Despite the fact that cocaine often captures the headlines as the villain of abused drugs, amphetamine abuse is a more prevalent problem and is reported to have a greater number of abusers than cocaine and heroin combined (

1,

2). The lack of any effective pharmacotherapies specific to stimulants remains a major impediment to combating this particular type of substance abuse. In this issue of the

Journal, a report by Tiihonen and colleagues (

3) is encouraging information indeed.

Tiihonen et al. report on an increasingly popular approach of using opiate-specific antagonists to treat other-than-opiate abuse. The use of opiate-specific antagonists, such as naloxone and naltrexone, to treat heroin abuse is well documented and has strong pharmacological backing. The use of opiate antagonists to treat different classes of drugs of abuse (e.g., alcohol, stimulants) is perhaps not intuitive but has gained strong theoretical and practical support as the general mechanisms of the biological basis of addiction become better understood (

4,

5) and numerous preclinical and human studies yield positive results in reducing alcohol (

6,

7) and amphetamine (

8,

9) intake.

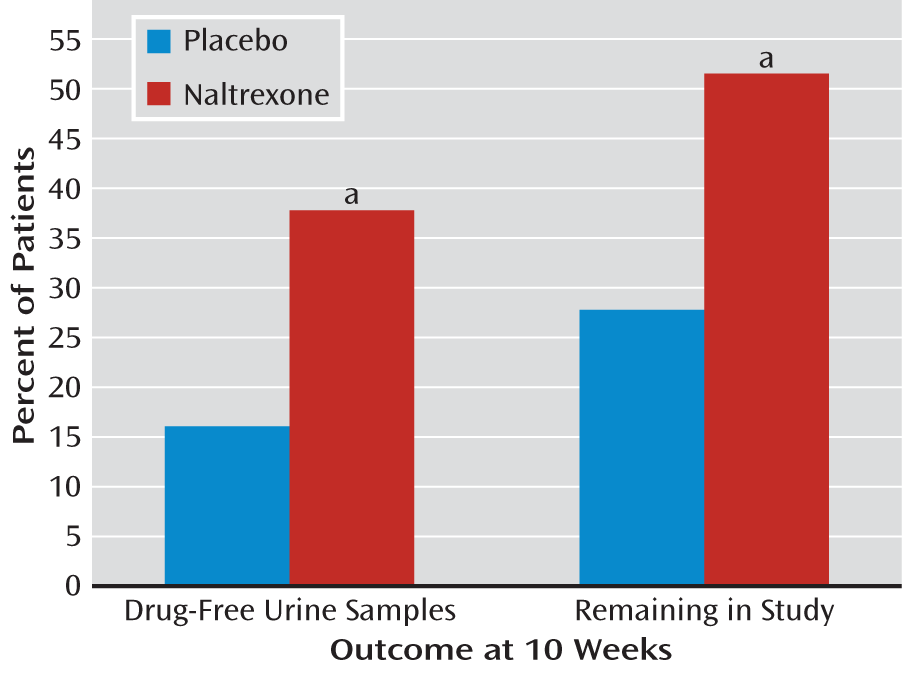

In a straightforward manner, Tiihonen and co-workers report the results of a 10-week clinical trial assessing the effects of the opiate antagonist naltrexone (in a sustained-release, implantable form) on individuals with dual dependence on heroin and amphetamine. Several important measures of effectiveness were used and reported: proportion of patients with drug-free urine samples, number of days of amphetamine use, changes in Clinical Global Impressions Scale (CGI) score, and retention rate. Additional measures included changes in the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score, adverse events, and reports of drug cravings.

The naltrexone-treated group had significantly more heroin-free urine samples at the 10-week assessment, and the difference in amphetamine-free samples approached significance. Fifty-two percent of the urine samples were heroin free versus 20% in the placebo-treated group, and 40% of the samples were amphetamine free versus 24% in the placebo-treated group. Among the patients who continued to use amphetamines, the naltrexone-treated group had fewer instances of use, although again the difference just missed statistical significance. When urine samples were analyzed for the presence of

either drug, 38% of the naltrexone-treated group were found to be drug free, compared with only 16% of the placebo-treated group (

Figure 1, left). Two clinical assessments of illness severity and treatment outcome showed that the naltrexone-treated patients had substantially more and significantly greater improvement. On the CGI, 56% showed much or very much improvement, compared with only 14% of the placebo patients, and the mean GAF scores were 82.0 for the naltrexone-treated patients and 71.9 in the placebo-treated arm. Retention in the study for 10 weeks was significantly better for the naltrexone-treated group: 52% versus 28% for the placebo implant group (

Figure 1, right side). There was not a significant medication effect on craving, with both groups overall showing decreases. Of interest, however, is that patients in the naltrexone-treated group who continued to use amphetamine reported significantly less of an amphetamine effect, indicating that naltrexone suppressed the euphoric effect more than placebo. Minor changes in liver enzymes were noted, but no difference between groups in adverse reactions were observed during the course of the study.

A strength of the study by Tiihonen et al. is the use of a long-acting, depot formulation of naltrexone. Medication compliance is an issue in many clinical studies. There are obvious advantages for using a medication that does not require the patient to take it daily. Since 2006, naltrexone has been available in an extended-release injectable formulation approved for treatment of alcohol dependence, and since 2010 it has been approved for treatment of opioid dependence. This formulation is a once-a-month gluteal muscle depot injection, whereas the medication used by Tiihonen et al. is a subcutaneous implant capable of releasing naltrexone for 8 to 10 weeks. The authors note in addition that naltrexone blood levels with the implant are somewhat higher than with the depot injection but are within a range found to be effective for treating opioid dependence (

10). Formulations that can produce therapeutically effective levels (as in this study) over 2 months have obvious advantages over shorter-acting formulations and daily dosing regimens.

The results on craving address an ongoing issue in the treatment of drug abuse. Numerous questions exist as to the contribution of drug craving (and subjective responses in general) to abuse/dependence and its involvement with relapse rates. Although it may seem intuitive that subjective cravings and drug use/relapse are related, a causal relationship has not been established. In this study, cravings overall decreased over the 10 weeks but not selectively for the naltrexone group. Jayaram-Lindström and colleagues established that naltrexone (50 mg daily) could reduce the subjective responses to amphetamine, and they showed that these reductions were related to decreases in amphetamine use over a 12-week clinical trial (

8,

11). Work by my colleagues and me showed that monthly depot injections of naltrexone attenuated blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal activation in response to alcohol cues in specific regions of the brain associated with the salience of drug-relevant cues (unpublished data). Collectively, these results indicate that naltrexone may work by means of alterations in subjective and physiological responses to drug cues. Additional work in this area is certainly needed.

The treatment of the primary drug of abuse—or in this study, of two drugs of abuse—frequently leads to the question of whether compensatory intake of other drugs will occur. Will an individual simply substitute alcohol and/or marijuana, for example, for the decrease in heroin or amphetamine? It is encouraging that this was not found to be the case in the study by Tiihonen et al., and this result is consistent with findings in other studies of this possibility (

10,

12).

It is important to point out the obvious: that pharmacotherapy—whether for opiate, stimulant, nicotine, or alcohol abuse—is effective only for a percentage of those treated. The results of Tiihonen et al. are encouraging not only for showing a direct effect of naltrexone in reducing opiate and amphetamine use but also for significantly increasing ratings of functioning and retention. Studies in the field emphasize the importance of retention over a period of many weeks and months in determining a successful outcome. Retaining patients in programs where they can obtain beneficial pharmacotherapies in conjunction with behavioral and cognitive therapies may be our most effective treatment strategy for combating the difficult medical, behavioral, and societal problem of substance abuse.