“Ms. X” was a 29-year-old married woman living with her teenage daughter and her parents-in-law in a farming village of 700 in central China while her husband worked in a coastal city. For many years, Ms. X had experienced her in-laws as contemptuous and resentful because she had not produced a son for the family. Increasingly, she had been struggling with feelings of powerlessness and worthlessness. She lamented that she would be “better off dead.” She never openly expressed sadness, but she felt guilty for her thoughts. She stopped socializing. She blamed her husband for not standing up for her. The home was usually coldly silent; her daughter spent most of her time with friends. The village, including the local physician, was also talking about her strange changes. One day, Ms. X unexpectedly cried out loud at the store over some critical comments about her daughter being neglected. Feeling ashamed and angry, she drank some pesticide stored in her backyard, yelling to her mother-in-law, “I will show you what happens when your family treats me so badly!” She was rushed to a regional hospital; the local physician's referral note said, “Domestic conflict and impulsive behavior problems.”

In China, very little psychiatry is taught in the 3-year medical school program that provides the vast majority of China's 650,000 rural physicians with their training (

1–

3). Previously known as Chairman Mao's “barefoot doctors,” rural physicians are the front-line medical professionals for 60%–70% of China's 1.3 billion rural dwellers (

4). However, psychiatry remains a relatively foreign subject, and rural physicians are not expected to treat psychiatric disorders and are not officially allowed to prescribe psychotropic medications.

Since their inception in 1965, the “barefoot doctors” have dramatically improved rural emergency care, immunization rates, infectious disease control, and infant and maternal mortality rates; life expectancies in China nearly doubled between 1949 and 1993 (

5,

6). These physicians were officially renamed as “rural physicians” in 1985, and their training has been standardized in the 3-year medical school program (

6). However, psychiatry is not a core part of their education (

7,

8). This limitation is due not only to resource shortages but also to the long-held perception that psychiatry is an alien import, practiced only in urban centers. Up to the 1980s, psychiatry was politically denigrated as bourgeois, and its practice was limited to treating psychotic illnesses and, as some critics reported, to social control (

3,

9).

Recent research has shown that China's 1-month prevalence rate of any mental illness is 17.1%, which is comparable to developed world figures. Rural rates are higher than their urban counterparts, with high rates of depression and anxiety disorders. Only 8% of all sufferers ever seek professional help, with even lower rates for rural sufferers (

10). World Health Organization research has also shown that neuropsychiatric conditions and suicide combined account for more than 20% of the total burden of illness in China (

11). Although some preliminary data suggest decreasing suicide rates, the most recent large-scale studies show that the overall suicide rate in China is roughly 20 per 100,000—about two times the global average—and 93% of all suicides in China occur in rural areas (

10–

12). In addition, a widening urban-rural socioeconomic gap and abolishment of the public rural health insurance in the 1980s and 1990s have led to erosion of rural health care. Social issues such as increasing divorce rates, migration of workers, and substance abuse are on the rise, and as a result, mental health problems are increasing as well (

10,

13). Rural physicians in China are woefully unprepared to address these challenges.

In the United States, primary care has been recognized as the “de facto” mental health system, particularly in rural areas (

14). With appropriate training and support, Chinese rural physicians could make an enormous contribution to front-line psychiatric care (

15). Education in psychiatry is both timely and necessary. We report here on one effort to introduce psychiatric education for 11,000 rural physicians in 10 provinces of China, potentially affecting millions of rural inhabitants.

Background

The Rural Psychiatry Training Initiative was part of the Wennuan (“Warmth”) Project, funded by a philanthropic Foundation (Li Jia Jie; total project budget, US$4.3 million) and supported by the Chinese Ministry of Health. The project aimed to “improve medical training” for “10,000 rural physicians,” with free training in internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, gynecology, and emergency medicine. Psychiatry was the only mandatory topic for all trainees. From 2007 to 2009, the project was conducted in 10 provinces at 119 training sites (for example, Inner Mongolia [12 sites], Jiangxi [11 sites], Hunan [11 sites], Sichuan [21 sites]).

Trainee Background and Practice Settings

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of samples of trainees in two provinces. All trainees reported little or no prior exposure to psychiatry (some had 4 to 12 hours of lectures on psychiatry under neurology or internal medicine, but none had clerkship training). The rural physician is typically a key member of the village (population range, 200–1,500); the majority work as farmers as well. Rural physicians do not typically screen for or treat mental disorders, nor do patients seek psychiatric help from them. Because of stigma, lack of awareness, and lack of resources, people usually try to manage psychiatric problems for as long as possible within the family; when crisis is reached, patients are sent to regional hospitals. There are no services such as counseling or psychosocial support. Physicians typically restrict their role to that of detached medical expert in therapeutic relationships. Asking the types of personal questions required in taking a psychiatric history is often experienced as intrusive and lacking in boundary maintenance, especially in a small village. Most rural physicians avoid psychiatry for these reasons, and most patients believe that mental illnesses are caused by bad luck, ill fate, family factors, and a lack of self-discipline (

10).

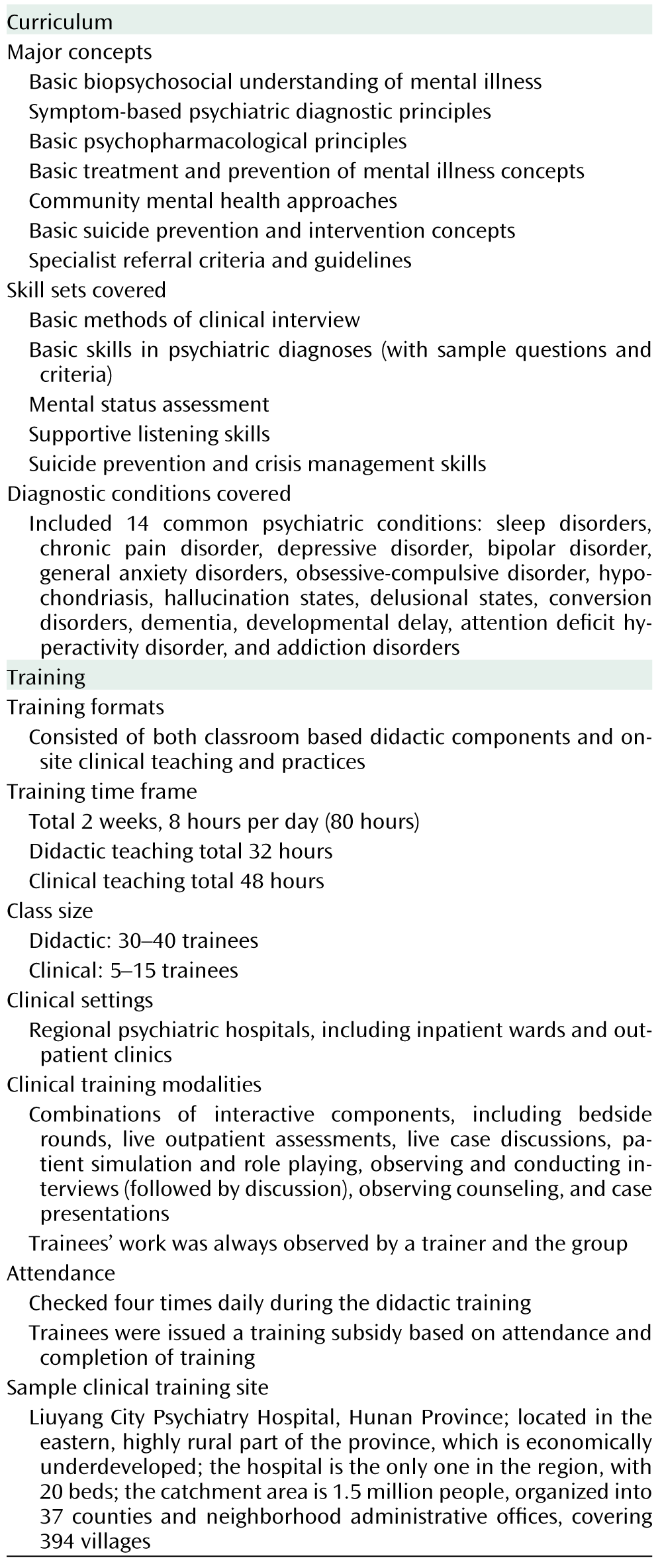

The Curriculum, Training Format, and Trainers

The curriculum committee consisted of psychiatrists with experience in rural practice and education who designed the textbook and teaching plans specifically for rural physicians according to their training background. The curriculum included basic knowledge and skills training, with coverage of 14 common psychiatric conditions and a special focus on suicide risk assessment and management skills. How to reach and refer to specialists was also emphasized to ensure that trainees felt supported. Trainees spent twice as much time in clerkship-style clinical training as in classroom sessions. Trainees were given moderate financial subsidies for attendance. Overall trainee attendance was 95% in Jiangxi and 88% in Hunan. The trainers, who were psychiatrists from regional hospitals or organizing universities, received a 2-day training course and passed a psychiatric knowledge test.

Figure 1 summarizes the curriculum and training.

Outcome Evaluation and Response to the Training

We used a “biopsy” approach in our evaluation by sampling trainees and trainers from two representative training sites: Jiangxi in southeast China (N=1,100) and Hunan in south central China (N=1,000). We performed quality improvement-related evaluations in three stages: before training, immediately after training, and 6 months after training. We also held an international forum 1 year after the initiative to discuss its outcome and longer-term impact.

Pretraining Evaluation

A questionnaire was designed to assess trainees' attitudes toward psychiatry. Surveys of randomly selected samples of trainees from Jiangxi (N=110) and Hunan (N=110) found that trainees' opinions of psychiatry were in general mixed, and relatively low overall. The vast majority acknowledged that they had “no prior experience” in learning psychiatry. Roughly 40% reported negative attitudes: mental health training “would not be helpful”; it was “not necessary” to conduct this training; it was “not rural physicians' role” to treat mental illness. Moreover, some thought psychiatry was “mysterious,” “useless,” “not scientific,” and “can be harmful.” Some feared that they would end up doing more work that they were not equipped for or felt uncomfortable performing; that backup resources were too limited; and that psychiatry would constitute a new “burden.” Many mentioned stigma as a significant issue and barrier. About 30% of the responses showed some curiosity, and another 30% showed a more positive attitude about learning psychiatry.

Posttraining Evaluation

Written examination.

The examination included short answers, fill-in-the-blank items, and multiple-choice questions to assess both psychiatric knowledge and clinical diagnostic skills. Randomly sampled trainees from Jiangxi (N=36) and Hunan (N=21) were tested. The average score was 83.5% for the Jiangxi sample (range, 71%–92%) and 84.7% for the Hunan sample (range, 76%–92%).

Semistructured questionnaire and group discussion.

Randomly selected trainees from Jiangxi (N=31) and Hunan (N=53) participated in these qualitative assessments. The questionnaire and discussion were aimed at learning about trainees' reactions and attitude changes and obtaining feedback about the training. This component included a 3-point scale (poor, average, or good) to assess general satisfaction; 80.6% of the Jiangxi sample and 90.6% of the Hunan sample found the training “good,” and the remainder rated the training as “average.”

We performed a content analysis on the open-ended questionnaire answers and group discussion notes by extracting key points and coding and categorizing them. Several themes emerged. The majority found the “first time ever” novelty of learning psychiatry very interesting or exciting. Some reported a positive, more “formal concept” of psychiatry and now thought of psychiatry as less “strange” or “mysterious.” Many especially liked the clinical, experiential learning over traditional classroom teaching. Many were surprised by the utility of psychiatry, as they did not anticipate that it would be useful or worthwhile, and the training changed their minds. More than 90% reported having learned “new skills” and being “more confident” in dealing with mentally ill patients; about 75% felt that the content would be useful in their medical practices. Many trainees reported recognition of stigma and that the training had “changed the way” they saw mental illness and “broadened” their views about patients' experience and that they would “not be as impatient and resentful” or “judgmental” of patients with mental disorders. Some said that knowing how to differentiate psychosomatization from “real” mental illness can help to lower stigmatization.

Almost all trainees showed an interest in further training; specifically, they were interested in developing skills in psychiatric symptoms and diagnosis (85%), depression and suicide prevention (70%), psychotropic medications and their side effects (50%), and general psychological health (45%). A smaller number asked for more biomedical or “organ” or “neurological changes” found in mental illnesses, traditional Chinese medicine approaches to mental illness, the “latest developments” in Western psychiatric medicine, how to deal with difficult personalities, and how to console patients. The majority also reported a need for support, specifically more specialist support and better access, and were worried about whether they could do a “good enough job” when they returned to their villages.

Survey of and group discussion with trainers.

Using closed and open-ended questions and group discussions, we surveyed the trainers from Jiangxi (N=15) and Hunan (N=19). The survey used a 4-point scale (nil, mild, moderate, or strong) to assess key outcomes. Ninety-seven percent of trainers moderately to strongly agreed that the goal of the initiative to rapidly introduce psychiatric knowledge was achieved; 94% moderately to strongly agreed that the curriculum was suitable in its depth and content for trainees' background; 97% observed trainees using class-learned theoretical knowledge in the clinical practice part of training; 67% reported that trainees had improved in clinical conduct, with increased awareness of issues such as consent, confidentiality, and nonjudgmental approaches. About 50% of trainers also expressed the opinion that a 2-week training course is not sufficient for serious changes.

In group discussions, the trainers additionally highlighted the points that trainees showed more interest and participated more actively as the training went on and that trainees preferred the clinical practice component over the didactic component, especially the case discussions. Trainers found it useful to interact with their front-line colleagues, and they identified the lack of formal psychiatric training in medical school and heavy stigma as major barriers in rural mental health care. Some commented that the curriculum fell short of international standards, while others said that the curriculum was not relevant enough for rural practice.

Six-Month Posttraining Evaluation

Qualitative assessment of trainees.

An evaluation team formed by faculty from a organizing university (Tsinghua) visited both the Jiangxi and Hunan sites 6 months after the training was completed. The team held group discussions with former trainees in each province (N=20). A content analysis of the notes from the group discussions revealed several themes. The originally reported posttraining sense of novelty and of the utility of psychiatry were still present, as there was a continued positive attitude toward psychiatry for a majority of trainees. Trainees reported that they were able to use the information right away when they returned to work. They thought more about psychiatric issues. Many reported improved confidence in practice as they got better at making diagnoses. Some proudly shared success stories of detecting depression and providing counseling for the first time in their careers—they “would have missed” these patients prior to training. Some reported more, and “more appropriate,” referrals to regional hospitals; one estimated an increase of 20%–30% in the 6 months after training. Many trainees reported giving more attention to suicide issues and feeling “less hesitant” in assessing this taboo area. One example is asking about pesticide storage at homes of people with suicidal risk.

Some trainees reported more communication with specialists, and they valued the connections they had made with the trainers; they used texting and telephone calls to ask for help on difficult patients. Some trainees expressed concerns about having a new working relationship with patients and worries about how asking intimate and emotion-based questions would change the nature of their relationships in the small village. Some reported that they still lacked comfort and that they wished there were powerful medications that could cure mental illness quickly, as this was an approach to medical treatment with which they felt comfortable. They recognized that there is much more to learn.

There were many specific suggestions for future training: tailor more to the specific needs of the rural physicians, use more clinical teaching, and increase the training subsidy to provide a greater incentive for continuing medical education.

Survey of trainers and regional-level psychiatrists.

The same evaluation team as above held group discussions at sites in Jiangxi and Hunan (seven trainers from each) with trainers and with psychiatrists who receive referrals from the rural physicians who received the training. A content analysis revealed several themes. Compared with the days before their training, trainees showed evidence of new knowledge in psychiatry when they referred patients. Their diagnoses and safety awareness were also noticeably better. This was generally evident in their clinical notes and telephone communications. Suicide risk assessment had also improved; one regional psychiatrist anecdotally estimated a reduction of “up to 30%” in suicide crises involving pesticides in his region after the training, an improvement he attributed to education on means restriction in the curriculum. Other trainers reported more awareness and effort by rural physicians to get patients' families involved for safety monitoring when a suicide crisis was identified.

In general, there was more communication between front-line rural physicians and specialists, as well as more referrals, with improved mental health literacy as the trainees used more knowledgeable terms in referrals and discussions and asked more pertinent questions. There were valuable specific suggestions for future training: to include more input from rural physicians, to perform a formal needs study, and to develop web sites and Internet-based information for rural physicians.

One Year After the Initiative

National organizing members, faculty from the evaluation team (from Tsinghua University), directors of training from Jiangxi and Hunan, educators from Sichuan, and international scholars (from the University of Toronto, a long-term academic partner of Tsinghua) participated in a 3-day international forum to discuss the outcome and impact of the initiative.

At the national level, the Chinese experts found that the results from Jiangxi and Hunan were representative of the overall outcomes in the other provinces. These results have demonstrated compelling reasons for the Chinese Ministries of Health and Education to develop more psychiatric training for rural physicians at the medical school level and beyond. The initiative has shed light on the entrenched systemic barriers: an absence of psychiatric education; the resultant limit on capacity to treat mental disorders and ability to prescribe psychotropic medications; poor remuneration; and the attendant fear of and low motivation to see and treat patients with mental disorders.

Regarding the curriculum, the forum experts concurred with the feedback that future training should seek more local input. They felt that it should also incorporate best practices to address stigma, increase clinically based learning, and promote more skills in communicating, identifying emotions, and building empathy, and that it should avoid the risk of overloading trainees with theoretical knowledge.

At the regional level, the initiative's success has propelled concrete efforts to secure funding for further rural physician training and establish ongoing supportive relationships between rural physicians and regional-level psychiatrists. For example, Hunan Province plans to implement continued education in psychiatry and suicide prevention for all practicing rural physicians; Jiangxi Province plans to create a database on mental health training needs and develop new standards of training for rural physicians.

Discussion

This innovative initiative to scale up rural mental health care has introduced much-needed psychiatric education for 11,000 rural physicians. From an outcome perspective, based on the classic Kirkpatrick four-level evaluation model (

16), the initiative produced meaningful positive attitude changes toward psychiatry (level 1, reactions), uptake of skills and knowledge (level 2, learning), changes in practice (level 3, behavioral changes), and some tangible health outcomes, such as those in suicide crisis intervention, rural-regional hospital relationships, and early and potential impacts on health systems (level 4, results).

Among these, attitudinal change is possibly the most welcome and meaningful; it may reflect the usefulness of the training in the daily practice of rural physicians, helping them switch from a position of fear and avoidance to that of engagement with mentally ill patients. Research has shown in general that attitudes are hard to change over a short time (

17). The initiative's positive outcome may be an indication of the trainees' genuine thirst for psychiatric training.

While largely satisfied with the training, both trainees and trainers recommended more local input and content. Research has shown that strong involvement of the target audience can improve educational outcomes (

18). Also, delivering training at nearby locations familiar to the trainees, and conducted by trainers who are available for ongoing guidance, are two other productive aspects of the initiative (

18,

19). A preference for interactive clinical teaching over didactic teaching is common in the West and is associated with superior educational and clinical outcomes; this phenomenon appears to be similar in rural China (

18,

19). Another finding is that the trainees were interested in both the “latest” Western psychiatric knowledge and traditional Chinese approaches. This bicultural awareness is the beginning of an interesting larger discussion about the cross-cultural validity of the construct and nosology of psychiatry (

20).

Suicide prevention knowledge and skills are typically areas of deficiency in most medical training (

21). The initiative's positive findings show promise for mobilizing the vast network of front-line rural physicians to combat high suicide rates in China (

15).

This study is limited by a relatively low number of study sites and informants. However, it can potentially contribute best-practice information to other national and international efforts to teach psychiatry to primary care physicians in resource-limited settings, as well as opportunities for international educational collaboration (

22). Finally, it is to be hoped that by incorporating psychiatric skills, Chinese rural physicians can change rural mental health care as profoundly as their “barefoot doctor” predecessors changed rural primary care more broadly.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Zhiyong Yang, Jiyue He, and Yin Yuan for providing valuable input for this research.