Depressive mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders.

In clinical reports, intermittent explosive disorder (by DSM-IV or research criteria) co-occurs with a variety of other axis I disorders, such as depressive (unipolar) mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders (

7,

9). Community sampling studies report odds ratios for co-occurrence of intermittent explosive disorder with other axis I disorders (

6,

25,

26,

34) that suggest that depressive and anxiety disorders are at least four times more prevalent and that substance use disorders are at least three times more prevalent in individuals with DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder. Where data are available for onset age, the disorder begins at an earlier age than do these co-occurring conditions (

6,

34). A large clinical study (

7) also reported a significantly earlier onset age for DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder than for depressive mood disorders, nonphobic anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders in subjects with both intermittent explosive disorder and the co-occurring disorder. In addition, some disorders (e.g., mood disorders, substance use disorders during intoxication and/or withdrawal) may themselves be associated with aggressive outbursts. Accordingly, intermittent explosive disorder should be diagnosed only when a sufficient number of aggressive outbursts occur to meet diagnostic criteria while the co-occurring disorder is not active.

Bipolar disorder.

A relationship between DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder and bipolar disorder has been suggested by several in the field (

13). Co-occurrence of the two disorders has been reported at nearly 60% in at least one clinical study, and aggressive episodes in some subjects with intermittent explosive disorder appear to resemble “micromanic episodes,” with manic-like affective symptoms (e.g., irritability, increased energy, and racing thoughts) occurring prior to and during aggressive episodes in 62%–99% of subjects with DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder (

13). In nearly all other published studies, the current co-occurrence of bipolar disorder is treated as exclusionary for the diagnosis of intermittent explosive disorder. The lifetime co-occurrence rate of DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder and bipolar disorder is not zero, however. In at least two published clinical studies where such data are available, the lifetime co-occurrence of these two disorders was reported to be about 10% (

6,

7). In the one study reporting data on onset age, the mean age at onset of DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder preceded that for bipolar disorder by about 5 years (

7). While this suggests delimitation of the two disorders, it may be that the presence of intermittent explosive disorder is a harbinger of the bipolar disorder to come. In the National Comorbidity Survey Replication study (

6), DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder diagnoses were not made when the course of the disorder fully overlapped with the course of bipolar I or II disorder (i.e., intermittent explosive disorder was ruled out by co-occurring bipolar disorder in 2.3% and 3.6% of cases by broad and narrow criteria, respectively). For the remainder of the cases, the rates of co-occurrence of bipolar disorder were 14.2% and 15.6% by broad and narrow criteria, respectively, with odds ratios in the same range as those reported for unipolar depressive, anxiety, and substance use disorders (odds ratios of 4.4 and 4.6 by broad and narrow criteria, respectively).

Other impulse control disorders.

In a clinical report, McElroy et al. (

13) reported that 44% of patients with DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder had a history of other impulse control disorders, with co-occurrence rates for specific disorders ranging from 0% to 19%. Data from the largest clinical survey study of DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder (

7) indicate a co-occurrence rate of 7.3%, which is not significantly greater than the rate in subjects without intermittent explosive disorder (3.9%; odds ratio=2.0, n.s.). As with bipolar disorder, the mean age at onset of intermittent explosive disorder was earlier than that for other impulse control disorders (by 10 years), suggesting that intermittent explosive disorder does not transform into another impulse control disorder. In a family history study of intermittent explosive disorder (using research criteria), familial risk of impulse control disorders in relatives of probands did not differ from that of relatives of controls, suggesting that impulse control disorders do not aggregate in families of intermittent explosive disorder probands, as would be expected if these disorders were meaningfully related. Furthermore, lifetime co-occurrence of intermittent explosive disorder with other impulse control disorders in the relatives of all probands in the study was less than 1%, which also suggests little, if any, link between intermittent explosive disorder and other impulse control disorders.

Axis II disorders.

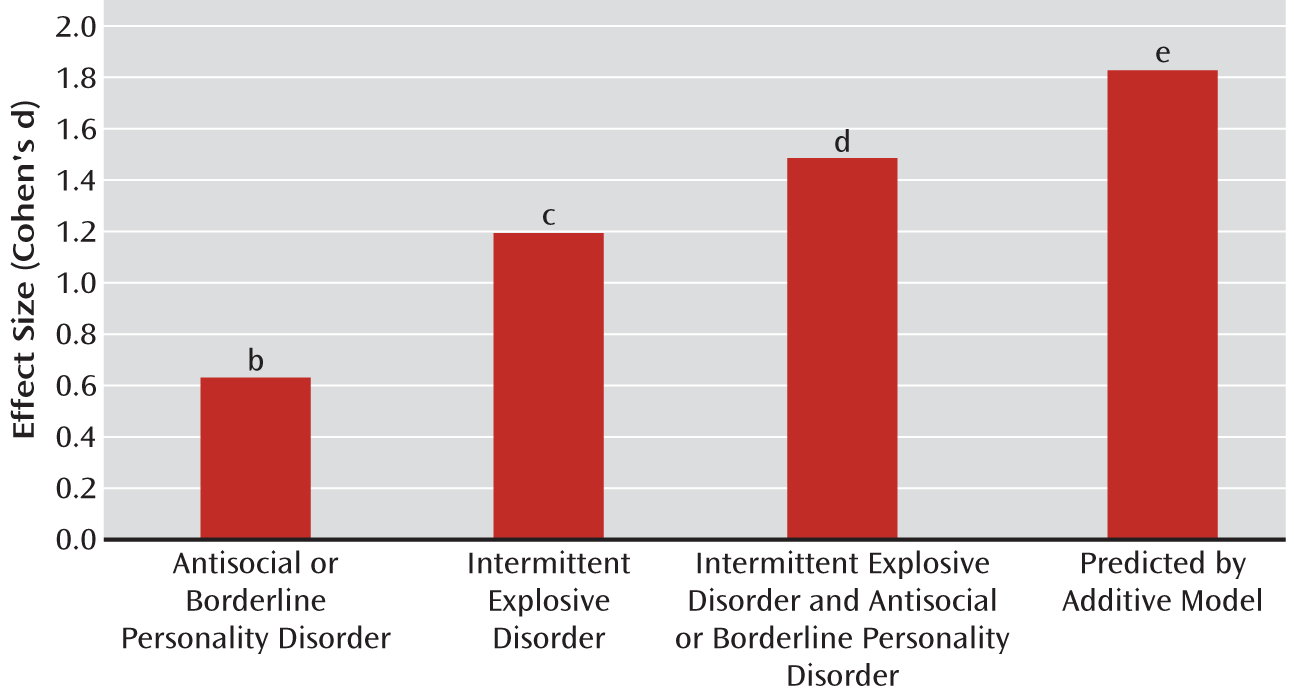

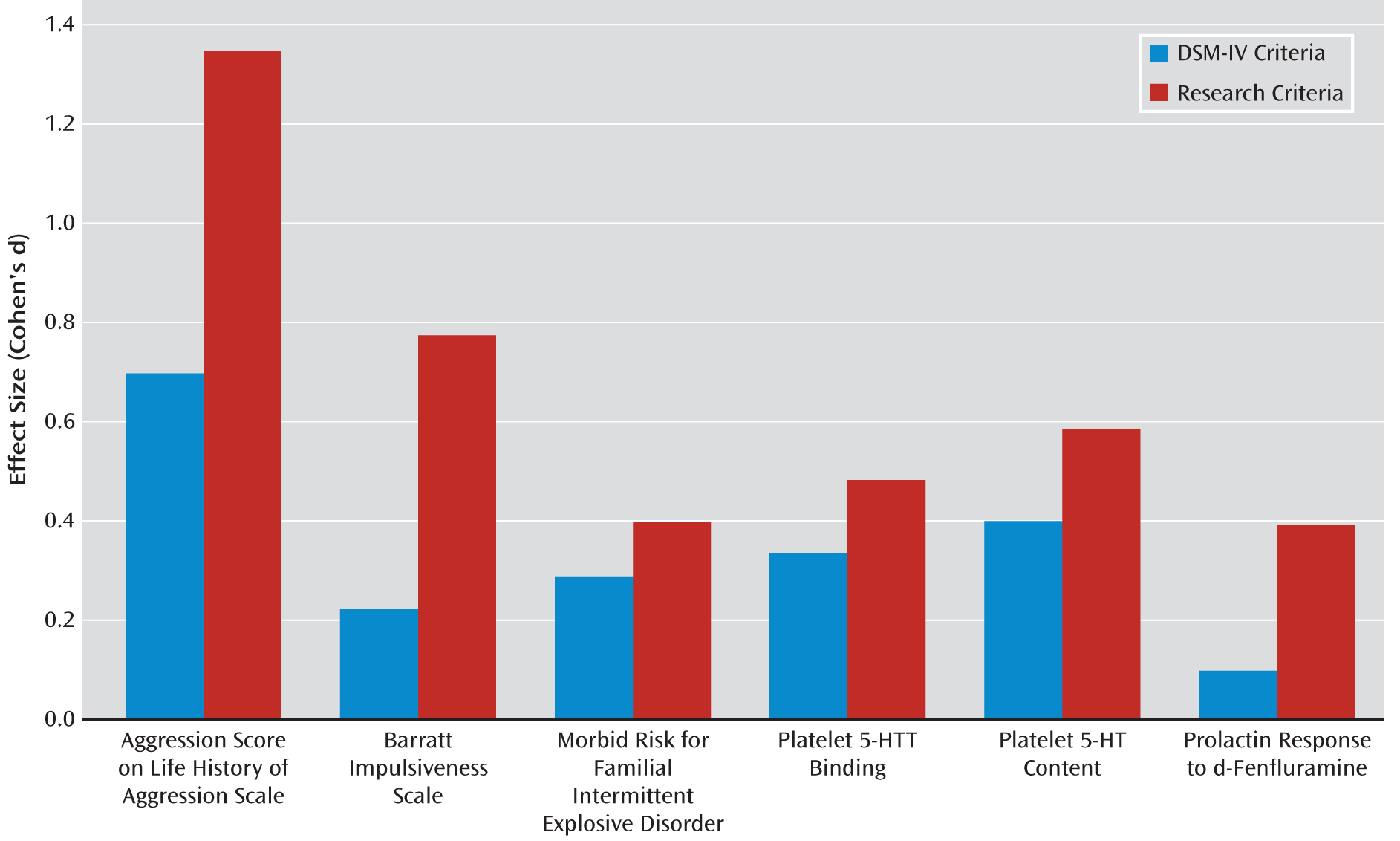

Axis II disorders have not been closely examined in community studies of intermittent explosive disorder. However, in two samples (in Philadelphia and Chicago) of psychiatric subjects with or without intermittent explosive disorder (using research criteria), our group found that only patients with comorbid antisocial and borderline personality disorders are more prevalent among subjects with intermittent explosive disorder than among those without. Odds ratios for antisocial (10.5) and borderline personality disorders (8.0) were statistically significant (p<0.001) and were similar across the two samples (E.F. Coccaro et al., unpublished 2012 data). This degree of co-occurrence may be due to higher levels of aggressive behavior in individuals with antisocial and/or borderline personality disorder. However, data from our subjects (N=1,300 combined) show that while individuals who have only antisocial and/or borderline personality disorder have higher Life History of Aggression scores than psychiatric comparison subjects (patients with axis I or II disorders who have neither intermittent explosive disorder nor antisocial or borderline personality disorder), Life History of Aggression scores among subjects who have only intermittent explosive disorder are twice as high (antisocial or borderline personality disorder compared with psychiatric comparison subjects, effect size=0.58 standard deviations; intermittent explosive disorder compared with psychiatric comparison subjects, effect size=1.15 standard deviations) (

Figure 2). Thus, having antisocial or borderline personality disorder accounts for only half of the magnitude of aggression seen in subjects who have only intermittent explosive disorder. The effect size for subjects with both intermittent explosive disorder and antisocial or borderline personality disorder was 1.43 standard deviations, significantly less (p<0.05) than that predicted by the addition of the separate effects of intermittent explosive disorder and antisocial or borderline personality disorder on aggression scores (1.73 standard deviations). Accordingly, the combined effect of intermittent explosive disorder and antisocial or borderline personality disorder on aggression scores is not greater than would be expected by adding the level of aggression attributable to antisocial or borderline personality disorder to the level of aggression attributable to intermittent explosive disorder. Multiple regression analysis of these data sets also reveals that the shared variance between intermittent explosive disorder and antisocial or borderline personality disorder is rather small at less than 10% (R

2=0.096), with antisocial personality disorder uniquely accounting for only 2.9% and borderline personality disorder for 4.0% of this variance with intermittent explosive disorder. Addition of composite aggression scores (assessment of life history of aggression and aggressive temperament) to the regression model reduced the relationship with antisocial or borderline personality disorder to statistically nonsignificant levels (<0.3% of the variance for each), suggesting that only aggressive, rather than nonaggressive, features of antisocial or borderline personality disorder have any relevance for the co-occurrence of these disorders. Also notable is the observation that rates of co-occurrence of intermittent explosive disorder (using research criteria) and antisocial or borderline personality disorder depend on the setting of ascertainment; the rate of antisocial or borderline personality disorder in subjects with intermittent explosive disorder is much smaller in community samples (25% [

24]) than in clinical research samples (85% [E.F. Coccaro et al., unpublished 2012 data]). Further support for the distinction of intermittent explosive disorder from antisocial and borderline personality disorders comes from taxonic analyses demonstrating that the latent structure of intermittent explosive disorder is categorical (

21), while those of antisocial (

35) and borderline personality disorders (

18) are dimensional.

Disruptive behavior disorders in childhood.

A critical issue for the field of psychiatry is how best to describe impulsive aggression in children or adolescents. Often these individuals are thought to have bipolar disorder, although many question this view. Additionally, the nature of the relationship between intermittent explosive disorder and disruptive behavior disorders is important because both sets of disorders begin in childhood or adolescence, and DSM-IV criteria suggest that intermittent explosive disorder should not be diagnosed in the presence of disruptive behavior disorders (note that DSM-IV actually states that the diagnosis of intermittent explosive disorder should not be given when other disorders “better explain” the clinical presentation). Examination of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication study data reveals a significant association between DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder and disruptive behavior disorders. Lifetime co-occurrence rates of intermittent explosive disorder (narrowly defined) with disruptive behavior disorders were as follows: with conduct disorder, 19.3% (odds ratio=6.4, p<0.001); with oppositional defiant disorder, 21.6% (odds ratio=6.5, p<0.001); with ADHD, 17.2% (odds ratio=6.1, p<0.001); and with all disruptive behavior disorders, 37.9% (odds ratio=7.3, p<0.001). The rates of co-occurrence for the specific disruptive behavior disorders were lower and not statistically significant when more than one disruptive disorder was present (e.g., conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder; conduct disorder and ADHD; oppositional defiant disorder and ADHD). The co-occurrence rate of intermittent explosive disorder with conduct disorder in the absence of oppositional defiant disorder was 11.0% (odds ratio=5.8), and in the absence of ADHD, 16.3% (odds ratio=6.6). The co-occurrence rate of intermittent explosive disorder with oppositional defiant disorder in the absence of conduct disorder was 13.5% (odds ratio=6.1), and in the absence of or ADHD, 16.3% (odds ratio=6.8). The co-occurrence rate of intermittent explosive disorder with ADHD in the absence of conduct disorder was 14.1% (odds ratio=6.4), and in the absence of oppositional defiant disorder, 11.6% (odds ratio=6.4). When considering onset age and recency of disorder, the time frame of intermittent explosive disorder overlaps with that of disruptive behavior disorders in only about a third of cases of a history of both disorders (11.9% compared with 37.9%). Thus, only about 12% of those with DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder would be excluded if the disorder cannot be diagnosed in the current presence of any disruptive behavior disorder.

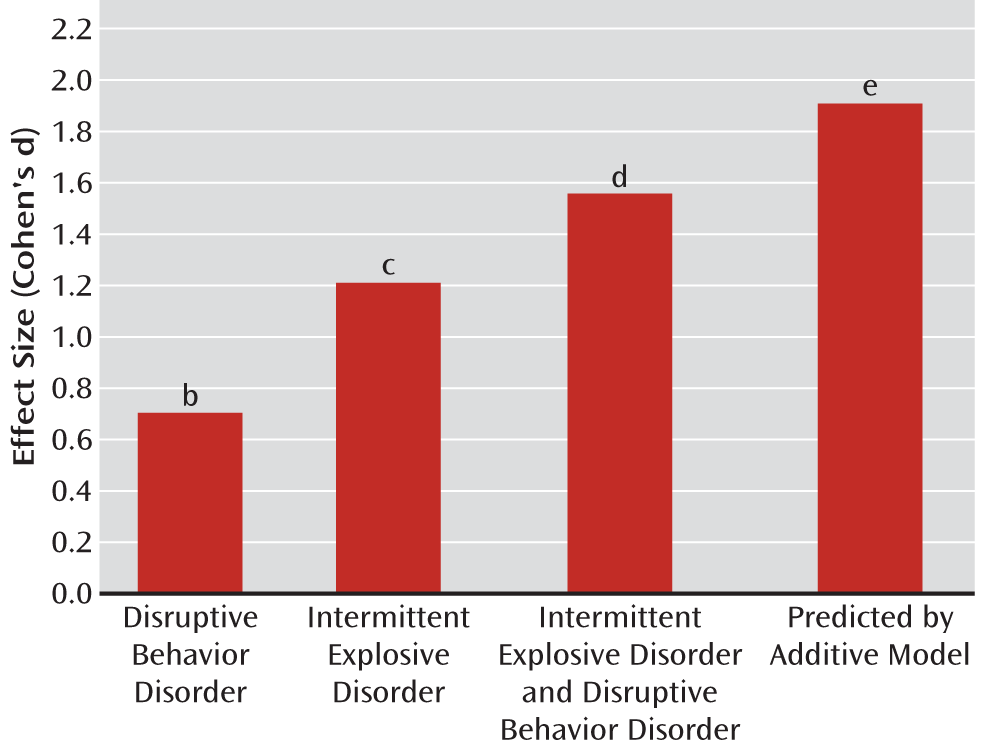

This high co-occurrence between intermittent explosive disorder and disruptive behavior disorders may be expected since some form of aggression (or impulsivity) is part of the DSM-IV criteria for each disruptive behavior disorder. Examples of predatory or premeditated aggression (e.g., robbery, extortion, sexual abuse, physical cruelty) are described in the criteria for conduct disorder. Examples of impulsive aggression are described in the criteria for oppositional defiant disorder (e.g., arguing, temper tantrums). Impulsivity (e.g., blurts out answers, interrupts others), but not aggression, is a diagnostic feature of ADHD, and impulsive behavior typically correlates with aggressive behavior. Despite these relationships, multiple regression analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication study data reveals that shared variance between DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder (narrowly defined) and history of the three disruptive behavior disorders is less than 5% (R

2=0.046), with unique variance accounting for intermittent explosive disorder at less than 1% for each disruptive behavior disorder. Accordingly, the relationships among these disorders may not be as strong, or as interdependent, as they might appear in the co-occurrence data. Moreover, when we examined the effect of a lifetime history of disruptive behavior disorder on intermittent explosive disorder (using research criteria) in our own clinical research data sets, history of a disruptive behavior disorder does not account for the levels of aggression seen in intermittent explosive disorder (

Figure 3). That is, the magnitude of the effect of a history of a disruptive behavior disorder on aggression scores (0.71 standard deviations; i.e., Life History of Aggression scores for psychiatric comparison subjects subtracted from scores for those with a disruptive behavior disorder alone) is less than the effect size for intermittent explosive disorder alone on aggression scores (1.22 standard deviations, p<0.05). While the corresponding effect size for disruptive behavior disorder history

and intermittent explosive disorder on aggression scores (1.57 standard deviations) was significantly (p<0.05) greater than that of intermittent explosive disorder, it was less than that predicted by combining the effect sizes of aggression score attributable to a history of a disruptive behavior disorder with that attributable to intermittent explosive disorder (1.57 standard deviations compared with 1.92 standard deviations, p<0.05). Accordingly, the presence of a disruptive behavior disorder history alone falls short of explaining the greater degree of aggression seen in intermittent explosive disorder with a history of a disruptive behavior disorder.

Finally, when life history of aggression is accounted for, current severity of oppositional defiant disorder or ADHD symptoms (data were not available for current conduct disorder symptoms) was found to track with history of oppositional defiant disorder or ADHD, but not intermittent explosive disorder. In this regard, individuals with intermittent explosive disorder (using research criteria) are similar to psychiatric comparison subjects, while individuals with intermittent explosive disorder and a history of a disruptive behavior disorder are similar to those with a history of a disruptive behavior disorder alone. The difference between the two groups is substantial (effect size=1.0 standard deviation) and indicates that subjects with intermittent explosive disorder (without a history of a disruptive behavior disorder) do not display the level of oppositional defiant disorder or ADHD psychopathology that would be expected if these were the same disorders by different names. Accordingly, individuals with intermittent explosive disorder and a history of a disruptive behavior disorder display the same level of oppositional defiant disorder or ADHD psychopathology as those with oppositional defiant disorder or ADHD alone because of the co-occurrence of these disruptive behavior disorders. Separation of intermittent explosive disorder from the disruptive behavior disorders is also suggested by taxometric analyses reporting that the latent structure of conduct disorder (

36), ADHD (

37), and oppositional defiant disorder (E.F. Coccaro et al., unpublished 2012 data) are dimensional while that of intermittent explosive disorder (

21) is categorical. While all these data suggest the independence of intermittent explosive disorder from the disruptive behavior disorders, confirmation of these observations must await the prospective, longitudinal study of children and adolescents in which data relevant to the criteria for intermittent explosive disorder and disruptive behavior disorders are simultaneously collected.