For many years, stress and cue reactivity have been hypothesized to play critical roles in drug addiction. Stress has been found to be a risk factor for initiation of drug abuse as well as a risk factor for relapse; a history of severe childhood stressors has been shown to be a risk factor for early onset of problem drinking in adolescence and alcohol and drug dependence in adulthood (

1), and higher anxiety and craving induced by stress have been associated with subsequent discontinuation of alcohol treatment (

2). Likewise, preclinical studies have shown that in animals trained to self-administer drugs, stressors can reinstate previously extinguished drug self-administration behavior (

3). All of these studies point to the importance of stress for initiation and maintenance of addictions.

In addition to providing support for the clinical finding that stress plays an important role in addictions, animal studies have also shown that drug-related cues can reinstate drug self-administration in abstinent animals (

3). Likewise, human studies have shown that overt drug-related cues are associated with increased craving and physiologic changes (

4) and that drug users have an attentional bias for drug-related stimuli compared to non-drug-using individuals (

5). In a recent study examining the effects of stress- and cue-induced craving on subsequent alcohol treatment outcomes, Sinha et al. (

2) found greater stress- and cue-induced alcohol craving in alcohol-dependent patients than in a comparison group. Within the alcohol-dependent patients, cue-induced anxiety and stress-induced alcohol craving were both associated with poorer treatment retention, suggesting a combined effect of stress and cue reactivity on treatment outcome.

There is a growing body of evidence that the effects of stress and cue reactivity on drug addiction may differ by gender. Although drug use disorders, drug abuse, and drug dependence are consistently more common among men than women, there is evidence that women who do become addicted to drugs have more severe clinical problems associated with drug use (

6). Some studies have shown differences in craving in response to cocaine cues between male and female cocaine users (

4). Likewise, studies have shown that female cocaine users have higher stress reactivity than their male counterparts (

7). These differences between male and female drug users have been hypothesized to be related to ovarian hormones; this relationship was reviewed by Hudson and Stamp (

8). Brain imaging studies have also shown differences between male and female substance users. As reviewed by Andersen et al. (

9), studies comparing brain responses to cue reactivity in cocaine-using males and females have shown greater cerebral blood flow in the amygdala, insula, and orbitofrontal cortex in women than in men. Other studies indicated greater brain activation in women in response to stressful imagery in the posterior cingulate, insula, and inferior frontal cortex.

The study described in the article by Potenza et al. (

10) in this issue of the

Journal is novel in its examination of the effects of stress and drug cue reactivity on brain function in male and female cocaine users and in comparison subjects who were social drinkers. The finding of the study, a three-way interaction of gender, drug use diagnosis, and stimulus (stress versus drug cue), shows the complexity of the relationship of brain function, gender, and drug dependence. Specifically, female cocaine users showed greater activation in a number of brain regions, including the amygdala, striatum, and insula, in response to stress cues and neutral cues. Within male cocaine users, the pattern of brain activation was similar but occurred in response to drug cues rather than stress cues. Differences between male and female cocaine users were also found in correlations between brain activation and subjective craving; female subjects showed positive correlations between subjective craving and brain activation in several brain regions, including the midbrain, hippocampus, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, and thalamus, whereas male subjects showed positive correlations between subjective craving and activation in the insula, in the dorsolateral, dorsomedial, temporal, and parietal cortices, and in the hippocampus.

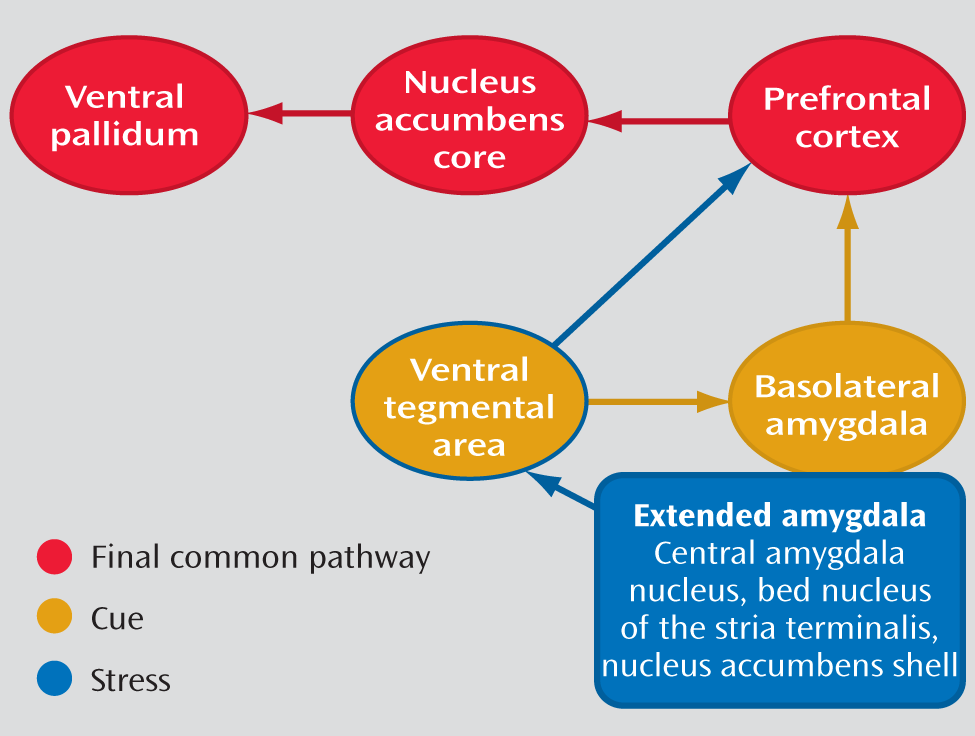

As reviewed by Koob and Volkow (

11), drug addiction is a disorder that involves elements of both impulsivity and compulsivity, which produce an addiction cycle composed of three stages: 1) binge/intoxication, 2) withdrawal/negative affect, and 3) preoccupation/anticipation. In this model of addiction, stress plays a key role in both the withdrawal/negative affect phase and the preoccupation/anticipation phase through the extended amygdala (including the central nucleus of the amygdala, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, and the nucleus accumbens shell), as shown in

Figure 1. In contrast, cue reactivity is instrumental in the preoccupation/anticipation phase through the basolateral amygdala. The findings of the study by Potenza et al. are consistent with the model of Koob and Volkow, but it appears that the role of stress mediated by the extended amygdala is greater in female drug users, whereas the role of the amygdala in cue reactivity is greater in male drug users.

These findings have potential clinical implications as well. If stress plays a greater role in brain function in addictions in female drug users, treatments targeted at stress reduction (either pharmacological or behavioral) may have greater utility in female drug users. Preclinical studies have shown that pharmacological manipulation using corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and α-noradrenergic medications alter stress-induced reinstatement of drug administration (

13). CRF antagonists block stress-induced reinstatement of drug self-administration. Likewise, α

2-noradrenergic agonists also block stress-induced drug relapse through autoreceptors that reduce noradrenergic activity. Pharmacological interventions of this type could be more effective in drug-dependent patients with higher stress reactivity, such as female patients. Likewise, behavioral therapies targeted at stress reduction, such as meditation, have been explored for addictions, and there is at least some preliminary evidence that female patients have greater reductions in anxiety and withdrawal symptoms than male patients when treated with meditation (

14). To date, the specific role of gender in addiction treatment trials has been underexplored. The findings of Potenza et al. support further research on the role of gender in treatment for addictions, and they offer some avenues for potential treatments that could be more effective in female drug-dependent patients.