are often slow to change in response to actual experiences because individuals encode and retrieve information consistent with their beliefs, instead of information that contradicts them, to maintain a consistent self-representation (

48). It is possible that schizophrenia patients maintain the belief that they do not experience pleasure despite counterevidence from real-world experiences because everyday experiences of pleasure are inconsistent with their long-held beliefs and thus are not encoded or retrieved. Studies of emotional memory in schizophrenia are consistent with this notion, providing evidence for aberrant encoding and retrieval of positive stimuli (

49).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Robert W. Buchanan, William T. Carpenter, Alex S. Cohen, Bernard A. Fischer, Laura D. James, William R. Keller, Jeff T. Larsen, Katiah Llerena, and Nicholas Thaler for their helpful comments on drafts of the manuscript. They also thank the subjects who participated in the studies and the staff at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, who made completion of the study possible. They are especially thankful to the members of Dr. Gold's laboratory, Erin Heerey, Jackie Kiwanuka, Sharon August, Zuzana Kasanova, Leeka Hubzin, and Tatyana Matveeva, who conducted participant recruitment and testing.